Sorry, but no, the Wright brothers did not really invent the airplane: An all too brief overview of the piloted powered heavier than air flying machines fabricated and / or tested before 17 December 1903, part 2

Good morning, afternoon or evening, my reading friend. I hope you are well. Not everyone has that chance.

Would I be correct in assuming that you are ready and eager to renew our acquaintance with the individuals who fabricated and / or tested piloted powered heavier than air flying machines before 17 December 1903? […] Wunderbar!

Let us initiate this second part of our quest more or less when we finished the first part of this mind-blowing article, in other words at the end of the 19th century, during the period known as the Belle Époque or Gilded Age, a period which was neither “belle” nor gilded for the ginormous majority of people living, surviving actually, on Earth at the time – people like my eight great grandparents for example, but I digress. Back to our pioneers of powered flight.

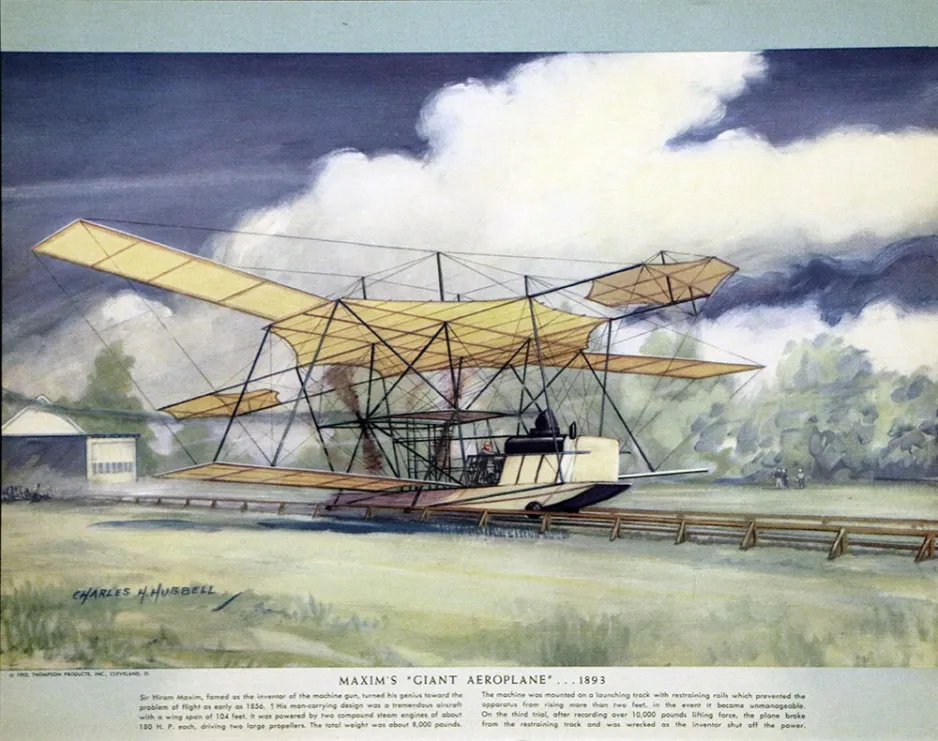

An artist’s impression of the test of Hiram Stevens Maxim’s gigantic steam-powered aeroplane, Bexley, England, 1894, painted by Charles Herman Hubbell, one of the best known American aviation artists of his day. Charles Herman Hubbell, Maxim's 'Giant Aeroplane' ... 1893 [sic]. 1952. https://hubbellaviationprints.com/

Hiram Stevens Maxim (1840-1916) was an American inventor / businessman who set up shop in England in 1881. Known around the world for the creation, in 1883-84, of the first fully automatic machine gun, one of the most murderous weapons ever imagined by a human being, he was one the first people to use a wind tunnel to test various components of the ginormous twin-engine steam-powered aeroplane he wanted to build. In 1891, at Bexley, England, after 2 or so years of work, Maxim put together a team of workers who slowly constructed said aeroplane. And no, he did not build his aerial giant. He supervised that construction work.

A brief digression if I may. An expression like pharaoh Khnum Khufu built the great pyramid has me rolling in the aisles. Just imagine that good pharaoh carrying one by one the 2 300 000 or so blocks of stone which made up that structure. Assuming he had ruled for about 45 years, Khnum Khufu would have been carrying 140 blocks a day. That herculean labour would have required a lot of magic potion, and… Magic potion? Getafix?? Asterix??? Nothing?! Really? Sigh…

And yes, Maxim designed the powerful yet remarkably light engines of that flying machine.

Maxim also supervised the construction of a 550 or so metre (1 800 or so feet) long dual track with guard rails. Yes, yes, a dual track with guard rails. You see, Maxim did not want to soar into the heavens. Nay. He only wanted to see whether or not his aerial behemoth would lift off its track.

On 31 July 1894, with Maxim putting the pedal to the metal, his aeroplane, a 3 625 or so kilogrammes (8 000 or so pounds) giant with a wingspan of almost 32 metres (about 104 feet), did just that. Indeed, it flew over a distance of slightly more than 300 metres (1 000 or so feet). At that point, one of the guard rails broke. Fearing that the other one might break as well, Maxim cut power. His aeroplane was damaged when it touched down. None of 3 people on board was injured.

Maxim demonstrated his invention in early 1895, at a safe speed of course, to raise funds for Bexley Cottage Hospital. He even took several / many male (and female?) passengers, not at the same time of course. Maxim demonstrated his aeroplane for the last time in July 1895, on one if not two separate occasions.

A passenger in late July was none other than George Frederick Ernest Albert of house Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Unable to order the Duke of York and future King George V to please step out of the aeroplane, his minder, Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Edmund Commerell, was beside himself with worry. In the end, the restrained hop went swimmingly.

To paraphrase, out of context, the title of a 1983 (!) hit song by American songwriter / singer / actress / activist Cynthia Ann Stephanie “Cyndi” Lauper, the duke just wanted to have fun.

Speaking (typing?) of fun, would you like to watch a video which showed Sir Hiram S. Maxim’s Captive Flying Machine?

And yes, Maxim designed that amusement ride which was produced in several examples of various sizes, in 1904 (and 1905?), by Sir Hiram Maxim’s Captive Flying Machines Company Limited. Would you believe that one of these rides was still us as 2024 began? It could be found at Blackpool Pleasure Beach, an amusement park located at the seaside resort town of Blackpool, England.

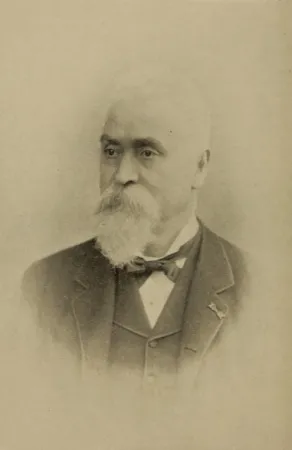

Karl Wilhelm Otto Lilienthal, circa 1896. J. Lecornu. La Navigation aérienne : Histoire documentaire et anecdotique. (Paris: Librairie Vuibert, 1913), 324.

Karl Wilhelm Otto Lilienthal (1848-96) was a German inventor / industrialist / theatre director / author / amateur actor who began, in 1891, to test a series of (up to 20 or so?) very basic gliders of his own design, at Steglitz, then in Lichterfelde, German Empire, near Berlin in both cases.

Indeed, the Normalsegelapparat he developed in 1893 was the first piloted flying machine to be put in production, in very small numbers I will admit, in 1894, by Dampfkessel- und Maschinenfabrik Otto Lilienthal of Berlin.

No later than mid-August 1894, Lilienthal tested an ornithopter he hoped to power with either a carbon dioxide engine, or his own muscles. The wing flapping mechanism of that flying machine did not prove all that successful. The latter thus proved unable to fly.

You may wish to note that what follows is very sad indeed.

Lilienthal completed a larger ornithopter in 1896. He had yet to test it when fate intervened, after more than 2 000 gliding flights. On 9 August, a glider Lilienthal was testing pitched forward and dove. Lilienthal was seriously injured in the ensuing crash. He died the following day. Lilienthal was then only 48 years old.

The first monument in memory of Lilienthal was unveiled in Steglitz in 1914. A small local history museum opened in 1927 in his hometown of Anklam, Germany, dedicated part of its space to him. The hill from which Lilienthal had flown, the Fliegeberg, at Lichterfelde, became another monument in his memory in 1932. This pioneer has been commemorated in many other ways since then. The Otto Lilienthal Museum, in Anklam, opened its doors in 1991, for example.

It might be appropriate here to mention that Lilienthal was mentioned in an August 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

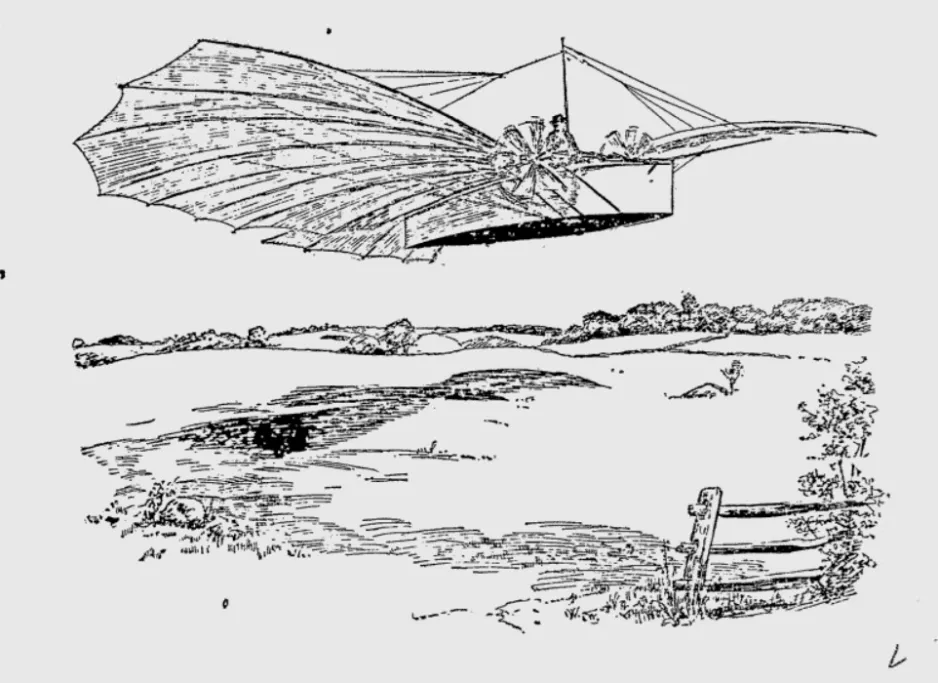

An artist’s impression of the steam-powered aeroplane designed and built by Newton Roberts Gordon in flight. Anon., “A New Flying Machine.” The Daily Telegraph, 2 October 1894, 3.

The steam-powered aeroplane designed and built by Newton Roberts Gordon on its launch ramp, Chowder Bay, near Sydney, New South Wales. J. S. Boot, “Aerial Navigation.” The Australian Town and Country, 12 January 1895, 31.

Newton Roberts Gordon (1850-1925) was a talented English Australian mechanical draughtsman / inventor who, after 7 or so years of design and work, completed an aeroplane no later than late September 1894, in Sydney, New South Wales. The steam engine of that flying machine, some sort of ornithopter, activated four somewhat large paddles which were to propel it into the skies.

Even though Gordon seemed eager to go down a short ramp on top of a cliff near Sydney, make a brief flight and alight in the water, he was nowhere to be seen, on 26 December, when his creation was put on a trolley on said ramp on top of a cliff at Chowder Bay, near Sydney.

You see, Gordon had walked away around mid-December on account of demands made upon him by one or more of his backers. As a result, he seemed to be of the opinion that any attempt to fly would end badly. (Hello, EP!)

Said backers did not walk away, however. As news of an attempt spread, more and more people became intrigued, so much so that, on the specified day, 10 to 15 000 people lined up the cliff. I kid you not. The waters off shore were also covered with boats crammed with people.

That was undoubtedly the largest crowd assembled to see an aeroplane fly until the very first significant air meet held on planet Earth, the Grande semaine d’aviation de la Champagne, held near Rheims, France, in August 1909, but back to Chowder Bay.

Minutes and more minutes passed, and nothing happened. Fueled by beer and annoyed by the heat and sun, late December being early summer in Australia, many male onlookers began to pressure the individual in charge, R.A.H. Barnet, to do something if he did not want some stoushing to occur.

And yes, stoushing is an Australianism which means brawl, fight or violence. I had to look it up in a dictionary to confirm my suspicions.

Yielding to the pressure, Barnet asked that the boats which crammed the waters of Chowder Bay be moved back so that no one would get hurt if the aeroplane alighted in the water, seemingly as planned. Many people on top of the cliff also had to move back.

With Gordon absent, however, no one seemed too eager to climb aboard the aeroplane on its maiden flight. I wonder why. Sorry, sorry. Barnet thus decided to proceed without a pilot. I kid you not.

If yours truly may quote or paraphrase the American writer publisher / lecturer / humorist / essayist / entrepreneur Mark Twain, born Samuel Langhorne Clemens, a gentleman mentioned in November 2017 and September 2022 issues of our incandescent blog / bulletin / thingee, it is no wonder that truth is stranger than fiction. Fiction has to make sense.

In any event, on the first attempt at flight, the trolley on which the aeroplane sat got stuck half way down the ramp. Once that minor issue got solved, the aeroplane was moved back to its starting point. On its second take off attempt, Gordon’s aeroplane went down the ramp and off the cliff, right onto the beach and waters below. A fire soon broke out, which destroyed the aeroplane.

There was much jeering. Some people might even have picked a souvenir or two.

Oddly enough, Gordon soon claimed that the engine of his aeroplane was not running when the latter had been launched down its ramp. His backers might not have known how to get it started, perhaps. Indeed, they might have decided to sacrifice the aeroplane rather than risk the possibility that some serious stoushing could occur, with them in the thick of it.

It should be noted that the mood of the crowd present at Chowder Bay did not improve when it realised there was not enough space on the steamships which were to bring everyone back to Sydney. Yours truly presumes that some of those ships had to return to Chowder Bay for a second pickup.

In 1907, Gordon found backers in Melbourne, Victoria, and formed the Footscray Aerial Navigation Syndicate. One or two flying machines, ornithopters perhaps, were tested, without a pilot, in May and August, by towing it or them behind an automobile. Two other attempts made in August called upon a horse to tow the aeroplane. In all cases, the flying machines stubbornly refused to fly. Faced with that series of failures, Gordon decided not to mount an engine on his creations.

And yes, my reading friend, a sizeable number of people had somehow heard about the trials held in August. Their mocking laughter did nothing to improve the mood of Gordon’s business partners.

Gordon returned to England in 1909. He constructed a gasoline powered ornithopter that same year but was unable to take off.

Gordon’s last flying machine was a human-powered ornithopter completed in 1921, the Kangartross. That name was actually a portmanteau which combined the words kangaroo and albatross, the ornithopter in question having wings like those of an albatross and legs like those of a kangaroo. The Kangartross proved unable to fly.

Charles Robert Richet (1850-1935) was a French physiologist / university professor who supervised the construction of a ginormous steam-powered and propeller-equipped ornithopter in his private domain, in the seaside resort town of Carqueiranne, France, near Toulon. Construction of that flying machine was well under way in the fall of 1896. Richet planned to launch his creation from the top of a cliff on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. And no, he would probably not be on board for that flight.

Yours truly wonders if the brain behind that flying machine might have been a French jeweller who had designed a large model aeroplane with or for Richet, a model tested at least twice at Carqueiranne in 1896-97. That gentleman was René Victor Tatin (1843-1913).

The catch with that story was that the flying machine in question was simply too ginormous. I mean, a 24 or so metre (79 or so feet) long aeroplane with a wingspan of 23 or so metres (75 or so feet)? Seriously?

And yet, a special correspondent of the European edition of a well-known American daily newspaper, The New York Herald, claimed to have seen that aerial behemoth in early October 1896.

Said behemoth never flew. It might not even have been completed for all I know.

An artist’s impression of the brief uncontrolled flight Augustus Moore Herring made at St. Joseph, Michigan, in October 1898. Karl Dienstbach, “A. M. Herring’s neue Flugversuche.” Zeitschrift für Luftschiffahrt und Physik der Atmosphäre, April 1899, 75.

Augustus Moore Herring (1867-1926) was an American engineering consultant / worker who had gained experience in aeronautics by working with the French American civil engineer / aviation pioneer Octave Chanute between December 1894 and September 1896.

Using a triplane glider he had designed and built in 1896 as a starting point, Herring completed an aeroplane powered by a compressed air engine at St. Joseph, Michigan, in the fall of 1898. In October, he piloted that biplane over a distance of slightly more than 20 metres (70 or so feet). That uncontrolled hop led to some work on new types of engines which could operate much longer. Sadly, Herring’s efforts went up in smoke when his workshop burned down during the winter of 1898-99.

Interestingly, Herring later joined forces with a gentleman we have met several / many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since October 2018, the American bicycle and motorcycle racing pilot / engine maker, Glenn Hammond Curtiss, to form Herring-Curtiss Company, in the spring of 1909. That meeting of minds did not work too well, however, and neither did the one which led to the birth of another short-lived aeroplane manufacturing firm, Herring-Burgess Company, formed in the later winter of 1909-10 by Herring and the American naval architect / yacht designer William Starling Burgess. By the looks of it, that firm only made 2 or 3 aeroplanes. Herring-Curtiss might have made 10 or so.

And yes, Herring was mentioned in a September 2020 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, and…

Err, do you have a question, my reading friend? Where did I find a publication as obscure as Zeitschrift für Luftschiffahrt und Physik der Atmosphäre? In the fantabulastic library of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, of course. It was also there that yours truly found many of the photographs and drawings used in the fabulous article you are perusing at the moment.

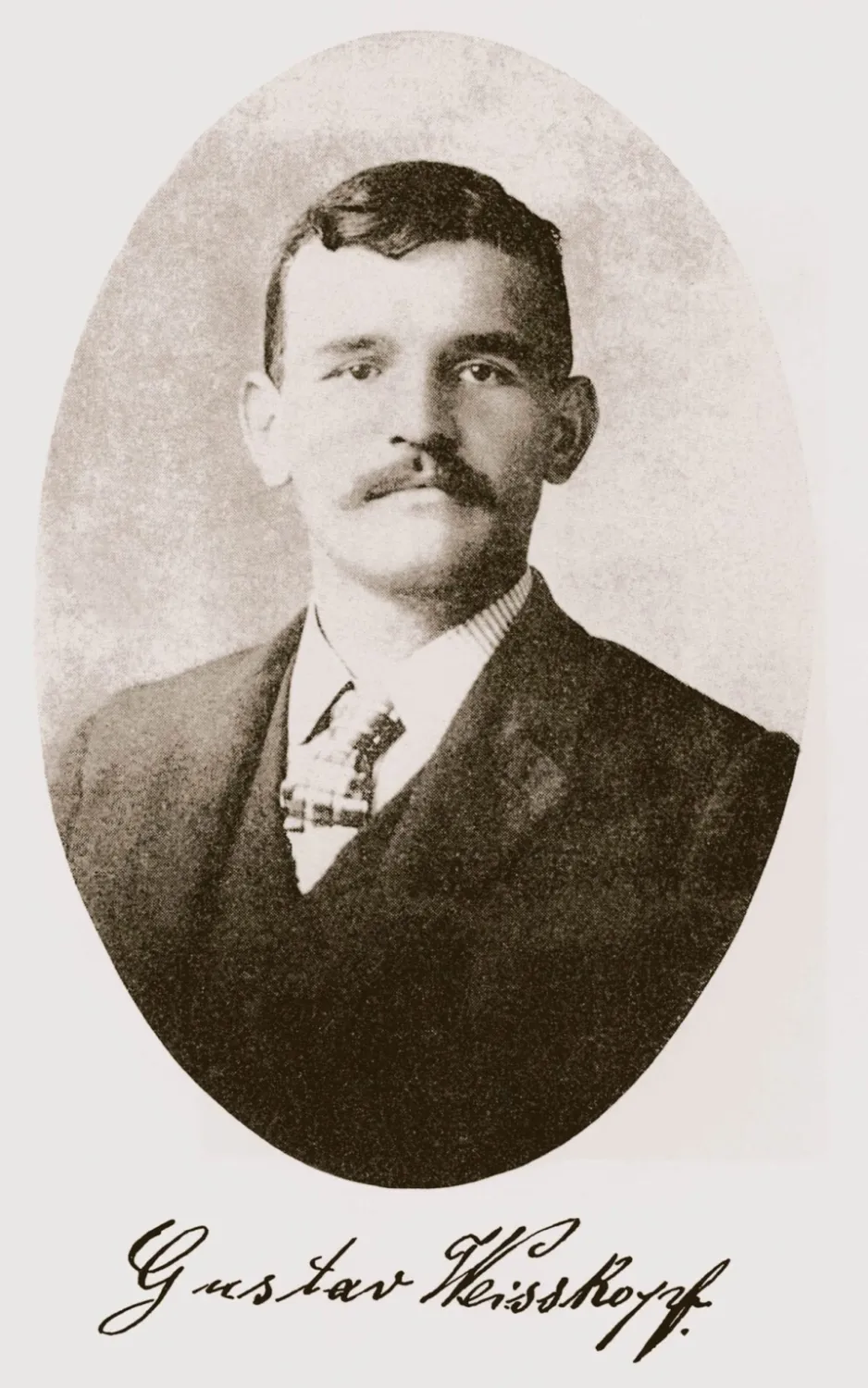

Gustave Albin Whitehead, circa 1903. Stella Randolph, Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead. (Washington: Places, 1937), frontispiece.

Gustave Albin “Gus” Whitehead (1874-1927), born Gustav Albin Weißkopf, was a German American watchman / kite pilot / mechanic who began to construct a twin-engine aeroplane fuelled with liquid air during the summer of 1899, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. That two-seat monoplane was ready to fly no later than early December. A test flight was cancelled at that time because of bad weather. That aeroplane seemingly did not fly.

Whitehead moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut, at some point in the spring of 1900. In November of that final year of the 19th century, he began to construct another aeroplane. Whitehead tested that twin-engine two-seat roadable aeroplane / flying automobile in early May 1901.

Yes, yes, you read correctly, my reading friend. A roadable aeroplane / flying automobile. The very first one in on our big blue marble in all likelihood. You see, while one of the (steam?) engines of that monoplane drove a pair of propellers, the other drove 2 of its 4 wheels.

Indeed, Whitehead and a passenger, one of his 2 financial backers and helpers, Andrew Cellie, perhaps born Andreas Zülli, drove from Bridgeport to Fairfield, Connecticut, where the first flight was to take place.

The two men then left the vehicle. On the crest of a hill, in the middle of the road, Whitehead restarted the engine which drove the wheels, and stood back. Whether or not he also started the engine which drove the propellers is unclear.

Even though it carried 100 or so kilogrammes (220 or so pounds) of ballast, the unpiloted aeroplane took off and covered a distance of 200 or so metres (660 or so feet), or so claimed Whitehead. During its second flight, the aeroplane covered a distance of 800 or so metres (2 650 or so feet) before running into a tree as it was coming down, or so claimed Whitehead. Neither claim held / holds water.

Gustave Albin Whitehead with his Whitehead No. 21 steam-powered and acetylene-fuelled aeroplane, Connecticut. Anon., “W.G. [sic] Whitehead’s New Machine.” The Aëronautical World, 1 December 1902, 99.

A slightly outlandish artist’s impression of Gustave Albin Whitehead’s steam-powered Whitehead No. 21 aeroplane in flight, Fairfield, Connecticut. Anon., “Flying.” Bridgeport Herald, 18 August 1901, 5.

On 14 August 1901, Whitehead was back in Fairfield with an aeroplane. The description of that steam-powered and acetylene-fuelled Whitehead No. 21 monoplane being identical to that of the flying machine allegedly tested in May, yours truly wonders if it might have been that very contraption, or an all but identical copy thereof. In any event, Whitehead took off and covered a distance of 800 or so metres (2 650 or so feet), or so he claimed. That claim did not / does not hold water either.

Interestingly, Whitehead stated no later than November 1901 that he would soon begin to sell examples of his flying machine to anyone who had the US $ 2 000 he was planning to ask for them. That sum corresponds to approximately $ 100 000 in 2024 Canadian currency. Those aeroplanes able to carry 6 people would hit the shelves in the middle of 1902.

But wait, there was more.

On 17 January 1902, Whitehead was back in Fairfield with yet another aeroplane, the Whitehead No. 22 monoplane. Aboard that similar looking yet far more powerful machine, Whitehead covered distances of 3.25 or so kilometres (2 or so miles) and 11.25 or so kilometres (7 or so miles), or so he claimed. He alighted on water, as planned, for at least one of those truly astonishing flights.

There was, however, a catch. Neither claim held / holds water. Worse still, the No. 22 never existed, and…

Do you have a question, my ever curious reading friend? Might the aeroplane completed in Pittsburgh and the No. 21 monoplane have been one and the same, you ask? A good question. I wish I knew.

Why did Whitehead want to go to St. Louis, you ask? A good question. You see, one of the many attractions of the world fair, besides the Games of the III Olympiad, was an aeronautical competition with a grand prize of no less than US $ 100 000. To earn this truly titanic sum of money, which corresponds to about 4 750 000 $ in 2024 Canadian currency, a pilot only needed to go around a 16-kilometre (10 miles) circuit 3 times. Easy peasey.

Gustave Albin Whitehead abord an aeroplane completed in 1903, unless that machine was simply the Whitehead No. 21 aeroplane after some more or less minor surgery, Connecticut. The machine’s propellers had yet to be installed. Anon., “Gustave Whitehead’s New Machine.” The Aëronautical World, 1 May 1903, 225.

Whitehead had yet another aeroplane all but ready for flight no later than April 1903. That triplane was fitted / was to be fitted with a gasoline engine Whitehead had designed himself, or so he claimed. Oddly enough, the often quite voluble inventor did not claim that this new machine had made some spectacular flight, besides a 105 or so metre (350 or so feet) test flight.

And yes, my reading friend, yours truly does wonder if the 1903 triplane was a really a new machine or merely a tweaked No. 21.

More interestingly perhaps, more tellingly too perhaps, no later than June 1903, Whitehead was testing a very basic triplane glider which he planned to fit with a small kerosene engine. The triplane glider in question was the 1903 triplane devoid of its fuselage.

And yes, several photographs show the 1903 glider aloft with a pilot. Those images are the only pre December 1903 photographs known to yours truly which showed a Whitehead flying machine aloft.

A person with a negative turn of mind, not yours truly of course, might wonder if, given the truly earth shaking flights made in 1901-02, some of Whitehead’s contemporaries wondered why he did not go head to head with the Wright brothers. Just sayin’.

By the way, Whitehead did not attend the Louisiana Purchase Exposition with one of his aeroplanes. He did, however, display a gasoline engine there. Indeed, Whitehead produced several aeroplane engines he sold during the 1900s. Several of these might have been made by Whitehead Motor Works (Incorporated?), a (short-lived?) firm founded in 1908 by Whitehead and a little known American aviation enthusiast, George A. Lawrence.

Would you believe that one or more of these engines were sold to Stanley Yale Beach, an American aviation pioneer who happened to be the aeronautic editor of the famous American weekly magazine Scientific American? Indeed, Beach was Whitehead’s main source of moolah during the second half of the 1900s.

The biplane that Whitehead designed and built for Beach was ready to fly in April 1909 but proved unable to fly. Beach was understandably displeased. Whitehead claimed that his partner withheld payments due to him. Beach, on the other hand, claimed that his partner was in breach of contract. Things got so bad between the two men that Whitehead spent a few brief period in jail. He had to turn a valuable engine over to Beach in order to get out.

In the spring of 1910, Whitehead began to work on a helicopter fitted with 60 rotors and 60 propellers (?!) powered by a pair of gasoline engines. If trials proved successful, that flying machine would be fitted with no less than 8 gasoline engines. Said machine was built for and financed by Lee Spear Burridge, an American typewriter industrialist / inventor who happened to be the founding president of the Aeronautical Society of America.

Why a helicopter, you ask, my reading friend? Would you believe that Whitehead had come to believe that the aeroplane was an impractical form of aerial locomotion? After all, it needed terrains long enough to take off and land. The helicopter, on the other hand, could take off and land virtually anywhere.

As you may have guessed, the trials of the Whitehead helicopter proved unsuccessful. An understandably displeased Burridge sued Whitehead to get some of his money back. The Connecticut Superior Court found in his favour, in May 1912.

In the late summer or early fall of 1910, Whitehead completed some sort of powered flying machine for Charles Jesse “Buffalo” Jones. Rather than fixed wings, that machine perhaps designed by that famous and wealthy if aging American game warden (Yellowstone National Park – 1902-05) / rancher / hunter / farmer / conservationist, used parachute-like surfaces to create the lift required when taking off, something it quickly proved unable to do. Yours truly wonders if that machine was some sort of ornithopter.

This, of course, did not mean that Whitehead had put aside his dreams of flight. Nay. He completed a far more conventional monoplane in early 1910 but was lucky to survive a crash, into the side of a bridge, in mid July, when he was ejected out of his creation without suffering any serious injury.

Whitehead was all but forgotten until the early 1930s when two Americans, educator / journalist Stella Randolph and amateur aviation historian Harvey Phillips, began to look into his story. The former published Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead in 1937. Her second book, The Story of Gustave Whitehead – Before the Wrights Flew, came out in 1966. Randolph collaborated with William J. O’Dwyer, a retired officer in the Air Force Reserve of the United States Air Force and amateur historian, to produce a third work, History by Contract, published in 1978.

In August 1964, Whithead was proclaimed Father of Connecticut Aviation by the Governor of that state, John Noel Dempsey. A headstone was dedicated on his grave site, in Bridgeport, that same month. Both of those efforts had been launched by the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association and endorsed by the state’s Department of Aeronautics.

The Deutsche Flugpioniermuseum Gustav Weißkopf opened its doors in Whitehead’s homecity of Leutershausen, West Germany, in 1974. A thorough revamp begun around 2018 culminated in September 2023 with the opening of what had become the Gustav Weisskopf Museum Pioniere der Lüfte.

You may be intrigued to hear (read?) that, around 1985, a small team of American aeronautical engineers set out to design a (slightly?) modified flying replica / reproduction of Whitehead’s No. 21 aeroplane fitted with a pair of modern engines and propellers.

None other than the American movie and television actor Clifford Parker “Cliff” Robertson III was at the controls when, in July 1986, the as yet un-engined replica rose many centimetres (several inches) from the flatbed trailer it was tethered to as the latter was towed on a runway of Sikorsky Memorial Airport, near Stratford, Connecticut.

In late December, Andrew Kosch, an ultralight aircraft pilot and biology teacher at Westhill High School in Stamford, Connecticut, took off and landed 20 times in one day. One of those (uncontrolled?) hops covered a distance of 100 or so metres (330 or so feet). As of early 2024, that replica was on display at the Connecticut Air and Space Center, at Sikorsky Memorial Airport.

A second, rather modified flying replica / reproduction of Whitehead’s No. 21, also fitted with a pair of modern engines and propellers, was completed in Germany in early 1998. That aeroplane covered a distance of 430 or so metres (1 400 or so feet) in February 1998. As of early 2024, that replica was on display at the Gustav Weisskopf Museum Pioniere der Lüfte.

In June 2013, the Connecticut General Assembly passed a bill stating that Whitehead had flown in 1901, more than 2 years before the Wright brothers. The mind boggles. Let us move on before my little poor noggin explodes.

Oh, and before my little old brain forgets, Whitehead was mentioned in a November 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

See ya later, my reading friend.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)