But sadly, like so many great minds, Québec television pioneer John D’Alton Woodlock was gone too soon – and quickly forgotten

Greetings, my reading friend, and welcome to another day for you and me in paradise. As you know, there are people on this Earth who leave it far too soon. The passing of such people is all the more regrettable as you and I can name a host of people the planet could very well do without. Especially now. Yours truly would like to discuss with you today of one of those people who leave our little blue marble far too early.

John D’Alton Woodlock was apparently born in 1916, in Montréal, Québec. His apparently financially well-off family paid for his education at a well-known private elementary and secondary school in Montréal, Lower Canada College. Woodlock also took (college / university level?) courses in Boston, Massachusetts.

Woodlock was the nephew of a pioneer of business education in Canada, the Quebecer Eugene John O’Sullivan, the founder of a series of eponymous private business schools in Ontario and the Atlantic provinces and, in 1916, of the O’Sullivan College of Business Administration Registered in Montréal. His mother, Josephine Woodlock, born Dumas, indeed seemingly became the proprietress of the latter institution upon O’Sullivan’s death in June 1941, but I digress.

Woodlock had been interested in what we now call electronics from the mid-1920s onward. He made a radio receiver in 1925 or 1928. Woodlock was only 9 or 12 years old at the time. He apparently had a ham radio equipment as early as around 1932. Woodlock cooperated at that time with a childhood friend, Maurice Dubreuil of Lavaltrie, Québec. He began to work in the radio industry (maintenance and repair) in the 1930s.

Let us now move to 1947. Now a technician / radio engineer, Woodlock’s occupation was the maintenance and repair of the radio equipment for the municipal police services surrounding his home, in Iberville, a municipality that is now part of Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu.

Indeed, Woodlock was one of the many Québec amateur radio operators of the time. Among his friends were well-known radio amateur operators like Franco-Quebecer violinist and composer Maurice Durieux and Québec radio announcer / producer Marcel Sylvain. Woodlock’s equipment was so effective that he contacted a Soviet amateur radio station at least once.

Woodlock’s great passion was no longer radio, however. Nay. It was television. He dreamt, talked and ate television. In English as in French. Indeed, Woodlock was bilingual. Having no one to talk to, he contacted television engineers in New York City, New York, who were also radio amateurs, in order to obtain information.

Realising that there were for all intent and purposes no television sets in furniture stores in the Montréal area, Woodlock decided to make one, for his personal pleasure, in order to receive American shows broadcasted by networks such as American Broadcasting Company, Columbia Broadcasting System Incorporated, DuMont Television Network Incorporated, and National Broadcasting Company.

Before I forget, my reading friend, please note that Woodlock gained some hands-on experience helping a friend in New York City set up his television set.

Woodlock completed, in 1947 or 1948, a television set which unfortunately did not work very well. He completed a second one, in 1949 it seemed, which worked very well indeed. Indeed, Woodlock included an amplifier in it which considerably amplified the signals received. It should be noted that the aforementioned Dubreuil seemingly became involved at one point in that television set project.

Either of these television sets might have been a device which Woodlock had purchased as an assembly kit. Yours truly wonders if the kit in question was one of the many products of the American firm Espey Manufacturing Company Incorporated, available for $ 69.50 in 1948, or just over $ 800 in 2022 currency. What do you think, my smart reading friend?

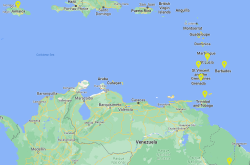

The second television set and an imposing reception antenna, a stone’s throw from his late 18th century house, allowed Woodlock to receive broadcasts from Schenectady, New York (the state, not the city), then from Boston, and even Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and, it was claimed, Miami, Florida (!). The broadcasts from Schenectady, first received in July 1949, came in loud and clear, as long as the Boston station was not transmitting. The interaction between the signals then became a problem.

These shows were in all likelihood the first to be received in Québec since the mid-1930s, since the closure of the experimental station of the Montréal radio station CKAC, then owned by the important daily La Presse.

This being said (typed?), the record company and phonograph manufacturer Victor Talking Machine Company of Canada Limited, in Montréal, broadcasted a test pattern from February 1950 onward.

People residing in Iberville and Saint-Jean, and other more distant municipalities, soon got wind of what Woodlock was up to and visited him. They came on foot, by bicycle or by automobile, causing considerable damage to his lawn. In good weather, he kindly moved his television set to the gallery of his house. When the weather was less nice, Woodlock sometimes accommodated up to 25 people in the solarium where said television set was enthroned. That scene of worship might have been complicated by the fact that the TV screen was only 12.5 x 20.5 centimetres (5 x 8 inches).

Would you believe that some somewhat cheeky visitors did not hesitate to observe, in other words snoop (in good Québecois scèner / écornifler), what Woodlock’s television set had to offer through the large window of the solarium. Pretty cheeky, was it not?

The catch was that the distance between Iberville and Schenectady was almost 280 kilometres (around 175 miles). For Boston, that distance was about 370 kilometres (about 230 miles). It was about 615 kilometres (over 380 miles) in the case of Philadelphia. That distance was close to 2 260 kilometres (nearly 1 405 miles) in the case of Miami.

In 1949, however, the effective range of a television signal usually did not exceed 80 or 95 kilometres (50 or 60 miles), as was sometimes the case in southern Ontario. While it was true that a signal from a more distant station could be received, it usually only remained visible for a few minutes. An effective range of 45 to 55 kilometres (27 to 35 miles) was more typical.

The results claimed by Woodlock therefore far exceeded, to say the least, what the average viewer would expect in 1948-49. Indeed, these results were virtually unprecedented. One wonders if Woodlock’s amplifier had something to do with that.

Woodlock contacted the television stations in Schenectady and Boston, as well as various American organisations, seemingly in New York City, to inform them of said results. Some of them were so intrigued that they sent technicians to visit him. These people could only confirm at least some of Woodlock’s claims. Some of them being radio amateurs, Woodlock informed them of his progress and issues over the following weeks and months.

Woodlock also received a visit from Aurèle Séguin, the founding director of Radio-College, a daily radio program of the Société Radio-Canada launched in 1941 aimed to supplement the information provided to high school students. You will of course remember that this state broadcaster, the French language counterpart of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, has been mentioned many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since September 2018.

Woodlock began to gain the attention of the print media in August 1949. One needs only think of the important Montréal daily The Gazette, for example, or the only French-language daily in Ottawa, Ontario, Le Droit, or the Montréal weekly Le Petit Journal. Better yet, Woodlock made headlines, small ones I will admit, in Winnipeg, Saskatoon and Edmonton, in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta.

Woodlock installed / supervised the installation of an antenna and television set in the home of one Albert Desjardins, in Montréal, in November 1949. He may, I repeat may, have manufactured the television set in question. In the evening of the same day, Woodlock, Desjardins and his spouse watched a boxing match broadcasted by the station in Schenectady via a cable which linked the latter to a station in New York City. By the way, Calogero “Charley” Fusari won over Terry Young, born Angelo DeSanza.

Would you believe that the aforementioned Dubreuil, then owner of the Hôtel Lavaltrie, in… Lavaltrie, also completed a television set no later than the spring of 1950?

He was not the only Canadian to do so. Nay. One only needs to mention Edgar Bales of Lakeview, near Toronto, Ontario. His homemade television set, completed no later than August 1948, worked just fine, except when, he claimed, aircraft interfered with the signal he got from a station in Buffalo, New York.

In September 1950, Woodlock supervised the assembly of an antenna and the installation of a television set made in the United States by Admiral Corporation in the Germain Johnson Incorporated furniture store, in Saint-Jérôme, Québec, in the Laurentians. Although located further north of the Canada-United States border than Iberville, that television set could receive broadcasts from Schenectady as well as from two cities in the state of New York, Syracuse and Rochester. Woodlock and Germain Johnson had a contract to distribute and install television sets in the Saint-Jérôme area.

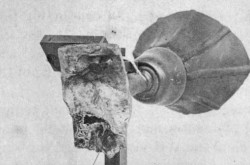

Would you also believe that, from an early September evening onward, Woodlock broadcasted his own television shows using a transmitter that he himself had designed and built? His station had as its callsign VE2HE, the callsign of his amateur radio station. These (daily?) broadcasts were picked up in various municipalities, including Lavaltrie, Montréal and Saint-Jérôme. It should be noted that they were silent, the federal legislation of the time concerning amateur radio apparently not allowing the simultaneous broadcasting of sounds and images.

Woodlock was not the only Canadian to broadcasted his own television shows. Nay. One only needs to mention Frank Marshall. This radio technician living in Winnipeg was sending images to friends over a closed circuit no later than January 1953, but I digress.

It should be noted at this point that the first two Canadian television stations, CBFT in Montréal and CBLT in Toronto, did not officially go on the air until September 1952.

Woodlock planned to begin broadcasting 16-millimetre silent films later in the fall of 1950. He also planned to broadcast wrestling and boxing matches taking place in Saint-Jean, Québec, a stone’s throw from Iberville. These projects unfortunately remained a moot point.

In late October 1950, Woodlock returned home after a trip to New York City. He went to bed and never woke up. The businessman, by then vice-president of O’Sullivan Business College Incorporated, a corporate name adopted by the aforementioned Montréal institution at an indefinite moment, was only 34 years old. His spouse, Dorothy McPhee Woodlock, in shock, was left alone with their three sone. One can only imagine what the brilliant mind of John D’Alton Woodlock might have accomplished over the following years and decades.

This writer wishes to thank all the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, not theirs.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)