A prolific Belgian “bande dessinée” author who deserves to be better known: The father of Dan Cooper, Canadian hero, Albert Weinberg (1922-2011), Part 1

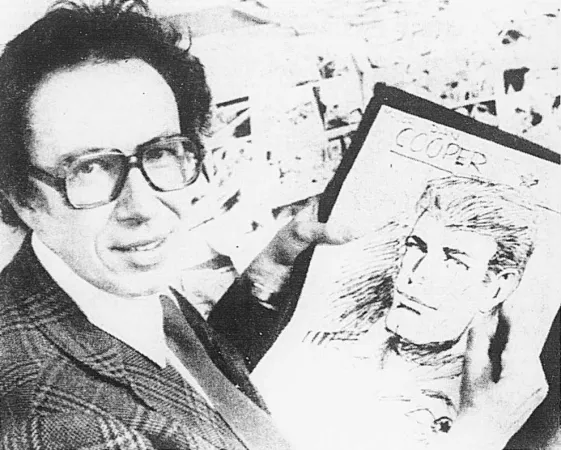

If you do not mind, my reading friend, I would like to talk to you today about a prolific Belgian “bande dessinée” author who deserves to be better known, a gentleman of gentlemen that yours truly met in September 1994, at the Canada Aviation Museum, today’s Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, during an evening surrounding a temporary and traveling exhibition which highlighted the best-known element of his work. (Hello, MD and SD!) I am doing this because Albert Weinberg was born in April 1922, almost a century ago to this day, in Liège, Belgium.

Weinberg initially turned to the legal profession, a field where he studied civil and commercial law, studies interrupted by the Second World War and the occupation of Belgium by National Socialist Germany. During his compulsory military service after peace returned, Weinberg impressed his regimental friends with the quality of his sketches. Indeed, in 1947, his interest in “bande dessinée” led him to become an assistant to the Belgian “bande dessinée” artist Victor Hubinon, one of the great names in 20th century aeronautical “bande dessinée.” Both then worked for World Press, a Belgian “bande dessinée” distribution agency founded by Belgian businessman Georges Troisfontaines.

Was Weinberg an autodidact when it came to “bande dessinée?” Yes, he was.

Weinberg lent a hand to Hubinon for at least one of the adventures of two young boys and great friends, who were not aviators, let us be clear, Blondin, white and serious, and Cirage, black and adventurous. And no, Blondin was not the real hero of that “bande dessinée” published in the illustrated weekly Petits Belges, then in the illustrated weekly Spirou, as well as in the form of albums, 10 in all, published between 1942 and 1956. And yes, a black “bande dessinée” hero was really unusual at the time.

Weinberg also helped Hubinon with the war “bande dessinée” Tarawa: Atoll sanglant, originally published between October 1948 and November 1949 in the Belgian illustrated weekly Le Moustique. That violent, well-documented but strongly manichean story told how American troops managed, in November 1943, to capture, at the cost of heavy losses, the atoll of Tarawa, in the Gilbert Islands, then occupied by Japanese troops who were simply obliterated.

Would you believe that Hubinon lent his features to one of the fictional journalists present in the story? He did the same for his scriptwriter, the Belgian Jean-Michel Charlier, one of the great scriptwriters of Francophone “bande dessinée” of the 20th century, as well as for Weinberg. The latter lent his features to Tim Barkley, a journalist with curly hair.

Weinberg also lent a hand to Hubinon for the “bande dessinée” Joë la Tornade, whose eponymous hero was an American detective pilot, or vice versa, who liked to use his fists. Indeed, Weinberg seemingly drew and scripted two-thirds of that story published in 1947-48 in the Belgian illustrated weekly Bimbo, a story in which his name appeared nowhere. In all honesty, one had to admit that the names of Hubinon and his scriptwriter, Charlier, did not appear either. Fearing to incur the wrath of Spirou’s management, the latter pair imagined a pseudonym, Charvick, to sign that work.

Weinberg also apparently lent a hand to a young Belgian cartoonist and scriptwriter with great promise for the future. Willy Maltaite, better known by the pen name of Will, was indeed working at that time on his first story, Le Mystère de Bambochal, self-published in 1950.

Eventually, though not necessarily chronologically, that work indeed beginning as early as 1947, it seemed, Weinberg lent a hand to Hubinon for at least two of the first adventures of a certain Buck Danny.

In 1947, in Belgium, Charlier, Hubinon and Troisfontaines created an aeronautical “bande dessinée,” Buck Danny, for Spirou. Busy with his business, Troisfontaines quickly withdrew, however. Charlier then took care of the scripts and, for a few years, of certain aspects of the drawings.

American military pilots during the Second World War, Danny and his friends returned to service in 1951, during the Korean War. Their allegiance, United States Navy or United States Air Force (USAF), was unclear for several years. This being said (typed?), the artwork of Buck Danny, a classic in aeronautical “bande dessinée,” constantly improved and achieved pinpoint accuracy.

Hubinon toiled on Buck Danny until his death in January 1979, at the age of 54. A talented artist and journalist specialising in aeronautics, the Frenchman Francis Bergèse, then took up the torch in collaboration with Charlier. It should be noted that Bergèse, Charlier and Hubinon were private pilots. Responsible for the scenarios after the death of Charlier, in July 1989, at the age of 64, Bergèse gave way to a new duo whose first album came off the presses in 2013.

No less than 20 million copies (!) of the 58 albums (!) detailing the adventures of Buck Danny appeared between 1948 and 2020 (!). Barely 3 or 4 were translated into English, which was / is a shame, but I digress. Let us get back to the main character of this issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Between 1949 and 1956, Weinberg produced moult illustrations for various magazines. He also created at least 3 “bandes dessinées” for Héroïc-Albums, a very important Belgian illustrated weekly at that time. Yours truly must admit that he does not know under which profession to place Richard Deville. This being said (typed?), the eponymous hero of Luc Condor was an adventurer / archaeologist who haunted South America while the equally eponymous hero of Roc Météor was an interplanetary / interstellar adventurer. All three were equally fearless and reproachless.

It was apparently at the request of the famous Belgian “bande dessinée” author Paul Cuvelier that Weinberg collaborated, anonymously it must be admitted, on a story published in 1949-50 in the famous Belgian illustrated weekly Tintin, Spirou’s great rival, Corentin chez les peaux-rouges. That story related the adventures of a French teenager on American soil just before the middle of the 19th century.

Between 1952 and 1955, Weinberg also drew (anonymously?) the covers of three albums of the French version published in Belgium of a classic western “bande dessinée,” Red Ryder, created in the United States in 1938. Anonymity might have been useful in that case, given the fact that Spirou published adventures of the eponymous hero of that “bande dessinée” on an episodic basis between 1939 and 1951 approximately.

It was at the bottom of the ladder that Weinberg joined the Tintin team at the beginning of 1950. One of the first major projects on which he worked was to submit ideas for gags or situations that would allow the artistic director of the magazine, Georges Prosper Remi, known as Hergé, to improve the scenario of a story on which that giant of 20th century “bandes dessinées” had been working with more or less success since 1947. That story, the first pages of which appeared in Tintin in March 1950, was one of the most important and impressive adventures lived by the hero created by Hergé. That Tintin adventure, say I, was Objectif Lune, in English Destination Moon.

Weinberg suggested certain readings to Hergé, at least one of which contained works by a well-known American artist / designer / illustrator, one of the fathers of astronomical / space art, Chesley Knight Bonestell, Junior.

According to some, it was to Weinberg that we owe a secondary but crucial character of Objectif Lune and of the second part of Tintin’s lunar adventure, On a marché sur la Lune, in English Explorers on the Moon, the engineer Frank Wolff, who, because of large gambling debts, became a spy in the pay of an unidentified foreign power.

Would you believe that the character of Wolff may, I repeat may, have been partly inspired by a very real person? Emil Julius Klaus Fuchs was a German-British physicist who voluntarily provided important, secret information to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) as he helped develop the first nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Arrested in the United Kingdom in February 1950, Fuchs was sentenced to 14 years in prison – the maximum sentence in his case. That dreadful person was released in June 1959, for good behaviour, and immediately emigrated to East Germany, where he became one of the mainstays of the scientific community in that paradise of the proletariat. Fuchs kicked the bucket in January 1988, at the age of 76.

You do not think that Fuchs inspired Wolff, do you, my skeptical reading friend? Very well. So, let me point out that, in German, the words “wolf,” with a single f, and “fuchs” mean respectively wolf and… fox, but back to our story.

Weinberg also appear to have drawn several elements of a work by Edgard Félix Pierre Jacobs, a giant of Belgian “bande dessinée” better known as Edgar P. Jacobs. The work in question was one of the best adventures of one of the great teams of paper heroes of francophone “bande dessinée,” the Britons Francis Blake and Philip Mortimer, respectively head of the British domestic counter-intelligence and security agency, MI5, and nuclear physicist. The title of the adventure in question? Le Mystère de la Grande Pyramide, in English The Mystery of the Great Pyramid, obviously. That story was originally published in Tintin, between March 1950 and May 1952.

In 1962, Weinberg created a new “bande dessinée.” Les aventures extraordinaires d’Alain Landier, the latter being a doctor, ethnologist and explorer fascinated by vanished civilisations, allowed him to express his interest in various types of so-called Fortean phenomena. About 20 rather short stories (about 4 pages each) appeared in Tintin between 1962 and 1971.

In 1969-70, Tintin published a “bande dessinée,” Giovanni di Celli, where Weinberg recounted the adventures and misadventures of an (Italian?) pilot against a background of espionage. That ephemeral work seemed to have been published initially, in 1969, in an Italian illustrated magazine, Corriere dei Piccoli.

Let us also mention that the Belgian daily newspaper Le Soir published 6 stories of underwater adventures linked to espionage created by Weinberg in 1970-71. Les Aquanautes thus appeared daily for more than 450 days. That “bande dessinée” was not the first work by Weinberg to appear in Le Soir, however. Nay. Between 1955 and 1969, the artist produced around 20 short humorous stories, collectively known as Le Vicomte, recounting the misadventures of an unidentified… viscount.

And yes, my insightful reading friend, Weinberg seemed to have a strong interest in espionage. That was hardly surprising. After all, his career began at the beginning of a crucial period of the 20th century, the Cold War. (Hello, EG and EP!)

All this being said (typed?), it was for something quite different that Weinberg became famous throughout the world. You will learn more about that something next week.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)