Frankly, my dear, we did give a dam: Canada and the Warsak dam in Pakistan

As salamu alaykum, my reading friend. We are gathered here today to look into one of the many examples of the contributions made by Canada over the years to the development of developing countries. And yes, the example yours truly has in mind is the Warsak dam, in Pakistan – a major technological contribution if I may say (type?) so.

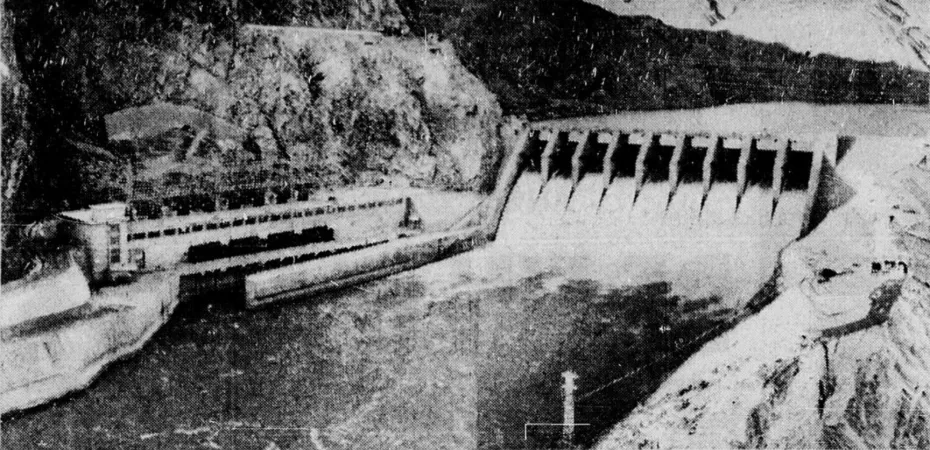

Let us begin by going over the caption of the photograph you just saw, which was published in the 27 January 1961 edition of the only French language daily newspaper of Ottawa, Ontario, Le Droit.

$ 60,000,000 Dam - Pakistan’s industry and agriculture will experience a new boom following the inauguration of the Great Warsak Dam, built on the Kabu [sic] River, [1,600 kilometers] 1,000 miles north of Karachi. On the right, we see the flow of water through the huge gates [12 meters] 40 feet high by [12 meters] 40 feet wide. The dam will always remain a monument of Canada-Pakistan cooperation in the Colombo Plan.

To paraphrase the lead singer of the American new wave band Talking Heads, in its 1981 hit Once in a lifetime, you may ask yourself what the Colombo Plan was / is. A good question.

The Colombo Plan for Co-operative Economic Development in South and South-East Asia, or Colombo Plan for short, was hatched during the Commonwealth Conference on Foreign Affairs held in Colombo, Ceylon (today’s Sri Lanka), in January 1950. Its overt goal was to assist the economic development of South and South-East Asia, read Ceylon, India and Pakistan, using certain sums of money donated by Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

And yes, the Cold War being the Cold War, the Colombo Plan was also intended to help the governments of these newly independent countries to battle the communist movements and parties within their borders.

Mind you, there were seemingly people within the British government who were concerned that the governments of Ceylon, India and Pakistan, which were in dire need of money to develop their economy, might call the loans their pre-independence, British-controlled governments had made to the United Kingdom during the Second World War. Such legitimate demands for their money back would have further aggravated the dire financial situation the United Kingdom was facing at the time. The Colombo Plan might thus be seen, in part, as a way to, if yours truly may be brutal, shovel part of the fully justified financial needs of Ceylon, India and Pakistan in the backyards of Australia, Canada and New Zealand. One has to wonder if these countries were fully aware of what might have been going on.

And no, the South African government, being the nice white outfit that it was, showed no interest in taking part, and this even though it had a representative at the conference. In fairness, one might argue that the governments and populations of Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom contained their fair share of racist Home sapiens.

Incidentally, the Cold War still being the Cold War, the Colombo Plan soon attracted new members. By late 1958, 2 other countries, non-Commonwealth countries to boot, were contributing moolah to the collective pot, namely the United States and Japan. One has to wonder if the latter joined the group of its own volition.

The list of recipient countries, on the other hand, had gone from the trio mentioned above to 12 independent countries (Burma (today’s Myanmar), Cambodia, Ceylon, India, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, South Vietnam and Thailand), as well as 4 territories controlled more or less directly by the United Kingdom (Borneo, Brunei, Sarawak and Singapore).

And yes, the Colombo Plan, known since 1977 as the Colombo Plan for Cooperative Economic and Social Development in Asia and the Pacific, was / is still going strong in early 2021. Indeed, there were / are 27 member countries in the organisation. Canada was / is no longer one of them, however. The government led by Martin Bryan Mulroney pulled out in 1992. The United Kingdom had done so the previous year, but back to our story.

The story of the Warsak dam began around 1947 when the Public Works Department of the government of what was then the North West Frontier Province of India began to look into the possibility of building a dam on the Kabul River, not too far from Peshawar, a bustling city and the capital of the province.

This region of India was / is semidesertic and mountainous, with many narrow gorges. With only a few small parcels of land they could grow food on, and small herds of goats to provide meat, the local Pashtun tribes often had to resort to predatory tactics against slightly better off people living in more fertile locations. They also had to resort to smuggling, to and from Afghanistan or China. The products they transported were quite varied, and not always legal.

In any event, the British military forces stationed in the North West Frontier Province tried for decades to bring under control the strongly independent people living there, with varying success. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Royal Air Force (RAF) had a go at it, with limited success, and… Here I am, digressing again. Sorry.

Still, yours truly would like to point out that the Hawker Hind light bomber of the utterly amazing Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, is very similar to the Hawker Harts and Audaxes flown by RAF crews in the North West Frontier Province during the 1930s. Would you believe that the museum’s aircraft was operated by the Šāaêy Dāfǧānstān Aoāyy Dzoāk, or royal Afghan air force, between the late 1930s and some point in the 1940s?

Now, you may ask yourself why the government of Pakistan wanted to build a dam in the North West Frontier Province. A good question. Faced with a rapidly growing population, and limited amounts of cultivable land, it needed water to irrigate additional tracts of land which could be used to feed the growing number of people. Mind you, the government also needed more and more electricity to power the new industries it wanted to create to improve the standard of living of said people.

In any event, a consulting and designing conglomerate formed by 3 well known and respected foreign consulting firms was asked to submit an interim project report on the Warsak dam, which was seemingly named after a mud hut village located nearby.

Whether or not the contract was awarded before or after India and Pakistan became independent countries, in August 1947, is unclear. In any event, again, the site of the future dam found itself in West Pakistan, the western half of Pakistan – a country split in two as a result of the partition of India.

Oh, by the way, the firms which formed said conglomerate, Merz Rendel Vatten (Pakistan), were

- Merz & McClellan Consulting Engineers Limited, a British electrical and mechanical engineering consultant,

- Rendel, Palmer and Tritton Limited, a British civil engineering consultant, and

- Aktiebolaget Vattenbyggnadsbyran, a Swedish hydroelectric engineering consultant.

If one is to believe a respected Australian columnist, Douglas Wilkie, in a column published in February 1951, some Pashtun tribes were delaying the project in some fashion or other.

In any event, Merz Rendel Vatten (Pakistan) submitted its interim project report in 1951. The Pakistani government thoroughly examined it, as well as one dealing with a dam project on the Indus River. It chose to proceed with the Warsak dam project. Work on the site began soon after.

As this was taking place, the federal government, all right, all right, the Canadian government, took an interest in the Pakistani project. Canada and Pakistan seemingly signed some sort of agreement in 1952. Thus was born the largest humanitarian project funded thus far by Canada.

An individual who played a significant role in Canada’s involvement was the administrator of the International Economic and Technical Division of Canada’s Department of External Affairs, which oversaw to the Colombo Plan, between 1951 and 1957. British-born Reginald George “Nik” Cavell was quite the character, with multiple careers before 1951 (theatre violinist, straight man to a comedian, officer in the Indian Army, horse trader, magistrate, plague prevention officer, sheep farmer, journalist, telephone company executive, secret agent, and company president (twice), and chairperson of institutes (foreign and international affairs), in countries as far apart as the United Kingdom, India, South Africa, China, Japan and Canada.

If I may be permitted to express an opinion, a rare happening as we both know, Cavell deserves if not a full doctoral dissertation, at least a master’s thesis.

Incidentally, the Department of External Affairs was not the only federal government entity connected to the Colombo Plan. Until 1960, Canada’s foreign assistance was jointly supervised by the former as well as the Department of Finance and the Department of Trade and Commerce, in the latter case through its Economic and Technical Assistance Branch. The arrangement worked reasonably well most of the time, but not very well all the time.

Canada’s Prime Minister, Louis Stephen St-Laurent, a gentleman mentioned in July 2019 and October 2020 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, visited the future site of the Warsak dam in February 1954, as part of an official visit to Pakistan.

Canada and Pakistan signed another agreement in November of that year, in Pakistan. The federal government agreed to provide more moolah, as well as equipment and technical services.

Soon after, the federal government chose H.G. Acres & Company Limited as its consultant firm. Well known for its expertise in hydroelectric engineering, the Niagara Falls, Ontario, firm was to prepare a detailed plan for the site.

The contract for the construction of the actual dam was awarded in August 1955, to a well-known Canadian construction firm. Angus Robertson (Overseas) Limited did the work on behalf of Angus Robertson Limited of Toronto, Ontario.

Incidentally, the first shipment of Canadian equipment / machinery left Montréal that very month, aboard the SS City of Doncaster, a cargo ship owned by a British shipping firm.

Canada’s Secretary of State for External Affairs visited the site in November 1955, with his spouse, Maryon Elspeth Moody Pearson, as part of an official visit to Pakistan. Would you believe that Lester Bowles “Mike” Pearson allegedly pressed the button which detonated the first explosive charge set at Warsak?

Better yet, perhaps, Pashtun tribal leaders presented gifts to Pearson, namely a few rifles, a couple of daggers and a handmade revolver, as gestures of thanks for the work done at Warsak. Although initially taken aback, the Canadian quickly tied a dagger sash around his waist, as his spouse immortalised the scene with a photograph – or maybe two.

By the end of 1955, 200 or so Canadians, many if not most of them engineers and technicians, were at Warsak. This number had grown to about 300 in 1957. Many of said engineers and technicians had come to this remote location with their spouse and children. They lived in air conditioned bungalows in a village built from scratch by the Pakistani government.

Well before the construction of the dam was completed, said village, dare I say (type?) gated community, sometimes / often known as “Little Canada,” had paved streets, a lighted tennis court, a school, a pool, a library, a 50-bed hospital, a dance hall, a commissary, a church, and a bowling alley. And let’s not forget the indispensable administrative buildings. The aforementioned recreational activities were seemingly located within or around a recreational centre of sort.

All in all, life was good, if one did not think too much about the snakes and scorpions. Numerous Canadian families vacationed in Afghanistan, India and / or Pakistan during their stay at Warsak.

The Pakistani armed guards which patrolled and protected the site of the dam seemingly kept a close eye on the Canadian village.

Numerous Pakistani workers and engineers looked with undisguised envy at the luxurious accommodations of the Canadian expatriates. But wait, there was more.

During the summer of 1959, the son of the chief of the Pakistani military mission in Washington, District of Columbia, Major General Mian Hayaud Din, stated that all was not well at “Little Canada.” Indeed, Mian Ahmed Hayaud Din stated that a number of male Canadians had not been happy to see their spouses dancing with Pakistani engineers during an event organised therein. Mind you, a number of spouses of said engineers were not too thrilled either. The presence of the Canadians was becoming a source of trouble, said Hayaud Din.

And no, the event in question was not the only time that Canadian and Pakistanis fraternised

Yours truly wonders if “Little Canada” still stood as of 2021, and who might be using it, but I digress.

Rumours circulating during the summer of 1959 that the village was to be turned over to the Pākistān Fizā’iyah once the dam was completed. Said rumours stated that the Pakistani air force would actually move its headquarters from Karachi to Warsak. These rumours proved unfounded.

Yours truly cannot say who moved into the “Little Canada” after the departure of the Canadians. Housing the engineers and technicians who controlled and maintained the site seemed a logical choice, but what do I know?

Sadly, this idyllic location may, I repeat may, have been used as a temporary detention centre in the spring of 1973. That story had begun in early 1971. Increasingly frustrated by the treatment it received from the Pakistani government, much of the population of East Pakistan rebelled. They wanted their own country. The independence of Bangladesh was thus proclaimed in March. Government repression was severe. Up to 10 million people (15 % of the population!) fled into India, whose government gave them refuge and offered assistance to the independence movement. Infuriated by this assistance, the Pakistani government launched attacks against India in December. The Indo-Pakistani war of 1971 lasted but 13 days. The Pakistani armed forces were soundly defeated and had to vacate East Pakistan / Bangladesh.

It looks as if an exchange of prisoners (6 000 or so Pakistani soldiers and 10 000 or so Bengali / Bangladeshi civilians) was arranged in the spring of 1973, and that’s when “Little Canada” entered the picture. About 200 Bengalis stranded in Pakistan were moved out of their government housing in early May as part of a massive police operation. They were detained in 3 locations, including Warsak, before their repatriation to Bangladesh.

And back to the Warsak dam project we go. It was decided at some point to install 4 electrical generators, made by Canadian General Electric Company Limited of Toronto, a subsidiary of American industrial giant General Electric Company (GE) – which was not the number initially proposed. This being said (typed?), provision was made to include another pair of generators of similar power at a later date.

Said generators were donated to Pakistan by the federal government, which also donated the gigantic control valves, made by Canadian Vickers Limited of Montréal, Québec, as well as a construction workshop.

Would you like to know that GE was mentioned in June 2018 and January 2020 issues of our… There was no need to get upset. I was merely asking.

And just for that, I will have the infinite pleasure of pointing out that the turbines of the dam were made by Dominion Engineering Company Limited of Montréal – a firm mentioned in a May 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. Topping that off, Canadian Vickers was mentioned several / many times in that publication, and this since May 2018, but back to our dam.

The closeness of the border with Afghanistan meant that caution had to be exercised in designing said dam to prevent the occurrence of transborder flooding.

Speaking (typing?) of water, the overall plan for the region provided for irrigation facilities for up to 570 square kilometres (220 square miles) of land on both sides of the Kabul River – which was nothing to sneeze at. Whether or not that figure was achieved is unclear, a figure of 480 or so square kilometres (185 square miles) being mentioned in the late 1950s. In any event, the irrigated area was expected to produce huge amounts of food each year for the 4 million people of the region.

It should also be acknowledged that the construction of the dam helped to bring some sort of stability to the northern regions of West Pakistan, a volatile area if there was / is one, where Afghanistan, China. India, Pakistan and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics met more or less directly, and this for several years, by providing employment, back breaking employment mind you, for Pashtun men from tribes like the Mulagori, Mohmand and Afridi.

At the height of the project, 10 000 or so men toiled on the site, on two shifts. By May 1959, only 7 000 or so were left. This number quickly decreased over the following weeks and months.

The men were seemingly paid 32 or so cents a day, which amounts to about $ 2.85 a day in 2021. While this miserly sum seemed to be a mere pittance, by late 1950s local standards, it was higher than the average daily salary in Pakistan. Incidentally, the tribal leaders whose men worked on the site received a smaller sum of money per man per day.

To the surprise of the Canadians on site and, perhaps, of many Pakistanis, the Pashtun workers, which had no previous work experience on a large construction site, proved to be very good workers – a rather condescending opinion. The work experience gained by these thousands of men may well have proven useful in later years, on other sites, or so it was hoped.

It is worth noting that the Canadian director of the dam project arrived on site in 1956.

Canada and Pakistan signed yet another agreement in January 1957. This one concerned the construction of the dam’s power station. Said agreement was signed in Pakistan. The Canadian who signed the document was the country’s minister of National Health and Welfare. Joseph James Guillaume Paul Martin was on an official visit of Pakistan at the time.

As construction of the Warsak dam progressed, it was mentioned more and more in Canadian newspapers – and elsewhere. In 1957, a famous British historian who specialised in international affairs, Arnold Joseph Toynbee, visited the site and published a laudatory article for the famous American magazine Foreign Affairs. Once translated in French, said article was published (in its entirety?) in several Québec newspapers. The original version may of course have been published in other Canadian provinces.

Canada’s minister of Finance, Donald Methuen Fleming, visited the site in October 1958, during an official visit to Pakistan.

A second Prime Minister of Canada, John George Diefenbaker, a gentleman mentioned in October and November 2020 issues of our you know what, visited the site in November 1958, as part of an official journey around the globe. He was most impressed by the aforementioned village which housed 145 to 150 Canadian families – and a number of single men, for a grand total of 400 to 450 people. Indeed, Diefenbaker received a warm welcome.

At the time, the Canadians at Warsak worked under the supervision of E. Lester “Les” Miller of H.G. Acres & Company and, possibly, Corey Robbin. Given that this latter gentleman was said to have come from Fort William, Ontario, a city now integrated within Thunder Bay, yours truly wonders if an important firm located there, a firm mentioned in May 2019 and July 2020 issues of our yadda yadda, Canadian Car and Foundry Company Limited, played a role in the Warsak dam project.

Did you know that Prince Philip of house Mountbatten, born Philippos of Greece and Denmark of house Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, visited the site, as well as well as “Little Canada,” in February 1959?

In late June, during an address made to a group of engineers and scientists, during a luncheon in Toronto, during a June and July visit of Canada with his regal spouse, the prince praised Canada and Canadians for their contribution to the Colombo Plan, not to mention their role in the construction of the Warsak dam. The British royal couple was on some sort of world tour at the time.

A team of Canadian engineers went to Pakistan in November 1959. Led by a top power station superintendent, Kenneth S. Gemmel (or Gemmell?) of the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario, today’s Ontario Power Generation Incorporated and Hydro One Limited, said team was to train the team of Pakistani engineers and technicians which would run the power station of the Warsak dam. It may have spent a year in Pakistan.

An additional engineer joined the team in March 1960. R.G. Radley worked for Canadian Westinghouse Company Limited of Hamilton, Ontario, a subsidiary of the American giant Westinghouse Electric Corporation. A.E. Lock, an experienced operator at the Cornwall, Ontario, power station of the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario, made the trip with him.

And yes, the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario was mentioned in a December 2020 issue of our you know hat.

In January 1960, a Lieutenant General Azam, quite possibly Lieutenant General Muhammad Azam Khan, Pakistan’s minister of refugee rehabilitation, inaugurated the site’s 5.5 kilometre (3.5 mile) long irrigation tunnel dug through solid rock, starting at both ends, over a period of 30 or so months. Azam Khan thanked the federal government for its generous contribution to the project. Canada’s High Commissioner in Pakistan, Herbert Owen “Herb” Moran, graciously accepted these thanks and congratulated the Pakistani government.

The Warsak dam was officially deemed complete in mid July 1960. It officially began to produce electricity on 14 August 1960 – 14 August being Pakistan’s independence day. As the giant generators gradually reached their full power, the electrical production capacity of West Pakistan more than doubled.

It is with sadness that I have to point out that a 25-year old Canadian engineer died in an accident in May 1960. Jerry Sexton had arrived in Pakistan in 1958. He was apparently the only Canadian to die during construction of the Warsak dam. More than a few Pakistanis presumably lost their lives on the site.

The Warsak dam was officially inaugurated on 22 January 1961 by the president of Pakistan, Field Marshall Muhammad Ayub Khan, in the presence of numerous Canadians, including Gordon Minto Churchill, minister of Veterans Affairs and leader of the government in the House of Commons, and the aforementioned Moran, then head of the newly created External Aid Office of the Department of External Affairs.

Would you believe that the person who promoted Ayub Khan to the ultimate rank of Field Marshall was… Ayub Khan? I kid you not. He had done so in 1959. It must be nice to have the power to give oneself a promotion, or a pay raise, without having to answer to anyone.

If the presence of a Veterans Affairs minister at the inauguration of a dam in Pakistan seems odd to you, my reading friend, please allow me to point out that Churchill, who was not related to the other Churchill, Sir Winston Leonard Spencer “Winnie” Churchill, an individual mentioned several times in our you know what since May 2019, was minister of Trade and Commerce between June 1957 and October 1960.

Warsak was actually one of the 5 stops made by Churchill and Moran in India and Pakistan. The dynamic duo attended 4 other inauguration ceremonies in quick succession.

Queen Elizabeth II, born Elizabeth Alexandra Mary of house Windsor, visited the Warsak dam in February 1961. She was escorted by the governor of West Pakistan, Malik Amir Muhammad Khan. Whether or not Canadians were present to wish her well is unclear.

The stamp issued by the Pakistani government to celebrate the completion of the Warsak dam.

At some point in 1961, the Pakistani post office department issued a stamp to commemorate the completion of the Warsak dam. Said stamp may, I repeat may, have been issued on 1 July 1961, a date presumably chosen by the Pakistani government to please its Canadian counterpart. As we both know, 1 July was / is Canada’s national holiday. In any event, the first covers for that stamp carry that date.

The likelihood that the Pakistani stamp was issued on 1 July is bolstered by the fact that the Post Office Department of Canada seemingly issued a 5 cent stamp which celebrated the Colombo Plan on… 1 July 1961. Said stamp may, I repeat may, have shown the Warsak dam.

Better yet, it looks as if the National Film Board, a world famous federal institution mentioned several times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since July 2018, launched a documentary entitled Ten Years from Colombo on 1 July 1961. Indeed, said documentary film may have been shown on Canadian television in early July, or in late June.

Filmed in cooperation with the governments of Ceylon, India and Pakistan, Ten Years from Colombo highlighted Canada’s contributions to the Colombo Plan, including, of course, the Warsak dam. In that regard, the aforementioned Angus Robertson graciously helped the film crew, directed by well known, talented and respected director Donald Fraser, as best it could.

The French language adaptation of the film was made by famous Québec / Canadian director / painter / producer / screenwriter Gilles Carle, a gentleman who directed some of the best and most popular / famous Québec / Canadian motion pictures of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, from The Merry World of Léopold Z (1965) to Maria Chapdelaine (1983).

The narrator of said French language adaptation, entitled Plan de Colombo – Dix ans après, was a well-known radio and television announcer with the Canadian state radio television broadcaster, the Société Radio-Canada.

Incidentally, Raymond Charette was one of the 5 gentlemen who hosted the very popular popular science television series Atome et galaxies, broadcasted by the Société Radio-Canada between October 1963 and January 1971. On the job between October 1966 and October 1969, Barrette was at the helm of this classic series, aimed at young people aged 12 to 17, longer than any other of his colleagues.

For the life of me, yours truly cannot remember whether or not I was an assiduous viewer of Atome et galaxies, but I digress. For the last time. This week. Back to our dam we go.

Sadly, by late 1965, the reservoir of the Warsak dam was silted up all the way to the crest of the spillways. As a result, the water rushing into the power station was loaded with sediment, which caused wear and tear on the moving parts of the turbines.

A thought if may. How is it that the various consultants, highly paid no doubt, which worked on the project at various times did not twig on the possibility that sediment could become an issue? Food for thought.

Incidentally, Canada paid for the installation of the pair of electrical generators for which provision had been made in the original design. They too were made by Canadian General Electric. As well, the turbines were made by the firm which had made those installed in 1960, the aforementioned Dominion Engineering. This time around, however, the transformers were made in the United States rather than Canada. This second phase in the history of the dam was completed in 1981.

At some point in the 1980s, yours truly think, a well-known hydroelectric engineering consultant firm from Montréal, Rousseau, Sauvé, Warren Incorporée, cooperated with Qaumi Khidmaat Tameeri Pakistan, or National Engineering Services Pakistan, to look into the silting up of the reservoir of the dam, a preoccupying matter if there was one. The cost of any serious alleviating work precluded the suggestions they made from being implemented.

Would you believe that Rousseau, Sauvé, Warren was founded by engineers who had worked for the Montréal office of H.G. Acres & Company? Ours is a small and interconnected world.

Between 1957 and 1979, the federal government may, I repeat may, have contributed 300 million dollars to Pakistan’s electrical power sector. One has to wonder how much dough was added to that impressive pile between 1979 and 2021.

Well, you probably have places to do and things to go, or vice versa. Ta ta for now.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)