As the world, err, as the wheel turns; Or, How / why SS Klondike, a cargo-carrying sternwheeler river boat briefly used for river cruises, became one of Parks Canada’s 1,004 national historic sites, part 3

Welcome back, my reading friend, and… I know, I know. I pledged several moons ago to strive toward brevity. It is just that this story of SS Klondike, a cargo-carrying sternwheeler river boat, river cruise ship and national historic site, is really quite interesting. And I see you nodding in agreement. Yes, yes, you did. Do not deny it.

In any event, by November 1959, rumours, accurate rumours as it turned out, circulated to the effect that Canada’s Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources had agreed to take on responsibility for no less than 4 of the old sternwheeler river boats formerly operated on the Yukon River by British Yukon Navigation Company Limited. Said river boats would become tourist attractions. Indeed, the minister of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources, Francis Alvin George Hamilton, indicated that one of the ships would be restored and turned into a museum, adding that he would be pleased if business interests acquired another vessel for use as cruise ship on the Yukon River, between two municipalities of the Yukon Territory, Whitehorse and Carmacks.

As the risk of sounding impertinent, the protests of the inhabitants of Whiskey Flats, the poor neighbourhood where SS Klondike was scheduled to go, First Nations people in most cases, went utterly unheard when said neighbourhood was taken over by the city of Whitehorse (and the federal government?) between 1962 and 1967 and, to a large extent, bulldozed. Said inhabitants had no choice but to move, or be moved, to parcels of land which were by no means always suitable.

If yours truly may be permitted to quote, out of context, a sentence taken from the great novel Allah is not obliged, published in French in 2000 by the great Ivorian writer and athlete Ahmadou Kourouma, there is no justice on this Earth for the poor. And if you happened / happen to be poor and Indigenous, chances are you will end up federally, municipally, provincially and territorially scr*w*d, but back to our story.

By June 1964, 3 of the 4 sternwheeler river boats that the Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources had agreed to take on responsibility for were still on the shores of the Yukon River and… Three, you ask, my puzzled reading friend? Yes, three. You see, SS Keno had sailed from Whitehorse to Dawson City, Yukon Territory, in late August 1960 where it was carefully hauled out of the Yukon River. SS Keno, a sternwheeler river boat built in what was then White Horse in 1922, was designated as a national historic site in May 1962. It was still with us as of May 2023. You can visit it if you so desire, as long as you show up between the months of May and September.

How about SS Klondike, you ask? That riverboat was / is after all at the heart of this issue of our mind blowing blog / bulletin / thingee. Well, its continued presence on the shores of the Yukon River was at the origin of an aggrieved editorial published in June 1964 by Whitehorse Star, the only newspapers in… Whitehorse. Rumour had it that it would be moved to its final resting place, at Whiskey Flats, around 1967. The problem with that far far away date (Hello, Shrek! Hello, Princess Fiona!) was that, in winter time, homeless people made camp under or inside one or more of the old river boats. Understandably enough, some of them started fires to keep warm. To that risk of accidental fire, one had to add the fact that a small fire had been very recently and deliberately set in one of the river boats. That fire was quickly doused.

All in all, the Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources and its Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada were darn lucky that none of the old river boats had burned down. They needed to act in 1964, concluded the editorial, before some disaster struck.

That frustration was in full view in August 1964 when the minister of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources, Arthur Laing, visited Whitehorse. What form did that frustration take, you ask? Well, Laing and his entourage could hardly miss the large sign placed on SS Klondike which said, and I quote, “Please Arthur, take me to my new home.”

In early 1965, the Commissioner of the Yukon, Gordon Robertson Cameron, stated that a river boat, either SS Klondike or the slightly smaller SS Casca, would be moved to a park-like setting in the spring of that same year. That ship would be restored later on.

By March, none of the old river boats had moved. Indeed, no sign of movement was being planned, and the level of frustration within certain Whitehorse circles, including the Whitehorse Chamber of Commerce, was rising. The editorialist of Whitehorse Star could also be counted among those frustrated individuals.

Said individuals frankly did not care which of the two river boats got moved. They only wanted the Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources and its Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada to wake up and do something.

The caption of the following (prophetic?) editorial cartoon relayed some of the frustration felt within certain Whitehorse circles regarding the passivity of the Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources and its Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada: “… And by Saturday we’ll be able to float it down main street.”

An editorial cartoon which relayed some of the frustration felt, in early 1966, within certain Whitehorse circles regarding the passivity of the Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources and its Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. Anon., “–.” Whitehorse Star, 11 March 1965, 6.

The department finally woke up in late August, with an early September announcement to the effect that SS Klondike would be moved to a site at Whiskey Flats, just south of the Robert Campbell Bridge in order to become a national historic site. A sizeable sum of money would be spent to restore the ship and create a northern transportation museum within its hull.

Interestingly, the terms of the bid prepared by the Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources and certain issues in late December 1965 seemingly suggested that the move of SS Klondike would take place in wintertime – or in very early spring. That plan soon went right out of the window, however.

You see, the department’s decision to move the ship had not gone unnoticed. Realising that the move it had not expected to take place might actually take place, the Yukon Historical Society publicly opposed said move in a newsletter, and this in late February or early March 1966.

The Yukon Historical Society stated that SS Klondike should remain where it was, at the shipyard of defunct British Yukon Navigation, with the other two sternwheeler river boats accepted by the Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources which were still there, SS Casca and SS Whitehorse. Said shipyard was well worth preserving, at least in part. “Why should the least interesting of the three paddle-wheelers be getting all the attention,” asked the society? Indeed, it feared / alleged that the foreseen move foresaw the destruction of SS Casca and SS Whitehorse.

The newsletter of the Yukon Historical Society did not go unnoticed. It seemingly surprised, and not in a good way, the people who were pushing for the move, including the leadership of the aforementioned Whitehorse Star, which feared that division within the people of Whitehorse might scuttle the move of SS Klondike.

At a special meeting requested by the Yukon Historical Society and held in early March, the Whitehorse Chamber of Commerce politely refused to support its effort to delay the move of the ship. It would, however, support any effort made to preserve SS Casca and SS Whitehorse. In turn, the society indicated it would not oppose the move of SS Klondike if someone guaranteed that the other two sternwheeler river boats would not be destroyed.

A few days later, Laing indicated that no decision on the move of SS Klondike would be taken for another two weeks. By then, that is in late March, the Minister of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources would be in Whitehorse to take part in the second Northern Resources Conference held in that city over the years. Laing’s presence in Whitehorse would allow him to get a clearer picture of the issues surrounding the move of SS Klondike.

The concerns / fears expressed by promoters of the move were confirmed when, in mid-March, after taking into consideration a brief submitted by the Yukon Historical Society, the Council of the Yukon Territory passed a motion, by a vote of 3 to 2, asking Laing to reconsider the move of SS Klondike. The council members who had voted against the motion were upset, if not outraged by the fact that the Whitehorse Chamber of Commerce had not been given a chance to present its view. Indeed, said chamber had allegedly been advised not to submit the brief it had prepared. The mind boggles.

The leadership of Whitehorse Star utterly disapproved of the position taken by the Yukon Historical Society. An industrial site like the one surrounding the sternwheeler river boats was no place for a tourist attraction. A March 1966 editorial from the newspaper is worth quoting here, if only in part:

If the Historical Society wants a bandwaggon [sic] to climb on, if they are so deeply concerned about our historical resources, why are they standing silently by while Edmonton walks off with not just a riverboat, but the whole Klondike theme?

Why are they not protesting to John Fisher of Expo ‘67 that Edmonton has no right to a permanent Klondike building at the Centennial Exposition? There’s one they can really get their teeth into!

For your information, John Wiggins “Mr. Canada” Fisher was the Commissioner of the Centennial Commission, the organisation created in January 1963 to ensure that Canada’s centennial, in 1967, would be celebrated across the country.

Why was the editorialist angry at Edmonton, Alberta, you ask, my placid reading friend? Well, you see, in March 1966, the Edmonton City Council began to look into the possibility of financing the construction of a Klondike pavilion on the site of the Exposition internationale et universelle de Montréal, or Expo ‘67, which was to take place from April to October 1967, in… Montréal, Québec, an amaaazing world fair mentioned in several / many issues of our tremendous blog / bulletin / thingee since November 2020.

A lot people in the Yukon were outraged, and rightly so, by what they saw as a shameless attempt to steal their history. Many individuals and groups sprang into action. Laing himself supported them, slamming the Edmontonian Goliath for its attempt to usurp part of the history of the Yukonian David.

In late April, a Council of the Yukon Territory delegation met with Expo ‘67 officials in Montréal and seemingly received some sort of assurance that Edmonton’s Klondike pavilion would never see the light of day. In the end, it did not. There would, however, be an area known as Fort Edmonton / Pioneerland. That area was located at La Ronde, the vast amusement park of the fair.

Fort Edmonton still existed in some form at least until the mid-2010s. La Pitoune, a famous ride located therein, remained in operation until the end of the 2016 season, but I digress.

By the way, did you know that La Pitoune was one of the 70 or so log flume type rides delivered between 1964 and 2001 by one of the most famous ride makers of that period, an American firm by the name of Arrow Development Company Incorporated, and its successors, Arrow Huss Incorporated and Arrow Dynamics Incorporated?

In the end, again, the last minute hand wringing of the Yukon Historical Society did not scuttle the move of SS Klondike. Better yet, the Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources indicated that SS Casca and SS Whitehorse would be preserved until a better spot could be found for them. Mind you, it is possible, I repeat possible, that the department returned ownership of these old sternwheeler river boats to their previous owner, White Pass & Yukon Corporation of Vancouver, British Columbia.

The big move of SS Klondike began on 21 June 1966, I think. And yes, said move took place through the streets of Whitehorse, all the way to Whiskey Flats. I kid you not. As hundreds of local residents looked in astonishment – and took the first of countless family photographs and films. And here is proof. Err, a second proof actually, given that the photograph at the beginning of this third part of our SS Klondike article also showed a stage of the old sternwheeler river boat’s journey through Whitehorse.

The sternwheeler river boat SS Klondike at a relatively advanced stage of its journey to Whiskey Flats South. Anon., “– .” Whitehorse Star, 30 June 1966, 1.

The individual in charge of the move, Charles “Chuck” Morgan, kept a close eye as his team carefully moved the 64 metre (210 feet) long sternwheeler river boat, which weighed a great many hundreds of tonnes (tons), onto a cradle of steel beams / girders which had initially been part of the Peace River Bridge, near Fort Saint John, British Columbia, a bridge which had partly collapsed in October 1957 before being demolished and replaced.

Said team then placed large wooden planks / beams in front of the ship. It also secured heavy steel cables to SS Klondike. Said cables were then attached to the powerful bulldozers (2 to 4?) which pulled the ship in its cradle. A mechanical fork lift stood at the ready to pick up the wooden planks left behind as SS Klondike slowly moved across them and put said planks back in front of the strange procession.

Did I mention that 8 or so metric tonnes (8 or so Imperial tons / 9 or so American tons) of slightly dampened soap flakes were spread on the wooden planks to facilitate the agonisingly slow movement of said procession? I kid you not.

Need I add that many of the good people of Whitehorse hoped that the city would not be drenched by rain for many days? Mind you, some mischievous young people might have hoped that such a downpour would occur. After all, that much soap would have created a ginormous amount of soap suds, but I digress. Gleefully, I will admit. Yours truly, after all, sometimes feels (behaves?) like a superannuated kid. (Hello, EP!)

And yes, multiples power and telephone lines had to be temporarily taken down as SS Klondike regally proceeded through Whitehorse.

The old sternwheeler river boat / cruise ship reached its final resting place, above the bank of the Yukon River, on… 16 July. I kid you not. The journey made over a distance of less than 2 kilometres (less than 1.25 mile) had seemingly taken 26 or so days. The site in question was south of the Robert Campbell Bridge, where the southern half of Whiskey Flats used to be.

How about the northern half of Whiskey Flats, you ask, my preoccupied reading friend? Well, White Pass & Yukon Railway donated land it owned there, north of the bridge, to the city of Whitehorse. At some point after the move of SS Klondike, the Whitehorse branch of the gigantic American service organisation Rotary International Incorporated was given permission to proceed with a project it had proposed. A park was thus created, a park to be known as… Rotary Park. Said park was seemingly opened to the public in 1970.

On 16 July 1966, or was it two days later, the impressed and grateful mayor of Whitehorse, Howard W. Firth, presented Morgan with a miniature reproduction of S.S. Klondike, in gold no less.

SS Klondike was formally recognised as a national historic site in June 1967.

The second and last move of SS Klondike. Anon., “–.” Whitehorse Star, 10 April 1974, 1.

In April 1974, SS Klondike left its final resting place for a new one, closer to the Yukon River, which provided a more authentic setting. Despite some damage to one of the support beams of its sternwheel, the ship was welcoming visitors no later than June.

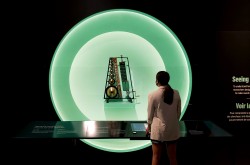

Not too, too long after, a team of historians, curators and conservators began to work on the transformation of SS Klondike into a museum. It acquired, conserved and restored a great many artifacts and ordered a great many reproductions. It gathered a great many historical photographs and documents. It also interviewed a great many people, including former crew members. Thousands of artifacts, photographs and reproductions were put on panels and in display cases aboard SS Klondike during the spring and very, very early summer of 1981.

Yours truly inserted the words very, very early summer because decades of experience in the museum business tell me that, all too often, museum big enchiladas underestimate the amount of time needed to prepare an exhibition. (Hello, Z, Y, X and many other big enchiladas!) On more than one occasion, the members of an exhibition team went out of an exhibition area after cleaning up the display cases at precisely the moment a proud director general was welcoming various dignitaries before entering said exhibition area, but I digress. (Hello, SB, EG, EP and many other people!)

The dedication ceremony of the thoroughly spruced up SS Klondike took place on 1 July 1981. The ship had been brought back to the way it looked between 1937 and 1943.

Several former crew members of SS Klondike were present that day, including its captain during its cruise ship days of 1954-55, William J. “Bill” Bromley. That was nice gesture, if I do state so myself.

As was hoped by the promoters of the move, SS Klondike became a major tourist attraction, which was / is nice given the huge amounts of money spent in over the past 40+ years to keep it looking as spick and span as possible. It will indeed be impossible visit the ship during the 2023 season due to ongoing restoration work.

Why is that, you ask, my puzzled reading friend? You see, having hundreds of thousands of people walk all over SS Klondike’s decks over years and years put a lot of stress on its structure. Add to that wind, sunlight, snow, rain, hail, bird droppings and idiotic Homo sapiens who believe that barriers and “Please Do Not Touch” panels do not apply to them, or their brood, and you have a recipe for serious deterioration.

You might be surprised / shocked, or not, to learn that the introduction of electric fences and / or cattle prods on museum floors was suggested at least once in my presence in past decades, I think, sarcastically of course, but I digress.

By the late 1990s, there so many leaks that plastic sheets were placed over the bedding and artifacts in many staterooms of SS Klondike. Buckets also had to be put to use. As you may well imagine, all of that water was affecting the integrity of the hull. Some of the wooden beams had become so soft that it proved possible to ram a screwdriver right through them. According to some, SS Klondike’s bow section was on the verge of collapse.

A massive restoration project began in 1999. It would last 6 or so years. The plan was to keep as much of the original wooden structure as possible. Even so, a good part of the planks and ribs of the hull, as well as a good part of the decking, had to be replaced. The sternwheel itself was rebuilt. The team used the opportunity it was granted by the restoration project to install a dry sprinkler system aboard SS Klondike.

A sprinkler system, you ask, my concerned reading friend? Had anything bad happened? Well, in June 1974, the concerns expressed many times by many people had come all too true. The two old sternwheeler river boats stored on the shores of the Yukon River, SS Casca and SS Whitehorse, caught fire. Hundreds of people soon gathered at the site. Some / many of them had tears in their eyes. Both ships were destroyed.

No one was injured in the blaze but 3 young persons who had spent the night before the fire on SS Casca, where said fire had broken out, and who had to be rescued by firefighters, were briefly detained. These young persons soon found themselves at the receiving end of a surprising and disturbing amount of venom.

And so this story ends. Err, well, actually, the saga of SS Klondike is far from over. That national historic site will continue to delight countless people from across the globe for decades to come.

This writer wishes to thank the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, not theirs.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)