A microcar designed in a time of austerity: The Bond Minicar

Before you hit the roof, my reading friend, please allow me to welcome you to the wonderful world of science, technology and innovation. And yes, it is true that there will be precious little aeronautical content in this week’s issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. All right, all right. I will include a bit more.

Let us begin, then, with a gentleman, an Englishman to be more precise, by the name of Lawrence “Lawrie” Bond. Born in August 1907, he worked in various engineering firms during the 1930s and early 1940s. Bond spent much of that time at Blackburn Aeroplane and Motor Company Limited / Blackburn Aircraft Limited. In 1944, he founded Bond Aircraft and Engineering Company Limited, to make aircraft and land vehicle components. Aeronautical content.

More aeronautical content. In 1935, the Canadian Department of National Defence asked the British Air Ministry to suggest a torpedo bomber which could operate on floats from isolated bases, in British Columbia for example, offering little protection against the harsh Canadian climate. The latter suggested it adopt the very robust and brand new Blackburn Shark – an aircraft designed to operate from the aircraft carriers of the Royal Navy. Blackburn Aeroplane and Motor / Blackburn Aircraft delivered 7 examples of this single-engine biplane to the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), in 1936-37.

Anxious to strengthen the defences of British Columbia, the Department of National Defence signed 2 additional contracts, around May 1937 and later in the year, with the only aircraft manufacturing firm in the region, Boeing Aircraft of Canada Limited of Vancouver, British Columbia. The relatively unadvanced nature of the Shark seemingly explained to a large extent the signing of contracts with an aircraft manufacturing firm which belonged to a well-known American firm, Boeing Aircraft Company. No military secret would be disclosed…

Hoping to improve the reliability of the new aircraft, the Department of National Defence requested that certain modifications be made, particularly in terms of the engine, considered unreliable. Fearful that said department could modify its purchasing policy in favour of American aircraft, the Air Ministry and Blackburn Aircraft proposed the use of the very reliable engine mounted on another British aircraft ordered by the RCAF, the Supermarine Stranraer maritime reconnaissance flying boat.

The British aircraft manufacturer, for whom this project was not a priority, did not deliver the equipment and parts that Boeing Aircraft of Canada needed as quickly as expected. The Department of National Defence may also have forgotten to order the Sharks’ propellers. In any case, the first aircraft manufactured in Canada did not fly until July 1939. The last of them entered service in 1940. The Canadian Sharks, virtually used all the time on floats, were obsolete before they even entered service.

Dare I say that the Shark had been obsolete since the entry into service in 1937 of 2 American and Japanese aircraft carrier-based torpedo bombers, the Douglas TBD Devastator and Nakajima B5N?

But back to our story.

In 1947, Bond completed a tiny and quite promising racing automobile but smashed it in an accident. He was hurt, but not too badly. Bond built 3 examples of a rather advanced racing automobile soon after.

Bond completed the prototype of a rather crude 2-seat convertible microcar, with no doors, designed for short distance travel and activities, for him and / or his second spouse, Pauline Freeman Bond, in early 1948. He did so on the first floor of the Bond Aircraft and Engineering building he lived in with said spouse, which meant that the oh so precious Bond Shopping Car had to be lowered to the ground floor, through a trapdoor, using chains and pulleys.

The interest shown by many people who saw his prototype on the road led Bond to wonder if a market existed for a microcar like his. His spouse contacted some of her friends in the newspapers industry in London, England, to see if they could write about the new vehicle. They did, and letters started to reach Bond. A vehicle based on the Bond Shopping Car would indeed sell.

Very much aware that his small shop could not accommodate a production line, Bond joined forces with a small local firm, which was faced with the likelihood of having spare space aplenty. You see, Sharp’s Commercials Limited, a subsidiary of Loxham’s Garages Limited, an automobile dealership, itself a subsidiary of the Bradshaw group of companies, had been informed that its contract with the British Ministry of Supply, which involved the conversion of military vehicles, mainly trucks, into civilian vehicles, would soon be terminated.

Given the serious limitations imposed on British motorists as result of the dire economic problems of the United Kingdom, Sharp’s Commercials’ management thought that Bond’s microcar could be a good seller.

As a result, Bond joined Sharp’s Commercials as a consultant while the latter thoroughly modified / improved the prototype, which became the Bond Minicar, which was announced in November 1948. A series of endurance runs kept the microcar, the first microcar put in production in the United Kingdom after the Second World War from the looks of it, in the news and confirmed that it consumed very, very little fuel. Underlined and exclamation point.

Production the Minicar began in early 1949. Sharp’s Commercials had such confidence in its potential that it acquired its design and production rights, which allowed Bond to work on other projects he has become interested in.

The projects in question were a series of scooters and small motorcycles designed and produced, in small numbers, by Bond Aircraft and Engineering. Several such vehicles were designed and produced during the 1950s. Bond Aircraft and Engineering sold the rights of the Minibyke to a textile machinery manufacturer, Ellis Leeds Limited, and those of the Gazelle to Project and Development Limited, a subsidiary of the aforementioned Blackburn Aircraft. Still more aeronautical content. The Oscar, a greatly improved Gazelle, proved very impressive but was not put in production. The last scooter made by Bond Aircraft and Engineering, or BAC as it was commonly called, seemingly left the factory around 1956.

And more aeronautical content. Interestingly, one could argue that the semi-monocoque aluminium alloy body of the Minicar resembled in a small way the semi-monocoque aluminium alloy fuselage of the aircraft Bond had worked on at Blackburn Aeroplane and Motor / Blackburn Aircraft. Mind you, the material used for the windshield of the Minicar was also standard issue on British Second World War era aircraft.

Bond founded a workshop / garage, Lawrence Bond Cars Limited, in 1956. That same year, he helped a caravan / trailer manufacturer, Berkeley Coachwork Limited, design an economical sports car with a fibreglass body. Berkeley Cars Limited made a few thousands of these rather popular, if slightly fragile vehicles. Production of the Sports came to an end in 1960, as the caravan market collapsed in the United Kingdom. An attempted sale of Berkeley Coachwork to Sharp’s Commercials fell through and both Berkeley Coachwork and Berkeley Cars closed their doors in 1961.

While the great majority of Minicars hit the road in the United Kingdom, Sharp’s Commercials was more than happy to provide assistance to foreign groups who thought that its microcars would sell in their homeland. A case in point was the fact that a Minicar was on display in the sports section of the T. Eaton Company Limited department store located in downtown Montréal, Québec, around April 1949. This presence may be linked to the fact that Sharp’s Commercials had a representative in North America, in the United States to be more precise, no later than 1949.

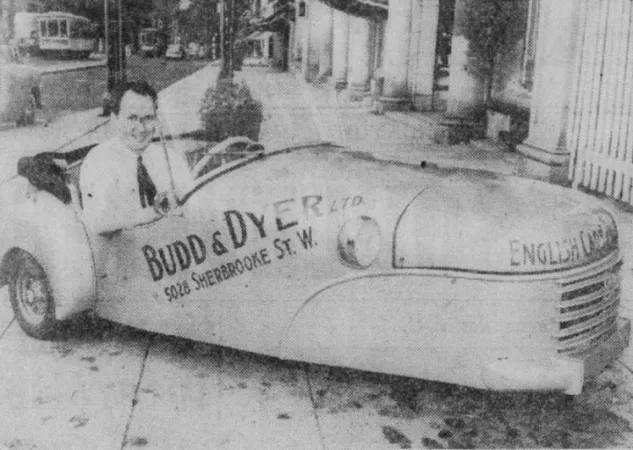

Another case in point concerned Budd & Dyer Limited of Montréal, a small firm founded in 1939 by Alexander “Alex” Robert Budd and Howard Buchanan Dyer. Back then, these gentlemen were mainly interested in motorcycles, either from a repair and / or accessory sale point of view. By 1950, Budd & Dyer were importing and distributing British automobiles.

The Minicar seemingly struck the firm’s fancy, as can be ascertained by reading, in translation, the caption of the photograph you saw at the beginning of this article.

We thought we had seen everything in the automotive sector in a reduced format…! But here is a Montreal importer announcing the placing on the market of a “real small car” whose fuel consumption index can rise to [2.6 litres / 100 kilometres / 92 miles / American gallon] 110 miles per [Imperial] gallon of gasoline, despite the advantage of a cruising speed of [more than 55 or 70 kilometres/hour] 35 or 45 miles per hour and a maximum speed of [more than 70 or 85 km/h] 45 or 55 mph, – because the automobile in question, the Bond “Minicar,” of British manufacture, can be driven at the choice of the buyer by a 5 or 8 hp engine, hence two efficiency classes for the same vehicle. The “Minicar,” whose distributor is the company Budd & Dyer, is designed as a road vehicle capable of accommodating two passengers in a cabin protected if necessary against the weather. The body is mounted on only three wheels, and the engine has the features of popular models of aviation engines, including air cooling.

As was to be expected, the Minicar was gradually improved over the years.

As well, Sharp’s Commercials introduced a couple of commercial versions of its vehicle in 1952. The single seat Minitruck was a slightly modified Minicar fitted with a flat platform in the spot where the passenger seat used to be. The 2-seat Minivan, on the other hand, had more cargo space and a rear access door. A version of this vehicle known as the Family Safety Saloon could accommodate 2 adults and 2 children, the latter in 2 hammock type seats which faced each other, and… Seatbelts? Come on, what planet are you from? Seatbelts… What’s this you say? An American automobile manufacturer, Nash Motors Company, began to offer seatbelts as an option as early as 1949? Pure hogwash. Seatbelts are dangerous, just like vaccines. And cigarettes are perfectly safe.

The arrival on the British market of another British microcar, the 3-wheeled Reliant Regal, in 1953, more or less forced Sharp’s Commercials to revamp the Minicar. A new steering mechanism made it possible for a good driver to do a series of 360 degree turns in a very, very tight space, for example. Other improvements added over the years included doors and a fibreglass hardtop.

This, by the way, was / is how one starts a Minicar…

Sharp’s Commercials launched its first real marketing campaign in the United States in 1953. The Bond Bear Cub, as the Minicar as known in that country, did not sell very well.

Much information on the various versions of the Minicar could be found in The Bond Magazine, first published in 1955. This quarterly publication also contained tips on Minicar repairs and home repairs, adverting from the makers of the many gadgets / doodads that could be mounted on Minicars and news from the various owners clubs in the United Kingdom – and perhaps elsewhere.

In 1959, a formidable competitor made its appearance: British Motor Corporation Limited’s Mini, one of the successful British automobile of the 20th century. Feeling the heat, Reliant Motor Company Limited introduced an improved Regal, which raised the bar for Sharp’s Commercials.

And yes, (s)he remembered! Thank you, oh Flying Spaghetti Monster! British Motor was indeed mentioned in August 2019 and November 2019 issues of our you know what. The Mini was mentioned in the former but not the latter issue of this interplanetary bestseller.

In 1962, the higher taxes which had penalised manufacturers of conventional, 4-wheeled automobiles since the end of the Second World War were brought down considerably. The yearly sales of Minicars took a turn for the worse.

Hoping to improve its financial situation through diversification of its production, Sharp’s Commercials produced a small number of scooters designed in house, the P series, between 1958 and 1962 or so.

In 1961, it acquired the European production and marketing rights of a personal watercraft developed by Power/Ski Incorporated. The Power/Ski consisted of a pair of floats on which 1 or 2 Homo sapiens could stand, with a small outboard engine at the rear. The catch with that Bond Power-Ski was that it made a lot more sense in California, where Power/Ski was located, than it did in ye olde wet and miserable United Kingdom. Very few (100 or so?) were made in that country until 1965. A small British firm, Kirkham’s Marine Limited, acquired the aforementioned rights around 1966 but, despite announcements that hundreds were to be produced, production of the Power-Ski seemingly did not proceed any further in the United Kingdom. Its American counterpart may not have been produced in huge numbers either.

The last Minicar left the factory in 1966. All in all, 26 500 or so vehicles, if not less, had been built – an infinitesimal number when compared to the production figures of the Mini (more than 10 million since 1959).

Before I forget, Sharp’s Commercials became Bond Cars Limited in 1964.

In 1963, the firm launched its first and only 4-wheeled automobile, the Bond Equipe GT 4-seat (2 adults and 2 children) sports car. Acting under contract, Bond himself designed the fibreglass body of this automobile. Would you believe that the Bond Equipe GT was designed to include some elements of a few other vehicles, including the Triumph Spitfire? And if that is not aeronautical content, yours truly does not know what is. Although quite good, the Equipe GT was not produced in large numbers (less than 4 400 between 1963 and 1970). Only one batch of these cute little automobiles came to Canada, more precisely to Midland Motor Sales Incorporated of Montréal, in 1969.

Bond Cars produced a new type of economical 3-wheeled automobile, a successor of the Minicar so to speak, designed by Bond himself, under contract, the 2-seat Bond 875, between 1965 and 1970. That year was very much a turning point for Bond Cars.

When the aforementioned Loxham’s Garages was sold to R. Dutton-Forshaw & Son Limited, a bigger car dealership, in 1968, Bond Cars found itself alone in this large conglomerate. As the only manufacturing firm in the group, it did not fit in. As a result, Bond Cars was put up for sale. Its management tried to buy the firm, but failed. Bond Cars’ old rival, Reliant Motor, acquired it in 1969.

If I may be permitted to go on a tangent for a moment, Reliant Motor began to produce a brand new personal watercraft in 1969. The Scooter Ski was surprisingly similar in concept and appearance to the Bombardier Sea-Doo, a personal watercraft introduced in 1968 and produced until 1970, which was the year the Scooter Ski also went out of production. Reliant Motor’s efforts to sell the Scooter Ski overseas had failed. Now, I ask you, was the inspiration of this British vehicle to be found in Québec, or were these 2 personal watercraft developed independently? If I may be permitted to quote the great Sherlock Holmes in the very popular 2009 eponymous motion picture, food for thought.

A typical Bond Bug microcar, England, October 2009. Wikipedia

And yes, Dax was / is (will be?) the name of a Trill symbiont, a squash-size teardrop-shaped intelligent life form native to Trill which can be surgically implanted in a humanoid Trill, but back to our story.

In 1970, Reliant Motor launched a brand new 3-wheeled microcar in which Bond was not involved at all, the 2-seat Bond Bug. If truth be told, the firm had been thinking about a fun to drive vehicle aimed at the younger crowd since at least 1964. With its bright orange fibreglass body, the wedge shaped Bond Bug certainly drew a lot of attention. All right, all right, it was the… grooviest automobile on any road. This being said (typed?), putting the pedal to the metal on a windy day could be a thrilling experience.

Legend has it that, when the organisers of the main automobile show in the United Kingdom refused to allow a Bond Bug on the premises because it was little more than a glorified motorcycle, the management of Reliant Motor was so infuriated that it ordered its staff to weld 2 chassis together to create a 4-wheeled super Bond Bug. Yours truly cannot say how that story ended. Pity.

Alleged problems with production and quality control, not to mention the cost of running its factory and that of Bond Cars, meant that Reliant Motor had to cut expenditures. As was said (typed?) above, production of the Bond 875 and Equipe ended in 1970. The Bond Cars factory was also closed down.

Production of the Bond Bug ended in 1974.

Would you believe that a Bond Bug chassis formed the basis of at least one of the vehicles used by a wet behind the ears Luke Skywalker in the 1977 movie Star Wars?

In the late 1980s, a firm formed for that very purpose acquired the moulds used to make the fibreglass body of the Bond Bug. Webster Motor Company wanted to produce kits of a 4-wheeled version of this vehicle that could be assembled in the home, attic or basement of homebuilders. Thirty or so kits were sold before Webster Motor went under, presumably in the early to mid-1990s.

In 1994, Reliant Motor launched an updated version of the Bond Bug, the Sprint. It was not put in production, and neither was the firm’s own 4-wheeled version of this vehicle, also known as the Sprint.

Sadly enough, Bond left this Earth in September 1974. He was only 67 years old.

Unwilling to let you go on such a sad note, may I offer you the following piece of music, recorded in 1998 by British entertainer / singer / songwriter Robert Peter “Robbie” Williams?

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)