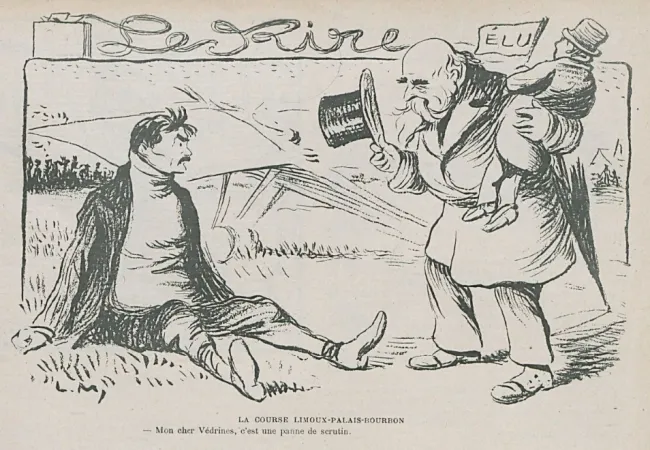

“My dear Védrines, it is a voting failure:” Charles Toussaint “Jules” Védrines and the partial legislative election of Limoux, France, in March 1912, Part 1

And you already have a question, my reading friend? That was fast, not that I mind of course. If I may paraphrase the inveterate British inventor Wallace, ooh, but yours truly does like a bit of pontification.

In what way and why was senator Henri Charles Étienne Dujardin-Beaumetz gently messing with Charles Toussaint “Jules” Védrines, the defeated candidate in the Limoux, France, by-election of March 1912? Well, that is a long story and you should know by now how yours truly loves long and convoluted stories. And yes, it is indeed too late to take back your question. Bwa ha ha. Sorry.

Incidentally, the words spoken by Dujardin-Beaumetz, in translation and entirely fictitious of course, were not lacking in humour: “My dear Védrines, it is a voting failure.” The little character the senator was carrying on his shoulder was the candidate / puppet chosen by him to replace him as representative for the electoral district of Limoux, in the south of France, Jean Bonnail, but I am jumping (flying?) ahead of myself.

So, let us start at the beginning. Who was / is Védrines? Born in December 1881 into a working-class family, our friend began working as a teenager in Paris, France, as a roofer, with his father and brothers, then as a plumber. Anxious to improve himself, Védrines took evening classes at the Institut Catholique des Arts et Métiers, in Lille, near the Belgian border.

In 1908, obsessed like so many others by the exploits of the first aviators, that young man with a strong, if not to say (type?) almost volcanic, personality had only one desire: to fly. However, he did not realise that dream right away. Nay. Suffering from a lack of dough, he practised a few trades more and more related to aviation. Védrines, for example, became an excellent aeroplane engine mechanic. In fact, his talent led him to be hired, in 1910, by an extravagant and well-known British actor fascinated by aviation, Robert Bilcliffe Loraine. An innate pilot, Védrines was awarded a license in December 1910. A brilliant career began.

Védrines’ first feat was undoubtedly his victory in one of the most famous aeronautical events of the time, the Paris-Madrid race of May 1911. In fact, he was the only pilot to cross the finish line. Védrines also won third place in the Circuit européen d’aviation, held in June and July, in Belgium, France, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, as well as second place in an air rally, the Circuit of Britain, held in July and August. Védrines was then employed by the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Morane-Borel-Saulnier.

Does that name, or part of that name, ring a bell, my reading friend? It should. Yes, yes, it should. Sigh. Manufactured in 1911 by the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Borel, the Borel-Morane monoplane at the fantabulastic Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, is the oldest aircraft still in existence which has flown on Canadian soil, but back to our story.

In August 1911, a glazier and great Italian patriot whose employer had a contract with the Musée du Louvre in Paris stole a relatively well-known but small, an important detail here, Italian painting. Vincenzo Peruggia quietly returned to his Paris hovel with… the Mona Lisa by Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci. Yes, yes, the Mona Lisa. At the Musée du Louvre, there was panic, especially since some employees knew that this canvas was not the first artifact to have disappeared.

Would you believe that a young Spanish painter and a French critic / poet / writer of Polish origin, Pablo Ruiz Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire, born Guillaume Albert Vladimir Alexandre Apollinaire de Kostrowitzky, or Wilhelm Apolinary Kostrowicki, or…, were suspected of the theft? Indeed, both were guilty of fencing. They had in their hands ancient Iberian statuettes from the Musée du Louvre stolen by Apollinaire’s female secretary. A judge released Picasso and Apollinaire, however. And yes, the statuettes were obviously returned to the museum, but back to our story once again.

As you may imagine, the under-secretary of state for Fine Arts, you guessed it, Dujardin-Beaumetz, himself a painter, got republicanally told off both inside and outside the Chambre des députés, which sat at the Palais Bourbon, the name mentioned in the title of the drawing published by Le Rire, a popular French illustrated humorous weekly.

This being said (typed?), our man still had in his pocket a lot of people from his constituency of Limoux. His position as under-secretary of state for Fine Arts had indeed allowed him to exercise the subtle art of patronage.

It should also be noted that Dujardin-Beaumetz had a somewhat particular conception of his role as representative. Indeed, during the campaign preceding the legislative election of 1910, that Parisian born in Paris allegedly declared in utter seriousness that, regardless of the popular will, he would be a representative because such was his good pleasure. Wow. Incidentally, Dujardin-Beaumetz was quick to leave the premises at top speed, through a back door, to avoid the slaps of outraged citizens. Mind you, he was probably saying out loud what many politicians mumbled, mumble and will continue to mumble under their breath. Sorry. Sorry.

Realising that his days as the representative for Limoux might be numbered, Dujardin-Beaumetz began to ogle very seriously and enviously the comfortable seats of the Sénat, that of France of course, even if, in fact, the seats of the Senate of Canada were / are probably just as comfortable. Sorry. Sorry.

And yes, patronage and various other subterfuges might have influenced the delegates composing the electoral college which gave its confidence to Dujardin-Beaumetz during the partial senatorial election held in January 1912.

Suddenly, the seat of representative of the electoral district of Limoux, occupied until then by the new senator, needed a new occupying posterior. Dujardin-Beaumetz’s gaze quickly turned away from the intended candidate to settle on the owner of a drapery factory in the region. Not very interested in politics, the aforementioned Bonnail nevertheless ended up agreeing to stand as a candidate in a by-election to be held on 17 March. With the imperious support of Dujardin-Beaumetz who saw in him a puppet he could control as he pleased, Bonnail’s victory seemed assured. In fact, no serious candidate was running against him.

Who would dare to go against the will of Dujardin-Beaumetz and the heads of the regional administration, appointed by the government, who, as was often the case then, supported the official candidates, and this despite instructions of neutrality? Indeed, who would dare?

On 10 March, Védrines was in a town in the vicinity of Limoux. He was participating in one of the countless flights, often sponsored by municipalities, which had taken place all over France since August 1909, the month during which the Grande Semaine d’Aviation de la Champagne, the world’s first airshow, had taken place.

Indeed, the municipal council of Limoux voted a small sum of money intended for Védrines in order to convince him to go there with an aeroplane. While that project fell through, the aviator nevertheless went to said vicinity town. Unfortunately, he damaged his aeroplane when he landed, after a (second?) flight much appreciated by those present, including many Limouxines and Limouxins.

Carried away by the enthusiasm of the crowd present at the event, that son of a Parisian worker, dare I say that proletarian, with political opinions leaning towards the left, but a patriot all the same, launched into politics as an independent socialist and national defense candidate for the post of representative for Limoux. He hoped, it seemed, to promote aviation and military aviation in the Chambre des députés. Védrines also wanted the French government to launch a national subscription which would make it possible to buy many military aeroplanes. And yes, you were right, my reading friend with your eyes wide shut, the ballot was to take place on 17 March.

A meeting with the mayor of a nearby city, the physicist and left-wing socialist Ernest Joseph Antoine “Lo Pelut” Ferroul, a man revered for his defense of the region’s winegrowers during their revolt in 1907, a popular movement suppressed / “pacified” by soldiers who killed at least 6 unarmed demonstrators, may have played a role in Védrines’ decision to enter politics. And yes, France had Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité as its motto then and still today.

While Védrines did not run under the banner of the Section française de l’Internationale ouvrière, he may very well have sung a few times and very loudly these words of the anthem of that party, the French socialist party, L’Internationale:

L’état comprime (opprime?) et la loi triche. L’impôt saigne le malheureux. Nul devoir ne s’impose au riche. Le droit du pauvre est un mot creux.

The state squeezes (oppresses?) and the law cheats. Tax bills bleed the miserable. No duty is imposed on the rich. Rights of the poor is an empty word.

And yes, these words date from 1887. Dare I say they remain just as true in 2022? (Hello, Mr. “Big Brother!”)

Informed by Védrines of his wish to enter politics, the mayor of Limoux initially believed it was a joke – a feeling shared by some Parisian elites. Realising that the aviator was serious, Pierre Constans-Pouzols may, I repeat may, have tried to make him change his mind. He indeed realised very well that offering an opponent of the caliber of Védrines to a parachuted and bland candidate like Bonnail, an unknown candidate at best and an unpopular one at worst, would not please Dujardin-Beaumetz, the municipal council and the heads of the regional administration. Indeed, some of those heads were reluctant to accept the candidacy of Védrines, reluctantly approved on 12 March.

Even the main daily newspaper in the region, La Dépêche, quickly ceased to sing the praises of the heroic pilot that was Védrines and began to attack him.

Védrines categorically refused to give up his idea, even if, according to Lady Rumour, the most important party in the Chambre des députés, the Parti républicain, radical et radical-socialiste, promised for all intents and purposes to give a seat of representative in the Paris region to that mule if he agreed not to play the spoilsports in Limoux. And yes, Dujardin-Beaumetz was a representative of that party.

Initially grounded by his somewhat rough landing, you do remember that rough landing, do you not, Védrines began his campaign by automobile. His many supporters were quick to improvise songs to well-known tunes. In at least one of them, Dujardin-Beaumetz and Bonnail were given the, uh, amusing but rude nicknames, Jocond 1er and Jocond II, inspired by the theft of the Mona Lisa, in French La Joconde, and, perhaps, by the French from France slang word “con,” which means cretin or imbecile.

The use of the expression French from France was important. Indeed, many people, if not the majority of the people, living in the south of France in 1912 understood and / or spoke a Romance language other than French, to the chagrin of successive (nearly 60 between September 1870 and the start of the First World War!) governments in Paris, governments whose linguicide policies were not new. That language, well threatened in 2022, was / is Occitan.

Fa un freg de can! Bufarà tot duèi; òm fotriá pas un can defòra!

Il fait un froid de chien! Ça va souffler tout aujourd’hui; on ne mettrait pas un chien dehors!

It is freezing cold! It is going to blow all of today; one would not put a dog outside!

Védrines was apparently back in the air on 13 March. He then made a flight promised 3 days earlier to the good people of Limoux. He did it again the next day, flying over villages and landing in Limoux as well as in the municipality where Bonnail’s factory was located. Védrines and his aeroplane formed a stupendous team. During these visits, crowds flocked to cheer the candidate aviator. Indeed, Védrines was acclaimed wherever he went. In the camp of Joco… Sorry. In the camp of Dujardin-Beaumetz and Bonnail, there was concern. Could the official candidate lose to a candidate chosen by the… people? Yuk. What an outrage!

On 14 March, Védrines invited his main opponent to participate in a public and contradictory meeting, in Limoux. Bonnail, quiet and reserved by nature, accepted without enthusiasm. On 15 March, Védrines arrived by aeroplane. He spoke first, while journalists from Paris, some of whom were said to represent foreign dailies, wrote down his words. The speech of Védrines, who said he was ready to give up his representative’s allowance and hire Bonnail to help him, excited the imposing crowd which had invaded the main square of the city.

Bonnail, moved, inexperienced and nervous, tried to have himself replaced by the mayor of a neighbouring municipality. The crowd would have none of it. It jeered at Léon Castel who had to retreat. Knowing well what awaited him, Bonnail began to speak. Many in the crowd may have shouted him down. In any event, the official candidate quickly stopped talking.

Carried in triumph, Védrines spoke again. He then returned to the field where his aeroplane was and flew over Limoux once again.

Dujardin-Beaumetz was furious, especially as residents gathered on a terrace, angered by his scowl, had booed him enthusiastically earlier in the day.

On 16 March, Bonnail and Védrines campaigned. The latter seemed to have the wind in his sails. In the camp of Dujardin-Beaumetz and Bonnail, concern mounted.

And it is on this cliff hanger that yours truly concludes this first part of the article on the by-election of March 1912.

Goodbye, see you next week. Adieu, a la setmana que ven!

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)