A century of agricultural technology and innovation in the Laurentides region of Québec: From Dion & Frère to Dion-AG

Hey friend, say friend, come on over, my reading friend, how d’ya like to see some big threshers? Said threshers are in fact stored in the Collections Conservation Centre located within spitting distance of the Canada Science and Technology Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario – a sister / brother institution of the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum, in Ottawa – and of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in… Ottawa.

What is a thresher, you ask? A good question. A thresher is an agricultural machine used to thresh cereals, wheat for example, in order to separate the grains from their envelope (husk) and stem (straw). For many years, this machine has been combined with a harvester. The agricultural machine resulting from this union was / is a combine harvester. (Duh…)

A factoid if you don’t mind. The 1978 song Thrasher of Canadian author / singer / songwriter Neil Percival Young compares the action of a thresher to the natural forces which separate friends from one another.

The first threshers, stationary machines at that time, appeared in Canada, the British colony which gave birth to Québec and Ontario in 1867, when present-day Canada was born, as early as the 1840s. It goes without saying that these machines were much more numerous in their country of origin, the United States. Introduced in the 1820s, stationary threshers were gradually replaced by animal-drawn threshers from the 1860s onward.

The first threshing machine manufacturer in the greater region of Montréal, Canada East, now in Québec, was founded in 1845 at the latest in Terrebonne, Canada East, also today in Québec. The agricultural machinery produced in its workshops was renowned throughout North America, and even in France. Would you believe that Matthew Moody & Sons Company Limited still existed as of 2020, in another form of course? The divisions that exist today are owned by Inox Tech Canada Incorporée of Sainte-Catherine, Québec, and its subsidiary, Systèmes Accessair Incorporée.

Yours truly was surprised to discover that Systèmes Accessair has held since 2000 the rights to manufacture the Plane-Mate mobile lounge or passenger transfer vehicle, a vehicle used at the Montreal Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport to transfer passengers from a terminal building to their airliner. Would you like to know more about this passenger transfer vehicle?

If so, may I suggest that you be patient, my reading friend? I am indeed considering pontificating on this issue towards the end of 2021. You are heartbroken, I know, but, to quote a character of the 1987 romantic comedy and cult movie The Princess Bride, mentioned in some issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since February 2018, get used to disappointment.

Anxious not to affect your morale too much, I am pleased to inform you that 2 of the pioneers of the agricultural machinery industry in Québec were among the first francophone millionaires in North America.

You will of course remember that another of these Croesus was named Antoine Chabot. Better known as Anthony Chabot, this businessman, entrepreneur and philanthropist oversaw the construction of public water systems in California, and other states. This work was so well known that it earned him the nickname “Water King.” Chabot was mentioned in May and July 2019 issues of our you know what.

Incidentally, a brother of my maternal grandfather’s great-great-great-grandfather was / is apparently the ancestor of this wealthy Québec American. Small world, isn’t it? But back to the 2 aforementioned pioneers of the agricultural machinery industry in Québec.

Charles Séraphin Rodier started his business in 1851. By 1880, he was the largest landowner in the greater Montréal area. Charles Alfred Roy, also known as Desjardins, for his part, founded a firm, Compagnie Desjardins (Enregistrée?), in Saint-Jean-de-Kamouraska, Canada East, now in Québec, in 1865. Industries Desjardins Limited still existed as of 2020.

Several other manufacturers of agricultural machinery were created in Québec towards the end of the 19th century or the beginning of the 20th century. These said manufacturers manufactured threshers, among other things.

As you can imagine, an agricultural magazine like Le Bulletin des agriculteurs, a Québec monthly launched in February 1918, mentioned this type of machine more than once over the decades. Would you believe that this publication, then weekly, was simply a revised version of the Bulletin de la Société coopérative agricole des fromagers de Québec, launched in February 1916?

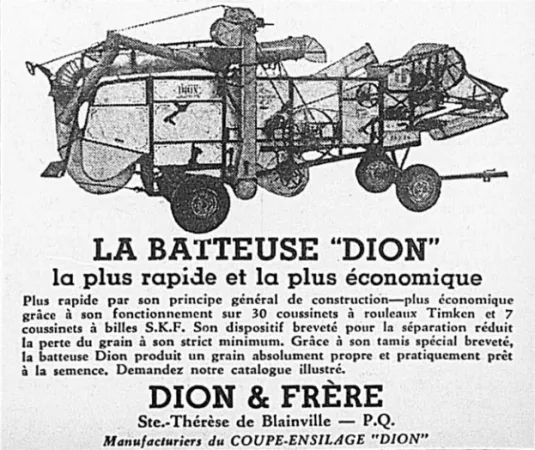

Would you like to know more about, if not the Dion thresher, at least about Dion & Frère Incorporée of Sainte-Thérèse-de-Blainville, Québec? Wunderbar.

Once upon a time, around 1915, there were 2 brothers, Amédée Dion and Bruno Dion, who devoted themselves to general agriculture and the breeding of Jersey cows, in Sainte-Thérèse-de-Blainville. The first was about 35 years old and the second, about 26.

Around 1915, say I, the Dion brothers began to take an interest in the mechanisation of agricultural work. They designed an automatic feed table to feed sheaves of grain into the heart of various types of threshers. If their invention worked well, the Dions realised fairly quickly that their production would only become profitable if their automatic feed table was suitable for threshers whose mechanism was fed from below, not from above - threshers of a type used in the vast expanses of the provinces of Western Canada for example.

In 1918, concerned with meeting the growing needs of their farm, the Dion brothers designed a high-performance thresher made of wood, the material commonly used at the time. As said farm was not designed to meet the needs of people who wanted to manufacture agricultural machinery in relatively large numbers, the number of threshers produced was limited to say the least. Worse still, all the parts of the Dion threshers were made by hand, by the 2 brothers or in small machine shops in the region. Tested in 1918-20, these threshers proved to be tough and reliable.

Realising that their threshing machine was an original, higher-performance machine which produced cleaner grain, and without loss, than contemporary machines, the Dion brothers obtained Canadian and American patents.

In 1920, the Dion brothers founded Dion & Frère (Enregistrée?), on the site of their farm. More and more farmers recognising the quality of its thresher, Dion & Frère had to increase the surface area of its workshops several times over the years. Would you believe that the firm first exported a thresher to the United States in 1926?

Indeed, neither the limited financial resources of the firm, nor the start of the Great Depression, in 1929, prevented Dion & Frère from launching a brand new model of all-metal thresher. This bold but risky initiative paid off. It allowed Dion & Frère to break into the Canadian and American markets. The firm thus manufactured several thousand threshers which were found in many provinces and states.

The Dion brothers also developed a machine which cut the fodder intended for silage. This forage harvester, or ensilage cutter, was not the first of its kind, however. Did you know that a Scottish businessman, inventor and landowner, Sir Charles Henry Augustus Frederick Lockhart Ross, developed such a machine, an example of which was made in the United States in 1925? An American agricultural engineering professor who saw this forage harvester before its trip to Scotland, Floyd Waldo Duffee, set out to improve its concept. He contacted an American firm which manufactured a prototype. For one reason or another, the first production version of the Fox River Tractor Company forage harvester did not appear until 1936. This firm did not mention anywhere the role played by Ross and / or Duffee.

And if Ross’ name means something to you, my reading friend, it is because this gentleman was / is linked to a painful episode in Canada’s participation in the First World War. A great fan of shooting before the Flying Spaghetti Monster, Ross designed a very precise rifle. Series produced by the Ross Rifle Company of Québec, Québec, the Ross rifle became for all intents and purposes the standard weapon of the Canadian Militia around 1911 – much to the chagrin of the British Army which wanted to see the Dominions (Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa) adopt a British rifle, manufactured under license or not in said Dominions.

Unfortunately, the Ross rifle turned out to be totally unsuited to the appalling conditions on the battlefields in France and Belgium in 1915-16. Many Canadian and British senior officers demanded that the Ross rifle be replaced by the standard British Army rifle, less precise perhaps but far more robust. In Canada, the Minister of Militia and Defence, Samuel “Sam” Hughes, a great defender of the Canadian weapon, refused to comply. Increasingly exasperated by the past and present stunts of his fiery tempered minister, Prime Minister Sir Robert Laird Borden forced him to resign in November 1916.

Withdrawn from service in disgrace, thousands if not tens of thousands of Ross rifles were shelved. A machinist from Richmond, Québec, Joseph Alphonse Huot, conceived the idea of transforming these weapons into automatic rifles / light machine guns – an increasingly indispensable type of weapon for trench warfare that the Canadian Expeditionary Force had great difficulty in getting. A prototype of the Huot automatic rifle was put to the test in November 1916. As promising as it was, this weapon seemingly did not have many influential supporters.

An improved prototype arrived in the United Kingdom in January 1918. Tested in March under realistic conditions, the Huot automatic rifle proved to be, by and large, superior to the Lewis automatic rifle, the standard weapon of this type for the armies of the British Empire and one of the most important automatic rifles of the 20th century – which was saying a lot. The Armistice was signed, however, in November 1918, before the conversion of a few thousand Ross rifles began, in the workshops of Dominion Rifle Factory, a crown corporation created out of the very buildings and tools of Ross Rifle, but back to our story.

And yes, before I forget it, please note that the collection of the aforementioned Canada Agriculture and Food Museum, includes 2 ensilage cutter designed and manufactured by the equally aforementioned Matthew Moody & Sons. Said collection also includes a stationary thresher designed and manufactured by Compagnie Desjardins Limitée, a name adopted by Compagnie Desjardins in 1901.

In April 1944, Dion & Frère became Dion Frères Incorporée. The people mentioned in the firm’s letters patent were, uh, no, no more Amédée Dion than Bruno Dion. Said people were François Dion, machinist; Lucien Dion, engineer; and Paul Dion, accountant. Yours truly presumes that these 3 people were sons of Amédée and / or Bruno Dion.

Confident of the potential of Dion Frères, a few investors gave it their support. This support proved invaluable during the construction of a foundry in 1946 at the firm’s site.

Amédée Dion died in 1951, at the age of 70. Bruno Dion left this world in September 1952. He was barely 62 years old. This double twist of fate shook Dion Frères but did not shake its foundations.

In fact, in 1953, after consultation with agricultural colleges and experimental farms, the management of the firm created a research centre where a few engineers and industrial designers worked.

The products offered by Dion Frères also diversified over the years, from farm wagons to precast concrete silos, including at least one automatic feed system for farm animals.

In 1970-71, the North American farm machinery industry was going through tough times. Dion Frères asked a large creditor for a little time. The bank in question refused to grant it a delay. Dion Frères found itself in bankruptcy in July 1971, much to the chagrin of its management – and of many people in the region.

Fearing that they would no longer be able to obtain spare parts and / or find replacement equipment, a number of farmers in the Laurentides region attempted to revive the firm in the late winter of 1971-72. This Comité provisoire Dion Frères Incorporée did not, however, achieve its objective.

During the summer of 1972, B. and R. Choinière Limitée, a firm perhaps created for this purpose by 2 brothers, Bernard and Richard Choinière, acquired the assets of Dion Frères. Dion Machineries Limitée was born. In fact, these firms existed in parallel for many years.

B. and R. Choinière and Dion Machineries did very well over the years. One only need to think about the computerised feeding system marketed in 1988 which could handle a herd of up to 500 cows. This Distronic won the gold medal from the Association des fabricants de matériel agricole du Québec at the 1990 edition of the International Salon of Farm Machinery held in March in Montreal.

In the spring of 2001, Dion Machineries signed an agreement with AGCO Corporation under which this American agricultural machinery giant would distribute some of its products throughout North America, except in Québec and, it seems, Atlantic Canada (New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island).

A change of corporate name from Dion Machineries to DFE Incorporée, DFE meaning Développement d’équipement fourrage, seemed to take place a little later. Regardless, Dion-AG Incorporée was founded in October 2004.

Yours truly servant wonders if the presence of the letters AG in this new corporate name means that AGCO partially controls the Québec firm. Just sayin’.

May I note that Bernard Choinière passed away in October 2009, at the age of 87? Richard Choinière, on the other hand, left this world in March 2018. He is 91 years old.

Directed just as before by members of the Choinière family, Dion-AG still existed as of in 2020. Its factory, located on the site of the 1920 Dion & Frère factory, is located today within the city of Boisbriand, Québec.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)