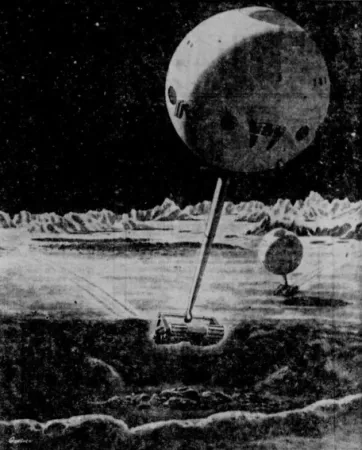

I’m just not sure this vehicle was well thought through: The Moon car of astronautic pioneer Hermann Julius Oberth

Guten tag, my reading friend. Are you having fun today? Wunberbar. Given this state of jocularity, I will presume to impose upon you for a few minutes. I can only presume that the illustration above caught your attention. As you must painfully know by now, yours truly cannot resist an opportunity to pontificate. After all, either one is a curator or one is not.

Anyway, said illustration accompanied one of many articles on the mysteries of the universe published between May 1960 and February 1963, on a more or less weekly basis, by L’Action catholique / L’Action – a Québec, Québec daily newspaper we have come across several times in our blog / bulletin / thingee. Mind you, La Tribune, a Sherbrooke, Québec, daily newspaper also published many articles on the mysteries of the universe from that same series between August 1958 and April 1962, again on a more or less weekly basis. The very important daily newspaper La Presse, from Montréal, Québec, seemingly published only a few articles on the mysteries of the universe from that same series, between June and August 1966.

The author of all these quite fascinating articles was Israel Monroe Levitt, then director of the Fels Planetarium of the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which were both mentioned in a November 2019 issue of our you know what. Levitt was a fascinating individual who worked at the Franklin Institute from the mid 1930s to the early 1970s. He soared to the heavens in January 2004, at the ripe old age of 96.

Levitt began to write his articles, in English of course, for American newspapers, in 1952. This work eventually turned into an internationally syndicated column, entitled Wonders of the Universe, which ran for almost 19 years – which means yours truly has a long loooong way to go before I can top that. Would you believe that Wonders of the Universe was eventually published in 22 countries, not necessarily at the same time of course, and in 19 languages? To quote the evil Asgardian Loki Laufeysson in the 2013 movie Thor: The Dark World, I’m impressed.

Equally impressive is the fact that Levitt seemingly originated, in 1960 I believe, the idea of putting the American space program on wheels, so to speak, so that high school and college students all across the United States could see what it was all about. The management of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), a world famous organisation mentioned many times since July 2018 in our you know what, loved the idea. Thus was born the Spacemobile Program.

The first Spacemobile hit the road in 1961. It consisted of a vehicle chock full of educational material, especially models (satellites, rockets, capsules, etc.). As time went by, the content of the Spacemobiles changed, of course. Movies may have been included from day one, and a very cool liquid nitrogen demonstration thrilled the countless students who saw it. The length of each Spacemobile show / presentation varied, of course, but 50 or so minutes may have been a good average. Throughout its history, the Spacemobile Program was operated by a contractor. The Franklin Institute ran it in its early days, for example.

Would you believe that 44 Spacemobile vehicles were still on the road in 1980? Eight of them were travelling outside the United States, thanks to the United States Department of State, which recognised a good propaganda exercise when it saw one. And if that seems a tad cynical, well, not everyone liked the United States in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. A cool presentation made in one’s native language, by a charismatic individual trained by NASA, but paid by the local government or some other local entity, could help to improve that country’s image. As time went by, NASA came to realise that average people liked the presentations as much as students did, which brought in a whole new audience. Over the years, Spacemobiles visited more than 60 countries on every continent, except Antarctica – and a visit down there would have been a welcome change from the boredom of an Antarctic winter. Just sayin’.

Incidentally, the Spacemobile Program became the Space Science Education Project, which became the Aerospace Education Services Project, which no longer existed as of 2020, pity, but back to our topic of the week.

Our story began in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in a region of the Lands of the crown of Saint Stephen, or Transleithania, known as Transylvania, an Eastern European territory located within today’s Romania which happened to be the home and native land of Vlad III, a 15th century ruler of Wallachia, another Eastern European territory located within today’s Romania. And yes, Vlad III was / is better known as Vlad Ţepeş or Vlad Drăculea, the very individual whose violent life inspired Abraham “Bram” Stoker when the latter wrote one of the most famous horror novels of all times, Dracula, published in 1897. I will grant you that, my reading friend, you know your horror.

Anyway, back to Transylvania. A boy was born there, in June 1894. He was baptised Hermann Julius Oberth. During the second half of the 1900s, this surgeon’s son discovered the futuristic novel of Jules Gabriel Verne, a gentleman mentioned several times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since June 2018. He was especially fond of Von der Erde zum Mond and Reisen um den Mond, which detailed the journey to the Moon of a few male Homo sapiens aboard a hollowed out shell fired by a ginormous cannon buried in the fair state of Florida. Yes, yes, in Florida, not too far from the location of the most famous spaceport in the world, the one operated by an organisation mentioned many times in our you know what.

Bright lad that he was, Oberth soon concluded that using a cannon to send humans into space made no sense whatsoever. The shock felt by the passengers of a hollowed out shell would be more than lethal. Oberth concluded that a rocket was the way to go. He may even have put together a small rocket before the end of the 1900s.

A medical student in Munich, German Empire, in 1914, when the First World War began, Oberth was one of the millions of young men around the globe who had to drop everything and put on a uniform. After some time spent at the front, in the infantry, fighting soldiers of the Russian Empire he had no quarrel with, if I may paraphrase the Greatest, Mohammed Ali, born Cassius Marcellus Clay, Junior, he ended up in a medical unit. It was not a pleasant experience.

After the end of the conflict, which led to the breakup of the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires, and the (re)birth of numerous countries in Europe, Oberth concluded that medicine was not for him. He began to study physics in 1919, and moved to Germany.

Oberth’s doctoral dissertation, on rocketry and space travel, completed in 1922, was rejected, because its topic was simply too far out and / or because no one knew enough about this topic to see whether or not the ideas contained therein made any sense. In any event, Oberth went to a German publisher and paid to have his dissertation published, in 1923. Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen was certainly not a bestseller but this book on rockets in interplanetary space eventually caught the eye of German rocket enthusiasts.

Over the following years, Oberth worked on his text, after completing his daily work as a secondary school physics and mathematics professor in Romania, and this even though he was technically an Austrian citizen. By 1929, his 90 or so page dissertation had ballooned to more than 400 pages – something I can certainly sympathise with and understand. That year, Oberth published Wege zur Raumschiffahrt, a founding work on how to achieve spaceflight that also caught the eye of German rocket enthusiasts who, by then, were members of the Verein für Raumschiffahrt (VfR), one of the most important group of rocket enthusiasts in Germany and the first one in the world known to have built a rocket. Founded in July 1927, this society for spaceflight was mentioned in February and September 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

In 1928 or 1929, Oberth began to work as one of the scientific / technical advisers on a film project put forward by a famous director, Friedrich Christian Anton “Fritz” Lang, who, like him, had been born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The silent motion picture in question, Frau im Mond, in English By Rocket to the Moon / Woman in the Moon, shown for the first time in October 1929, was among the first serious science fiction films ever made.

Another one would of course be Himmelskibet, in English A trip to Mars, a superb Danish film shown for the first time in February 1918 and mentioned in a February 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

And yes, yours truly realises that Frau im Mond’s premise that a breathable atmosphere was present on the hidden face of the Moon made no sense. The idea, proposed around 1856 by Danish German mathematical astronomer Peter Andreas Jansen, had been all but smashed in the early 1870s.

Would you believe that Friede, the lunar rocket portrayed in Frau im Mond, was the first realistic rocket ever shown on film – and it was seen by a large number of people around the globe. It was, of course, based on the Model E rocket mentioned in Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen and, in greater detail, in Wege zur Raumschiffahrt.

And yes, the famous countdown heard every time a rocket is sent into space was seen for the first time in Frau im Mond. Seen, yes, seen, it was / is a silent film. Sigh.

Would you also believe that Oberth was supposed to build a small working rocket, presumably similar in appearance to Friede? He and Lang may even have hoped to launch it at the premiere of the film. I kid you not. Given the limited technology of the time, however, the project had to be abandoned.

In 1929 or 1930, Oberth joined the aforementioned VfR. And yes, by and large, the members of this association loved Frau im Mond, even though the presence of a breathable atmosphere on the hidden face of the Moon made no sense. One of the young members of the VfR who readily acknowledged the importance of Oberth’s work in their thinking was Wernher Magnus Maximilian von Braun, one of the key figures of the American space program and an individual whose National Socialist past was carefully buried for many years. Von Braun was mentioned several / many times in our you know what since January 2019.

Between 1941 and 1943, Oberth was involved in a quite peripheral manner in the development of the A-4 ballistic missile, a terror weapon also / better known as the V-2. Interestingly, he may have thought that the impact of this very advanced weapon on the outcome of the Second World War did not fully justify the huge sums of money spent on it – an opinion I share if I may say so. In any event, he joined in 1943 the staff of Westfälisch-Anhaltsische Sprengtoff Aktiengesellschaft, an explosive and solid rocket fuel manufacturing firm, as a consultant involved in the design of anti-aircraft rockets / missiles. Oberth was still there when the Second World War ended, in 1945.

Oberth left West Germany for Switzerland in 1948, with his family. They secretly went to Italy in 1950, under false names, so that Oberth could work for the Marina Militare, on an equally secret anti-aircraft missile project. Oberth’s contract was terminated in early 1953 as a result of the limited success enjoyed by his team. No missile was actually completed, let alone tested.

Why the secrecy, you ask, my reading friend? Well, the centrist pro-North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) coalition government of Italy did not want to attract the attention of powerful anti-NATO opposition parties, namely the Partito Socialista Italiano and the Partito Communista Italiano.

Once back in West Germany, Oberth published another book, Menschen im Weltraum: Neue Projekte für Raketen- und Raumfahrt, in 1953, in which he wrote about the future of mankind in space. An English translation of this book, Man into Space: New Projects for Rocket and Space Travel, came out in 1957. A French translation, Les hommes dans l’espace : Des satellites artificiels aux planètes habitables, came out in 1955, by the way. Vive la France!

Oberth spent some time in the United States, around 1955-58 and 1960-62. During his first stay, he worked on future civilian space project ideas at the Ordnance Guided Missile Center / Army Ballistic Missile Agency, an organisation mentioned in February and May 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, where the aforementioned von Braun was one of the bigwigs. During his second stay in the United States, Oberth worked for the Convair Division of General Dynamics Corporation, an American defence industry giant mentioned in many issues of our you know what since March 2018. He acted as a consultant on the Convair SM-65 / CGM-16 Atlas intercontinental ballistic missile fitted with a thermonuclear warhead.

It may be worth noting, or not, that Oberth was deeply interested in flying saucers during the 1950s and 1960s – if not later. Indeed, he strongly believed that these unidentified flying objects were very real and came from other worlds. In fairness, it should be noted that numerous individuals expressed similar opinions at the time.

Another example of Oberth’s originality, dare one say borderline eccentricity, was / is the Moon car, and… Finally? What do you mean, finally? It took yours truly less than 30 paragraphs to get back to our topic of the day. That’s a lot less than 6 hamburgers and scotch all night, if I may quote British rock band Dire Straits’ 1991 hit song Heavy Fuel.

The Oberth Moon car as imagined in 1954 in Menschen im Weltraum. Hermann Oberth, Les hommes dans l’espace: Des satellites artificiels aux planètes habitables, cover.

The Moon car, say I, was first proposed in Menschen im Weltraum. A more detailed description came out in 1959 in a book entitled Das Mond Auto, which was published in English, in 1959 I believe, as The Moon Car.

The 10 000 or so kilogrammes (22 000 pounds), Earth weight of course, Moon car consisted of a 5 metre (about 16.5 feet) diameter spherical compartment for the crew to which a single telescopic leg was attached, to which was attached an unpiloted yet powered caterpillar track element. The electricity needed to power this vehicle would be provided by the sun and some sort of hydrogen peroxide turbine. This electricity would power the large gyroscope needed to keep the Moon car driving along in a vertical position. Just imagine an 18 metre (60 feet) high pogo stick travelling at speeds of up to 150 kilometres/hour (close to 95 miles/hour) and you get the idea. I kid you not.

If the crew of the Moon car spotted an obstacle that could not be crossed, at low speed of course, a canyon or crevasse for example, the pilot would retract the telescopic leg inside the spherical compartment. After looking into an instrument which would give him the width of the obstacle and the distance separating it from the Moon car, he (It would have to be a he. I cannot imagine a female Homo sapiens getting anywhere near a Moon car.), he, say I, would push a button / lever / thingee, thus shoving a (controllable?) volume of compressed air inside the telescopic leg. Said leg would extend (more or less fully?), sending the Moon car in the, err, not air, not sky, I think, not space either. Err. Well, it sent the Moon car upward, up to 125 metres (400 feet) above the surface of our satellite. A casm, sorry, chasm up to 100 metre (330 feet) wide could be vanquished.

How would it actually work, you ask? And how would this ginormous behemoth, this mechanical kangaroo, this frivolous idea of a competent eccentric, be sent to the Moon? Well, Oberth being a theorist, he did not spend too much time on mean technical details.

At the risk of sounding mean, yours truly is beginning to understand why the aforementioned Marina Militare’s secret anti-aircraft missile project went nowhere, but I digress.

In the article which included the illustration at the beginning of this article, the aforementioned Levitt, you do remember him, don’t you, stated that, even though Oberth’s Moon car project was quite adequate, it was not a practical proposition in 1960. Very kind words if I may say so.

Now, I ask you, my reading friend, was the Moon car the first lunar vehicle imagined by a human? Good answer. Can you name that human? No? No problem. And yes, I looked it up and… Get back in your chair. I’m not done with you yet. Besides, it’s a cool, cool story.

The first moon vehicle I dug up, but not the very first I’m afraid, was imagined by an Austro Hungarian alpinist / author / philosopher / translator of Polish extraction, Jerzy Żuławki, in Na grebnym globie: Rękopis z księżyca, published in book form in 1903 – the first of 3 volumes in a lunar trilogy translated in most European languages but not in English, but then is England part of Europe? Sorry, that too was mean.

The title of the French translation of the book, by the way, was / is Sur le globe d’argent : Manuscrit de la Lune.

Even though Żuławki sent his astronauts to the Moon by means of a cannon, a bad idea as we all know, his lunar vehicle was a sensible machine powered by electricity. Its 4 wheels could be replaced, by hand, during a moonwalk, by legs / claws if its crew encountered rough terrain. Would you believe that a member of the expedition who decided to stay on Earth just before departure was named… Braun? Ours is indeed a small world, but back to our story.

Oberth formally retired in 1962, the year he became an honorary member of the local branch of the Bund der Vertriebenen, a not for profit organisation which represented the interest of the many ethnic Germans who had fled or were forced out of Eastern Europe after the Second World War and which had links with far / extreme right parties and groups. In 1965, he joined the newly formed Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (NPD). Oberth may have left this far / extreme right political party in 1967. Whether or not he broke all ties with the NPD is unclear, given the possibility, I repeat the possibility, that, at least once in a while, he donated money to help elderly members of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeitpartei.

A lot of people in Europe, and elsewhere, had very dark pasts they buried as deeply as they could during the years which followed the Second World War.

Oberth died in December 1989. He was 95 years old.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)