Happy birthday to us. Happy birthday to us. Happy birthday dear CASM. Happy birthday to us: A few words on the early days, weeks, months and years of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum

25 October 2020 is indeed a joyful day, my reading friend. On this day, 60 years ago, the National Aviation Museum, today’s positively and absolutely amazing Canada Aviation and Space Museum, opened its doors to the public.

Yours truly will not keep you busy for long. Nay. Having joined the staff of this august institution, physically if not administratively / hierarchically, in the fall of 1987, I very much intend to celebrate this occasion. In moderation of course.

How had Canada Aviation and Space Museum come to be, you wonder? Well, let me enlighten you.

Would you believe that an Aeronautical Museum was organised in the 1930s, under the auspices of the Associate Committee on Aeronautical Research of the National Research Council (NRC)? That is truly true. Said museum opened had its doors in 1937, in Ottawa, Ontario. Its doors were shut forever soon after the onset of the Second World War, in September 1939.

In 1945, the treasures of the Aeronautical Museum were almost lost forever when someone(s) at NRC suggested that the old engines and stuff be, well, turfed. The head of the Mechanical Engineering division of NRC, John Hamilton Parkin, put his foot down, both of them possibly, and nicpped this idea in the bud.

In 1950, the leader of the federal opposition and former Premier of Ontario, George Alexander Drew, mentioned the idea of recreating a Canadian / national aviation museum during the annual meeting of the Air Industries and Transport Association (AITA), the umbrella organisation which regrouped both Canadian aircraft manufacturing firms and air carriers. Three years later, this question was mentioned yet again. This time around, however, Prime Minister Louis Stephen Saint-Laurent, who was present, indicated he favoured the idea.

The creation of a museum was seemingly mentioned by AITA secretary Arthur George “Tim” Sims, a service manager at Canadair Limited, during another 1954 meeting of AITA. The people present liked the idea and referred it to the group’s information committee so that it could be discussed further at its next meeting, in June. After much discussion, the members of said committee decided to contact the aforementioned Parkin as well as John Joseph Green, another well-known and respected aeronautical engineer who was chief of Division B (aeronautics + armament) of the Defence Research Board (DRB), a federal organisation mentioned several / many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since December 2018. The information committee also approached various groups and organisations to see if they would support the creation of a Canadian / national aviation museum.

Do I need to remind you that Canadair was a subsidiary of the American defence giant, General Dynamics Corporation, 2 firms mentioned… Very good, I will not, and there is no need to get upset.

The end result of the various chats held during the days and weeks after the second AITA meeting was a meeting held in Ottawa in September 1954. The list of attendees was impressive indeed:

- John Russell Baldwin, Deputy Minister, Department of Transport (DOT);

- Andrew George Latta McNaughton, Chairperson of the Permanent Joint Board on Defense;

- R.N. Redmayne, Manager of AITA;

- Air Marshal Charles Roy Slemon, Chief of the Air Staff, Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF);

- Ormond McKillop Solandt, Chairperson of the DRB;

- Edgar William Richard Steacie, President of NRC;

- John Armistead Wilson, Director of Air Service, DOT (retired);

as well as the aforementioned Green and Parkin.

This august assemble, chaired by Slemon, concluded that a national aviation museum located in Ottawa was required. It also concluded that an NRC associate committee should be formed to stickhandle the file.

Even though the formation of the Associate Committee on a National Aviation Museum began in earnest, its members first met only in December 1955. Its membership at the time consisted of the aforementioned Green, McNaughton, Parkin and Sims, by then director of military aircraft sales at Canadair, as well as

- Ernest Adolphe Côté, Deputy Minister, Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources;

- E.R. Hopkins, RCAF Association;

- John Robert Kennedy Main, DOT;

- James Mackintosh Manson, NRC;

- William Philip “Bill” Paris, secretary general / manager of the Royal Canadian Flying Clubs Association;

- Air Vice Marshal John Lawrence Plant, member of the Air Staff, RCAF; and

- G.M. Ross, Air Cadet League of Canada.

At the very first meeting of this group, DOT offered to provide the future museum with some space in the new terminal building at Uplands Airport, near Ottawa, which was good news.

What was not good news was the fact that the 2nd meeting of the associate committee took place in May 1957, soon after Horace Charles Luttman, secretary of the Canadian Aeronautical Institute, joined the group. Somewhat disheartened by the lack of action, Parkin nonetheless presented a brief on the future museum.

Things did not get any better by the time the 3rd meeting of the associate committee took place, in November 1957. You see, DOT informed the group that the space in the new terminal building at Uplands Airport was no longer available. Taken aback, the team wondered if the artifacts collected since the 1930s could be displayed in the terminal buildings of as yet unchosen airports in Canada.

In 1958, a brief on the future aviation museum was presented to Prime Minister John George Diefenbaker, which led nowhere. As you well know, this gentleman was mentioned in an October 2020 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

When the team met for the 4th time, in October 1958, DOT informed it that the space in the new terminal building at Uplands Airport was once again available. An engineer from NRC’s Mechanical Engineering division, Malcolm Sheraton “Mike / Mac” Kuhring, was put in charge of a sub-committee, the Sub-Committee on Space, whose task was to examine the space offered by DOT. Interestingly, the brief to the Prime Minister was not mentioned at the meeting. A possible opening date for the museum, seemingly in 1959, was put on the table.

A memorandum written by McNaughton and Côté may, I repeat may, have been presented to the federal Cabinet in the fall of 1958, or the winter of 1958-59.

In February 1959, at the 5th meeting of the associate committee, the Sub-Committee on Space reported that about 1 200 square metres (about 13 000 square feet) within the terminal building at Uplands Airport would be available, but not given forever and ever, on the 2nd floor of the East wing, as well as some space downstairs, at the front, where a full scale replica of the Silver Dart biplane built in 1908 by the Aerial Experiment Association was to be displayed. The members of the associate committee agreed that, even though the museum was scheduled to open on 1 July 1959, their group should remain in existence, as an advisory body. And no, not every person at the table thought that the museum could really open on 1 July. Indeed, not every person at the table thought that the museum could really open in 1959.

And yes, the Aerial Experiment Association was mentioned many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since October 2018. Now, do I have to point out that the pilot of the Silver Dart performed the first controlled and sustained flight of a powered aeroplane in Canada, but NOT in the British Empire, in February 1909? Great. Thank you.

Any hope of opening the aviation museum in 1959 flew out the proverbial window in early August of that year, as a result of a demonstration flight made at Uplands Airport / RCAF Station Uplands by United States Air Force (USAF) Captain George Leonard Schulstad. You see, my reading friend, the good captain’s Lockheed F-104 Starfighter supersonic fighter aircraft inadvertently exceeded the speed of sound during a low pass. Oops…

100+ glass panels, some of them about 5.5 x 2 metres (about 18 x 6.5 feet), on the almost complete terminal building, scheduled to open in September 1959, were shattered. Would you believe that the ceilings on all 3 floors were damaged?

The building eventually came into use in mid-June 1960, with an official opening late in the month. Schulstad, on the other hand, went on to have a most interesting career in the USAF. He retired as a Brigadier General.

Now, you may ask, why so much damage? A very good question and one which opens the door to an act of pontification on my part.

When an aircraft flies at relatively low speed, the pressures caused by its movement through the air are transmitted in all directions to the surrounding air in the form of waves, known as pressure waves, that travel at the speed of sound, which is a relatively high speed (about 1 225 kilometres/hour (about 760 miles/hour) at sea level and a tad over 1 060 kilometres/hour (just about 660 miles/hour) between 12 and 20 000 metres (39 400 and 65 600 feet) above sea level.

When an aircraft reaches the speed of sound, the sound waves and pressure waves it produces cannot move away from it because both they and the aircraft travel at the same speed. These waves therefore pile up in front of the aircraft and form a huge and yet very thin “wall” of compressed air moving at the speed of sound. In other words, they form a shock wave, a very thin sheet of air, approximately 0.0025 millimetre (0.0001 inch) in thickness, where the pressure, density and temperature of the air increase suddenly, and where the local flow velocity is reduced significantly.

The shock waves bend back and form a shock cone, or Mach cone, if our aircraft exceeds the speed of sound and flies at supersonic speeds. The faster our aircraft flies, the sharper the angle of the shock cone. An (in)famous consequence of this is the sonic boom, or sonic bang, which occurs when the shock waves caused by an aircraft flying at the speed of sound, or faster, reach the ears of people on the ground along the flight path of that aircraft. It can be heard many kilometres (several miles) on either side of this flight path. Incidentally, the pilot, crew and / or passengers of a supersonic aircraft never hear the sonic boom.

Sonic booms come in pairs even though people on the ground do not always hear both. The first one is caused by the shock wave formed at the front of the aircraft. This particular shock wave is called a bow wave. A shock wave known as the tail wave marks the pressure drop which occurs behind the tail. In order to hear both sonic booms separately, the distance between the aircraft and the observers has to be fairly large.

The intensity of a sonic boom is in part proportional to the weight and shape of an aircraft, to the type of ground below, to the meteorological conditions and, especially, to the altitude the aircraft is flying at. Oddly enough, the aircraft’s speed apparently has (very?) little influence on the strength of a sonic boom.

A sonic boom at low altitude can be likened to a giant clap of thunder. It can rattle, or even break, dishes and windows. It can also cause momentary acute discomfort in humans. A supersonic aircraft flying at very high altitude, on the other hand, may create a sonic boom that is barely heard or felt. This explains why low supersonic flight at low altitude over inhabited areas is very much verboten.

Now, you may also ask, what was a USAF supersonic jet fighter doing at Uplands in August 1959? Another good question, my reading friend. You see, the federal government had announced in early July 1959 that the North American / Canadair Sabre daytime jet fighters used by air defence squadrons of the RCAF based in Europe to fulfil Canada’s pledge to the American-dominated North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) would be replaced by Canadian-made Starfighters.

What the federal Cabinet may not have realised at the time, with the exception, perhaps, of Minister of National Defence, George Randolph Pearkes, was that the intended role of these shiny new aircraft, tactical strike, a role sought by many high ranking RCAF officers, meant that these aircraft would be carrying (thermo)nuclear weapons that would be dropped on military installations of member states of the Treaty of friendship, cooperation and mutual assistance, a Soviet-dominated organisation better known as the Warsaw Pact. (Thermo)nuclear weapons were a big thing in the 1950s and many armed forces wanted to be associated with this technology. There was, however, a big catch.

Had a third world war started, Canadian pilots going eastwards to their targets might have come across other pilots, Warsaw Pact pilots, going westward, to their targets, with (thermo)nuclear weapons that would be dropped on military installations of members states of NATO. None of these pilots would have found a safe place to land after their mission. Indeed, the families of all these aviators would have been dead. Mutually… Assured… Destruction. MAD. Home sapiens is a real piece of work, isn’t it?

And yes, the unimaginably good collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum includes a Starfighter, but back to our story and the, err, 6th meeting of the Associate Committee on a National Aviation Museum.

During said meeting, held in November 1959, the aforementioned Kuhring presented a model of the planned layout of the future national aviation museum’s floor.

Kenneth Meredith “Ken” Molson, a fine gentleman mentioned several times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since July 2018, reported for duty as the first curator of the new national museum in July 1960, as did 3 other staff members.

The small team spent the following months developing the displays and interactives proposed by Kuhring. They completed their work in October 1960 – one day before the official opening of the National Aviation Museum, as the new national museum was called. Imagine that, a full day to check, leisurely, if everything was working well. Which was the last museum to accomplish this exploit? (Hello, SB, EG and EP!)

Said displays went over many topics, including the pioneering work made by Wallace Rupert Turnbull, a gentleman mentioned in a March 2019 issue of our you know what, on the development of propellers.

And yes, more than a few items on display at the National Aviation Museum came from NRC.

The aforementioned Diefenbaker was scheduled to officially open the museum, on 25 October 1960, but other engagements prevented him from doing so. He may have been preparing for a 3-day tax sharing meeting with the premiers of Canada’s 10 provinces, scheduled to start on 26 October. The minister responsible for the National Aviation Museum, the very newly minted Minister of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources, Walter Gilbert Dinsdale, was also busy somewhere else. As it turned out, the Minister of Fisheries, John Angus MacLean, a Second World War RCAF veteran, was seemingly the only Cabinet member available to declare the National Aviation Museum officially open.

The original plan for the opening was to have the Prime Minister remotely open the doors of the museum using some sort of push button doodad. The image of the opening was to be captured by closed circuit television cameras for the benefit of people who would be in another area of the terminal building. Did Maclean push the button, you ask, my reading friend? I have no idea.

It should be noted that a number of RCAF aircraft, Avro Canada CF-100 Canuck all weather bomber interceptors to be more precise, presumably based at RCAF Station Uplands, flew over Uplands Airport before, during and / or after the opening ceremony. Other RCAF aircraft were on static display:

- a Canadair Argus maritime patrol aircraft,

- a Convair / Canadair Cosmopolitan transport aircraft,

- a de Havilland Canada Chipmunk basic trainer aircraft,

- a Grumman Albatross search and rescue amphibian aircraft;

- a Lockheed / Canadair Silver Star advanced trainer aircraft,

- a North American / Canadair Sabre daytime fighter aircraft,

- a Piasecki H-21 search and rescue helicopter,

as well as a Canuck.

It looks as if the company-owned prototype of the Canadair CL-41, the ancestor of the CT-114 Tutor trainer aircraft of the RCAF / Canadian Armed Forces / Canadian Forces, was also on static display, as was a de Havilland Canada Beaver bush aircraft owned by Laurentian Air Services Limited of Ottawa – a firm which should not be confused with Laurentide Air Service Limited, Canada’s first bush flying operator, a firm mentioned in September 2019, December 2019 and September 2020 issues of our you know what.

Would you believe that the incredible collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum includes examples of all of these aircraft, with the exception of the Albatross and H-21? And yes, we have a Convair Model 580 rather than a “Cosmopolitician,” as the Cosmopolitan was sometimes called. And your point is?

And yes, you are quite correct, my knowledgeable reading friend, the National Aviation Museum was the only national museum which came under the Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources. All other national museums of Canada fell within the purview of the Secretary of State of Canada. These museums were of course the National Museum of Canada, today’s Canadian Museum of History and Canadian Museum of Nature, the National Gallery of Canada and the Canadian War Museum. Why was this so, you ask? I have no idea.

In any event, the National Aviation Museum came under the purview of the Secretary of State of Canada in 1961. It may have reported to the minister through the head of the National Museum of Canada, but back to October 1960 and the official opening of the museum.

MacLean having performed his opening duties, the aforementioned McNaughton spoke briefly, in front of a replica of the aforementioned Silver Dart. Among the many guests was none other than the lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia, John Alexander Douglas McCurdy a famous Canadian aviation pioneer mentioned many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since September 2017.

You will remember, I hope, that McCurdy was the pilot of the real Silver Dart when this aeroplane performed the first controlled and sustained flight of a powered aeroplane in Canada, in February 1909.

Incidentally, as the very well-known Montréal, Québec, daily newspaper La Presse pointed out in 2 sizeable articles published in December 1960 and January 1961, the terminal building at Uplands Airport, in Ottawa, the airport of the capital city of an officially bilingual country, was quite simply outrageously unilingual. Arrivals and departures were announced in English only. The signs in the shops were in English only. Virtually all official signs and panels in the building were in English only. The sole exceptions were:

- a bilingual sign over an entrance (some? many? most?) travellers had to walk through;

- trilingual signs over the entrance to the water closets (Ladies / Dames / Damas + Men / Hommes / Caballeros); and

- a bilingual sign over the entrance of the National Aviation Museum.

If I may paraphrase the comment made by Jean Rivest, the author of the December 1960 article, the mid December 1959 statement made by the very newly minted Minister of Transport, Quebecker Léon Balcer, to the effect that, endeavouring to respect official bilingualism, this department was an example others could follow, was… a… joke.

Rivest had made a stop at Uplands Airport after flying out of Toronto, Ontario, on his way to Montréal. He had quite been disappointed by the hostility encountered in the Ontario capital when he had tried to make himself understood in French.

Did you know that the author of the January 1961 article, Marcel Gingras, was the editorialist in chief of the Ottawa daily Le Droit between 1964 and 1973? Throughout these years, he was a firm promoter of the right of Franco Ontarians to have access to French language secondary schools, but back to Uplands Airport.

Both Rivest and Gingras were very pleased to note in their texts that every caption / label in the National Aviation Museum was bilingual. The button operated audio recordings located at 10 display cases were also available in both official languages. Sadly, when Rivest visited the museum, 3 of the 10 French language recordings were not working.

Would you believe that the manager of said airport was French, as in French French? Robert Joberty, a technician and pilot who may have served in the Aéronautique militaire of the French Armée de Terre during the First World War, managed 3 Canadian airports during his long career, namely Montréal (Dorval) Airport in Québec, Regina Airport in Saskatchewan and Uplands Airport, although not in that order. As far as yours truly can figure out, this gentleman arrived in Canada no later than 1930.

Do you remember the bilingual sign over an entrance (some? many? most?) travellers had to walk through, my reading friend? Who do you think had to battle indifference if not downright hostility in order to obtain that one sign? Joberty, of course. Worse still, after asking for permanent bilingual signs to replace the temporary unilingual ones used at the time of the opening of the terminal building, Joberty, the manager of the airport, let us remember, was simply ignored.

Incidentally, in 1961, the average Anglophone male worker from Québec, either unilingual or bilingual, earned almost twice as much, 1.9 times actually, as the average Francophone male worker from Québec, either bilingual or unilingual.

Given this context and the big thaw which followed the victory of the stupendous team led by Jean Lesage in the June 1960 general election in Québec, after the long and depressing Duplessian darkness, was it surprising that the first fairly successful political organisation dedicated to the promotion of Québec independence, the Rassemblement pour l’indépendance nationale, was formed in Montréal in September 1960?

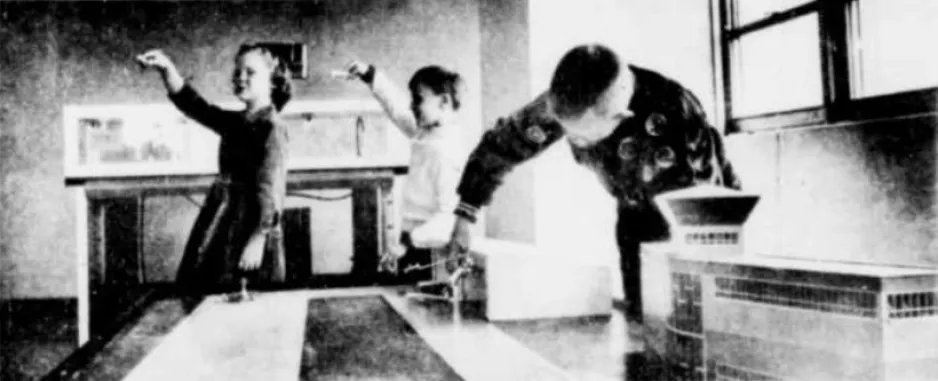

Anyway, as more and more visitors began to appear at the doors of the National Aviation Museum, Molson and his staff quickly realised that the museum’s interactives had not been designed to resist the rough treatment meted to them by said visitors. A lot of time was spent human-proofing said interactives.

Gorillas in the making? Françoise Côté, “L’aéronef devient objet de musée.” Le Soleil – Perspectives, 4 March 1961, 23.

A view inside the National Aviation Museum, Uplands Airport, Ottawa, Ontario, late 1960 or very early 1961. Please note the indentation toward the front of the float. The imprint of a tired gorilla’s rear end, maybe? CASM, negative number 4154.

Yours truly has been known to suggest in recent years that interactives should be designed as if they were to be used by angry gorillas, no offense to gorillas, which appear to be far more peaceful hominids than their Home sapiens cousins, and I do stand by these words. I have used them in front of other museum professionals on several occasions, including some from Japan, and got nods of understanding on every occasion. And yes, we are hominids. Mind you, we are also mammals, like the platypus, Parma wallaby and New Caledonian flying fox. Long live Charles Robert Darwin – and Alfred Russel Wallace! Evolution is a fact.

Three of the young visitors of the National Aviation Museum interacting with the miniature airport contained therein. Françoise Côté, “L’aéronef devient objet de musée.” Le Soleil – Perspectives, 4 March 1961, 23.

Incidentally, one of the museum interactives in question was a miniature airport, with a terminal building and control tower, a hangar, and models of airliners in the colours of Trans-Canada Air Lines and of its arch rival, Canadian Pacific Airlines Limited, a subsidiary of transportation giant Canadian Pacific Railway Company. Right beside it was a window people of all ages could look through to better appreciate the level of activity at Uplands Airport. It looks as if the National Aviation Museum had a dedicated children’s area.

I do wonder if many 1960 aviation museum across the globe was as interactive or as inviting as the one in Ottawa. Just sayin’.

One of the display cases of the National Aviation Museum, Uplands Airport, Ottawa, Ontario, early 1960s. It provided information on the first nonstop airplane crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, in June 1919, between Newfoundland and Ireland. CASM, negative number 6875.

Besides its armour plating of interactives, the museum’s staff also developed new displays and interactives during the months which followed the opening. It also cleaned up / restored several aircraft engines. Under the guidance of the aforementioned Molson, the museum began to build up a photograph collection, and a library containing books, magazines, manuals, etc. Aircraft models built by expert firms at a standard scale (1:24) were acquired as well.

If I may be permitted to type a few words on the library project launched by Molson, I must say that the work done was not in vain. Yours truly is of the opinion that the fabulous library of the equally fabulous Canada Aviation and Space Museum is the best publicly accessible aeronautical library in Canada. Its initial core came out of donations made by the Institute of Aeronautical Sciences, in the United States, and, even more so perhaps, the acquisition of the library of an Austrian organisation, the Österreichischer Flugtechnischer Verein, which was a direct descendant of the Austro-Hungarian Wiener Flugtechnischer Verein, one of the oldest (1880) aeronautical association on planet Earth.

Mind you, the photograph collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum is also very good indeed. This being said (typed), one must admit that its holdings for the period between 1960 and 2020 could use a bit of a boost.

Virtually all of the pre 1960 photographs were / are black and white images. The lack of colour illustrations dating from the early days of Canadian aviation led to the production of a series of paintings by an artist by the name of Robert William Bradford, a fine gentleman mentioned several times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since February 2018.

The production of paintings, as well as the creation of new displays and interactives, and possibly other things as well, pretty well came to a stop in 1967 when the National Aviation Museum became a creature of the newly created National Museum of Science and Technology (NMST), today’s Canada Science and Technology Museum, but we are getting ahead of our story.

A view of the annex of the National Aviation Museum, Uplands Airport, Ottawa, circa 1963. CASM, negative number 4565.

As the river of time flowed passed the door of the National Aviation Museum, its premises went through a growth spurt in 1963, when it was allowed to take over the entire display area on the ground floor of the terminal building at Uplands Airport. The space in the Museum Annex, as this area became known, could house 4 aircraft and several engines.

By then, things were afoot that would forever change the National Aviation Museum. You see, the growing collection of aircraft of this institution was not only one in Canada. Nay. The Canadian War Museum had a few historic aircraft and the RCAF had a lot more. The former did not have much space for aircraft and the latter had no permanent facility to display its holdings.

Informed around 1963 that the annual temporary presentation of historic aircraft at RCAF Station Mountain View, Ontario, near Trenton, was becoming an irritant, Wing Commander Philip de Lacey “Phil” Markham, a fine gentleman who was interested in these aircraft and their preservation, put forward an idea which garnered a great deal of interest. The RCAF’s collection of historic aircraft should be moved to RCAF Station Rockcliffe, Ontario, near Ottawa, which would no longer be used as air base from 1964 onward. Wing Commander Ralph Viril Manning, RCAF Air Historian, another fine gentleman who was also interested in the historic aircraft and their preservation, took on the file.

With its 40+ year history as an air base, not to mention its landplane and seaplane facilities, RCAF Station Rockcliffe was as a most appropriate location for a national aviation museum.

While progress proved slow, Markham obtained a green light to display the RCAF’s collection of historic aircraft in Second World War era wooden hangars at RCAF Station Rockcliffe during the spring of 1964.

In parallel to this, the Department of National Defence and the Secretary of State of Canada agreed to display at RCAF Station Rockcliffe all the aircraft under their purviews, in other words those of the Canadian War Museum, National Aviation Museum and RCAF – with the exception of those already on permanent display in the 2 museums. This agreement would see the management of all 3 collections take place under one roof.

Visitors who paid a visit to RCAF Station Rockcliffe in June 1964, on Air Force Day, were surprised and delighted by the number of machines on display. Those who paid a visit to the site until the fall, when the display season ended, were equally surprised and delighted.

In May 1965, the hangars containing the National Aeronautical Collection (NAC), as the merged collections were to be called from then on, officially opened to the public. A gentleman mentioned in a December 2018 issue of our you know what, the minister of National Defence, Paul Theodore Hellyer, officiated the ceremony

Personnel from National Aviation Museum and the Canadian War Museum took care of aircraft maintenance and daily housekeeping. And yes, the National Aviation Museum continued to exist as a separate entity as this was taking place.

As cooperative as the institutions involved in the NAC (Canadian War Museum, National Aviation Museum and RCAF) may have been, the truth was that the arrangement under which the unified collection operated was awkward.

During a meeting in June 1965 with Richard Gilchrist Glover, director of the Human History Branch of the National Museum of Canada, to whom the Canadian War Museum and National Aviation Museum reported, the director of the Historical Section of the Canadian Armed Forces pretty much said so. Charles Perry Stacey added that a single entity should be responsible for the NAC. He was of the opinion that the National Museum of Canada should be that entity, but this was only his personal opinion.

Weeks turned months without any change to the arrangement under which the NAC operated. This being said (typed?), discussions were afoot in Ottawa regarding the creation of a national museum of science and technology which was to report to the Secretary of State of Canada. Indeed, a teacher / photographer / geologist / explorer, David McCurdy Baird, was appointed director of this national museum of Canada, in the fall of 1966. The National Aviation Museum was assigned to this new national museum.

The National Aviation Museum displays and interactives located in the terminal building at Uplands Airport went to the soon to be opened NMST in the spring of 1967, which pretty much led to the de facto disappearance of the national museum founded in 1960. “Temporarily” located in a repurposed bakery, NMST officially opened its doors to the multitude in November 1967.

The aforementioned Molson retired in September 1967. The equally aforementioned Bradford then became the curator of the NAC.

Back in December 1966, Baird had contacted the Under Secretary of State to see if something could be done regarding the arrangement under which the NAC would operate in the future. G.G. Ernest “Ernie” Steele set up a meeting which brought together Baird, Glover and representatives of multiple organisations, namely the Canadian War Museum, the National Aviation Museum and the Department of National Defence.

At some point after the meeting, Steele contacted the Department of National Defence. The NAC was a great success, he said. Indeed, given Canada’s great contribution to the development of aviation, Steele believed that the holdings of the federal government should be displayed in the best manner possible. He therefore suggested that the NAC be placed under the direction of NMST.

Steele’s proposal did not go unnoticed. These were some within the RCAF and / or the Department of National Defence who opposed the idea of displaying their collection of historic military aircraft besides civilian aircraft and technical exhibits / interactives. It was suggested that the National Aviation Museum be responsible for said civilian aircraft and technical exhibits / interactives while a new air force museum at RCAF Station Rockcliffe would have the collection of historic military aircraft. Indeed, it looks as if the idea of an air force museum had been in the air, no pun intended, since early 1960 at the latest.

For some reason or other, these voices went unheard. The NAC was placed under NMST in 1968. This being said (typed?), the Canadian War Museum would be able to display a few aircraft if it chose to do so. In turn, NMST would be able to display a few NAC aircraft if it chose to do so.

At the risk of overstepping the boundaries of good taste, may I suggest that the National Aviation Museum of 1960-67 at Uplands was a far more interesting place, for non-aviation enthusiast at least, than the NAC / National Aviation Museum of Rockcliffe of 1965-88?

When the aforementioned Baird retired, in late 1981, the equally aforementioned Bradford became Acting Director of NMST.

The NAC became the National Aviation Museum in September 1982. The plan at the time was to turn this subsidiary museum of NMST into an independent national museum.

When physicist James William “Bill” McGowan was appointed Director of National Museum of Science and Technology, in January 1984, Bradford was promoted to the position of Associate Director of the National Aviation Museum. At the same time, he acquired complete control over most of the museum’s activities. This, again, was linked to the planned transformation of the National Aviation Museum into an independent national museum. That never happened.

In June 1988, after 20+ years spent in flammable old hangars, the National Aviation Museum officially moved into a brand new, purpose designed facility. This national institution became the Canada Aviation Museum in 2000. A storage hangar completed in 2006 led to the creation of new display areas in the main museum building, which were set up between September and November 2008. The Canada Aviation Museum inaugurated an auditorium, a foyer, an improved cafeteria, an improved gift shop, as well as classrooms in the fall of 2010. By then, it had changed name yet again, having become the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in April.

Kenneth Meredith Molson left this world in January 1996, at the age of 79. Robert William Bradford is still with us, however. He will be 97 years old in December 2020. Would you believe that this gentleman of gentleman, one of the most famous Canadian aviation artists ever, was born on 17 December 1923, 20 years to the day after the first controlled and sustained flight of a powered aeroplane? It’s a small, small world.

As was said (typed?) at the beginning of this article, yours truly joined the staff of what was then the National Aviation Museum, physically if not administratively / hierarchically, in the fall of 1987. Since then, I have crossed the path of many remarkable individuals, in other words museum staff members, museum volunteers and a number of museum group staff members closely associated with the crazy folks at the aviation museum. Sadly enough, many of them are no longer with us.

Given that October is Women History Month, I would like to put on paper in a very personal manner the names of the many fine people who have played a role in the evolution of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, and this even though I know, old fogey that I am, that I will forget more than a few…

Anna Adamek

Sylvie Ayotte

Heather Bajdik

Nancy Beaulieu

Suzanne Beauvais

Sylvie Bertrand

Shelley Boudreau

Linda Brand

Lisa Burbidge

Gisèle Cyr

Claire De Grasse

Gillian Desnoyers

Victoria Dickenson

Suzanne Dumont

Linda Dupuis

Catherine Émond

Dorothy Fields

Chantal Fortier

Rachelle Fournier

Roxanne Gatien

Bianca Gendreau

Lorraine Gouin

Nori Gowan

Louise Gratton

Erin Gregory

Christina Harb

Annie Jacques

Hayley Jones

Sian Jones

Andrée Joyce

Karoline Klug

Glenda Krusberg

Gail Lacombe

Claudia Larouche

Suzanne Lévesque

Zoe Lomer

Christina Lucas

Kathleen McCullough

Molly McCullough

Deidre McEwen

Sonia Mendes

Dominique Mongeon

Rachel Monnier

Marcia Mordfield

Francine Poirier

Erin Poulton

Renée Racicot

Erika Range

Kimberly Reynolds

Maxime Sabourin

Claudette Saint-Hilaire

Erin Secord

Kate Shouldice

Fiona Smith-Hale

Lynda Smyth

Tanya Sulatyski

Sandra Taillefer

Linda Talbot

Andréanne Tessier

Christina Tessier

Adele Torrance

Audrey Vermette

Lise Villeneuve

Stacy Wakeford

Sue Warren

Lynn Wilson

Please do not hesitate to rattle my cage if I missed you or someone you know and, by the way, does anyone know the first name of the young woman by the name of Telford who was the executive assistant of the National Aviation Museum in the early 1960s?

This writer wishes to thank all the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, not theirs.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)