It was magnificent. It was splendid. It was pointless.

Greetings, my reading friend. How are you today? I can only hope that the fall weather is not affecting you too much. Would you be pleased to hear (read?) that the event at the heart of this week’s article took place in summer, a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away? All right, all right, our event actually took place on Earth but our planet was so different back then that one could argue it was an alien world. The year was 1943 and much of the Earth was in the throes of a cataclysmic conflict, the Second World War.

This conflict was a turning point in the history of many technologies that surround us, some of them good and some others bad, from antibiotics and helicopters to electronic computers and nuclear bombs. The technology at the heart of this article came into existence in the years that preceded the Second World War. It fell by the wayside during the years that followed this abominable period of the 20th century. This technology, say I, was the cargo / transport glider, a weapon used in combat for the first time in May 1940, by the German air force, or Luftwaffe, to land soldiers with more precision than one could expect when using paratroopers. Yours truly cannot say if, as a few sources state, cargo gliders were used in September 1939, during the invasion of Poland.

If the first cargo glider carried 10 people, pilot included, the aircraft makers of most of the great powers soon designed more imposing machines, capable of carrying more soldiers and / or a vehicle. By 1944, for example, a type of cargo glider used by the United Kingdom’s Royal Air Force (RAF) tipped the scale at 16 325 kilogrammes (36 000 pounds) when loaded. The aforementioned German cargo glider weighed a paltry 2 100 kilogrammes (about 4 630 pounds) by comparison. Would you believe that the Luftwaffe tested a ginormous 39 400 kilogrammes (about 86 900 pounds) cargo glider in 1941? This aerial giant eventually went into production as a 6-engine transport plane, but I digress. The first of many such digressions I’m afraid.

By and large, cargo gliders and the aircraft that towed them did not cover very long distances. This did not prevent several / many people from wondering if long / very long distance flights could be made by such dynamic duos. Gliders might be used to deliver urgently needed cargo to the United Kingdom, for example, or to fly back to North America the crews which ferried thousands of vitally needed aircraft across the Atlantic day in and day out. Such thoughts soon turned into action. In late 1942 or early 1943, the head of the RAF’s Transport Command called an experienced pilot into his office, in Dorval, Québec, at Montreal Airport (Dorval), as Montreal Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport was known back then. Air Chief Marshal Sir Frederick William Bowhill informed Wing Commander Richard Godfrey “Dickie” Seys, his son in law incidentally, that he had been chosen for a delicate mission. He and another pilot would fly a cargo glider across the Atlantic. The British pilot was horrified at the idea, but orders were orders.

Seys went to the United Kingdom to learn how to fly cargo gliders. He then flew to the United States to learn how to pilot the type of cargo glider he would fly across the Atlantic, the Waco Hadrian, an American design also / better known as the CG-4, its United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) designation. The machine chosen for the transatlantic flight was among the early examples made by a maker of piano parts, Pratt, Read & Company, a firm with no prior experience whatsoever in the making of aircraft.

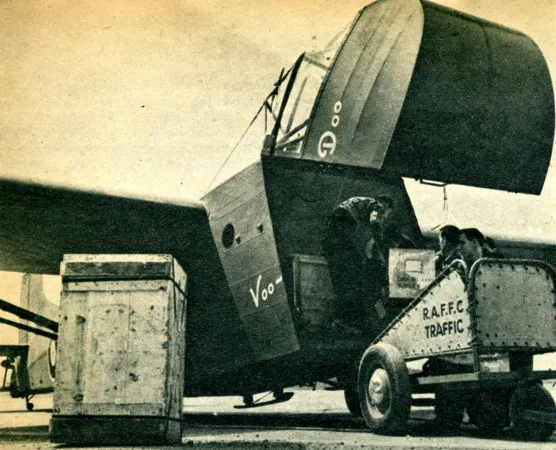

Seys named his glider Voo-Doo because he seemed to think this name was connected in some way with one of the great magic tricks in history and one that may have never been performed in its native land, the Indian rope trick. He was mistaken, of course, as Vodou / Vodù / Voodoo / Vudù had / has nothing do with India. These Afro-American religions in the Americas were derived from Vodun, a religion still practiced in 2018 by the Fon, in Africa. Yours truly must say that the likelihood that the Indian rope trick was a hoax caught me by surprise. And yes, my knowledgeable reading friend, the exceptional collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, includes a McDonnell CF-101 Voodoo supersonic jet fighter. And no, yours truly does not intend to pontificate on this remarkable machine.

In any event, in the spring of 1943, Seys used another Hadrian made by Pratt, Read & Company to conduct a series of test flights of increasing lengths and with more and more cargo on board. He seemingly shared the controls of the glider with a Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) pilot, Wing Commander Fowler Morgan Gobeil. The tow plane, a Douglas Dakota of the RAF, was seemingly flown by Flight Lieutenants William Sydney “Bill” Longhurst and Charles William Halliwell Thomson, 2 RAF pilots from Canada and New Zealand. These 4 men were fully qualified transatlantic pilots with Transport Command. Two other people from Transport Command joined the crew of the Dakota at some point. They were H. Gordon Wightman, a civilian radio operator from Canada, and Pilot Officer R.H. Wormington, an RAF flight engineer from the United Kingdom.

It should be noted that Longhurst joined the staff of Canadair Limited, an aircraft manufacturer based in Cartierville, Québec, in 1948. During the 1950s and 1960s, he tested most of the aircraft types produced by this subsidiary of an American defence giant, General Dynamics Corporation, namely:

- the North American F-86 Sabre fighter aircraft,

- the Lockheed T-33 Silver Star trainer aircraft,

- the Canadair CP-107 Argus maritime patrol aircraft,

- the Canadair CL-44 and CC-106 Yukon cargo aircraft,

- the Canadair CL-84 Dynavert experimental vertical take off and landing aircraft, and

- the Canadair CL-215 water bombing aircraft.

And yes, one can see a Sabre, a Silver Star, an Argus and a Dynavert in the stupendous, yes stupendous, collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum. And yes again, both Canadair and General Dynamics were mentioned in a July 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. Yours truly hopes that a CL-215, the very first purpose designed water bomber in the world if you must know, will one day be added to this collection, but back to the aforementioned test flights of Voo-Doo.

In April 1943, Voo-Doo and the Dakota left Montreal Airport (Dorval). They flew to North Bay, Ontario, and back to Dorval. A second non stop flight took the 2 aircraft to Maine. Soon after, the Hadrian and the Dakota made a roundtrip to the large RCAF airport at Goose Bay, Labrador, a part of Newfoundland, an all but colonial British territory at the time. This non stop distance world record was soon broken, however. Aware of the need to train over open waters, the Hadrian and the Dakota flew from Dorval to Nassau, Bermudas, in early May, with a few stops along the way. On the return trip, they flew all the way to Virginia, establishing a new non stop distance world record of 1 910 kilometres (1 187 miles), a journey that lasted a mind numbing 8 hours and 50 minutes. Yours truly would not be surprised to hear (read?) that this record remained unbeaten as of 2018. Now please remember that distance record, my reading friend.

It is worth noting that the journey from Virginia to Dorval was rather stressful. During the flight from Virginia to Washington, District of Columbia, Voo-Doo and the Dakota ran into severe turbulence in a clear blue sky. Besides its 2-man crew, the glider carried a passenger and a minimal amount of cargo, some coral rocks secured by ropes. The passenger hit the steel tube structure of the fuselage and was stunned. The rocks, on the other hand, broke free. Some of them punched though the floor and roof of the fuselage. Shocked by this turn of event, Seys, Gobeil and the passenger looked for any sign of damage. They found nothing. The coral rocks were re-secured and the flight continued. As the 2 aircraft reached a higher altitude, still in a clear blue sky, they ran into more turbulence. The passenger got tossed around and the coral rocks broke free yet again. As before, Seys, Gobeil and the passenger looked for any sign of damage. They found nothing. The coral rocks were re-secured and the flight continued. Had Voo-Doo been fully loaded, it was the crew’s opinion that its wings would have come off.

In spite of this close call, Gobeil, Longhurst, Seys, Thomson, Wightman and Wormington believed they were ready to cross the Atlantic. To help minimise the risks, the powers that be had decided well before that the flight would begin in North America to take advantage of the prevailing winds. Indeed, Voo-Doo and the Dakota would follow the ferry route linking the United States and Canada to the United Kingdom that 10 000 or so aircraft followed during the Second World War.

Before we look at this epic journey, yours truly would like to pontificate for a minute or three. Dakota was the name given by the RAF to the military transport planes known as the C-47 Skytrain or C-53 Skytrooper in USAAF service. More precisely, the Skytrain cargo carrier and Skytrooper troop carrier were military versions of the Douglas DC-3, a world famous airliner represented in, you guessed it, the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum. Voo-Doo's tow plane was one of the many Skytrains delivered to the RAF. Are we done with pontificating, you ask, my reading friend? We both know the answer to that question, don’t we?

A typical Waco CG-4 cargo glider. National

Even though Germany was the first country to use cargo gliders in combat, no place on Earth embraced these flying Trojan horses with greater enthusiasm than the United States. This was all the stranger given that only one American cargo glider actually saw combat, with the aforementioned USAAF. This machine, the equally aforementioned CG-4, was produced in greater numbers (about 13 905 examples, including 955 or so made by the Gould Aeronautical Division of Pratt, Read & Company) and in more places (16 assembly lines) than any other glider in history. The prototype flew around May 1942, soon after the signing of the first production orders.

Did you know that the CG-4's designer, Franklin A. "Frank" Dobson, was born in Ontario, in Bowmanville quite possibly? This graduate of Queen's University, in Kingston, Ontario, spent a couple of years studying in Germany, around 1936-38. Dobson worked for some time for the aeronautical section of an important manufacturer of railway rolling stock named Canadian Car and Foundry Company Limited mentioned in several issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since November 2018. Yours truly does not know when he moved to the Unites States.

Waco Aircraft Company, a small firm with limited resources and no prior experience in the production of aircraft for the American armed forces, found itself saddled with the task of helping the 15 other companies involved in the CG-4 production programme put up their assembly line. It had never done anything like that before. The same could be said of the fact that Waco Aircraft had to provide sets of detailed drawings to its partners, and to the many subcontractors involved in the making of parts. This situation was further complicated by the fact that several of Waco Aircraft’s partners had no prior experience whatsoever in the making of aircraft. Worse still, a few of them were barely a few months old and had yet to produce so much as a tooth pick. The many changes to the drawings of the CG-4 demanded by the USAAF only made things worse. To be blunt, the managing team at Waco Aircraft was out of its depth. By the way, the name Waco should be pronounced Waaco, not Wacko or Wayco.

If truth be told, the desire to produce the CG-4 as quickly as possible was such that no standardised production tooling was used. As a result, many parts and components were not interchangeable. This situation, a rather unusual one in the land of standardised, mass production, greatly complicated the work of the maintenance and repair crews working in the United States and overseas. All right, all right, maintaining and repairing CG-4s could be a bleeping nightmare.

The cherry on the cake, if yours truly may use this expression, was that the USAAF did not seem to have a clear policy, guideline or directive regarding the use of cargo gliders. It even seemed unable to decide how many it wanted or needed. As a result, the glider programme of the USAAF was a land of confusion from beginning to end, if I may quote the title of a 1986 Genesis song made popular by British singer and drummer Philip David Charles “Phil” Collins.

Quite a few CG-4s were delivered to the RAF, which operated them under the name Hadrian. You may be amused to hear (read?), or not, that all the cargo gliders flown by this service had names that started with the letter H. And no, yours truly was unable to figure out the number of Hadrians delivered to the RAF during the Second World War, which truly annoyed me. Sigh. A kind soul was kind enough, however, to point out that 1 145 CG-4s were delivered to the RAF.

Ten examples of a low powered, twin engined derivative of the CG-4, the PG-2, were produced but not used in combat. Toward the end of the Second World War, Waco Aircraft hoped that small transport companies would buy many CG-4s once peace returned and use the special conversion kits it had designed to transform them into cheap transport airplanes. The company put aside the idea in early 1945, a few months before the end of the conflict.

Would you believe that a Skytrain or Skytrooper flying at very low level could snatch a CG-4 right off the ground using a fairly simple grappling system? This spectacular / hair-raising technique was tested on several occasions in 1944-45, in the United States, France and elsewhere. It may have been used out of necessity for the first time in May 1945, to pick up the survivors of an airplane crash in New Guinea. At least one other glider snatch took place in Canada’s Northwest Territories, in April 1946, during a military operation known as Exercise Musk Ox.

After the Second World War, unknown numbers of CG-4s, hundreds if not a few thousands, were sold as war surplus. A great many were bought and discarded by people who wanted to use the wood of their large shipping crates. Other CG-4s were turned into hunting cabins, lakeside cottages and towed trailers by cutting off their wings and tail. A veteran bought 6 CG-4s in order to turn their shipping crates into cabins for a tourist camp. He wanted to use the wings of the gliders as porch awnings for these dwellings. Any remaining wood was to be used to make a hot dog stand and a bathhouse.

You may be pleased to hear (read?), or not, your choice, that the RCAF received 4 Hadrians in September 1944. It also acquired 28 ex-USAAF machines, as well as a single PG-2, in 1946-47. Even though some of the gliders remained operational until June 1955, at least in theory, they had a rather brief active career in Canada. The term brief was most appropriate indeed given that, by 1950, precious few people, even in the United States, were still promoting / defending the cargo glider. Another type of flying machine perfected during the Second World War, the helicopter, had a lot more to offer to both military and civilian operators. The United States Air Force (USAF), the new name of the USAAF adopted in September 1947, pulled out of the glider business in 1950, for example.

It is worth noting that several CG-4s of the USAAF took part in the aforementioned Exercise Musk Ox. Held between February and May 1946, this very useful military operation, one of the largest, if not the largest exercise ever conducted in Canada’s northern regions, was publicly described as a test of military equipment and capabilities conducted by the Canadian and American armed forces. A less overt but equally important goal was to reassert Canadian sovereignty in these same regions, given the American presence there both during and after the Second World War, but back to our story. Apologies for the numerous digressions.

The transatlantic flight began on 23 June 1943. Voo-Doo was towed by a Dakota of the RAF fitted with additional fuel tanks. The heavily loaded tow plane, a flying gas tank for all intent and purposes, struggled into the air. The fact that Voo-Doo carried 1 360 to 1 525 kilogrammes (3 000 to 3 360 pounds) of assorted cargo did not help. These (urgently?) needed items consisted of blood plasma or vaccine destined for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, as well as radio, engine and aircraft parts, and a banana bunch. The blood plasma / vaccine, the radio parts and the banana bunch were quite fragile and… What’s this, my reading friend? Why the giggles? You will know that bananas could not be bought anywhere in the United Kingdom during the Second World War, at least not legally. Seys put a bunch of bananas on Voo-Doo so that his family in England could enjoy these delicious and nutritious fruits.

A Consolidated Catalina maritime patrol flying boat on its way to the United Kingdom joined the Hadrian and the Dakota soon after take off. Its crew was given the unenviable task of rescuing their crews of the other aircraft if they had to ditch in mid ocean for some reason or other. Given the presence of extensive ice packs and / or heavy seas in the North Atlantic, one has to wonder if a rescue attempt would have been successful. In any event, the lack of emergency exit on top of the Hadrian’s fuselage might have proved fatal for Seys and Gobeil. Incidentally, many people at Montreal Airport (Dorval) feared that the transatlantic journey would end badly. Odds of 5 to 1, even 7 to 1 perhaps, were laid against a successful crossing. There were no takers.

The first 4 hours of the flight were uneventful. Even so, Seys and Gobeil had to remain alert, at the controls, in case something went wrong. The near perfect weather slowly took a turn for the worse, however. Massive storm clouds came into view. Unable to climb above them, Voo-Doo, the Dakota and the Catalina were forced to fly below them, where they encountered very heavy turbulence. One moment, the glider was 6 metres (20 feet) above and behind the Dakota. A moment later, it could be 30 metres (100 feet) below and to one side of the tow plane. The Hadrian’s speed could go from close to 260 kilometres/hour to less than 155 kilometres/hour (160 to 95 miles/hour) in matter of seconds. The strain on the Nylon tow rope was tremendous as it went from hanging like a limp noodle to snapping as straight as a violin string.

Seys and Gobeil were powerless to control the Hadrian as the wind tossed it around like a leaf. The cargo stored behind them began to shift, a potentially dangerous situation. More ominously perhaps, ice began to form on Voo-Doo's wings. So much snow was falling that Seys and Gobeil rarely saw the Dakota. They talked with Longhurst and Thomson over the radio on several occasions to see whether or not they should turn back. The 4 men decided to carry on. All in all, the crews had to battle 3 snow storms. After 3 or so hours in hell, the airport at Goose Bay came into view. Seys and Gobeil cut loose from the Dakota and landed without a hitch. Longhurst and Thomson followed suit. Every crewmember was exhausted. Voo-Doo’s presence caused quite a stir, as it was the first cargo glider to land at Goose Bay.

The second leg of the journey took place on Sunday, 27 June, with the return of suitable weather. Voo-Doo, the Dakota and the Catalina were soon over the Atlantic. Understandably enough, all crew members were rather nervous. For most of the flight, the 3 aircraft travelled over a solid cloud cover. Mountains in Greenland came into view about 5 hours after take off. Soon after this, 3 squadrons of USAAF twin engine medium bombers, Martin B-26 Marauders if you must know, my aeronautically enthusiastic reading friend, went by the Hadrian and the Dakota. Their cruising speed was so much higher than that of both aircraft that Seys and his companions wondered if they were in fact moving backwards.

This feeling was akin to a phenomenon known as vection (Hi there, EP / EG or EG / EP! Sorry, private salutations.) If yours truly may be permitted to quote the website of the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), the word vection may be defined as “a feeling that you are moving even though you are immobile, brought by seeing something else moving.” Such an illusory motion can be dangerous for astronauts / cosmonauts / taikonauts if it leads them to misinterpret the speed and direction of other objects.

Given this, I am pleased to inform you that the CSA sponsored the development of a science experiment known as, yes, you guessed it, Vection which uses a specially designed virtual reality system to examine how microgravity affects International Space Station (ISS) crew members’ perception of their movements. This being said (typed)?, the results of this experiment could also be of use during future missions to the Moon or Mars. The research team behind this experiment came from York University in Toronto, Ontario. Seven astronauts (and cosmonauts?) are to be tested before, during and after their mission to the ISS. Vection is scheduled to take place between 2018 and 2022. It is worth nothing that Canadian astronaut David Saint-Jacques is one of the individuals involved in this experiment, but back to our story.

The final stage of the 27 June flight of the transatlantic journey was a landing at Bluie West 1 / Bluie West One / BW-1, an American air base located in a narrow fjord in Greenland surrounded by towering, snow covered mountains – a somewhat daunting prospect when flying a heavily loaded glider. Much to their relief, Seys and Gobeil experienced no real difficulty, thus completing the first landing of a cargo glider in Greenland, a Danish colony occupied by Allied troops at the time. The following day, someone noted that one of the 3 strands at each end of the tow rope was almost worn through. While resplicing said rope took little time, changes in the weather meant that the crews of the Hadrian and the Dakota remained grounded for the next 2 days. They passed the time resting, fishing, eating, etc.

Would you believe that Eystribyggð, the first permanent European settlement established in Greenland, in 985, stood very close to where Gobeil, Longhurst, Seys, Thomson, Wightman and Wormington rested, fished, ate, etc. The group of Viking colonists / invaders behind this achievement was led by Eiríkr Thorvaldsson, also known as Eiríkr Rauð, or Eric the Red. His son, Leif Eiríkrsson, led the first group of Europeans known to have set foot on the mainland of the Americas, around 1000, and I digress. Again. Apologies.

Voo-Doo, the Dakota and the Catalina left Greenland on 30 June after a first class check up by USAAF ground crews. Unable to clear the mountains surrounding Bluie West 1 with a heavily loaded glider in tow, the heavily loaded Dakota had to fly down a fjord filled with icebergs to reach the open sea, a procedure that no one had tried before. It actually left the ground 60 or so centimetres (2 feet) before the end of the runway, which happened to be where the land met the water. Unable to climb above the highest peaks of the Greenland ice cap, Voo-Doo and the Dakota had to follow the coast as they travelled to their next destination, Iceland, an independent country associated with Denmark at the time that was also occupied by Allied troops. The Catalina kept them company as usual.

Voo-Doo and the Dakota ran into thick low lying clouds, with intermittent rain squalls and heavy turbulence. Worse still was the fog, which extended right down to sea level. Seys and Gobeil soon lost sight of the Dakota. Violent gusts of wind shook the glider like a leaf. Ice began to form on the wings of Voo-Doo and the Dakota. Moisture in the glider’s fuselage actually condensed and fell as snow. As this took place, the 2 aircraft gradually climbed out of the danger zone. It began to snow. After experiencing some very violent bumps, Voo-Doo and the Dakota broke through the clouds. They found themselves in a clear area between 2 layers of thick clouds. Their ordeal had lasted a full hour. The clouds below Voo-Doo and the Dakota gradually disappeared, followed by those above them.

Sometime thereafter, all 3 crews saw the mountains of Iceland on the horizon. They were much relieved by the prospect of landing earlier than they had expected. As time went by, however, the coastline of the large island failed to appear. The men came to realise that what they had seen were massive clouds on the horizon. The same mirage appeared 2 more times until the real mountains of Iceland came into view. Three USAAF fighter airplanes met Voo-Doo, the Dakota and the Catalina, and escorted them to the RAF base at Reykjavik. Their presence was deemed necessary given the possibility that a German aircraft flying over the Atlantic to gather meteorological data could attack the unarmed transport airplane and glider.

After their landing, the crews of Voo-Doo and the Dakota were informed that the tow rope had suffered some damage. Unable to drop this crucial item on a grassy area near the airport, as it did throughout the journey, because there were too many houses nearby, the crew of the transport airplane had to drop it over the airport. The 2 metal ends of the tow rope were badly damaged when they hit the hard surfaced runway. A ground crew at Reykjavík worked on said rope throughout the evening and night. It also checked Voo-Doo, the Dakota and the Catalina. As this was taking place, the crews ate, did a tiny bit of sightseeing and rested.

The 3 aircraft left Iceland on 1 July, which happened to be Dominion Day, Canada’s national holiday, known in 2018 as Canada Day. Unwilling to fly into low clouds over the hills at the end of the runway, Voo-Doo and the Dakota had to make a steep turn to the right soon after leaving the ground. As the 3 aircraft began to climb to their cruising altitude, they were faced by severe turbulence. Upon reaching said cruising altitude, the air became smooth. The USAAF fighter escort their crews requested by Seys failed to show up, as did the RAF fighter escort that was supposed to accompany Voo-Doo, the Dakota and the Catalina as they got close to the United Kingdom. Lucky for him and his teammates, no German aircraft flew by during the journey. Even so, everyone kept a sharp lookout.

The next 2 hours were uneventful, if somewhat stressful, with a bright sun shiny day above and solid clouds below. These gradually broke up as clouds began to form above Voo-Doo and the Dakota. The crews soon ran into very heavy rain squalls. The aircraft were severely buffeted by turbulence. This stretch of bad weather went on for some time. Voo-Doo and the Dakota eventually reached an area of fine weather. An hour later, the crews sighted a minuscule island. The United Kingdom was now close by.

As the 3 aircraft made landfall, in very thick haze, they flew into one of the many imposing barrages of captive balloons which protected many British strategic areas. No one in Reykjavik had mentioned that serious hazard – a serious lapse in judgement if yours truly may say so. The pilots of Voo-Doo and the Dakota barely had the time to make a steep climbing turn to avoid colliding with one of the balloons. The tow plane actually flew directly over the glider while going in the opposite direction. The Catalina left Voo-Doo and the Dakota at some point after this unnerving encounter.

Before long, the glider and its tow plane were over the airport at Prestwick, Scotland. They circled the area for some time, hoping that the newsreel camera aircraft which was supposed to immortalise the end of the journey would appear. It did not. The sky became increasingly cloudy, threatening to block access to the airport. Well aware that the welcoming committee had arrived, Seys and Gobeil cut loose from the Dakota, dove through the clouds and landed at Prestwick without a hitch. The 2 men shook hands. Longhurst, Thomson and their crewmates landed shortly thereafter. The first and only transoceanic flight made by a glider towed by an aircraft was over. Voo-Doo and the Dakota had covered a distance of approximately 5 650 kilometres (3 500 miles) in 28 hours and 3 minutes of actual flight time, spread over 8 days. And yes, the average speed of the 2 aircraft was a breathtaking 201 kilometres/hour (125 miles/hour).

A work crew took the blood plasma / vaccine, as well as the radio, engine and aircraft parts out of Voo-Doo and sent them on their way. Sadly enough, Seys’ banana bunch got frostbitten during the journey and had to be disposed of. Before going in a nearby building for debriefing, Seys and Gobeil picked up their mascots, a red skullcap made from an old hat worn by his wife, and an ornamented pendant from New Zealand known as a hei-tiki.

A conference held in London around July 1943 concluded that the creation of a regular transatlantic glider service was not feasible given the limitations of the gliders and tow planes available at the time. If truth be told, a Dakota could have delivered the cargo carried by Voo-Doo with a lot less hassle. This was pretty much the conclusion of a brief article published in the 9 July 1943 issue of the British weekly The Aeroplane. Oddly enough, the page that followed this article contained a photo of the ginormous 6-engine German transport plane mentioned above.

Given the successful, dare one say (type?) lucky, conclusion of the transatlantic flight yours truly has spent so much time talking (typing?) about, someone in authority decided that Voo-Doo should be donated to a British national museum in London, presumably the Science Museum, and put on display for future generations to see. The glider and another (Dakota?) tow plane thus left Prestwick in early to mid July 1943. Sadly enough, Voo-Doo crashed while landing at some airport in England. The ferry crew was not injured but the glider had to be scrapped. If I may say so, sic transit gloria mundi, or thus passes the glory of the world.

You may be equally chagrined to hear (read?) that the Dakota used for the transatlantic flight was destroyed in March 1945, in the Azores, a Portuguese archipelago in the Atlantic, when it swerved on take off and hit another aircraft. Its crew seemingly walked away. On the other hand, you may be interested to hear (read?) that the Catalina which escorted Voo-Doo and the Dakota spent some time at the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment in the United Kingdom, where it was used in to test anti-submarine unguided rockets. It was seemingly dismantled in October 1944. And yes, an example of a Canadian-made version of the Catalina known as the Canso can be found in the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum. And yes, I forgot to say how amazing that collection was. Sorry, that won’t happen again.

You may pleased to hear (read?), or not, that 2 (or more?) pieces of the tow rope have been preserved. One of these went to Pratt, Read & Company. It was given later on to the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington. Another piece, signed by the 6 people involved in the transatlantic flight, was mounted on a wooden board. It seemingly found its way to the Museum of Army Flying at Middle Wallop, England.

Interestingly enough, another glider produced by Pratt, Read & Company earned a world record. Let me explain. Why these tears of despair? We are making progress. Yes, we are. As I was saying (typing?), in March 1942, the company tested a 2-seat training glider of its own design, the PR-G1, in the hope of obtaining a USAAF order. By the time this service examined this robust and well crafted aircraft, it had unfortunately ordered several types of training gliders. Pratt, Read & Company did not get a contract. It so happened, however, that one of the machines ordered by the USAAF was of interest to the United States Navy. This service soon realised that any contract it signed would not be fulfilled for some time, which was a problem.

You see, my reading friend, the United States Navy was planning to use amphibious cargo gliders operated by the United States Marine Corps (USMC) to help retake various Japanese-occupied territories in the Pacific theatre of operation. These actions would take place in conjunction with more conventional landing operations. The pilots of the cargo gliders would have to be trained, of course.

The United States Navy soon concluded that the PR-G1 might offer a solution to its training problem. It signed a contact with Pratt, Read & Company in 1942, for the production of 100 LNE training gliders. As the practicality of amphibious cargo glider operations came under fire, however, the number of LNEs on order was cut to 75. In the end, quite possibly before the start of 1943, the United States Navy (and / or the USMC?) concluded that amphibious cargo gliders would not be all that useful. None of the designs it had ordered was put in production.

Would you believe that a photo of one of the amphibious cargo gliders developed for the United States Navy was to be found on the page of the 9 July 1943 issue of the British weekly The Aeroplane that followed the one on which one could read the somewhat dismissive article mentioned above? Small world, isn’t it?

The cancellation of the United States Navy’s cargo glider program meant that all but 2 of the LNEs ended up with the USAAF. Given that this service already had most, if not all of the training gliders it needed, the Pratt, Read & Company gliders, now redesignated TG-32s, were not taken out of their crates. Their sale to civilian pilots seemingly began in 1944, as the Second World War still raged across the globe. A buyer willing to travel to the USAAF base where the TG-32s were stored in order to assemble his glider and have it towed away would get a rebate. Several sharecroppers who lived near that base bought the large wooden crates used to deliver the gliders and turned them into dwellings – a shocking state of affairs in the wealthiest country in the world.

The postwar career of the TG-32 was unexceptional, with one exception. And yes, my out of patience reading friend, you are about to hear (read?) something about the second world record earned by a glider made by Pratt, Read & Company. The USAF, the United States Navy and the University of California, Los Angeles, acquired 2 TG-32s for use in a daring high altitude and flight condition research program, the Sierra Wave Project, conducted in a region where high winds and extreme turbulence were to be expected. In March 1952, one of these specially equipped gliders reached an altitude of 13 488 metres (44 255 feet). This world record for 2-seat gliders remained in the books until August 2006, yes, 2006, when a modified Glaser-Dirks DG-500 known as Perlan I climbed to 15 461 metres (50 727 feet). One of the people aboard this high tech machine was James Stephen “Steve” Fossett.

You may be interested to hear (read?), or not, that this American pilot, businessman and adventurer was one of the 2 people involved in a commemoration of the first non stop transoceanic flight, between Newfoundland and Ireland, made in mid-June 1919, by British aviators John William “Jack” Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown aboard a specially equipped Vickers Vimy twin engine bomber. The aircraft used for this commemoration, made in July 2005, was a Vimy replica completed in 1994. Fossett and his co-pilot spent a few days in Ottawa in June 2005. They and their aircraft spent some time at the Canada Aviation Museum, as the Canada Aviation and Space Museum was called back then. Yours truly saw the Vimy from up close and was most impressed. This aircraft was donated to the Brooklands Museum, in Brooklands, England, in 2006.

Is this all for today, you ask? Well, not quite. A brief video on Voo-Doo’s journey can be found at

The British narrator suggested that the journey might become the foundation of the gliding merchant service of the future, presumably after the end of the Second World War. As things turned out, such a service never came into existence. Yours truly did, however, come across a 1946 (?) advertisement which showed civilian CG-4s used to transport cargo. This ad was published by Distillers Corporation-Seagrams Limited, a Canadian company and one of the largest distilleries in North America. And that’s it for today.

What’s this, my reading friend? You wish to know what happened to Pratt, Read & Company and Waco Aircraft? Really? Ahhh, you bring tears to my eyes. Well, the former went back to making piano parts before gradually turning its attention to the production of screwdrivers. If truth be told, Pratt, Read & Company eventually became the 3rd largest manufacturer of screwdrivers in the United States. Sadly, it filed for bankruptcy protection in March 2009. By then, Pratt, Read & Company was one of the oldest manufacturing concerns in the country. A company by the name of Ideal Industries Incorporated acquired its name and tooling in March 2010. It moved the tooling to another location and founded Pratt-Read Tools Limited Liability Company, which still existed as of 2018.

Waco Aircraft was not so lucky. The company had invested so much of itself in the glider making programme that it did not properly prepare for the postwar period. The safe, reliable, elegant and comfortable private airplanes it was known for before the Second World War, biplanes one and all, were obsolete. Desperate to stay afloat, Waco Aircraft did design a new machine, though. Test flown in March 1947, the odd looking and radical Model W Aristocraft suffered from various problems. Construction of a second and much improved prototype began in the spring. This aircraft was not completed. In early June, Waco Aircraft laid off many employees and suspended work on the certification of the Aristocraft. Around July 1947, the company announced that it would no longer produce complete aircraft, a sad turn of event for one of the great names of the American aircraft industry of the 1920s and 1930s.

Before I forget, would you believe that an American by the name of Terrence O’Neill acquired the aforementioned Aristocraft in 1962? He thoroughly modified the aircraft at some point in the second half of the decade. The propeller of the Aristocraft II, also known as the Model W Winner, was no longer at the rear, for example. It was mounted at the front of the new aircraft. I wish I could say (type?) that O’Neill Airplane Company was successful in commercialising the Aristocraft II, in the late 1960s, but that would be a lie.

Waco Aircraft managed to stay afloat by making a wide variety of aeronautical support equipment. The company also had to produce non aeronautical items like the Orbitan sun lamp, “the sunlamp with a moving sun,” and the Lickity Log Splitter, a device invented by its president at the end of the 1950s.

And yes, the mind blowing collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum does include one of the safe, reliable, elegant and comfortable private airplanes made by Waco Aircraft before the Second World War, a Waco VKS cabin biplane to be more precise.

A firm by the name of Allied Aero Industries Incorporated acquired Waco Aircraft in 1963 and promptly sold its obsolete tooling. The former aircraft manufacturer was seemingly gone for good. Incidentally, a company by the name of Piqua Engineering Company acquired the production rights of the Lickity Log Splitter and kept an assembly line busy until 1971.

Allied Aero Industries is worth mentioning because it was apparently the American representative of a small West German company, Wagner Helicopter Technik, whose Aerocar roadable helicopter was mentioned in an August 2017 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. Allied Aero Industries also owned at least 3 declining / struggling aviation related companies besides Waco Aircraft. One of these was Omega Aircraft Corporation, acquired around 1963-64.

That company is of interest, at least to yours truly, because its founder was none other than Bernard W. “Bernie / Snitz” Sznycer, a Polish-American engineer who designed the first successful helicopter flown in Canada, with the help of an American friend and colleague, the first female engineer involved in helicopter design if you must know, Selma G. Gottlieb. This helicopter was the Intercity SG-VI Grey Gull. Would you believe that the prototype of this machine flew for the first time in July 1947, in Dorval? Intercity Airlines Company belonged at least in part to the largest intercity bus company in Québec, the Compagnie de transport provincial, a subsidiary of Montreal Tramways Company.

The one helicopter designed by Omega Aircraft was the SB-12 / BS-12. Sznycer developed this machine, the world’s first flying crane, with some input from Okanagan Helicopters Limited, a Canadian company mentioned in an October 2017 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, and the largest operator of civilian helicopters in the world at the time. Only 3 or 4 BS-12s left the factory before Omega Aircraft went out of business around 1965.

Are we done yet, you ask, my weary reading friend? Well, almost. We are making progress, really. The lingering fame of Waco Aircraft was such that SIAI-Marchetti Società per Azioni and Allied Aero Industries signed a deal in 1966 according to which the Italian aircraft maker would sell, reassemble, assemble and / or produce several of its private airplanes in the United States. A born again Waco Aircraft Company would commercialise these machines with the help of a number of dealers, including at least one in Canada, more specifically in Ontario. Interestingly, many / most of the Italian airplanes would be upholstered by Carrozzeria Pininfarina Società per Azioni, arguably the Leonardo da Vinci of automobile body design.

Allied Aero Industries’ efforts to enter the private airplane market were nothing if not ambitious. A French aircraft maker, the Société de construction d’avions de tourisme et d’affaires (SOCATA), was also involved in its scheme, for example. This subsidiary of the Société nationale de constructions aéronautiques Sud-Aviation was formed in 1966 when the Gérance des établissements Morane-Saulnier was reorganised. Only a handful of Waco Minervas, the American name of a Morane-Saulnier short takeoff and landing single engine private airplane, were sold. As well, Allied Aero Industries and Procaer Progetti Costruzioni Aeronautiche Società per Azioni formed Allied Aero Industries Italia Società per Azioni in the fall of 1968 to supervise the production of yet another single engine light airplane in the United States.

The sudden death of Allied Aero Industries’ founding president, a Russian-American businessman and spiritualist informally / impolitely known as the “Junk Dealer,” in December 1968, seemingly dealt a fatal blow to the project. The total number of SIAI-Marchetti single engine private airplanes reassembled and sold in the United States as the Waco Vela, Sirrus and Meteor may not have exceeded 150. Worse still, the Italian company found itself saddled with a large number of disassembled airplanes, more than 200 perhaps, which no longer had a buyer. The prototype of the modified American version of the Procaer light airplane, which flew a week or so after Berger’s death, was not put in production. The projected reassembly and sale of a SIAI-Marchetti twin engine private airplane did not take place at all.

And yes, the Borel Morane monoplane on display at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, the oldest surviving aircraft to have flown in Canada as we both know, was seemingly made by the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Morane-Borel-Saulnier, a distant ancestor of the Gérance des établissements Morane-Saulnier. The aircraft produced between 1910 and 1912 by this company and its predecessor, the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Morane-Borel, were confusingly known as Morane, Morane Borel and Borel Morane. Some witty persons even called them Morel Borane. Similar machines were also made in 1912 and later by the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Morane-Saulnier and the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Borel, but I digress. Would you believe that a Société des aéroplanes Raymond Saulnier existed in 1909-10? Have I succeeded in thoroughly confusing you, my reading friend? Yes? That’s good to hear, because the history of aviation before the start of the First World War, in 1914, can be very confusing indeed.

Waco Aircraft may have gone out of business around 1971. Even so, the aura surrounding this aircraft manufacturer proved irresistible to many enthusiasts. Yours truly is therefore pleased to inform you that the WACO Historical Society Incorporated was founded in 1978. This group was still active in 2018. Better yet, Classic Aircraft Corporation was formed in 1983 to produce an upgraded version of a typical 1930s Waco open cockpit biplane. This company was also still active in 2018, under the name WACO Aircraft Corporation. And yes, my perspicacious reading friend, it is ironic that even though companies that bore the names of Pratt, Read & Company and Waco Aircraft were in business in 2018, neither of them had a direct link with these organisations.

And yes again, 1 or 2 typical Waco open cockpit biplanes, Waco UPFs owned by Ottawa Biplane Adventures Incorporated to be more precise, took off from Rockcliffe airport, a stone’s throw from the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, during the spring, summer and fall of 2018, as they had done for many years, and... All right, all right, if you insist, I may, I repeat may, pontificate on the Aristocraft and / or the Grey Gull at some point in the future. Now, please go home. This was an exceedingly long text, even by my own, supremely verbose standards. Yours truly needs a rest.

I wish to thank all the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, nor theirs.

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)