A blaze in the northern skies and a cinder of sidereal fire: The Bacubirito meteorite

Hail, my reading friend, full of smarts. Did you know that right until the late 1700s, if not the early 1800s, virtually all members of Europe’s scientific elite consistently mocked the illiterate peasants who claimed they had seen rocks falling from the sky?

I mean, peasants of 1800, what did they know? What could one possibly learn from observation? Had they consulted the 2 100-year-old treatises of the great Greek philosopher and polymath Aristotélēs, a smart guy who did not waste his time observing, they would have learned that rocks cannot fall from the sky. Period. Observation? Humbug. One might as well state that women deserve to have the same rights as men, or that vaccines are not part of a plot to enslave humanity.

The Ferris wheel of science began to turn on 6 Floréal of the year XI when a few thousand stones fell from the sky in the region of L’Aigle, France. Informed of that news, the government of the French Republic sent a young engineer and professor of mathematics to the scene. Jean-Baptiste Biot submitted a report on 29 Messidor in which he confirmed the presence of stones falling from the sky, a fall confirmed by testimonies collected in more than twenty surrounding villages. The Académie des sciences, in Paris, took note of said report and had to face the facts. Aristotélēs was out to lunch.

Speaking (typing?) of being out, would you believe that a few people might still be searching the ground in the L’Aigle region for small meteorite fragments which have escaped the attention of humans hot on their tracks? But I digress. Let us resume our story with...

Uh, you seem very perplexed, my reading friend. The words floréal and messidor mean nothing to you? You suffer from a mild case of culturae defectus. Nothing too serious. Floréal and messidor were the 8th and 10th months of the French republican or revolutionary calendar, introduced in September 1792 and abolished in December 1805. Allow me to convert the dates mentioned above:

6 Floréal of year XI = 26 April 1803 – an auspicious day if yours truly may say (type?) so

29 Messidor year XI = 18 July 1803

But back to our story.

Yours truly would like to chat with you today about another stone which fell from the sky. Said stone, however, did not disintegrate during its mad dash through our atmosphere. Nay. It crashed at an undetermined moment, thousands of years ago, some Mexican researchers believe, in a high valley in northwestern Mexico. These same researchers believe that a sister / brother fragment of the meteorite might have fallen off the west coast of Mexico, in the Gulf of California / Sea of Cortés possibly. At the time of its discovery, said meteorite was near a wagon road, not far from an old mining town, Bacubirito, Sinaloa.

The aerolite was discovered by accident, in 1863, by peasants working in the fields or, perhaps, by an increasingly annoyed peasant by the name of Francisco López, whose plough kept running into something big and hard underground.

This being said (typed?), the author of the article from which yours truly extracted the engraving which adorned this article, a certain N. Rosst, affirmed that this discovery only took place in 1871 when the plow of a peasant, Crescensio Aguilar, hit a hard object. Initially a tad annoyed, maybe, he wondered if he had in fact hit a silver vein. Lucky hit! His hopes were quickly dashed, however. The peasant discovered that he had hit an enormous mass of iron. He detached small pieces which were distributed to various people. This done, said people and peasant resumed their usual routine.

And yes, the name of a third resident of the Bacubirito area has been put forward. According to some, a peasant by the name of Lorenzo Aguilar discovered the aerolite at some point.

Incidentally, a few articles which appeared in 1902 in American daily newspapers also mentioned 1871 as the annus mirabilis. Worse still, a text panel which was near the meteorite, displayed on the esplanade of the Centro de Ciencias de Sinaloa, in Culiacán Rosales, Sinaloa, at the beginning of the 21st century, stated that it had been discovered in… 1874. Yours truly does not know what to think.

Before I forget, did you know that the iron used by various peoples of the Earth before the start of the Iron Age, that is before the year 3 200 before the current era, came from meteorites? Yes, yes, meteorites. Just think of the parts of a dagger, the bracelet and the headrest which were among the more than 3 300 years old treasures discovered in Egypt, in the tomb of the pharaoh Nebkheperure Tutankhamun. Yes, yes, treasures. At that time, in Bronze Age Egypt, iron was rarer and, therefore, more valuable than gold.

Closer to us, both geographically and chronologically, the Inuit and, before them, the Dorsets had been using respectively since the 12th and 8th centuries iron detached from fragments of the huge Innaanganeq / Cape York meteorite, which fell in the region of Meteorite Island, Greenland. Would you believe that iron dagger blades as well as spear and arrow heads have been discovered in several / many archaeological sites in Greenland and the Canadian Arctic?

Incidentally, do you think American explorer Robert Edwin Peary mentioned to local Inuit communities, in the fall of 1897, that he was carting away a 31 metric tonnes (30.5 imperial tons / 34 American tons) fragment of the meteorite they had been using as a source of metal for centuries? Did he even ask if they minded? Are you kidding? Are you that naïve? But back to our story.

In 1875, the Sociedad Mexicana de Historia Natural of Ciudad de México, Mexico, received a photograph of the Bacubirito meteorite, then known informally as the Sinaloa meteorite. It also received some fragments of the aerolite. A prominent Mexican mining engineer, Mariano Santiago de Jesús de la Bárcena y Ramos, then began to study said fragments. His mentor, an eminent Mexican mining engineer known worldwide, the founding director of the Instituto Geológico de México, in Ciudad de México, Antonio del Castillo Patiño, also appeared to study the fragments.

De la Bárcena y Ramos published an article on Mexican meteorites in the 1876 volume of Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences, the official publication of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, in… Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the oldest (1812) natural science research institution and museum in the Americas and an institution mentioned in a May 2022 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. The Bacubirito meteorite being poorly known at the time, de la Bárcena y Ramos only devoted about ten lines to it.

A few rare newspaper articles appeared in the United States in 1888. The governor of Sinaloa, the surveying engineer Mariano Martinez de Castro Vega, I think, had sent at that time some information concerning the Bacubirito meteorite. Presumably he had gotten it from del Castillo Patiño and / or de la Bárcena y Ramos.

The meteorite was almost entirely covered with earth, it was stated. Its mottled outer surface was slightly corroded. The aerolite was approximately 3 metres long, 2 metres wide and 1.5 metre high (just under 10 feet long, just over 6 feet 6 inches wide and almost 5 feet high). It might weigh, it was believed, nearly 32 metric tonnes (about 31 imperial tons / 35 American tons). Its general shape was reminiscent of a duck. Yes, yes, a duck.

This being said (typed?), it was perhaps in 1892 that the contemporary period of the history of our aerolite, the largest meteorite known at the time, really began. Many articles in fact appeared from October 1892 in American and British daily newspapers.

Organisers of the World’s Columbian Exposition to be held in Chicago, Illinois, between May and October 1893, might have attempted to borrow the aerolite in order to display it. Those attempts failed. Those people, however, managed to obtain permission to make a cast of the meteorite. Yours truly has been unable to confirm its presence at the exhibition site, however, assuming the cast was done of course. The World’s Columbian Exposition commemorated, perhaps a tad belatedly, the discovery of America by Christoforo Colombo, in October 1492.

The failure of the negotiations apparently stemmed from the fact that the government led by Mexican president / dictator José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori was uncomfortable with the idea of letting go even temporarily of the unique object that the aerolite was. There was a certain irony in that given the fact that a good part of the economy of Mexico was then in the hands of the “yanquis,” thanks to the laissez-faire of said dictator.

Yours truly must admit to feeling some discomfort at the idea of commemorating Colombo, a man who showed real brutality towards the indigenous populations that he met on the American continent between 1492 and 1504.

Let us not forget that the wealth of settler states like the United States and Canada was built (and is still being built?) on the backs of indigenous populations stripped of their heritage and lands, and too often decimated, by law, force of arms or disease. There is not much that is joyful about the legacy of Colombus / Colombo.

And no, there is nothing wrong with rewriting history when it comes to righting a grave injustice. White lives are not the only ones that matter, but back to our topic of the week.

Before I forget, the Bacubirito meteorite was part of the collections of the Instituto Geológico de México no later than 1911, even though it remained at its impact site. Mind you, it might very well have been incorporated into that collection in earlier years, as the institute was founded in 1888.

A new phase in the history of our aerolite began in 1902. The Christopher Columbus of the Gilded Age in question was named Henry Augustus Ward. He was an American naturalist, explorer and adventurer with a strong interest in geology and mineralogy. Indeed, during the 1850s, when he was at the most 25 or 26 years old, Ward traveled in Europe and Africa in order to unearth interesting geological and mineralogical specimens. And yes, his hobby, his passion, was meteorites.

Ward taught natural sciences (geology and zoology?) at the University of Rochester, in… Rochester, New York, between 1860 and 1862. He then left that job to create a cabinet of curiosities / collection known, in 1875 at the latest, under the name of Natural Science Establishment. The latter soon became famous for its natural history specimens sold for educational purposes, specimens ranging from the reproduction of a tiny mollusk to the skull of an elephant, specimens which included skeletons, rocks, minerals, reproductions of fossils, fossils, stuffed animals and so on.

Mind you, many of the specimens at the Natural Science Establishment were on display at exhibits of varying size. Let us mention as an example the International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and Products of the Soil and Mine, the first universal exhibition on North American soil, which was held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from May to November 1876. Said exhibition commemorated the centennial of the signing of the United States Declaration of Independence, formally The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America, in July 1776.

And yes, slavery was entirely legal in those United States in 1776, and that despite a few words at the very beginning of said declaration, namely “all men are created equal,” words which left out half the white population anyway, but I digress.

Speaking (typing?) of stuffed animals, around 1875-76, at least two employees of the Natural Science Establishment stuffed the skin of the famous circus elephant Jumbo, killed by a locomotive in Saint Thomas, Ontario, in September 1885.

Incidentally, Ward’s Natural Science Establishment Incorporated may, I repeat may, still exist in one form or another in 2023. An American firm, KDI Corporation, acquired what was by then a modern school supply house in April 1970, but back to Ward and his meteoritic / extraterrestrial hobby.

In 1897, Ward’s wealthy spouse, Lydia Ward, born Lydia Avery, teamed up with a famous and wealthy American mineral collector, Clarence Sweet Bement, to purchase a fine collection of meteorites. Shortly after that purchase, however, Ward’s stepson from his spouse’s first marriage, Avery Coonley, bought out Bement’s share. From then on, Ward began to create an important collection of meteorites, the Ward-Coonley collection, which had around 425 specimens in 1900.

In April 1901, Ward signed an agreement with the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, New York, through which the latter agreed to display a (good?) part of the collection. Said agreement also offered the museum a purchase option with first right of refusal. An interesting detail, if only for me: Ward apparently had to pay the transport costs and organise the showcases himself.

According to some, Ward was then one of the greatest collectors of meteorites in the world.

In 1912, after long fruitless discussions with at least two museal organisations and a few years after Ward’s death, in July 1906, at the age of 72, his widow sold the Ward-Coonley collection to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois, where it still is, but back to the Bacubirito meteorite.

Intrigued by what he had read and heard about that aerolite, Ward decided in 1902 to go to Mexico to examine it firsthand. In fact, it seemed that it was he who introduced the year 1871 as being that of the discovery of the meteorite. Indeed, the account told in 1903 by the aforementioned Rosst derived for a good part from an article Ward had published in 1902, but I digress.

Having obtained letters of introduction intended for the governor and director of mines in Sinaloa, courtesy of the kind director of the Instituto Geológico de México, José Guadalupe Aguilera Serrano, Ward and a small team seemingly travelled overland, through the American Cordillera, from Ciudad de México to the port city of Manzanillo, Mexico. The group then embarked on a ship going north. It disembarked at some point near the capital of Sinaloa, Culiacán, and got there on horseback – or did it use mules? Anyway, Ward and his team, reinforced by an American photographer, then began a journey of more than 160 kilometres (100 miles) – presumably on horseback, or did they use mules?

In any event, again, the team found the aerolite in a cornfield, in a hamlet (or farm?) known as Ranchito. Only a fraction was visible. As his team could not excavate the enormous aerolite alone, Ward hired thirty or so local peasants. These dug into the ground over an area of approximately 9 metres by 9 metres (30 feet by 30 feet). Much of the meteorite lied more than 1.2 metres (4 feet) below the surface of the ground. After 2 or 3 days of hard work, the entire aerolite was cleared. Only a small column of rock held it in place. Wishing to better see the ground under the meteorite, Ward asked the peasants to rotate it by attacking the small column of rock with iron bars.

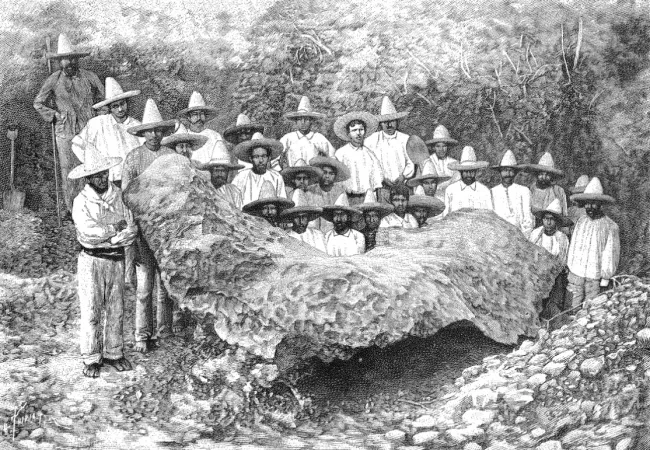

The Mexican peasants were stunned by the size of the object they had unearthed. They were equally stunned by the gullibility of those Americans who believed that such a mass of iron had fallen from the sky. A lot of American, British, Canadian, French, German, Italian or Russian peasants who, like their Mexican counterparts, had not themselves seen a boulder fall from the sky, would have been equally incredulous. And yes, these were the Mexican peasants who were / are in the engraving which was at the very beginning of this article. Said engraving was of course derived from a photograph.

According to Ward, the Bacubirito meteorite was approximately 4 metres long, 1.9 metre wide and 1.6 metre high (approximately 13 feet long, 6 feet 2 inches wide and 5 feet 4 inches high). It might weigh, he thought, about 45 metric tonnes (about 44.5 imperial tons / 50 American tons). Its general shape was reminiscent of the rising branch of an enormous jawbone.

Mind you, some people recently suggested that the aerolite looked like a gigantic ear.

Do you see the rising branch of a huge jawbone, a huge ear or a huge duck? Henry Augustus Ward almost seemed to ask himself that question, not far from Bacubirito, Mexico, 1902. N. Rosst, “La grande météorite de ‘Bacubirito’ (Mexique).” La Nature, 14 February, 1903, 172.

One wonders if the meteorite was reburied before the departure of Ward and his team.

By the way, a young researcher from the Instituto Geológico de México, Ernesto Angermann, might, I repeat might, have traveled to Bacubirito in 1903 to examine the aerolite.

That same year, the famous German mineralogist, petrologist and university professor Emil Wilhelm Cohen published an article on two Mexican meteorites, including the one located near Bacubirito, named there the Ranchito meteorite. Said text was published in Mitteilungen aus dem Naturwissenschaftlichen Verein für Neu-Vorpommern und Rügen in Greifswald and… You have no idea of what this title means, do you, my reading friend? Do not worry. I was just as baffled as you were. A translation of the title of that German periodical reads notices / communications of the association of natural sciences for New Western Pomerania and Rügen in Greifswald.

The famous Austro-Hungarian mineralogist Aristides Brezina, curator of the meteorite collection of the Naturhistorische Museum, in Vienna, Austria-Hungary, one of the oldest and most important in the world, also published during the 1900s some text which mentioned our aerolite.

The same went for the famous German mineralogist, petrographer and university professor Ernst Anton Wülfing.

In any event, an article by Ward appeared in a September 1902 issue of the American weekly Nature. And yes, it is indeed the article that yours truly mentioned a few minutes ago. Several American and foreign dailies, including some Canadian / Québec dailies, all of them anglophones, were quick to quote excerpts.

Indeed, meteorites fascinated a (large?) segment of the public. Just think of those on display at the United States National Museum, now the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, District of Columbia, no later than 1916. And yes, a cast of the Bacubirito meteorite was in that exhibit. Said cast remained on display for several / many decades and… You doubt that, my skeptical reading friend? Here is the proof...

The cast of the Bacubirito meteorite on display at the United States National Museum, Washington, District of Columbia. Jerry O’Leary, Jr., “Know Your Smithsonian.” The Sunday Star Magazine, 29 March 1959, 3.

Over the years, many scientists (geologists, astronomers, etc.) and many tourists and curious travelled to Sinaloa to see and touch the famous extraterrestrial phenomenon that was the Bacubirito meteorite. In 1924, one of those curious people was none other than the President of Mexico, Álvaro Obregón Salido.

A Mexican government authority, seemingly the municipal commissioner, Jesús Antonio Sepúlveda Velázquez, had a (stone?) shelter as well as a fence built to protect the meteorite from the elements, and humans, presumably during the 1920s. A person was also on site to monitor and protect the aerolite.

In 1959, the Bacubirito meteorite was transported to the Centro Cívico Constitución, a large park recently created in Culiacán, to facilitate its study, it was said. (Yeah, right…) That decision was in fact taken behind closed doors by a handful of muckymucks, possibly the governor and municipal president of Sinaloa, Gabriel Leyva Velázquez and Juan Bautista Obeso y Otilio Soto. Many people in the Bacubirito region were not particularly happy to see the meteorite go.

As was said (typed?) above, the aerolite was moved to the esplanade of the Centro de Ciencias de Sinaloa, in Culiacán Rosales, the new name of the city, in 1992, by order of the first director of that science centre, Antonio Mora Stephenson – or of the governor of Sinaloa, Francisco Buenaventura Labastida Ochoa. As of 2023, it was inside the brand new Centro de Ciencias de Sinaloa, to protect it from the elements and prevent long-standing cracks from becoming too large. The move seemingly took place after 2017.

A colloquium commemorating the 150th anniversary of the discovery of the aerolite was held in October 2013, at the Centro de Ciencias de Sinaloa.

Around 2017, I think, Mexican researchers asked the El Honorable Congreso del Estado de Sinaloa to pass a law making the Bacubirito meteorite an object of cultural and historical heritage of the state of Sinaloa. A prominent member of that congress and former rector of the Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa, in Culiacán Rosales, Víctor Antonio Corrales Burgueño, promoted the bill. The legislators saw no objection to adopting it in January 2018.

Today, in 2023, the mass of the stone fallen from the sky that is the Bacubirito meteorite, the largest Mexican meteorite known to date, is estimated at around 19.5 metric tonnes (19 imperial tons / 21.5 American tons). The composition of that iron / ferrous meteorite? 89 % iron, 7 % nickel and 4 % other elements.

This aerolite is of course a mere pebble compared to the huge aerolites which created the ginormous Chicxulub, Manicouagan, Sudbury and Vredefort craters, respectively located in Mexico, Québec, Ontario and South Africa.

Sweet dreams, my reading friend, sweet dreams. (Ominous music playing in the background)

Incidentally, A Blaze in the Northern Sky is the title of a highly influential 1992 album released by Darkthrone, an extreme / doom / death / black metal band from Norway. The words “a cinder of sidereal fire,” on the other hand, come from the 1946 poem Meteorite by the Anglo-Irish writer, poet and lay theologian Clive Staples “C.S.” Lewis. To quote the title of a 1988 song popularised by American singer / dancer / choreographer / actor Paula Julie Abdul, Opposites Attract.

Vaya con Dios, mi amiga / amigo de lectura, y ruega que el cielo no caiga sobre tu cabeza.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)