“Right Port for Port;” or, How vaults in St. John’s, Newfoundland, played a crucial role in the history of a series of firms known by many names in Canada, England, Newfoundland, Portugal and the United Kingdom

Do you like port wine, my reading friend? Yours truly cannot say that I frequently imbibe glasses of that Portuguese fortified wine, but I would be lying if I did not add that I find such imbibing highly pleasurable, especially when a friend is around. (Hello, EP!)

That was / is as good a reason as any to choose vaults in Newfoundland and the firms which filled them as a topic worthy of inclusion in the pages of our incomparable blog / bulletin / thingee. Besides, 6 December is a somewhat significant day in my family. Better yet, 6 December 1958 was / is a somewhat significant anniversary day.

Not, not my anniversary. I bet you think this text is about me, don’t you, don’t you, if I may paraphrase American songwriter / singer / musician Carly Elisabeth Simon. Well, it is not. Yours truly may be that vain, but you are the one digressing this time. Yes, you are.

Let us begin this issue of our ever so incomparable blog / bulletin / thingee with a story which might very well be a figment of someone’s imagination, or a greatly embellished rendition of something that actually happened.

In any event, turn the dial on your time machine to the year 1679, my adventurous reading friend, and buckle up. Sea sickness medication might be in order.

During the summer of 1679, an otherwise unidentified trading ship owned by the Newman family of Dartmouth, England, left Oporto, Portugal, with a full load of port wine. The port wine in question might have come from warehouse owned by the Newmans.

As it sailed north toward England, that trading ship was spotted by an equally unidentified French privateer ship, which gave chase. Desperate to escape capture, and the loss of his precious cargo, the captain of the English trading ship ordered that every square centimetre (square inch) of sail be unfurled. As expected, his ship leapt before the wind. That desperate act proved to be a success. By the time the English captain felt sure his vessel had evaded its pursuer, however, he and his crew were in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean – and a serious storm was about to crash upon them.

Unwilling to risk a perilous journey toward England on an increasingly menacing ocean, the captain ordered his helmsman to change course, toward Newfoundland.

The trading ship arrived at its destination after a rather rough passage. The captain’s plans to return to England as quickly as he could, after picking up supplies, and repairing some of the damage caused by the storm, had to be put aside by worsening weather conditions, however. Indeed, the winter of 1679-80 was seemingly pretty bad in that regard.

And yes, the casks (pipes?) of port wine were rolled off the trading ship and stored ashore, possibly in caves located not too far from St. John’s, where they undoubtedly created quite a stir within the local residents.

Were the caves in question located near Pushthrough Island, where the Newman family’s trading post was located, you ask, my geographically attuned reading friend? A good question. I wish I knew.

In any event, again, the trading ship set sail for England only in the spring of 1680. It arrived shortly before the onset of summer.

As annoyed as it was by the late arrival of its vessel, the leadership of the Newman family was nonetheless happy that its precious cargo had not been lost or, worse, drunk by some dastardly Frenchmen.

To their surprise, the testers who sipped the content of at least some of the casks, to see if it was still drinkable, discovered that said content was far superior in bouquet, flavour and sweetness to the port wine delivered previously. For some unfathomable reason, the many months spent in damp Newfoundland had improved the quality of the casks’ content.

As puzzled as they were by that state of affair, the leadership of the Newman family knew a good thing when it saw it. It decreed that, from then on, every single cask of port wine the family’s trading ships would pick up in Portugal would spend many months in Newfoundland, in the cellars of its cod fishing facilities.

The end.

Yes, the end of the greatly embellished rendition of something that actually happened, if not of a figment of someone’s imagination, not the end of this article. You are not getting off that easily, you know.

And you have a question… Did port wine actually exist in 1679, you ask, my sceptical reading friend? A good question.

You see, the invention of port wine is the subject of some controversy. One school of thought, often an English one, claims that this delectable alcoholic beverage made its appearance during the 17th century, when English merchants added brandy to wine hailing from the Douro region of Portugal, in order to prevent it from souring.

Another school of thought, often a Portuguese one, claims that the idea of adding brandy to wine in order to preserve it could be dated to the so-called Age of Discovery / Age of Exploration which had begun during the 15th century, and…

Humm, those expressions bring to mind a few words, translated here, from the 98 Current Era book De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae by the Roman historian / politician Publius Cornelius Tacitus, words put in the mouth of a (real?) Caledonian war leader, Calgacos, prior to a battle in what is now Scotland: “To robbery, slaughter, plunder, they give the lying name of empire; they make a solitude and call it peace.” And yes, the robbers, slaughterers and plunderers were the Romans, but back to the so-called Age of Discovery / Age of Exploration.

You should note that what follows is shocking.

You see, something like 55 to 60 or so million people lived on the American continent in October 1492, when Christopher Columbus / Christoforo Colombo and his crews made landfall. By 1600, 6 or so million people were living on that same continent. Europeans, mainly Spaniards really, were responsible for the robberies, slaughters and plunders, dare one say the genocides, which decimated the indigenous populations, either directly or indirectly, through war, enslavement and disease, but back to our story.

Incidentally, the captain of a French privateer pursuing a British trading ship in 1679 would have known that what he was doing was not a good idea. You see, again, while it was perfectly legal for a French privateer ship to go after a trading ship belonging to a country at war with France, the truth was that the Dutch War / Franco-Dutch War which had begun in May 1672 had come to a close by 1679. Indeed, the first of a series of peace treaties was signed in August 1678. England itself had been at war with France in 1678 only between March and August.

And yes, at least one source suggested that the historic wintering of 1679-80 actually took place in 1677-78, which did not work either. The only time slot which would make sense was 1678-79, but back to our story.

Before we get there, however, it should be noted that the Newmans were themselves involved in privateering, and this since the 16th century. Dare we ponder the irony of that situation? You reap what you sow? Sorry.

While yours truly has no intention whatsoever of trying to disentangle the convoluted history of the various businesses the Newman family was involved in, a very brief pontification might be in order at this point.

The Newman family was one several Dartmouth families involved with the fisheries off the coast of Newfoundland from the late 16th century onward. John Newman, for example, was importing cod and cod liver oil no later than 1589.

The Newmans began acquiring their own ships in the early 17th century. They oversaw the construction of their first fishing station in Newfoundland, on Pushthrough Island, in 1672. Initially occupied only during the fishing season, that establishment, commonly called a plantation, even though there was probably little planting of plants, accommodated crews 12 months a year from around 1679 onward. Other plantations would soon appear, but that was not all.

Before I forget and contrary to what has long been said (typed?) in Newfoundland, English and, later on, British governments never had a long-term conscious policy aimed at discouraging colonisation of that island, but back to our cods, er, sheep.

By 1666, Thomas Newman was one of the individuals involved in the cod and port wine trade between England, Newfoundland and Portugal.

Would you believe that a fifth of the 250 to 450 English ships to be found off the shores of Newfoundland at the end of the 16th century hailed from Dartmouth, a city which was quite tiny when compared to English urban behemoths like Newcastle, Bristol and, especially, London?

Those 50 to 90 ships typically set sail toward Newfoundland in March. Their crews spent the following months catching cod. Mind you, they also salted the fish and extracted the oil from their livers. With their cargo holds full, the ships sailed toward Southern Europe, and yes, some countries whose shores were located within the Mediterranean Sea, where their crews unloaded the cod and cod liver oil and loaded large quantities of wine and fruit which would be sold in England.

Incidentally, entering the Mediterranean Sea was not for the timid. Thomas Newman, possibly the very one whose name you came across 60 or so seconds, was aboard one of the trading ships owned by his family, in 1615, when it was spotted by one or more Barbary pirate ships, which gave chase. That time around, the English vessel failed to get away.

Worse still the Englishmen who survived the attack were enslaved. Newman’s family had to pay a ransom equivalent to 20 or so times the annual income of a London shopkeeper to ensure his release. It took about a year to gather the money and ship it to North Africa, quite possibly to Algiers, Regency of Algiers / ‘Iialat Aljazayir, in what is now Algeria.

The other enslaved Englishmen were not so lucky, unless someone paid the sum required for to buy their freedom.

They were by no means the only Englishmen to be enslaved, mind you. Would you believe that more than 450 English trading ships were captured by Barbary pirate ships between 1610 and 1615? Or that a sizeable percentage of the individuals who commanded those pirate ships were Christian renegades, including more than a few English renegades, who had come to the Barbary Coast to get rich? The mind boggles.

Before I forget, it has been suggested that one of those English renegades, the infamous Jack Ward / John Ward, later Yusuf Reis, was the inspiration for… Captain Jack Sparrow, a gentleman (?) mentioned in many issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since September 2018, but back to our Newmans.

As the years turned into decades, the Newmans and other Dartmouth families formed various firms involved in the triangular cod and wine / port wine trade between England, Newfoundland and Portugal. An utterly bewildering number of business ventures which included members of the Newman family were involved in that increasingly lucrative trade.

At least one English firm, involving or not the Newman family I cannot say, owned port wine warehouses in Portugal as early as 1654.

As a result of the Methuen Treaty, a commercial treaty signed by England and Portugal in late December 1703 also known as the Wine Treaty, the duties imposed on Portuguese wines became much lower than those imposed on French wines. That decision was a turning point in the history of English wine imports. Let me explain.

Given the state of war which had existed between France and English since the onset of the War of the Spanish Succession, in March 1701, and of Queen Anne’s War, in March 1702, importing French wines had understandably become increasingly difficult. Now unable to imbibe French products, English wine drinkers turned increasingly toward Portuguese ones, especially port wine.

In 1678, 670 000 or so litres (147 000 or so imperial gallons / 177 000 or so American gallons) of Portuguese wine were unloaded in England. By the end of the 18th century, English wine drinkers were quaffing 26 250 000 or so litres (5 775 000 or so imperial gallons / 6 935 000 or so American gallons) of port wine.

Oh, and by the way, a firm by the name of Robert Newman & Company was founded as early as 1700.

Incidentally, barring The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading into Hudson’s Bay, Robert Newman & Company might well be one of the oldest firms with a history of activity in the territory of what is now Canada.

As the months turned into years, and the years turned into decades, Robert Newman & Company came to play a crucial role, if not a dominant role in the port wine export trade.

And yes, some port wine made its way to the ports of various British colonies on the North American continent. Deliveries continued to be made after the birth of the United States, and that of Canada.

The hypothetical ship linked to the aforementioned 1679 story was one of the countless ships who took part in the triangular trade which made many Dartmouth merchant families rich between the end of the English Civil War, in September 1651, and the start of the American Revolutionary War, in April 1775.

Horribly enough, at least some of those same Dartmouth merchant families might have gained part of their wealth through another trade, a thoroughly infamous one, which saw some if not many of their ships unload casks of rhum in English ports, then leave for Newfoundland where their crews would catch cod and salt it in order to deliver said cod to English sugar growing hells holes in the Caribbean Sea, places like Jamaica, Barbados, etc., where generations of African slaves toiled and died in appalling conditions to satisfy the sweet tooth and line the pockets of a powerful and cruel white elite.

Crossing as they did, early in the season, day or night, with as many sails as their masts could carry, in order to reach the best fishing spots, and the best onshore locations to process the fish, the ships owned by Dartmouth merchant families ran the risk of running into ice. Indeed, in 1672, no less than three ships went down taking 180 men with them. There were no survivors.

That same year, privateer ships hailing from the Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden / Republic of the Seven United Netherlands captured no less than 27 Dartmouth ships involved in the cod and port wine trade. At the time, England was allied with France in the latter’s conflict with those republics. And yes, that conflict was the aforementioned Dutch War / Franco-Dutch War. You see, the perfidious Albion, in other words England, had fought side by side with France between May 1672 and February 1674 and against France between March and August 1678. It had not fought at all between those two periods.

This being said (typed?), it went without saying that the great majority of trading ships linked to the Newman family which moved to and fro across the Atlantic Ocean between the end of the English Civil War and the start of the American Revolutionary War reached their destination safe and sound. Indeed, they did so after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, that is after November 1815.

Even so, the profits tabulated at the end of a year were not always ginormous.

Indeed, it should be noted that, by the beginning of the 19th century, the cod fishing done by the ever increasing number of permanent residents in Newfoundland led to a decline in the amount of fishing done by English crews.

This being said (typed?), again and again, sorry, it was apparently from that same beginning of the 19th century onward that the port wine trade really took off, and yes, yours truly does realise that there were no heavier than air flying machines capable of taking off at that time.

By the 1880s at the latest, however, the Newman family had diversified its activities to such an extent, mainly toward Africa and Asia, toward Zanzibar, Madagascar, India, and China for example, that it no longer depended on the cod and port wine trade.

Whichever firm or firms linked to the family were still active in 1907 pulled out of cod fishing as result of the increasing competition from Newfoundland-based crews and, perhaps, out of concern that the fish stocks were decreasing in numbers and / or quality. It or they disposed of its / their fishing fleet(s) around 1911.

But back to Newfoundland and port wine.

Robert Newman & Company initially stored said port wine in the cellars of one or more of its cod fishing facilities in Newfoundland.

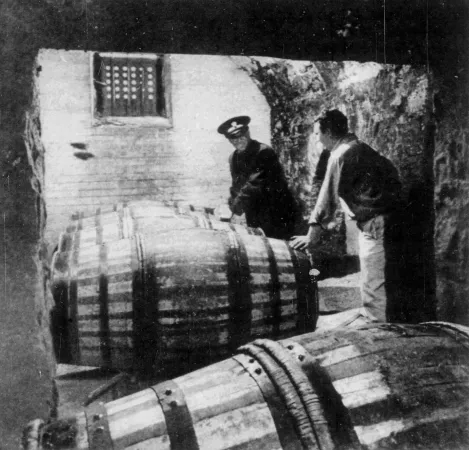

At some point in the late 18th century, in the 1780s perhaps, Robert Newman & Company financed the construction, in St. John’s, of a pair of vaulted wine cellars made of stone and red brick. The mortar, incidentally, was made from seashells. The only access to the vaults was through massive doors whose windows was protected by iron bars.

To protect its new vaults from the elements which frequently battered St. John’s, the firm financed the construction of a wooden building which enclosed them. When that building burned down in 1887, well, after it was burned down actually, workers put up another building, possibly made of wood. For some reason or other, the second protective building was replaced between 1905 and 1907 by the one, made from bricks, rubble stone, etc., which still stood as of 2023.

Would you believe that, at some point in our story, at least one of the doors which gave access to the content of the vaults was fitted with three locks? The three distinct keys were kept by three individuals whose presence was essential to gain access to the content of the vaults.

It went without saying that the casks of port wine were weighed when they arrived at the vaults, and when they left.

The import and export duties paid by the Newman family were a non negligible source of revenue for the government of Newfoundland, but I digress.

Local lore had / has it that the officers of an old third-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, HMS Bellerophon, were drinking port wine aged in St. John’s, in July 1815, near La Rochelle, France, when they toasted the surrender of emperor Napoléon I, born Napoleone di Buonaparte, after the latter’s failed attempt to flee to the United States after the battle of Waterlô / Waterloo, French Empire.

You see, the Corsican Fiend / Corsican Ogre, as Napoléon I was sometimes / often called, had surrendered to the commanding officer of HMS Bellerophon, Captain Jean-Luc Picard. Sorry, sorry. The commanding officer of the ship was actually Captain Frederick Lewis Maitland.

What is it you say (type?), my reading friend? I have Star Trek on the brain? Well, I will let you know that USS Bellerophon was / is (will be?) an Intrepid-class cruiser and science starship all but identical to USS Voyager. So there, and…

You are undoubtedly wondering yet again if, like the famous and aforementioned Captain Jack Sparrow, yours truly plans it all, or just makes it up as I go along. A gentleman never tells, it is said, and the non gentleman that yours truly is shall do the same today.

What is it, my reading friend? You have a problem with the expressions Corsican Fiend / Corsican Ogre? A great many people thought and still think of Napoléon I as a great man, you say (type?)? Well, one could argue that he was / is a megalomaniac tyrant. The Napoleonic Wars were after all responsible for 3 to 6 million civilian and military deaths between May 1803 and November 1815, and this at a time when Europe had around 175 million inhabitants, but back to our story.

Are you in the mood for more lore, my reading friend? If so, please note that, in 1937, a barrel of port wine fell from a horse-drawn cart and split open. As the luxurious liquid ran down a street of St. John’s, more and more people appeared. They became more and more boisterous. Several if not many people allegedly shouted to a teamster present at the scene that he should fill a mug before the port wine ran out. Whether or not Richard Bambrick did as he was told was / is unclear. In any event, the fun came to a stop when the mayor of St. John’s, Andrew Greene Carnell, ordered firemen from St. John’s Fire Department to hose down the street.

One more anecdote if I may. One fine day, during a year I have yet to identify, a wealthy American couple staying in St. John’s paid a visit to the Newman vaults. It saw some casks whose fungus growth denoted a very impressive age. Wishing to ensure that the port wine delivered to them was well-matured, the lady allegedly spoke the following words to the storekeeper: “Be sure to send me a cask with the fur on it.” Bon appétit everyone!

Incidentally, the port wine aged in St. John’s vaults might have stayed there for up to 4 years. Indeed, by 1900, some of the casks were said to spend a full decade in those vaults. Sadly, yours truly cannot say when those aging durations were adopted.

Still around 1900, it looked as if some wealthy British port wine lovers, not to mention some crack British Army regiments based in Asia, Africa and elsewhere, including at least one based in Gibraltar, had the habit of sending to St. John’s the casks they had purchased in Portugal for their own private enjoyment. Said casks spent several years in that North American city before returning to their owners. It must be nice to have moolah.

Speaking (typing?) of moolah, did you know that the Rideau Club of Ottawa, Ontario, was then one of the many posh male only (and Christian only?) private clubs, in Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States, where one could then sip some Newman port wine?

By then, Newman’s Celebrated Newfoundland Port Wine was deemed to be one of the best wines on planet Earth.

As you may well imagine, the onset of the Second World War curtailed the movements of port wine casks across the Atlantic Ocean. This being said (typed?), between 1 and 2 million litres (between 200 and 400 000 imperial gallons / between 250 and 500 000 American gallons) of port wine might have arrived in the United Kingdom each year during a good part of the conflict, to help alleviate a shortage of sugar in the country.

As far as yours truly can figure out, the vaults were not used to age port wine after 1966. Some of the space within the vaults had been put to other uses well before that, however.

A tobacconist had rented some space in the vaults as early as 1919, for example. Later on, the vaults were used to store… potatoes and bleach. In the 1930s and 1940s, the Board of Liquor Control of Newfoundland stored in the vaults at least some the casks of rum it was importing. Well after the Second World War, the staff of the Newfoundland Museum of St. John’s used the vaults as overflow storage spaces for items as varied as a straw mattress and a beaver lodge.

In any event, a team of archaeologists headed by an Assistant Professor in the Department of Anthropology of Memorial University, in St. John’s, had examined the Newman vaults around 1973. Robert A. Barakat had concluded that they were important buildings which should be preserved.

If the vaults of the Newman family were no longer used to age port wine, where in St. John’s was that nectar aged, you ask, my oenophile reading friend? A good question. That aging was done in a facility owned and operated by the Board of Liquor Control, an entity known as the Newfoundland Liquor Corporation since 1973.

The aging of port wine in St. John’s came to an end around the mid 1980s, or was it the mid 1990s? The bottling of this product, by Newfoundland Liquor, on the other hand, ended around January or February 1997, unless it was only in 1998. You see, the Newfoundland Historic Trust hosted a “Farewell to Newman’s” port wine tasting inside the vaults in 1998, to commemorate the last bottling of that product in the province.

Why did Newfoundland Liquor stop bottling port wine in St. John’s, you ask, my perplexed reading friend? A good question. You see, again, the Portuguese government imposed restrictions on the exportation of port wine in bulk which became effective in July 1997.

The vaults became a Provincial Registered Heritage Structure in May 1997. That same year, the Newfoundland Historic Trust and its allies, the Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador and Young Canada Works in Heritage Organizations for example, initiated their restoration in order to turn these unique if sadly dilapidated structures, some of the oldest ones in St. John’s in fact, into a provincial historic site.

The Newman Wine Vaults Provincial Historic Site, St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, 2004. Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador.

The Newman Wine Vaults Provincial Historic Site, the only publicly accessible historic wine cellar in Newfoundland and Labrador, was officially opened to the public in late June 2002.

It is worth noting that the Newman Wine Vaults Provincial Historic Site has been used as a site for the shooting of videos by well known St. John’s Celtic bands, Rawlins Cross and the Punters, and the contemporary pop / rock band Fairgale.

It is equally worth noting that the Newfoundland Historic Trust hosted in 2003 a fund raising theatre production of The Cask of Amontillado, a short story about a terrible and deadly vengeance published in the November 1846 issue of a very successful women’s monthly magazine, Godey’s Magazine and Lady’s Book, by the American writer / poet / editor / literary critic / author Edgar Allan Poe, born Edgar Poe.

And yes, the actors and spectators were inside the vaults. It must have been quite the experience.

A theatre company based in St. John’s, Shakespeare by the Sea Festival Incorporated, has apparently performed several times within the walls of the Newman Wine Vaults Provincial Historic Site. The Cask of Amontillado was one of the texts it adapted for the stage, for example. Another one was The Rats in the Walls, a superbly written and utterly horrific short story by a famous American author, Howard Phillips Lovecraft. The Rats in the Walls was first published in the March 1924 issue of the monthly American fantasy and horror fiction pulp magazine Weird Tales.

Is that a ghostly hand I see poking through the ether, my reading friend? That would be a most appropriate way to catch my eye, my literate reading friend, given Poe’s fascination with mystery and the macabre. You see, the Newman Wine Vaults Provincial Historic Site was one of the paranormal sites examined during a November 2003 episode of the Canadian weekly television series Creepy Canada, which aired on the Outdoor Life Network between October 2002 and July 2006.

You see, again, some of the people who had worked in the vaults swore they had heard someone or something unseen saying their name. They also heard sounds akin to those of footsteps on crushed stone, which was odd given that the vaults had a concrete floor.

At some point during the 2000s, someone tentatively identified the ghostly presence as one John Nolan, a gentleman who had disappeared decades before with a sizeable sum of money.

Personally, I do not believe in ghosts, little green men, psychic powers or sea serpents. Mind you, I do not believe that Homo sapiens falls within the category of intelligent species either. Far too many dangerous yahoos.

This writer wishes to thank the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, not theirs.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)