The great adventure of a fictional Québec pilot and amateur spy hunter who confronted an equally fictional Communist bad hombre at the dawn of a very real Cold War: The Julien Gagnon comic strip by Rémy / Normand Hudon

Hi, how are you, my reading friend? Yours truly is delighted to see (read?) that you are doing reasonably well. I too am doing reasonably well. However, I must admit that my old bones would feel a tad better if the federal, provincial and territorial governments of Canada got with the program and celebrated International Workers’ Day, or Labour Day, on 1 May, rather than on the first Monday of September but let us not dwell. We, after all, have an intriguing topic on our plate. Our weekly encounter with science, technology and innovation beckons. Still, solidarity forever, for the union makes us strong! Locatores, no opprimar operarios!

In veritate dico vobis, err, in truth, I say to you, it is less science, technology and innovation than history and popular culture, and aviation, that will hold our attention this week. As you may have guessed, the subject covered by our glorious blog / bulletin / thingee is a French language comic strip, Julien Gagnon, published from 16 May to 7 November 1948 in a very popular weekly newspaper of Montréal, Québec, Le Petit Journal.

Yours truly will teach you nothing by telling you that comic strips had occupied a significant place in Le Petit Journal for quite some time. Indeed, in September 1947, the management of that newspaper grouped together the various series it published in a magazine section of 16, then 24 pages, in January 1948. Better yet, that management wished to encourage local talent, an approach it was keen to mention in the pages of the weekly. And so it was that an adventure comic strip set in the South Seas and a police comic strip set in Montréal appeared in Le Petit Journal between September 1947 and May 1948.

The third comic strip created by a Québec artist was somewhat different. At the very request of the management of the weekly, the latter drew his inspiration from current events in Québec, Canada, North America and the world.

In mid-February 1946, readers of daily newspapers across Canada were stunned to read that unidentified people, allegedly federal employees and ex-employees, had transmitted confidential / secret information to an unidentified country with an embassy in Ottawa, Ontario. There had been numerous arrests and a royal commission of inquiry would submit a report. Some dailies did not hesitate to affirm that the secret of the atomic bomb had been betrayed. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was quickly blamed.

It should be noted that the quite secret Royal Commission to Investigate the Facts Relating to and the Circumstances Surrounding the Communication, by Public Officials and Other Persons in Positions of Trust of Secret and Confidential Information to Agents of a Foreign Power, the RCIFRCSCPOOPPTSCIAFP for short, all right, all right, I am just kidding. It should be noted that the quite secret royal commission had heard from at least one witness when that rocambolesque spy case became known to the public.

That was / is quite the name for a royal commission, was is it not? Anyone suffering from hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia would have every right to be uncomfortable in the presence of such a name. By the way, hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia is a real word. It can be defined as the fear of overly long words. I kid you not.

This being said (typed?), hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia and Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronukupokaiwhenuakitanatahu would count as only two words on a text panel prepared by a group of Canadian national museums yours truly was closely associated with for a third of a century – and half a lifetime. And yes, I still think that the number of characters would be a better way to evaluate the length of an ideal text on a text panel. What say you? (Hello, SB, EG, EP and VW!) But I digress.

To answer the question which condenses in your panicked little noggin, Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronukupokaiwhenuakitanatahu is the name given to a New Zealand hill. That Maori word translates as the summit where Tamatea, the man with the big knees, the slider, climber of mountains, the land-swallower who travelled about, played his flute to his loved one.

The spy case we were dealing with before I derailed our train of thought owed its origin to the defection, in September 1945, with many confidential / secret documents, of an employee of the cipher department of the USSR embassy in Ottawa mentioned in an October 2020 issue of our enlightening blog / bulletin / thingee, a lieutenant in the Glavnoye Razvedyvatel’noye Upravleniye, the main intelligence directorate of the USSR, more precisely, Igor Sergeyevich Gouzenko.

The royal commission published two interim reports in March 1946. These contained no information on the confidential / secret information obtained by the USSR. The commission published its final report in June. Ten of the people mentioned in this slab of more than 730 pages were sent to prison by Canadian or British courts. Nine other people were acquitted. According to several / many people, the Gouzenko affair marked / marks the beginning of the Cold War. (Hello, EG and VW!)

Would you believe that Gouzenko’s defection inspired an American semi-documentary thriller film which premiered around mid-May 1948? The Iron Curtain was partly filmed in Ottawa in November and, I think, December 1947.

The screenwriter wrote the screenplay for this feature film using a series of articles entitled “I Was Inside Stalin’s Spy Ring” which appeared between February and May 1947 in the American literary / family monthly magazine Cosmopolitan. Yes, yes, my reading friend, that Cosmopolitan. Gouzenko, whose English was limited to say the least, apparently wrote the content of these articles in Russian. The latter was apparently later translated into English and, perhaps, rewritten by one or two unidentified people.

Two adorable young people, Colleen Carter, 16 months, and Donald “Donnie” Inglis, 17 months, were among the extras hired in Ottawa for the filming of The Iron Curtain. Both were stand-ins for Christopher “Chris” Olsen, an adorable 15-month-old American who played Gouzenko’s son, Andrei Igorovich Gouzenko.

Would you believe that Inglis’ parents lived in one of the buildings at Royal Canadian Air Force Station Rockcliffe, in… Rockcliffe, Ontario, a stone’s throw from the location where the fabulous Canada Aviation and Space Museum now stands? Inglis was an employee of a major Ottawa daily, The Evening Citizen, incidentally.

Incidentally, again, some people who feared the film’s negative impact on American-Soviet relations, already quite tense it had to be admitted, and even some people who were broadly favourable to the USSR, might have tried to hinder the filming of the sequences on Ottawa soil. Those attempts failed.

Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation had embarked on said filming in part in response to remarks by the chairperson of the (in)famous House Committee on Un-American Activities of the United States House of Representatives, John Parnell Thomas, to the effect that American film studios did not make anti-communist films.

And the fact was that The Iron Curtain was the first Cold War American film of its kind, in other words a propaganda film. It was certainly not the last. One only needed to mention Sofia (premiered September 1948), Walk a Crooked Mile (September 1948), The Red Menace (August 1949), The Red Danube (September 1949), The Woman on Pier 13 (October 1949), etc., etc., etc.

If I may be permitted to answer the question which is gradually condensing in your little noggin, the Soviet government did not appreciate that type of film at all. At the end of February 1948, in the Soviet daily Pravda, for example, the very influential Soviet literary critic / journalist / satirist David Iosifovich Zaslavsky denounced the American gangsters who had produced The Iron Curtain and castigated the Canadian government for not having prevented said production.

That dreaded and redoubtable die-hard hatchet man of the cultural milieu of the Stalinist regime could (should?) have waited before tearing down The Iron Curtain. That feature film was in fact one of the most balanced and intelligent filmic representations of the early years of the Cold War. The films which followed often turned out to be excessive / bonkers in their denunciation of the USSR and its agents.

Denounced by American commentators who feared an increase in anger, anxiety and suspicion among the American general public, The Iron Curtain was more publicised than any other feature film released in 1948. The jury of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences totally ignored it, however, when it came to choosing the best film, actor, actress, director, etc., of the year 1948, but I digress. Was that academy mentioned several times in our simply awesome blog / bulletin / thingee since September 2019, you ask, my reading friend? Yes, it was.

In early May 1948, just days before the grand premiere of The Iron Curtain, the publishing house J.M. Dent and Sons (Canada) Limited of Toronto, Ontario, and Vancouver, British Columbia, a subsidiary of the British publishing house J.M. Dent and Sons Limited, published This Was My Choice, a book originally written in Russian by Gouzenko, then translated into English, perhaps by a certain Mervyn Black, and rewritten by Montréal sports journalist Andrew William “Andy” O’Brian.

This Was My Choice was also published in the United Kingdom in 1948, by… Eyre and Spottiswoode (Publishers) Limited, which was a tad curious. It went without saying that Gouzenko’s book was published in the United States in 1948, but with a very different title: The Iron Curtain. Oh surprise… It was not published in Québec, a paradise of anti-communism if there ever was one, however, or in France, which was also a tad curious.

Speaking (typing?) of curiosity, would you like to know the name of the artist who created the comic strip at the heart of this issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee? And yes, that was indeed a rhetorical question.

The pseudonym which accompanied Julien Gagnon’s first page, Rémy, hid one of the greatest Québec, or even Canadian, political cartoonists of the 20th century.

Montréal cartoonist Norman Hudon hard at work. Pierre Gascon, “Croquis et instantanés.” Photo-Journal, 30 June 1949, 7.

Normand Hudon was born in Montréal in June 1929. And no, he was not yet 19 when Julien Gagnon’s first page appeared in May 1948.

A great drawer since his childhood, Hudon won a prize in the spring of 1945 for the poster which publicised a eucharistic congress, organised / held by the Roman catholic church, in June, in Rosemont, Québec. That same year, he won the first prize in the poster competition launched by the famous Jardin botanique de Montréal as part of a vast campaign against weeds launched, it seems, within the framework of the annual meeting of the Association canadienne-française pour l’avancement des sciences (ACFAS) held in October in Montréal, at the Université de Montréal. And yes, ACFAS was indeed mentioned several times in our wonderful blog / bulletin / thingee since December 2018.

In July 1946, the important daily newspaper La Presse of Montréal began to publish, on the front page of the colour magazine section which accompanied its Saturday edition, several / many works by Hudon: a view of Dominion Square, in Montréal, and its superb tulips, a young woman walking in the rain on a country road, a couple in a sleigh visiting friends on New Year’s Day, etc. In July 1946, Hudon was 17 years old. At that age, yours truly barely knew which way was up.

In 1947, even before completing his secondary studies, Hudon enrolled at the École des beaux-arts de Montréal, where he specialised in illustration, drawing and decoration. It did not take long for him to shine. Would you believe that the management of that august institution deemed Hudon so talented that it apparently placed him in second-year classes on his first day in class?

In 1948, Hudon became a freelance cartoonist for two Montréal newspapers, the daily La Patrie and the weekly Le Petit Journal. He created Julien Gagnon and a police comic strip published in Le Petit Journal between November 1948 and May 1949. Le cirque Moréno was / is an original story inspired by an American comic strip, Lance Lawson, which appeared in Le Petit Journal in 1948-49 under a new title, Le détective Lanson.

In 1949, Hudon embarked for France to study at the Académie de Montmartre, an Paris, under the guidance of the director of that art school, the great French sculptor / painter / illustrator / draftsman / decorator / ceramist Joseph Fernand Henri Léger. He had paid for the many months spent there by selling caricatures and comic strips, working on ships which cruised on the Saint Lawrence River, etc.

Once back in Québec, Hudon returned to his position as a caricaturist. He also worked as a caricaturist in Montréal cabarets, and this for several years during the 1950s. He could often be seen at the Cabaret Saint-Germain-des-Prés, one of the most popular French language cabarets of the time, where future giants of the Quebec artistic community performed, people like Clémence Irène Claire DesRochers, Pauline Julien, Monique Leyrac, born Marie Thérèse Monique Tremblay, and Dominique Michel, born Marie Marguerite Jeannette Aimée Sylvestre.

Hudon of course exhibited in Montréal paintings made in various places in Québec. He was well known within the artistic community of the metropolis of Canada.

In February 1953, Hudon appeared on the airwaves of a brand new Montréal television station, CBFT of the Société Radio-Canada, a state radio and television broadcaster mentioned moult times in our wonderful blog / bulletin / thingee since September 2018. He was the official cartoonist of Télé-Scope, a popular weekly entertainment and information program hosted by Québec artist / foodie / humourist / journalist / lawyer / manager / oenologist / trade unionist / writer Gérard Delage. That presence made Hudon a well-known personality throughout Québec.

The Québec cartoonist also made a name for himself on American soil. In the spring of 1956, Hudon drew caricatures for the wealthy clientele of the famous Blue Angel nightclub in New York City, New York. He returned there at least once again, in the fall of 1959. Hudon also performed at least once around that time on the set of a well-known American variety show, The Steve Allen Show, hosted by Stephen Valentine Patrick William “Steve” Allen.

Hudon took part in a new weekly program devoted to caricature broadcasted by CBFT from August 1956 onward. He shared the set of Ma ligne, maligne with the show’s host, the great Québec actor Jean Duceppe, born Jean Hotte, and the great Québec caricaturist / painter Robert LaPalme. The latter was then delivering to his employer, the influential Montréal daily Le Devoir, caricatures which included deliciously nasty portraits of the Premier of Québec, Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis, a conservative and authoritarian / autocratic as well as populist and nationalist / autonomist individual mentioned on many occasions in our blog / bulletin / thingee since January 2018.

In October 1956, Hudon began co-hosting Aux gais lurons, a new weekly Montréal variety show also broadcasted by CBFT, a show renamed Au p’tit café by the time of its second episode. The cartoonist and his stage mates, a singer / comedian, the aforementioned Michel / Sylvestre, and the great Québec actor Pierre Thériault, made Au p’tit café one of the most popular television shows in Québec.

Hudon joined Le Devoir’s team in 1958 as a regular caricaturist. His caricatures of Duplessis, whom he transformed into a shabby miser sometimes represented in the form of a vulture, were also deliciously nasty. The one he drew following the death of that politician, in September 1959, was, let us face it, really mean. Like a lot of good people in Québec, Hudon abhorred Duplessis and everything that demagogue stood for.

Hudon joined La Presse’s team in 1961. He held the position of caricaturist until 1965, which did not prevent him from appearing more than once on television. Let us mention, for example, that Hudon and another great Québec caricaturist, Frédéric Back, were cast members of one of the most popular Québec television programs of the 1960s, Les Couche-Tard of the Société Radio-Canada, hosted by two giants of Québec television, Roger Baulu and Jacques Normand, born Raymond Pascal Chouinard. Mind you, he might also have delivered caricatures to a Montréal daily, Le Journal de Montréal.

Before I forget it, Hudon opened a boîte à chansons, L’Ardoise sur la butte, in Eastman, Québec, connected to the famous Théâtre de la Marjolaine, in June 1960. He may had put this project aside in 1964 when L’Ardoise sur la butte became Le Chat gris. Incidentally, Le Chat gris became Le Piano rouge in 2004, in honour of the piano played on site by a famous Québec songwriter / singer / pianist / actor, Claude Léveillée. It still existed as of 2023, as did the Théâtre la Marjolaine.

Incidentally, a boîte à chansons was / is a type of establishment, very popular in the 1950s and 1960s, where people listened to singers while having a drink and / or some food.

In 1967, Hudon produced a large work for the ceiling of a pavilion at the Exposition internationale et universelle de Montréal, or Expo ‘67, which was to take place from April to October, in… Montréal, an amaaazing world fair mentioned in several / many issues of our tremendous blog / bulletin / thingee since November 2020. He then produced a mural for the Humor Pavilion at Man and his World, the temporal extension of Expo 67 which opened in May 1968. Said pavilion closed its doors in 1981, I think.

Over the years, Hudon published several collections of caricatures: J’ai mauvaise mine (1954), La tête la première (1958), À la potence (1961) and Parlez-moi d’humour (1965).

At the beginning of 1968, Hudon launched Le Poing, a monthly humour magazine which seemingly did not stick around for long. He also created Académie Normand Hudon Incorporée of Montréal, in September 1970, to exhibit and sell paintings. That academy later became a correspondence art school. It might, I repeat might, have closed its doors fairly quickly. Hudon was indeed going through a rather difficult period at that time.

In 1972, Hudon began to paint paintings which tenderly and ironically illustrated aspects of Québec’s heritage, from alley scenes to nuns on bicycles.

Hudon remained active pretty much until his death in January 1997 at the age of 67.

If Hudon was inspired by Québec, Canadian, North American and world news to create the comic strip Julien Gagnon, yours truly believes that the eponymous hero of that comic strip, a fictional Québec pilot, might, I repeat might, have drawn his inspiration from a real person.

After all, the first image of the first page of the comic strip contained the following words, in translation: “Aviator officer of the [Second World War], Julien Gagnon piloted a transport plane between Canada and England.” In addition, an image on the last page contained the following words, pronounced by Gagnon, again in translation, “No, Maria, I am going back to long-distance aviation.” Could Gagnon have been a ferry pilot? Nothing proved / proves that. This being said (typed?), that possibility opens wide the door leading to a long and irresistible digression. Brace yourself, my reading friend.

Captain Louis Joseph Ernest Bisson of the Royal Air Force’s Ferry Command. Anon. “Record établi par le capitaine Louis Bisson.” Le Droit, 26 May 1945, 1.

Louis Joseph Ernest Bisson was born in Hull, Québec, in March 1909. He apparently wanted to become a priest but had to give up that dream.

In or around 1929, while on holiday, Bisson visited Lindbergh Field in Ottawa, a site now known as MacDonald-Cartier International Airport. His first flight was a revelation. Like many other young people of his time, he discovered a passion for wings. Indeed, Bisson began flying lessons a week after his first flight. He impressed his instructors at the Ottawa Flying Club, in… Ottawa. Juggling two jobs, at the famous pulp and paper firm E.B. Eddy Company Limited of Hull and as a door-to-door salesman, Bisson obtained his private pilot’s license in 1930.

Between 1932 and 1934, Bisson also managed to obtain his commercial pilot, radio operator, aeronautical mechanic and instructor licenses.

In 1931, Bisson and, perhaps, a few friends bought a small used aircraft which he used to make a living as best he could. That machine was apparently destroyed in 1933, during a botched landing.

Bisson’s career really took off around 1933, however, when he learned that a Societas Iesu / Society of Jesus missionary from Québec working with First Nations of Northern Ontario was taking flying lessons so that he could get around more quickly. Bisson communicated with Joseph-Marie Couture and offered him his services, free of charge. He was hired on the spot. Bisson would thus transport Couture from 1933 to 1936. He also gave him flying lessons.

At the same time, Bisson worked for Nipigon Airways Limited of Jellicoe, Ontario. Would you believe that he shared his salary with the missionary? Interestingly, Bisson became the owner of Nipigon Airways.

Bisson’s fame in his hometown was such that many people called him, in translation, the Canadian Lindbergh.

Towards the end of 1936, confident that Couture would do just fine on his own, the latter having obtained his private pilot’s license earlier in the year, Bisson offered his services to a French missionary bishop who was working in the Northwest Territories. Monsignor Gabriel Joseph Élie Breynat was delighted with the qualities of the Québec pilot. Bisson worked with that apostolic vicar of the Mackenzie between 1936 and 1940. As a reward for the work he had carried out during that period, the apostolic delegate of the Vatican in Canada and Newfoundland, Ildebrando Antoniutti, presented him with the Pro Ecclesia and Pontifice medal in June 1940.

It is worth noting that Antoniutti and Bisson knew each other. The Québec pilot had transported the Italian bishop all over northern Canada in the summer of 1939.

Bisson joined the staff of Prairie Airways Limited in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, in the late summer or early fall of 1940. He was the chief pilot there.

Around July / August 1941, Bisson joined the Royal Air Force’s Ferry Command, a largely civilian staffed command established in Canada to deliver / ferry overseas military aircraft manufactured in the United States and, later on, Canada.

Bisson received an important assignment in early 1942: to examine the possibility of delivering relatively small combat aircraft of the United States Army Air Forces to the United Kingdom, via Labrador, Greenland and Iceland. Accompanied by the pilots who helped him carry out this work, Bisson made the first delivery flight on that route. At that time, Bisson appeared to be the only francophone Canadian in Ferry Command.

While working for that organisation, Bisson traveled more than 3 000 000 kilometres (more than 1 860 000 miles) – 7.8 times the average distance between the Earth and Moon. He could very well be the first pilot to make more than 100 crossings of the Atlantic Ocean. In fact, Bison ended the war with 138 crossings to his credit and several flights around the world.

As he began to carry out more and more transport flights, Bisson carried important personalities such as the Prime Ministers of Australia and New Zealand, John Joseph Ambrose “Jack” Curtin and Peter Fraser, as well as the British Prime Minister, Winston Leonard Spencer “Winnie” Churchill, a famous politician mentioned many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since May 2019.

Louis Bisson received the King’s Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air in June 1942. He was made an officer of the Order of the British Empire in January 1944.

Bisson left Ferry Command in the spring of 1945. Returning quickly home, he went into business and got involved in his community. Bisson played a crucial role in the creation, around August / September 1945, of Hull City Transport Limited, one of the ancestors of the Société de transport de l’Outaouais. The public transit firm’s buses soon replaced the streetcars which were still serving Hull.

In February 1948, Bisson founded Logements de Hull Tenements Incorporée of Hull. The latter had many houses built in the Lac des Fées sector of Hull. A good sport, Logements de Hull Tenements indicated to employees of Hull City Transport that it would lend them the down payment allowing them to buy one of those residences. A bus driver who had not had an accident in the previous 12 months was even entitled to a rebate. Bisson and two of his brothers subsequently developed the Parc de la montagne sector.

Very interested in education, Bisson and a few friends founded Bibliothèque municipale de Hull Incorporée in 1953. The Bibliothèque municipale Saint-Joseph de Hull opened its doors in April of the following year. This was a first for this municipality which had become a town / city in February… 1875, on 23 February it seemed – a day which makes the aeronautical fibre of all Canadian aviation enthusiasts quiver, and… Sigh…

On 23 February 1909, John Alexander Douglas McCurdy, a gentleman mentioned many times since September 2017 in our incomparable but all too easily forgettable blog / bulletin / thingee, made the first controlled and sustained flight of a motorised aeroplane in Canada. End of the digression linked to your all too… flighty mind.

In June 1959, Bisson co-founded Association des bibliothèques municipales de Québec Incorporée, an organisation whose goal was to promote the development and creation of public libraries on Québec soil. Bisson was also one of the co-founders of the Commission des bibliothèques publiques du Québec in 1959. He held the position of vice-president of that organisation for a long time.

A great volunteer before the divine, Bisson settled in Chapala, Mexico, around 1977. He worked there with disadvantaged young people. Ordained a priest in 1986, Bisson was consecrated bishop in January 1989 by Dom Luis Fernando Castillo Méndez, patriarch of the Igreja católica apostólica brasileira, a Brazilian independent / dissident Catholic church founded in July 1945 which did not / does not recognise the infallibility of popes and rejects the celibacy of priests.

Bisson died in September 1997, at the age of 88.

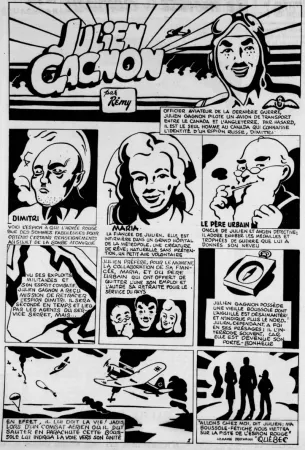

The great protagonists of the Julien Gagnon comic strip: Julien Gagnon and the diabolical Dimitri. Dollard Morin, “L’espionnage russe a inspiré à un jeune Montréalais le sujet des aventures illustrées de ‘Julien Gagnon.’” Le Petit Journal, 16 May 1948, 45.

And yes, the time has come to sum up the plot of the Julien Gagnon comic strip.

A ferry pilot during the Second World War, I think, the eponymous hero of said comic strip was, by chance, the only person in Canada able to identify a Soviet spy in search of information on the atomic bomb. The diabolical Dimitri did not act out of political conviction, however. Nay. He was looking for that information only to line his pockets.

Gagnon, on the other hand, went after that nogoodnik to protect his country, Canada. His fiancée, Maria, a nurse in a major Montréal hospital, and one of his uncles, Urbain, a retired detective, joined that heroic quest, a quest for which all these beautiful people did not receive so much as a dime.

My cinephile reading friend, do you happen to remember the broken compass of the somewhat deranged pirate Jack Sparrow, sorry, sorry, of the famous captain Jack Sparrow, a pirate of the Caribbean mentioned several times in our dazzling blog / bulletin / thing since September 2018? You know, the compass which pointed / points in the direction of the thing or person a character most desired. Well, Gagnon also used a broken compass to find the location of the person he wanted to find. I kid you not. That location was Québec, Québec.

Did Gagnon’s broken compass inspire that of Sparrow, you ask, my perplexed reading friend? I very much doubt that. Still, even stranger things have happened… You are here, reading this sentence, after all.

Yours truly will not bother you with a detailed account of the events which occurred in the course of the plot. You are welcome.

This being said (typed?), allow me to mention that the diabolical Dimitri initially eluded our hero. He rushed to Montréal where Gagnon and his adventure companions were quick to join him. The Soviet spy and his accomplices were nowhere to be found, however. Worse still, two of them attacked Gagnon and his uncle. The latter woke up in hospital with a nervous shock. Gagnon’s broken compass was then put to use again.

The plot reached its climax when the diabolical Dimitri and his accomplices found themselves surrounded in a warehouse after a car chase through the streets of Montréal. Gagnon entered said warehouse and shot one of the accomplices (!) with a pistol. A grenade he threw into the building (!!) killed another one. The surviving accomplices of the diabolical Dimitri wanted to surrender. The latter would hear none of it. He shot one of his accomplices. Fearing for his life, one of them then shot him. As the diabolical Dimitri died, all of the Soviet spy’s accomplices surrendered.

Unwilling to worry his fiancée, Gagnon gave up on a career as a detective. He announced to Maria that he would resume his career as a long-distance pilot, a job which was not without danger if I may be permitted a brief comment. The last panel of the Julien Gagnon comic strip showed the lovebirds in front of a church, just after their wedding.

If yours truly may be permitted to quote the consecrated formula, then defended by the Roman catholic church, Julien and Maria lived happily and had many children. Indeed, let us not forget, Québec women who married between 1946 and 1950 gave birth to 4 children on average. One in three had 5 or more children, but I digress.

See ya later, and profuse apologies for the length of this text.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)