A great Canadian success story you should know about: A brief look at the National Research Council of Canada flight impact simulators donated to the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, Part 3

Greetings, my faithful reading friend. Yours truly is indeed happy that you agreed to join me in our examination of the second flight impact simulator of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, a national museum located in Ottawa, Ontario.

That impressive device was put together by Fairey Canada Limited of Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Although not a major player in the Canadian aircraft industry, that firm was one of the major players in Atlantic Canada and British Columbia during the 1950s and 1960s.

Fairey Aviation Company of Canada Limited came into existence in November 1948, at Eastern Passage, Nova Scotia, near Halifax. That subsidiary of the British aircraft maker Fairey Aviation Limited, itself a subsidiary of Fairey Company Limited, was created primarily to deal with the maintenance, overhaul and repair of aircraft operated by the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN).

And yes, the amazing collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum includes two such aircraft, a Hawker Sea Fury single seat fighter and an un-restored Fairey Firefly two-seat fighter.

In the summer of 1950, Fairey Aviation Company of Canada began to convert a number of war surplus Grumman TBM Avenger torpedo bombers into anti-submarine aircraft that the RCN would use on its aircraft carrier, HMCS Magnificent. By 1954, it had become responsible for any and all modifications made to these aircraft until their removal from service. As the 1950s came to a close, the firm began to convert a dozen or so Avengers into civilian spraying aircraft used primarily over insect-infested forests.

In the summer of 1951, Fairey Aviation Company of Canada began to convert some Canadian-made Avro Lancaster heavy bombers of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) into long range navigation training aircraft. That project also grew significantly. By the mid-1950s, the firm was involved with the conversion of more Lancasters to fill new functions, including maritime patrol / reconnaissance and photographic mapping / reconnaissance. In the late 1950s, it also converted a Lancaster into a drone carrier capable of dropping a pair of Ryan KDA Firebee jet-powered target drones.

By 1953-54, Fairey Aviation Company of Canada had received a sub-contract from A.V. Roe Canada Limited (Avro Canada) to produce components of its Avro Canada CF-100 Canuck jet-powered all weather bomber interceptor ordered by the RCAF. Need I tell you how often Avro Canada was mentioned in our you know what? Often since March 2018, you say, my reading friend? Very good. Get yourself a gold star.

One, not two.

As the RCAF prepared to receive the first of its new American Lockheed P2V Neptune maritime patrol / reconnaissance aircraft, in 1955, Fairey Aviation Company of Canada won the contract to maintain / modify / modernise them. The firm also got the contract to produce components of the Canadian-designed and -made Canadair CP-107 Argus maritime patrol / reconnaissance aircraft, which went into service in 1958. It looked as if it also did some maintenance, repair and overhaul work on Second World War vintage Canadian-made Consolidated Canso search and rescue amphibians operated by the RCAF.

Work for the RCN continued at a steady pace, however. Fairey Aviation Company of Canada was responsible for the modification of helicopters it operated, for example – machines like the Bell HTL, Piasecki HUP and Sikorsky HO4S. It also won the maintenance, repair and overhaul contracts for that service’s McDonnell F2H Banshee carrier-based all weather jet fighter, not to mention its North American Harvard training aircraft.

As the 1950s came to a close, the firm modified the Banshees in order for them to carry air to air missiles, in that case Naval Ordnance Test Station AAM-N-7 Sidewinders – a first for the Canadian armed forces.

The Grumman CS2F Tracker carrier-based anti-submarine aircraft, made under license in Canada and put in service in 1957 aboard the aircraft carrier HMCS Bonaventure, was also maintained, overhauled, repaired and, eventually, modernised by Fairey Aviation Company of Canada. In the late 1960s, the firm also modernised a number of Trackers operated by the Koninklijke Marine, in other words the navy of the Netherlands.

Yours truly would be remiss if I did not point out that the admirable collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum includes an Argus, a Banshee, a Canso, an HO4S, an HTL, a HUP, a Lancaster and a Tracker. And yes, it also includes a Firebee, two Harvards and a partridge in a pear tree. Sorry, sorry.

You thought I had forgotten to mention that presence within said collection, did you not? Yes, yes, you did, but back to Fairey Aviation Company of Canada.

Things were going were well indeed for that firm. In March 1955, it opened a new factory at Patricia Bay airport, near Sidney, British Columbia. Besides the usual maintenance, repair and overhaul work on military aircraft, that facility did a lot of maintenance and repair work on civilian machines both large and small. It was there, for example, that some Martin JRM Mars transport flying boats of the Unites States Navy were converted around 1960-64 into water bombers operated in Canada by Forest Industries Flying Tankers Limited of Vancouver, British Columbia.

In 1960, the firm opened a large facility at Halifax’s newly inaugurated international airport. It was there that RCAF’s fleet of Arguses was extensively modernised during the 1960s, for example. Light aircraft and their engines were also serviced and overhauled at the new facility.

Fairey Aviation Company of Canada was heavily involved in the design and development of a highly innovative haul down system which allowed anti-submarine helicopters to be hauled down and quickly secured on the aft deck of relatively small warships (frigates or destroyers) in any weather condition, to a point, day or night. That work was conducted in close collaboration with the RCN.

A prototype of the device, colloquially known as the Beartrap, was installed on a ship, the destroyer escort HMCS Assiniboine, in late summer or early fall of 1963. Sea trials began in November. There were numerous problems and delays, as was to be expected with such a new approach, but the concept proved successful.

The Helicopter Hauldown Rapid Securing Device (HHRSD), as the device became known, was put in production and mounted on a number of Canadian warships where it was used in conjunction with the Sikorsky CHSS-2 / CH-124 Sea King ship-based anti-submarine helicopter. It was adopted by the United States Navy, the Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force (Kaijyo Jieitai) and the West German Navy (Marine), as well as by the United States Coast Guard.

And yes, there is indeed a Sea King in the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

If truth be told, the HHRSD and its successors, initially developed by Dominion Aluminum Fabricating Limited of Mississauga, Ontario, a firm later known as DAF Indal Limited, then as Indal Technologies Limited, are among the most important and original contributions made by Canada in the field of anti-submarine warfare. Indal Technologies has exported systems to at least a dozen navies, including the United States Navy, for examples.

The American firm Curtiss-Wright Corporation acquired Indal Technologies in 2005. The latter still existed as of 2022 and operated as a business unit within the Electro-Mechanical Systems Division of Curtiss-Wright, but back to Fairey Aviation Company of Canada.

Incidentally, that firm became Fairey Canada around September 1964. Working in conjunction with the RCN, it refurbished or restored a pair of carrier-based naval aircraft which now belong to the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, a Sea Fury, in 1964, and a Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber, in 1965.

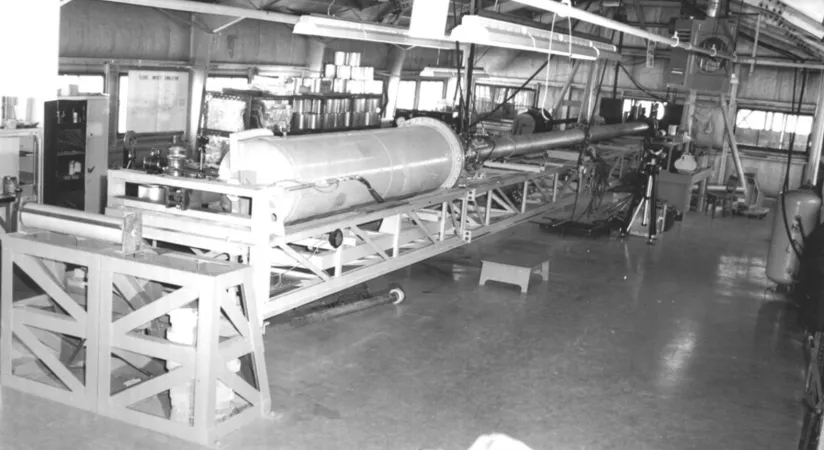

In 1967, Fairey Canada built Canada’s second fully operational flight impact simulator in its facilities near Halifax. That device was later delivered to the National Aeronautical Establishment (NAE), an independent division of the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) based in Ottawa.

Fairey Canada ceased all activities in March 1970. Some time later, a number of managing people based in Nova Scotia won a contract to carry on with the work the firm was doing. Industrial Marine Products Limited (IMP) of Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, gave them some funding. Thus was born IMP Aerospace Limited. The new entity took over the firm’s facilities at Halifax International Airport. It was the second of many such acquisitions by the IMP group.

Over the years, IMP Aerospace worked on numerous airplanes and helicopters operated by the Canadian armed forces. It also obtained foreign contracts.

Two types of aircraft that IMP Aerospace worked on are in the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, namely the Canadair CT-114 Tutor training aircraft and the aforementioned Sea King.

IMP Aerospace remains in operation as we speak (type?), under the name IMP Aerospace and Defence (Limited?), but back to our flight impact simulator, a story you had been (im)patiently been waiting for.

Built by Fairey Canada for the NAE, Canada’s second fully operational flight impact simulator was / is both powerful and large (about 21.5 metres (about 70 feet 6 inches) in length).

To some extent, that device was based on an earlier flight impact simulator operated by the Royal Aircraft Establishment in England. It had a 12.2-metre (40 feet) long barrel with a 254-millimetre (10 inches) bore, and could be taken apart for storage or transport. The 10-inch gun could fire fully feathered 1.8-kilogramme (4 pounds) birds at speeds of up to 1 395 kilometres/hour (865 miles/hour).

The original idea behind the 10-inch gun was that Canada’s main aircraft makers, Canadair Limited and de Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited (DHC), would bring that flight impact simulator to their factories, in Cartierville, Québec, and Downsview, Ontario, to conduct their tests. The various parties realised early on, however, that the proper operation of that device required a great deal of expertise and support equipment. As a result, the flight impact simulator was permanently located at Uplands, near Ottawa, within an organisation known as the Flight Impact Simulator Facility. The creation of that facility took place before the mid-70s.

Canadair and DHC have been mentioned many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee, since November 2017 and February 2018.

The 10-inch gun was actually designed to fire fully feathered birds weighing up to 6.3 kilogrammes (14 pounds). The thinking of the government and industry committee which came up with the specification for the device, NRC’s Associate Committee on Bird Hazards to Aircraft, was that regulatory authorities in Canada and abroad might decide to protect airliners and their engines against birds the size of a Canada goose.

Given a later decision by regulatory authorities to use 1.8-kilogramme (4 pounds) and, later, 3.6-kilogramme (8 pounds), birds as standards against which aircraft and engines would be tested, the fully feathered birds fired by the 10-inch gun did not exceed these sizes.

These birds were common domestic fowl from one or more local farms that were taken to Uplands, euthanised, put in cotton bags and frozen. They were taken out of the freezer 24 hours before testing, so they could completely thaw. The core temperature of each bird was sometimes measured to prove to customers that it was not in the least frozen.

That particular aspect of the process has been / is the butt of countless jokes in which the inexperienced operators of a “chicken cannon” destroyed carefully designed aeroengines, high-speed trains windshields, etc. Totally baffled, these operators contacted experts to see what was wrong. As you may have guessed by now, the experts listened patiently before making a simple comment or asking an equally simple question, which turned out to be the punch line of the joke: the fully feathered birds should be thawed prior to firing.

This being said (typed?), some fascinating, if somewhat disgusting stories have been told about flight impact simulators which appear to be true.

Oddly enough, even though the 3.5-inch gun spent many years at Uplands, the device used to fire fully feathered 450- and 900-gramme (1 and 2 pounds) birds was the much larger 10-inch gun. Mind you, it also fired other types of objects. Although able to fire either synthetic or real birds, the 10-inch gun fired relatively few of the former. It was the opinion of its crew that none of the synthetic birds developed over the years in Canada and elsewhere could duplicate the damage caused by the real thing.

Synthetic birds were used for speed calibration and sabot development only. This being said (typed?), many thought that the use of a synthetic bird turned the clean up of the test area into a somewhat less unpleasant exercise. As it dried, however, the content of early synthetic birds left small razor-sharp projections on the target. These posed a greater threat to personnel than exposure to bird remains ever did.

Incidentally, the word snarge is used to describe what is left of a bird after it strikes an aircraft or target. (Hello, EP!) I hear (read?) that this word is a subtle blend of the words snot and garbage. Bon appétit, everyone. Sorry.

The basic operating principle of the 10-inch gun is identical to that of the 3.75- / 3.5-in gun. Indeed, the two devices shared a common control panel. The target was mounted on a large concrete apron in the open air or, from 1970 onward, on the floor of an enclosed test room with controllable temperature (- 40 to + 54.5 degrees Celsius / - 40 to + 130 degrees Fahrenheit). There was a semicircular dirt embankment outside the firing area to contain any stray material.

And yes, the 10-inch gun was kept in a building at all times.

Interestingly enough, the original idea was to use an actual aircraft as the target. The work involved in towing such a large object from the airport to the test area, not to mention the possibility of damaging it to such an extent that it could not fly out, led to a decision to use components (nose section, wing or tailplane / tail assembly) as targets.

By the way, when the 10-ich gun entered service, the projectile chamber was sealed by tightening by hand 16 (!) one-inch diameter bolts – a tiring and time-consuming process. In late 1971, staff members installed a hydraulic system which used a quartet of high-pressure aileron actuators left from the very well known Avro CF-105 Arrow supersonic bomber interceptor program, a Canadian program of course.

The number of competing companies which used the 10-inch gun is worthy of note. Indeed, that flight impact simulator was one of the few on this Earth which worked for any firm based in a country friendly to the United States and its friends / allies. For a fee, I presume. The reasons for that were simple. It was part of a government facility with a permanent staff. Aircraft or engine makers which might have built a flight impact simulator for their own use used them so infrequently that much was forgotten between each series of tests.

The 10-inch gun was used on a regular basis by a small crew at the Structures and Materials Laboratory of the aforementioned NAE between the late summer of 1968, when it was commissioned, and 1985. More than 2 600 test firings were made during that period, at an average rate of about 13 per month. Actual rates of fire during test programs could be much higher, of course: 55 over 4.5 days in one instance and 13 in one day in another.

The crew of the flight impact simulator conducted windshield and tailplane / tail assembly tests on well-known Canadian aircraft like the Canadair / Bombardier Challenger business jet, the de Havilland Canada DHC-5 Buffalo military transport plane, as well as the de Havilland Canada Dash 7 and Dash 8 turboprop commuter airliners.

As we both know, the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum includes a Challenger, a very important prototype actually, and the prototype of the Dash 7.

The 10-inch gun was also used to test the windshields of well known foreign airliners, business aircraft and helicopters. You may very well have flown aboard some of the foreign airliners in question, aircraft like the Airbus A300, the Boeing 747, 757, 767 and 777, and the McDonnell Douglas DC-9, DC-10 and MD-80.

Over the years, possibly both before and after 1985, bird impact tests were also conducted for a variety of well known military aircraft used by Canada and the United States.

The collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum includes a number of aircraft types linked to the 10-inch gun:

- the aforementioned Tutor,

- the aforementioned Dash 7,

- the Lockheed CC-130 Hercules military transport plane, and

- the aforementioned DC-9.

The 10-inch gun was also used to check the resistance to impact of flight data recorders and cockpit voice recorders. Mind you, it was also used to test the wing structure of the world famous Bombardier CRJ regional jet. The very size of the 10-inch gun gave it a versatility that smaller flight impact simulators could not match.

The flight impact team was also able to conduct in-house research projects and publish the results thereof. In the early 1980s, for example, it accidentally discovered that, as (certain types of?) polycarbonate panels used in aircraft windshields aged, their resistance to impact decreased significantly – a discovery which came as an unpleasant surprise to the aerospace industry.

In July 1985, the crew of the 10-inch gun was reassigned to help deal with unanticipated workforce adjustments within the Structures and Materials Laboratory. As a result, testing was severely curtailed. All new foreign requests had to be declined, for example. All in all, the years 1986 to 1993 saw only 7 test programs. Some of these involved aircraft developed by Canada’s major aerospace companies, namely the Dash 8, Challenger and CRJ.

Between 1993 and 2007, the 10-inch gun was operated by a private contractor, Bosik Technologies Limited of Ottawa, on behalf of its actual owner, the Institute for Aerospace Research, or NRC Aerospace, as the NAE had been renamed in 1990. That flight impact simulator was last activated in May 2009, after almost 41 years of service. It was soon taken apart and moved to another building, on the other side of the road, for long-term storage.

And yes, that sentence was a subtle homage toward the world famous joke about a chicken and a road. You are welcome.

The Canada Aviation and Space Museum officially acquired it in December 2012.

Two copies of the 10-inch gun were commissioned in the late 1980s and early 1990s, in the United States, but you already knew that, did you not, my reading friend, having read the first part of this article. The existence of 2 copies of a flight impact simulator, used in a foreign country by separate operators, is unique in the world of bird impact testing. It testifies to the high quality of the design of Canada’s 10-inch gun.

While Canada is not the country in which flight impact simulators were originally developed, the fact is that NRC has been using such devices for almost 60 years. Few organisations on this Earth have been involved in bird strike testing longer than NRC.

The first operational flight impact simulators developed in Canada, that is the 3.75- / 3.5-inch gun and, even more so, the 10-inch gun, proved extremely useful over the years. Indeed, NRC played a crucial role in making flying safer.

At the risk of sounding a tad irreverent, yours truly would be remiss if I did not point out that it is very likely, if not almost certain, that the flight impact simulators located in Ottawa were the inspiration for the Chicken Cannon frequently put to use on the weekly comedy / satirical television show Royal Canadian Air Farce (1993-2008) of the state broadcaster Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). Would you believe that this unlikely weapon starred in its own newsroom skit, Chicken Cannon News?

The Chicken Cannon made its appearance in March 1994. It was apparently last fired in December 2008, during the show’s very popular New Year’s special, which sadly happened to be the last episode of that equally popular show.

Throughout the years, the Chicken Cannon was the responsibility of one of the show’s most popular characters, Colonel “Teresa” Stacey, played by Don Ferguson. As well as a sizeable number of rubber chickens, unless the team always used and reused the same volatile, the Chicken Cannon fired a bewildering variety of items, often food items, at photographs of individuals, either Canadian or foreign, who were deemed to be the most annoying / egregious / etc. at the time.

Members of the studio audience and viewers at home chose the targets as well as the ammunition fired. The cast of the show picked a “winner” (loser?) from the various entries. The lucky individual who had submitted said entry then fired the Chicken Cannon as the studio audience roared in approval.

Canadian politicians, including a quartet of prime ministers, proved highly popular as targets. Mind you, American politicians proved quite popular as well.

It should be noted that some targets were a tad puzzling. Why canonise Harry Potter and the pokémon Pikachu, for example?

And yes, the CBC itself was canonised during the last episode of Royal Canadian Air Farce, broadcasted in December 2008.

A brief digression if I may. Did you know that the aforementioned Ferguson was one of the brains behind the (satirical?) space opera radio serial Johnny Chase: Secret Agent of Space, broadcasted by CBC between 1978 and 1981? The eponymous science fiction hero was doing his very best to protect the Earth Empire which existed (will exist?) in 2680. Spoiler alert: the evil Torks managed to destroy the Sun, thus destroying the Earth, in season 2 (1981), a most unfortunate turn of event which seemingly forced Chase to become the de facto leader of “a rag-tag fugitive fleet on a lonely quest” – and yes, said fleet of starships was packed with “ugly bags of mostly water,” in other words humans, looking for a new home.

A brief thought. Given the frequent (innate?) tendency of Homo sapiens toward total evilness, one has to wonder what the humans of Johnny Chase: Secret Agent of Space had done to p*ss *ff the “evil” Torks before the latter felt they had no choice but to wipe out humanity. Between you and me, and the snoops of Ottawa’s Communications Security Establishment, the expression Earth Empire might be a good (bad? really bad??) indicator in that regard. You have seen the 2009 epic American science fiction motion picture Avatar, have you not? I really liked that motion picture. The good guys won. For once.

And yes, I know, the Na’vi are not really an authentic indigenous people. Dare one say that this population is a coloniser’s version of an indigenous people, with a great many stereotypes, with as the icing on the cake the cliché of clichés: the white saviour?

And yes, you are quite correct, my telephile reading friend, the first quote you just read was not from Johnny Chase: Secret Agent of Space, it was from the American science fiction television series Battlestar Galactica which was broadcasted in 1978-79.

And no, Chase and his fellow humans had not found a home when season 2 of the radio serial ended. They were off to the realm of Vung and might still be there for all I know.

By the way, in my opinion, the Anglo-Canadian-American science fiction television series Battlestar Galactica aired between October 2004 and March 2009 was / is far superior to the original series. The American actor Katee Sackhoff truly kicked *ss as the pilot Kara “Starbuck” Thrace. Frak!

Johnny Chase: Secret Agent of Space was seemingly quite popular with (male?) teenagers, and… Wow, you are quite correct again, my telephile reading friend, the second quote you just read was not from Johnny Chase: Secret Agent of Space either. It was from the American science fiction television series Star Trek: The Next Generation, season 1, episode 18, initially broadcasted in February 1988. End of digression.

A deeply controversial thought if I may. If the Chicken Cannon is still with us, hidden in a CBC warehouse, I hereby and heretofore suggest that the Canada Aviation and Space Museum would do well to consider acquiring it, the acquisition moratorium / new rules of acquisitions be damned. (Hello, EG! Profuse apologies, Quark.) That device would be a wonderful complement to the flight impact simulators present in its collection. Would it not be great to operate it on Canada Day, using photographs of individuals, either Canadian or foreign, deemed to be very most annoying / egregious / etc. at the time? Just sayin’.

And yes again, my reading friend, more aircraft of the stupendous Canada Aviation and Space Museum have been mentioned in this article than in any other put on line since July 2017. Oh, happy day!

This writer wishes to thank all the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, not theirs.

Yours truly knows how fleeting resolutions for the new year can be (tend to be?) but I hereby and heretofore endeavour to valiantly attempt to be briefer in my perorations.

See you next year.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)