Sorry, but no, the Wright brothers did not really invent the airplane: An all too brief overview of the piloted powered heavier than air flying machines fabricated and / or tested before 17 December 1903, part 3

Greetings, my reading friend, and welcome back to our all too brief overview of powered and piloted flight before the Wright brothers.

It is with sadness I begin this third part of our saga. You see, the story we are about to look into did not end well.

Percy Sinclair Pilcher (1867-99) was an English engineer / university lecturer who completed a triplane powered by a gasoline engine in the late summer of 1899. The design of that aeroplane was based on experience derived from a series of 4 very basic gliders put together somewhere in Glasgow, Scotland, I think, with the help of his older sister, Ella Sophia Gertrude Pilcher, and tested in 1895-96.

Indeed, would you believe that said sister was the first woman in the United Kingdom, if not the world, to pilot a heavier than air flying machine?

Pilcher’s hopes to test his triplane for the first time, on 30 September 1899, near Stanford on Avon, England, near Coventry, in front of a small group of potential sponsors, were dashed when a vital component of the engine snapped, presumably during some sort of ground test. Unwilling to disappoint his guests, he decided to pilot his best glider, and this even though the weather was both wet and windy. Tragically, a vital component of the soaked Hawk snapped soon after takeoff. Pilcher was critically injured in the ensuing crash. He died two days later. Pilcher was then only 32 years old.

James W. Clark (1862-1947) was an American clockmaker / inventor / bicycle repairperson who completed a gasoline-powered ornithopter with 2 pairs of wings mounted in tandem, at Bridgewater, Pennsylvania, in 1900. Interestingly, the wings of that flying machine were apparently covered with turkey feathers.

Clark’s early attempts to take off resulted in an accident. The ornithopter was rebuilt only to crash a second time. Clark rebuilt his flying machine again but decided to put it aside in 1903-04, possibly after hearing about the flights of the Wright brothers. That flying machine never flew.

Put aside in a carriage house, the Clark ornithopter was all but forgotten. A devoted collector of aviation-related books, memorabilia and photographs, Larry D. Lewis, President of Charles C. Lewis Steel Company, eventually heard about the old flying machine. He acquired it in 1976.

The Charles C. Lewis Foundation loaned the ornithopter to the Owl’s Head Transportation Museum, near Owl’s Head, Maine, in November 1993. That museal institution became the owner of that flying machine in December 2005. Now at least partly restored, the Clark ornithopter was on display at the Owl’s Head Transportation Museum as of early 2024. It may well be the oldest surviving piloted powered ornithopter in the world.

Need yours truly remind you that Clark was mentioned in an August 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee? I thought not.

The ornithopter completed by Georges Trice, Monte Carlo, Monaco. The blurry photo on the right shows Trice holding one of the wings of his flying machine Anon., “A New Bird-Like Aeroplane.” The New York Herald, 11 May 1901, 1.

Georges Trice (?-?) was a French individual who, around May 1901, completed an ornithopter in Monte Carlo, Monaco. Even though work on that flying machine had begun in early 1901, that gentleman had been interested in flight for some years.

Trice’s hopelessly underpowered bird-like aeroplane proved unable to fly.

A doctored photograph showing Némethy Emil’s Flugrad in flight. Anon., “Némethy új Repülőgépe.” Vasárnapi újság, 30 June 1901, 423.

Emil Karel Némethy (1867-1943) was an Austro-Hungarian factory manager / inventor / mechanical engineer who began to put together an aeroplane in 1899, at Arad, Austro-Hungarian Empire, today in Romania. His interest in flight was more or less that of a sportsperson. Némethy believed that, for aviation to become a sport, aeroplanes would have to be no more expensive than an automobile. His small and light flying machine, known as the Flugrad, was ready to fly no later than June 1901. It proved unable to fly.

To answer the question forming in your noggin, Vasárnapi újság means Sunday newspaper in Hungarian.

The second aeroplane completed by Emil Karel Némethy. Anon., “Némethys neuste Flugmaschine.” Illustrirte Zeitung, 14 January 1904.

Némethy completed another powered aeroplane in December 1903 or January 1904. It too proved unable to fly. Yours truly thought best to include it in this article, just to be sure.

Némethy completed a third powered aeroplane in 1910. It sadly proved as unsuccessful as its predecessors.

Wilhelm Kreß, circa 1901. Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, TF-005582.

The gasoline-powered floatplane of Wilhelm Kreß on the Wienerwaldsee, Tullnerbach, Austro-Hungarian Empire, circa October 1901. J. Lecornu. La Navigation aérienne : Histoire documentaire et anecdotique. (Paris: Librairie Vuibert, 1913), 321.

Wilhelm Kreß (1836-1913) was a German piano maker who, in 1898, in or near Wien / Vienna, Austro-Hungarian Empire, began to design a gasoline-powered floatplane with three pairs of wings mounted in tandem.

The budding aviator chose to design a seaplane because he could not find a level piece of ground near Vienna. As well he also thought that landing in water would reduce the risk of damaging his aeroplane, an aeroplane which might, I repeat might, have been funded at least in part by Emperor Franz Joseph I, born Franz Joseph Karl of house Habsburg-Lothringen.

Why did a gentleman trained as a piano maker supervise the construction of a large seaplane from the beginning of 1900, you ask, my reading friend? In or near Neulengbach, Austro-Hungarian Empire, you think, not too far from Vienna, actually. A good question. You see, Kreß had been interested in flight since at least 1864. He made and tested several scale models in the 1860 and 1870s, but back to our story.

Even though Kreß’s aeroplane was completed in 1901, its designer very much doubted that it would ever fly. You see, the engine Kreß had bought in the German Empire was much heavier and slightly less powerful than expected. In any event, the seaplane was transported to Tullnerbach, Austro-Hungarian Empire, on the shores of a small lake near Vienna, the Wienerwaldsee. Testing seemingly began in late September.

Incidentally, Kreß’s aeroplane was apparently the first flying machine fitted with a control stick, which meant that the French aviation pioneer / inventor / engineer Robert Esnault-Pelterie did not really invent that device, in 1906.

An artist’s impression of the accident which sank the seaplane of Wilhelm Kreß at the Wienerwaldsee, Tullnerbach, Austro-Hungarian Empire. Anon., “Der Unfall des Ingenieurs Kreß.” Illustrirtes Wiener Extrablatt, 6 October 1901, 1.

Another artist’s impression of the accident which sank the seaplane of Wilhelm Kreß at the Wienerwaldsee, Tullnerbach, Austro-Hungarian Empire. Anon., “Ein verungkückåter Flugversuch des Ingenieurs Kreß.” Wiener Bilder, 9 October 1901, 1.

The first three high speed runs of the seaplane went well, and this even though Kreß had to make a tight turn on every occasion, to avoid running into a dam. During the 4th run, on 3 October, one of the wings touched the water of the Wienerwaldsee. The seaplane capsized, and sank. Kreß was quickly rescued. He was unharmed but arguably lucky to be alive.

The still incomplete second seaplane designed by Wilhelm Kreß, Tullnerbach, Austro-Hungarian Empire. Victor Silberer, “Neues von Kress.” Wiener Luftschiffer-Zeitung, June 1902, 87.

Using the same engine, Kreß set out to build a second floatplane, that one fitted with 4 pairs of wings, in 1902. He eventually ran into money problems linked to the fabric covering of the wings of his flying machine, and to the transfer of future trials to a larger lake, the Neusiedler See. Those issues proved so serious that the project came to stop before the new seaplane could be tested.

A monument to Kreß’s memory was unveiled on the shore of the Wienerwaldsee, in October 1913, less than 8 months after his demise.

Alois Wolfmüller (1864-1948) was a German engineer / inventor who was involved, through a small German firm, Motor-Fahrrad-Fabrik Hildebrand & Wolfmüller, with the development of the first motorcycle in the world to be series produced, in 1894-95.

More interestingly for us today, my reading friend, he also designed an ornithopter whose 3 pairs of wings were mounted in tandem. Powered by a gasoline engine designed by Wolfmüller himself, that aeroplane was seemingly completed no later than December 1901, in München / Munich, German Empire. It proved able to lift off the ground for brief periods of time but proved highly unstable. The Wolfmüller ornithopter never flew.

Johann Hermann Ganswindt, circa 1902. Wikipedia.

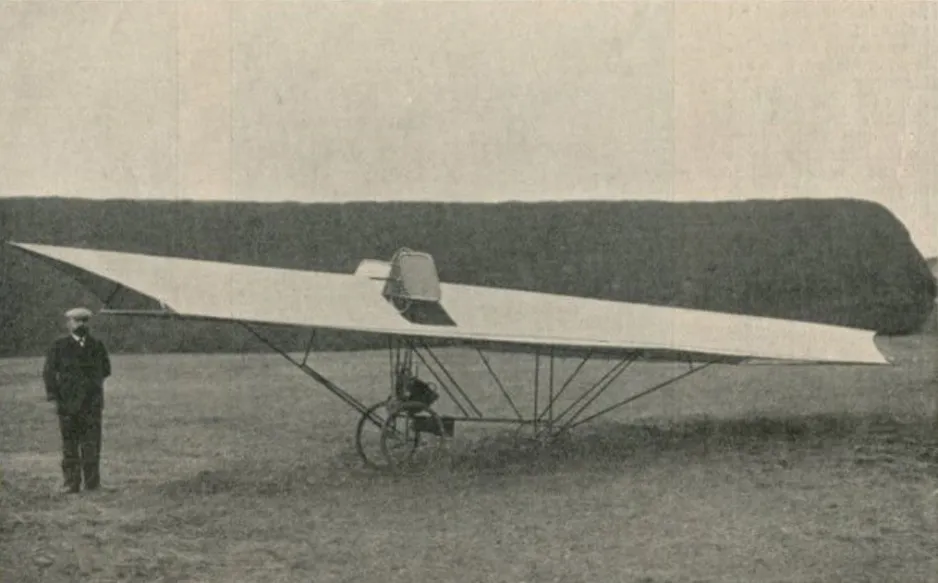

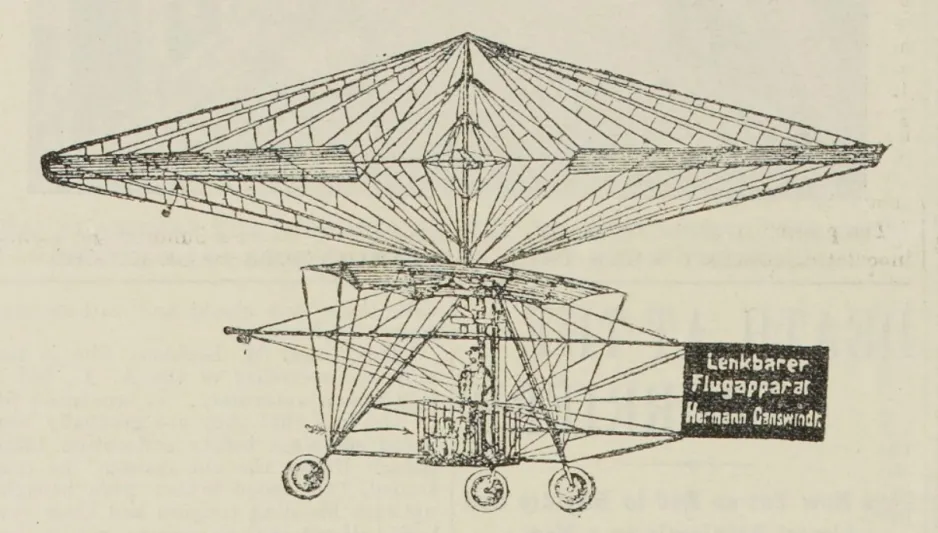

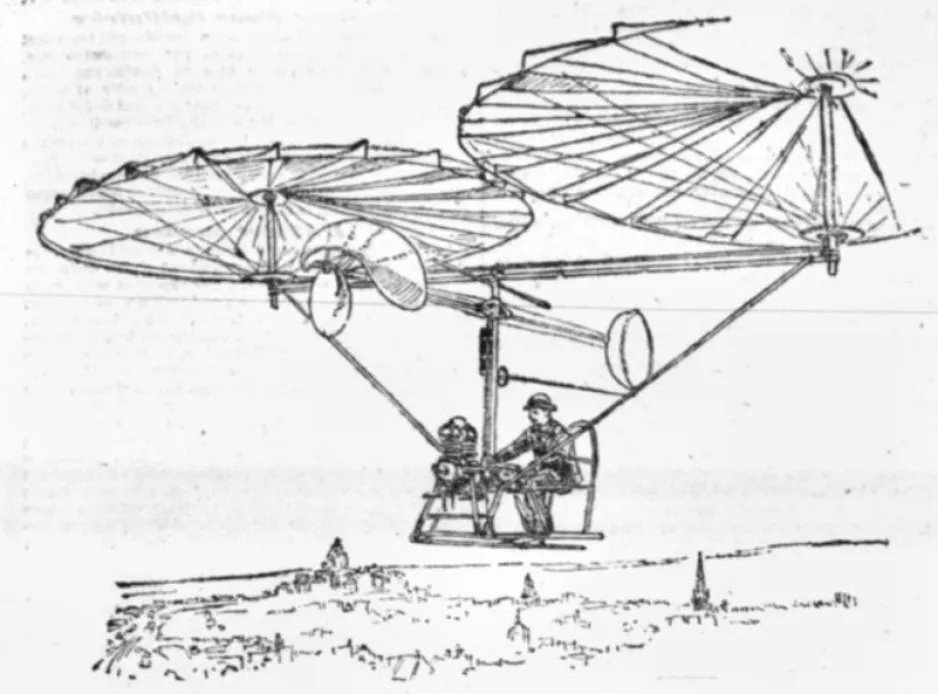

The helicopter designed and built by Johann Hermann Ganswindt, Schöneberg, German Empire. Anon., “New German Air-Ship.” The New York Herald, 30 March 1902, 2nd section, 2.

Johann Hermann Ganswindt (1856-1934) was a brilliant if eccentric German lawyer / inventor who completed a winged helicopter in Schöneberg, near Berlin, German Empire, in the spring of 1902. I think.

Indeed, in October 1901, he had demonstrated to a group of (senior?) officers of the Deutsches Heer, in other words the German army, the lifting capabilities of a test rig fitted with a smaller version of the rotor he had designed. Said test rig proved able to lift a 12-year-old boy off the ground, a feat surpassed by the brief lift off of two adult men.

The engine which drove the rotor remained safely on the ground during that demonstration. I know, I know. I too wish I knew how Ganswindt’s contraption worked. Any thoughts?

In any event, as far as yours truly can figure out, Ganswindt’s winged helicopter was ensconced in a circular workshop, in Schöneberg, located near a smaller circular workshop whose lofty dome allowed the test rig to rise almost 10 metres (30 or so feet) into the air. And yes, a stout cable prevented said test rig from hitting the ground if something went wrong in midair.

Sadly enough, yours truly cannot say if Ganswindt’s helicopter was flight tested. Somehow, I doubt that it was.

You see, Ganswindt was arrested for fraud in mid-April 1902. He had allegedly misled the people who had invested in his projects through a committee set up in March, and this even though he knew that his flying machine would never work. Ganswindt was also accused of using some of the moolah for his own personal benefit.

Ganswindt strongly rejected any allegation of wrongdoing. Fully exonerated by the authorities, he was released in mid-June. By then, however, the committee had gone belly up. Ganswindt was for all intent and purposes broke.

It should be noted that Ganswindt was also a spaceflight enthusiast who, back in 1893, had begun to design a spaceship which, he hoped, would be able to travel over the Earth’s poles, and go as far as Mars or Venus. That Weltenfahrzeug, in English world vehicle, or interplanetary vehicle perhaps, as Ganswindt called it, was to be taken to the upper reaches of the atmosphere by a flying machine of some sort. The explosion of metallic containers filled with dynamite would propel it from that point onward.

Ganswindt’s spaceship ideas were quickly forgotten. They only resurfaced in the 1920s when a number of young German spaceflight enthusiasts began to meet and plan the creation of a society for space travel. The world famous Verein für Raumschiffahrt was founded in June 1927.

The most famous member of that society became a key figure in the American space program. That German individual whose National Socialist past was carefully buried for many years, Wernher Magnus Maximilian von Braun, has been mentioned several / many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since January 2019.

Incidentally, Ganswindt’s idea to use explosive charges to propel a spaceship was not as bonkers as you might think. Nay. Have you heard of a classified / secret American project named Project Orion, my reading friend? No? Now, that is a tale worth telling.

In 1958, the General Atomics Division of General Dynamics Corporation, a well-known American defence giant mentioned many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since March 2018, began to work on the first serious attempt to develop an atomic / nuclear bomb powered rocket. And yes, that was Project Orion.

Would you believe that the idea of using atomic bombs to power a rocket was put forward no later than 1946, by Stanisław Marcin Ulam, a Polish American physicist / mathematician involved in the Manhattan Project, the research and development program which led to the production of the first nuclear weapons, 2 of which ended up being used against Japan in August 1945?

How was an atomic pulse rocket supposed to work, you ask, my slightly nervous reading friend trying to see if there is something in the sky above? Well, (a significant?) part of the energy released by the hundreds of explosions of small atomic bombs ejected out of the base of the rocket would have hit a large and very robust push plate located there. That plate was linked to the rocket by ginormous shock absorbers.

As you may well imagine, designing a pusher plate capable of taking that kind of pounding proved a wee bit difficult. Mind you, designing a crew compartment capable of protecting its precious human cargo also proved a tad difficult.

Why go through all that trouble, you ask? Well, you see, calculations made around 1958-59 showed that an advanced Orion rocket would be able to make a round trip to Mars in… 4 weeks – which was / is a tad shorter than the 19 or so months that a hypothetical 2033 piloted mission would require to make the same round trip. So, 4 weeks or 19 months. Which would you pick?

In 1963, given the underwhelming interest shown by the United States Air Force (USAF), which wanted intercontinental ballistic missiles to attack, dare one add incinerate, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), Project Orion was pretty well dropped in the lap of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), a world-famous American organisation mentioned moult times in our stunning blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since March 2018.

It soon caught the eye of the aforementioned von Braun, who dreamt of launching a piloted mission to Mars. Sadly enough, not too many NASA bigwigs had happy thoughts when Project Orion was mentioned.

You see, the upper management of NASA knew it would have a public relation problem of biblical proportions if an Orion rocket ever experienced a major failure during its journey through the atmosphere. Dozens, if not hundreds of small atomic bombs could rain out of the sky. Although any explosion was unlikely, radioactive material could contaminate areas of unknown size on our big blue marble.

The signing, in August 1963, by the United States, the United Kingdom and the USSR, of the Treaty banning nuclear weapon tests in the upper atmosphere, in outer space and under water, did not help Project Orion’s prospects one tiny bit.

Topping that off, the cost of the Apollo program was increasing rapidly, dare one say exponentially, and there was no way on the Flying Spaghetti Monster’s green Earth that NASA could find moolah to pay for that program and Project Orion.

In December 1964, NASA announced it would not put another penny in Project Orion’s piggybank. Seeing that, the USAF announced it would not put another penny in said piggybank either. Project Orion officially came to an end in the spring of 1965.

Profuse apologies for that demonstration of verbal diarrhea.

Félix Henri Villard. Anon., “An Auto to Run in the Air, Invented by M. Villard.” The New York Herald, 16 November 1902, 2.

The initial version of the vertical takeoff and landing aeroplane / helicopter developed by Félix Henri Villard, Paris, circa 1902. Bibliothèque nationale de France, R36749.

Félix Henri Villard (1869-1916) was a French sculptor / painter who began to build a vertical takeoff and landing aeroplane / helicopter at some point in 1901, presumably in Paris. You might be interested, or not, to hear (read?) that the small engine of that flying machine was to drive its propeller as well as its circular wing.

Incidentally, the presence of that still incomplete flying machine created quite a stir at the Concours (international?) d’appareils d’aviation held in Paris, France, in November 1901. That stir was quite understandable. You see, Villard’s incomplete flying machine was the only piloted powered heavier than air flying machine on display.

That disco-hélicoptère, as its creator called it, was completed at some point in 1902. Yours truly cannot say if Villard attempted some sort of test flight.

Incidentally, again, news reports of the time referred to Villard’s flying machine as an aviateur, in English aviator. The completely different meaning of that word in 2024 is one of the traps that researchers have to keep in mind when conducting research on early aviation back in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The English word air ship / air-ship / airship found in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in countless newspapers, for example, might not refer to a lighter than air flying machine. Nay. It might actually refer to what you and I would call an airplane, or aircraft. Indeed, back then, the English word aeroplane could refer to either a wing or an aeroplane. In turn, the word aerodrome could refer to a flying machine or the place where such things took off and landed.

Another example of a trap might be the use of the French word glisseur / aéro-glisseur in newspaper articles published in Québec until the late 1940s. That word was a translation of the English word glider, in French planeur, but back to our story.

A slightly outlandish artist’s impression of the second version vertical takeoff and landing aeroplane / helicopter developed by Félix Henri Villard in flight. André Rob, “La navigation aérienne.” La Réforme, 21 November 1902, 1.

Villard moved to Belgium in 1902, presumably to Bruxelles / Brussel, possibly after completing his disco-hélicoptère or “automobile aérien,” yes, aérien, not aérienne as a francophone reader would say (type?).

And yes, automobile was a masculine noun in French in 1902. Mind you, automobile was also a feminine noun at that time. The eventual feminisation of the term actually came from the general public.

Indeed, even in 1910, the Académie française, one of the five academies of the Institut de France, aimed at, in translation “giving sure rules to [the French language] and making it pure, eloquent and capable of dealing with the arts and sciences,” preferred un automobile to une automobile.

The masculine choice of that masculine language police was not particularly surprising. The Académie française was an organisation whose misogyny was such that it did not see a woman enter its walls until March 1980, 346 years after its foundation, in 1634. The mind boggles, but I digress.

Another digression if I may. The Académie française did not see an African enter its walls until June 1983. The first Muslim, a woman, might have entered those walls in June 2005.

By early August 1902, in Schaerbeek, Belgium, near, Bruxelles, Villard had completed a flying machine fitted with two circular rotating wings mounted side by side. Villard was at the controls for the first test, in Schaerbeek, during that very month. He was unable to lift off.

That flying machine might, I repeat, might have been on display at the 1903 Salon de l’automobile, du cycle et des sports held in Bruxelles, in March. If so, it would have created quite a stir. You see, Villard’s flying machine would have been the only piloted powered heavier than air flying machine on display.

Would you believe that some of the moolah Villard used to finance his work came from Prince Albert Léopold Clément Marie Meinrad of house… Saxe-Coburg and Gotha?

Yes, yes, my surprised reading friend. The future King Albert Ier of Belgium was the nephew of the future King George V, born George Frederick Ernest Albert of house Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, but I digress, and for the last time today.

Villard built three helicopters in 1913-14, in Belgium, the Ornis 1, 2 and 3. Ornis 2 briefly lifted off, more or less uncontrollably, at least once from June 1913 onward. The onset of the First World War brought the testing of Ornis 3 to a close.

Reverend Burrell Cannon. Frank P. Lockhart, “The Ezekiel Airship.” Houston Daily Post, 20 April 1902, 10.

Reverend Burrell Cannon (1848-1922) was a blacksmith / machinist / sawmill operator who happened to be the pastor of a Baptist Church in Pittsburg, Texas, when, at some point in the mid to late-1890s, he set out to design a gasoline-powered aeroplane driven by a quartet of paddle wheels. He had drawn his inspiration from the Bible’s Book of Ezekiel, Ezekiel / Yəḥezqē’l being a Jewish / Hebrew prophet who had lived in the 6th century before the current era.

And yes, that same biblical book led an Austrian American aeronautical and mechanical engineer, Josef Franz Blumrich, to the conclusion that Ezekiel had experienced a close encounter of the third kind. In other words, the prophet had met extraterrestrial beings who had offered him a ride in a spaceship. I kid you not.

A West German publishing house published Blumrich’s book, Da tat sich der Himmel auf: Die Begegnung des Propheten Ezechiel mit außerirdischer Intelligenz, in 1973. And yes, again, that publishing house was the one which had put on book store shelves, in 1968, a book by Swiss author Erich Anton Paul von Däniken, Erinnerungen an die Zukunft: Ungelöste Rätsel der Vergangenheit, a best seller better known to an anglophone reader under the title of Chariots of the Gods?

As was to be expected, Blumrich’s book was also translated in English. The Spaceships of Ezekiel hit the shelves in 1974.

Incidentally, the titles of the German language books written by Blumrich and von Däniken can be translated as Then the sky opened up: The prophet Ezekiel’s encounter with extraterrestrial intelligence and Memories of the future: Unsolved mysteries of the past.

Interestingly, if only for yours truly, in 1974, Blumrich worked at the… Marshall Space Flight Center of NASA. He left his position, Chief of the Systems Layout Branch, in the fall of that year, but back to our story.

Yours truly hopes that the preceding digression did not prove excessively annoying, and this even though the main theses of those books was, is and will continue to be utterly ludicrous. The people who dwelled upon our big blue marble hundreds if not thousands of years ago did not need the help and assistance of the Great Gonzo to do what they did. Sorry, sorry. Back to our story.

The airship Ezekiel of Reverend Burrell Cannon, Pittsburg, Texas. Anon., “The Airship Ezekiel.” The Aëronautical World, 1 June 1903, 250.

With his plans in hand, Cannon began to build his creation in August 1900. Another version of the story suggested that he contracted out the work to a local firm, presumably around that time or a tad later. The staff of Pittsburg Foundry & Machine Shop soon began to turn said plans into an actual aeroplane.

In any event, Cannon was seemingly the brains behind the engine of his aeroplane. He actually supervised the fabrication of two engines. The first one did not seem to have the oomph necessary to achieve take off.

In any event, again, in June 1901, Cannon and 20 or so leading men from Pittsburg founded Ezekiel Airship Manufacturing Company in order to produce the flying machine in question. The shares were quickly gobbled up by hopeful investors. Indeed, their value seemingly went sky high. No pun intended.

Cannon seriously planned to go to St. Louis, Missouri, where would be held, between April and December 1904, an international exposition / world fair, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, the most stupendous entertainment the world had ever seen, if yours truly may once again paraphrase the ballyhoo of a newspaper headline of the time. If truth be told, he got in touch with fair officials no later than April 1902.

Why the he** did Cannon want to go to St. Louis, you ask? A good question. You see, one of the many attractions of the world fair, besides the Games of the III Olympiad, was an aeronautical competition with a grand prize of no less than $ 100 000. To earn this truly titanic sum of money, which corresponds to about 4 750 000 $ in 2024 Canadian currency, a pilot only needed to go around a 16-kilometre (10 miles) circuit 3 times. Easy peasey.

In late 1902, on a Sunday, when Cannon was busy preaching, some of the workers who had constructed the Ezekiel Airship allegedly decided the time had come to test it. One of them climbed aboard and lifted off the ground. Allegedly. “Gus” Stamps was seemingly doing fine until a fence grew nearer and nearer. He cut the engine and landed. The distance covered during that uncontrolled and unconfirmed, I repeat unconfirmed, hop was 50 or so metres (165 or so feet).

In any event, Cannon and the partly dismantled Ezekiel Airship took a train at Pittsburg in early April 1903. They were on their way to St. Louis – and more test flights. And yes, yours truly realises very well that the Louisiana Purchase Exposition would open more than 12 months later.

Shortly after the train arrived in Texarcana, Texas, by the looks of it, a windstorm blew in. The Ezekiel Airship was thrown off the flatcar it was travelling on and badly damaged.

What happened later on to the crippled aeroplane was / is unclear. An unconfirmed story had it and Cannon completing their journey to St. Louis. The latter allegedly supervised the necessary repair work in order to fly yet again. The Ezekiel airship allegedly took off but failed to clear a telephone pole in its path. Whether or not Cannon was injured in that unconfirmed accident was / is unclear.

Another story stated that Cannon completed a second Ezekiel Airship after his mishap in St. Louis, a machine he took, by train, to Chicago, Illinois. An otherwise unknown individual by the name of Wilder was at the controls for the first flight there, a flight which ended when the aeroplane hit, you guessed it, the top of a telephone pole.

Cannon seemingly tried to finance the construction of a brand-new aeroplane, in Longview, Texas, around 1911. Some say he actually built that machine which, sadly enough, ran into… a telephone pole.

As you may have guessed by now, it is all but impossible to untangle the Gordian knot which prevents researchers from figuring out what Cannon did or did not do.

You may be pleased to hear (read?) that a full-scale replica / reproduction of the Ezekiel Airship completed in 1987 can be admired at the Northeast Texas Rural Heritage Museum, in Pittsburg. There is also a plaque, erected in 1976 in Pittsburg by the Texas Historical Commission

Would you believe that Cannon’s story inspired the creation of a musical, Story of the Century, in 2016, whose texts were written by David Hill, an amateur playwright and professional clinical psychologist born in Texas but living at the time in Kansas City, Kansas? Sadly enough, Story of the Century might never have been played in full on a stage.

And we might want to end this penultimate part of our article at this point in time. After all, you undoubtedly have things to do, as do I.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)