Plough, plough, plough your field; Or, How two brothers, Harry Thomas Raser and George Bernard Raser, Junior, used an automobile on the family farm, near East Ashtabula, Ohio, in 1903

Have you ever had the misfortune of being roused from a peaceful slumber by a rambunctious rooster, my reading friend? […] Me neither. This being said (typed?), the topic the two of us will examine today will touch upon farming. Better yet, that topic will combine fields of study of two national museums of Canada located in Ottawa, Ontario: the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum and the Canada Science and Technology Museum.

Let us initiate our look at the topic at hand with some context, shall we? Yours truly shall be brief and… Who dared to laugh? Who? Who??

Anyway, let us begin.

One day in early May 1903, the superintendent of the Erie, Pennsylvania, iron ore docks, leased docks apparently, of M.A. Hanna & Company, an important firm with interests in iron ore, coal mines and blast furnaces, visited some relatives near East Ashtabula, Ohio, including of course his widowed mother, Harriet Vance Raser, born Maus. Indeed, Harry Thomas Raser spent the night at the family farm.

Raser had driven all the way from Erie, his place of residence, thus covering a distance of 65 or so kilometres (40 or so miles) along the southern shore of Lake Erie, which was quite an odyssey considering the likely condition of the road and the uncertain reliability of an early 20th century automobile.

To answer your question, Raser was born in July 1870. That mechanically inclined person was therefore 32 years old in May 1903.

And no, my ever-curious reading friend, yours truly does not know which type of automobile Raser was driving. Had he flown to East Ashtabula, I believe I might have been able to identify the type of aeroplane used. Automobiles, however, are a mystery to me.

And yes, yours truly knows full well that not one powered aeroplane on planet Earth had made a controlled and sustained flight as of May 1903.

All I can say (type?) is that the “powerful” 4-seat gasoline automobile in question tipped the scales at 725 to 815 or so kilogrammes (1 600 to 1 800 or so pounds). The powerful engine of that automobile produced an astonishing 4.5 imperial horsepower (4.6 or so metric horsepower / 3.6 or so kilowatts). (Hello, EP!)

The vehicle in question was not the first automobile Raser had driven or owned. Nay. He was said to be familiar with steam and electric automobiles, as well as gasoline automobiles, and…

All right, all right, keep your hubcaps on. Raser’s automobile might, I repeat might, have been a Mark VIII Columbia gasoline tonneau made by an American firm, Electric Vehicle Company. Yours truly based that possibility by the fact that Raser was trying to sell two automobiles of that type as well as an otherwise unidentified automobile made by another American firm, Locomobile Company of America, no later than July 1903.

To answer the question the puzzled look on your pretty little face is hinting at, a tonneau was / is, I think, an automobile whose passenger compartment was / is open to the elements.

In any event, the morning after his arrival in East Ashtabula, Raser, his 20-year-old brother, George Bernard Raser, Junior, and their mother saw that the dried-up grass near a nearby railroad track, a railroad track operated by New York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad Company, was burning. Sparks from one or more passing trains were to blame.

Fearing that the fire might spread onto a meadow on the north side of the family farm, the Raser brothers decided to create some sort of fire break. The catch was that it would take time to prepare a team of horses. Too much time, perhaps. The came the lightbulb moment. Using a chain, the brothers hitched a plough to the rear axle of the automobile owned by the older Raser brother. Said brother drove that vehicle while his younger sibling stood behind the plough, holding its handles. The ploughing of the chosen section of the meadow went swimmingly. Indeed, the automobile did the job a lot faster than a typical team of horses could have done it.

Would you believe that the younger Raser found it difficult to move fast enough to keep up with the plough? The very speed of the automobile, 8 or so kilometres/hour (5 or so miles/hour), I think, proved problematic, however. You see, it could not be driven slow enough to properly plough the meadow, the way a field would have been. Even so, the automobile and its plough did well enough to prevent the fire from spreading.

As quickly as the Raser brothers had ploughed that meadow, there was still time enough for people travelling to and fro on a nearby road to slow down and stop to watch them at work. There were farmers going to Ashtabula to deliver their products. There were cyclists. There were even some people from Ashtabula who had heard about the goings on and wanted to see what was going on. None of those people had ever seen an automobile pulling a plough.

And yes, at last one newspaper stated that the experiment conducted by the Raser brothers could be duplicated by farmers who had fields in need of ploughing. Well off farmers who could afford to buy and operate an automobile, of course. According to at least one newspaper article, and I quote, “The Automobile May Revolutionize Agriculture.”

Harry Thomas Raser seemingly returned to Erie on the very day of the ploughing experiment. He did so with his younger brother. Actually, the two of them drove to Erie and returned to East Ashtabula before the day was over, thus covering a distance of 130 or so kilometres (80 or so miles), which was quite an odyssey considering the likely condition of the road and the uncertain reliability of an early 20th century automobile.

Would you believe that Harry Thomas Raser frequently covered distances of up to 240 or so kilometres (150 or so miles) in a single day in one of his automobiles? Wah!

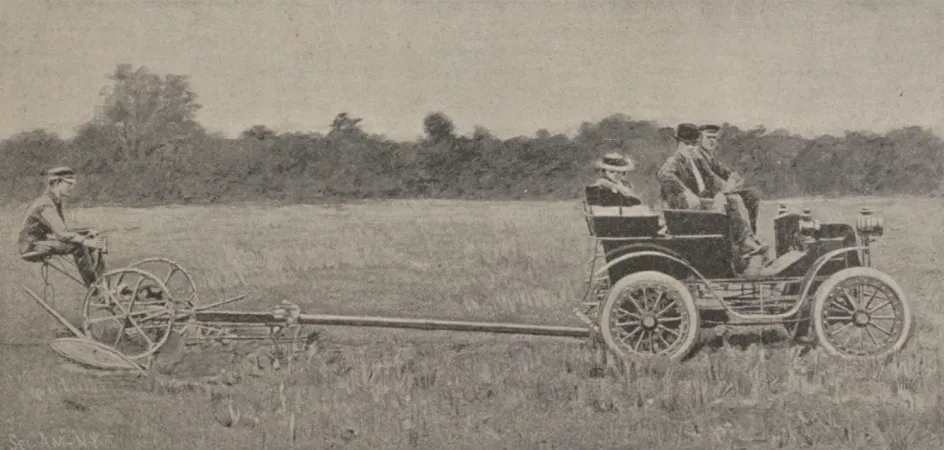

Incidentally, a few days later, the Raser brothers hitched a mower to the rear axle of the automobile used to pull a plough. Harry Thomas Raser drove that vehicle while his younger brother sat on the mower. They mowed 0.4 to 0.6 or so hectare (1 to 1.5 or so acre) of grass in one third of the time a team of horses would have needed. The very speed of the automobile once again proved problematic. You see, again, it could not be driven slow enough to properly mow the field.

And yes, the photograph at the beginning of the fascinating article you are perusing right now showed such a mowing, probably done for the benefit of the press.

Enthused by what had taken place, the Rasers allegedly had a brief chat. “We auto-mow the lawn now,” allegedly stated the older brother. “No, allegedly stated his younger sibling, I hear a horse laugh. Let’s quit.”

This being said (typed?), the Raser brothers might, I repeat might, have been sufficiently pleased with the results of their mowing experiment to continue to use the automobile for that purpose.

Mind you, they also used it to haul logs placed on a sled, at least once, and this no later than June 1903.

Did people travelling to and fro on the road near the Raser farm take the time to stop in order to watch the brothers at work, you ask, my reading friend? A good question. That is indeed very possible and…

How can I be sure that logs were indeed hauled, you ask, my sceptical reading friend? Simply because a photograph of that experiment has survived. And here is a newspaper page on which it could be found.

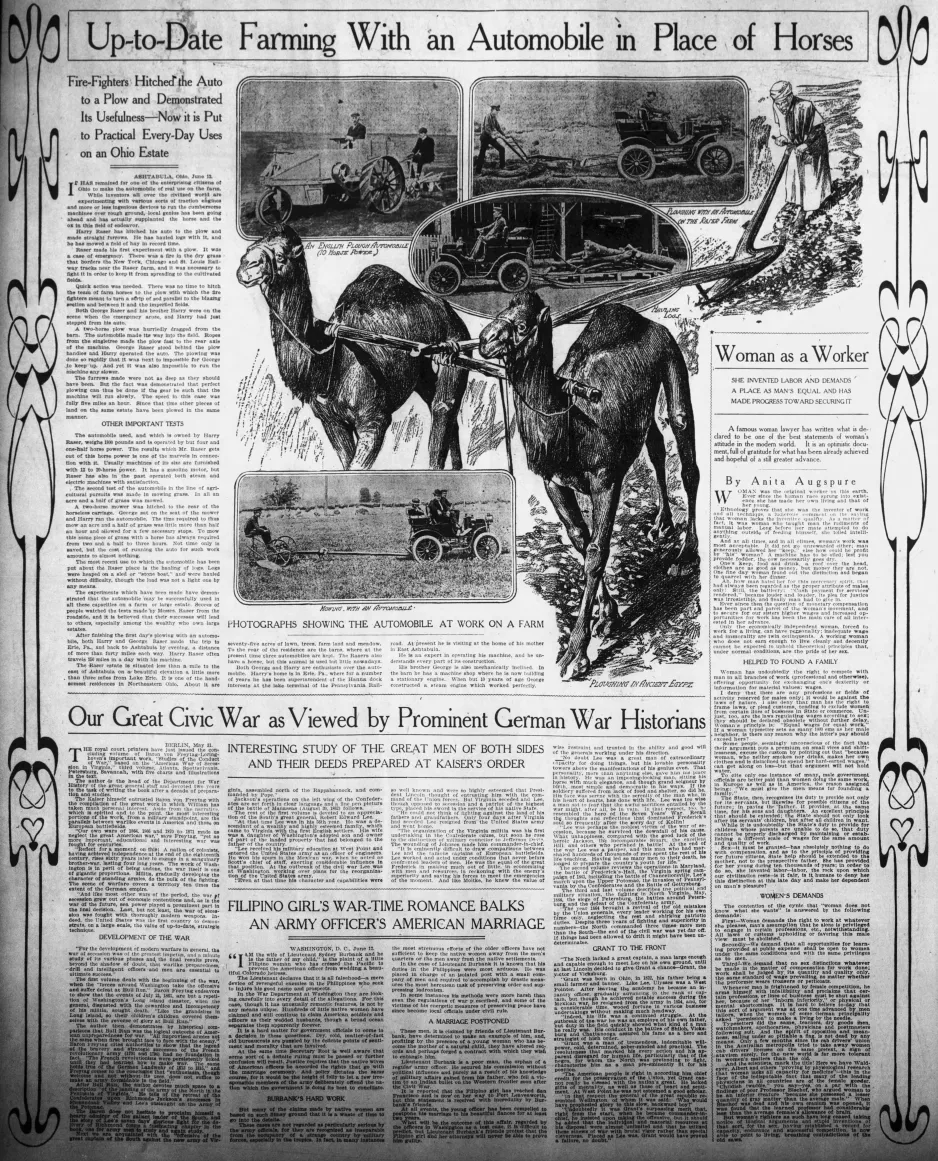

A most interesting article on automobiles and farming with the three known photographs of the experiments (ploughing, mowing and hauling) conducted by the Raser brothers. Anon., “Up-to-Date Farming With an Automobile in Place of Horses.” The Buffalo Sunday News, 14 June 1903, no page number.

Before I forget, George Bernard Raser, Junior, was as mechanically inclined as his older brother. Would you believe that, back in 1893 or so, when he was but 10 years old, that young person had seemingly put together a small, fully functional steam engine? In May 1903, he was busy building a full scale one, presumably for use on the family farm.

Would you believe that, over a period of only 2 months after the day of the initial experiment performed by the Raser brothers, at least 40 American newspapers from 24 states published an article on what had been accomplished? Oddly enough, few of those articles mentioned the grass mowing and log hauling. Information on those aspects of the work done in East Ashtabula could nonetheless be found in a few newspaper articles, or else in magazine articles.

Incidentally, at least a dozen newspapers in New Zealand published a snippet about the Raser brothers in 1903. A few more snippets were published in Australia and England during that same year.

Oddly enough, the experiments carried out by the Raser brothers seemingly did not catch the eye of newspapers published in Canada, and this despite the fact that this country and the United States shared and still share the longest undefended border on planet Earth (8 890 or so kilometres (5 525 or so miles)).

The experiments carried out by the Raser brothers did, however, catch the eye of an otherwise unknown Frenchman by the name of Paul d’Arner who authored the illustrated article, published in an October 1903 issue of Le Monde illustré, which gave birth to this issue of our incomparable blog / bulletin / thingee.

As you undoubtedly know, my erudite reading friend, Le Monde illustré was a popular and successful illustrated weekly news magazine published in Paris, France.

Mind you, the ploughing of the meadow in East Ashtabula had already been mentioned in May 1903, in the Paris daily newspaper L’Auto. Oddly enough, the Raser brothers were not mentioned by name. Indeed, some of the details in the brief text did not quite match what was published in the United States. Even so, the first and last paragraphs of that article are worth quoting, once translated of course:

Who said that peasants would always be the enemies of automobile locomotion? Here, on the contrary, they have recourse to it.

[…]

These are peasants who will certainly no longer be the enemies of drivers... if they ever were.

Now, I ask you my reading friend, were the Raser brothers the first intelligent creatures, at least on planet Earth, to use a motorised vehicle to pull a plough? Yes? No? You do not know? A good answer.

If I may be permitted to quote Lieutenant Commander Data Soong, the sapient, sentient, self-aware, unemotional and, err, anatomically functional male android of the Star Trek television and movie franchise, “the most elementary and valuable statement in science, the beginning of wisdom, is ‘I do not know.’”

While it is quite likely we may never know who was the first Earthling to use a motorised vehicle to pull a plough, we do know that some people had been looking into the possibility of using gasoline powered vehicles on a farm for quite some time.

In 1887, for example, in Illinois, John Charter, born Johannes Charter in what was then the German Confederation, supervised the installation of a gasoline engine developed by an employee of the American firm he was president of, Williams & Orton Manufacturing Company, on an otherwise unidentified vehicle, an American traction engine perhaps. The gasoline engine in question apparently drew its inspiration from a design developed several years before by the German engineer Nicolaus August Otto. The employee in question was Franz Burger, a skilled machinist also born in the German Confederation.

To answer the question forming in your little noggin, a traction engine was / is a steam-powered vehicle used to plough fields, power farm equipment and / or pull heavy loads.

In any event, Williams & Orton Manufacturing put together 6 gasoline traction engines between 1887 and 1892, by which time that firm had become Charter Gas Engine Company. All of them were put on trains going to South Dakota. Once there, they were used to pull thresher machines from bonanza farm to bonanza farm, and provide the power these huge machines needed to thresh the wheat those large exploitations were producing in ginormous quantities, and…

Yes, you are quite correct, my observant reading friend. William & Orton Manufacturing’s traction engines were never used for ploughing. Indeed, they were never intended to do that sort of thing.

What could well be the first gasoline farm tractor was completed in 1901, pretty much by hand, by the staff of another American firm, Hart-Parr Gasoline Engine Company. “Old No. 1,” as it became known, was a 4-wheel behemoth weighing 4 500 or so kilogrammes (10 000 or so pounds) which could pull a 5-disc plough. Sold to an Iowa farmer, that tractor was still at work in 1917-18, if not later.

Initially unable to find many customers, Hart-Parr Company, as the firm soon became, managed to survive. Indeed, the firm eventually thrived. And here is at least partial proof…

A typical Hart-Parr Company advertisement. Anon., “Hart-Parr Company.” The Grain Growers’ Guide, 10 August 1910, 5.

A typical Ivel Agricultural Motor, made by Ivel Agricultural Motors Limited. Anon., “Motor Farming.” The Toluca Star, 21 October 1904, no page number.

What could well be the first gasoline farm tractor to be series produced on our big blue marble was the Ivel Agricultural Motor, produced in England by Ivel Agricultural Motors Limited. The first example of that light and compact 3-wheel vehicle was completed in 1902 by a small team headed by a champion cyclist and inventor by the name of Daniel “Dan” Albone, after 5 or so years of development work.

Many of the 500 or so (?) tractors made by Ivel Agricultural Motors were exported. Would you believe some of them went as far as Australia?

And yes, several Agricultural Motors were seemingly exported to Canada. Indeed, one of those tractors might, I repeat might, have been on display at the 1906 edition of the Winnipeg Industrial Exhibition, in… Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Better yet, a small group of Manitoban and Ontario businessmen tried to launch Ivel Motor and Machinery Company Limited in Winnipeg, a firm whose ties to Ivel Agricultural Motors escape me at this time, over the summer and fall of 1906.

While it seemed that a pair of Agricultural Motors was made, or assembled, by a (small?) Winnipeg ironworks, Ivel Motor and Machinery might not have really seen the light of day, for lack of investors. This being said (typed?), a firm owned by a (former?) member of the advisory board of that firm, James Stuart Electric Company Limited of… Winnipeg, was representing the interest of Ivel Agricultural Motors at least as late as April 1910.

The English firm seemingly then took over its Canadian sale effort and kept at it until at least the end of the winter of 1912-13. If truth be told, yours truly wonders if Ivel Agricultural Motors went under around that time.

But what about gasoline farm tractors produced in Canada, you ask, my flag waving reading friend. Well, while it was / is true that several, if not many Canadian firms, well, mainly Ontario firms really, became intrigued by the possibility of producing tractors from the 1900s onward, the sad truth was those designs did not prove commercially successful, at least not during those early years of the 20th century.

In any event, many if not most of those designs included American components, important ones in some cases, like the engine.

Let us begin our brief investigation with a look at Goold, Shapley and Muir Company Limited of Brantford, Ontario, a firm, which, around 1908-09, and possibly as early as 1907, went into the gasoline tractor business. In early 1910, it set up an office in Winnipeg, in order to expand its market to western Canada. Indeed, one of the first Goold, Shapley and Muir Ideal tractors to leave the firm’s factory could have been found somewhere on the Canadian prairies no later than April 1910. Alan B. Muir could have been seen at the wheel, and seemingly more than once.

Now, I ask you, my reading friend, was that 4 wheel vehicle

- an American tractor with a Canadian sticker, or

- an American tractor assembled or fabricated under license, or

- a semi-original vehicle made primarily with American parts, or

- a thoroughly original vehicle made primarily with Canadian parts?

You do not know, now do you, my reading friend? Well, neither do I.

Formed no later than 1884 as E.L. Goold & Company, that maker of beekeeper equipment and other items gradually diversified its activities after turning into Goold, Shapley and Muir, in 1892, I think. Indeed, by 1908-09, that firm was producing gasoline engines, grain grinders, windmills, concrete mixers, root pulpers, water pumps, water tanks, lookout towers, etc.

It might also be worth noting that Sylvester Brothers Manufacturing Company of Lindsay, Ontario, designed a very innovative gasoline threshing machine in 1904-05. The firm made 3 examples of an improved model in 1907-08. Those prototypes were among the most advanced of their type anywhere on our good old Earth.

Mind you, Sylvester Brothers Manufacturing also made at least one example of an equally innovative gasoline ploughing machine in 1907. Would you believe that the plough could be detached from that (4-wheel?) vehicle, thus turning it into all-purpose farm tractor capable of pulling an 8-disc plough? Could one argue that this vehicle was the first Canadian-made gasoline tractor, you ask, my flag waiving reading friend? Well, the good folks at Goold, Shapley and Muir might have disagreed with you on that.

Sadly, it is likely we will never know how many examples of the Sylvester Brothers Manufacturing gasoline ploughing and threshing machines were produced. The fact that the latter regularly went back to Lindsay at the end of each threshing season to be adjusted and improved in time for the following season made / makes any calculation very tricky indeed.

Given the potential of the gasoline ploughing and threshing machine developed by Sylvester Brothers Manufacturing, why was it not produced in large numbers, you ask, my puzzled reading friend? Well, it all came down to time and money. The development cost of the threshing machine simply proved overwhelming for that small Canadian firm. Indeed, Sylvester Brothers Manufacturing was acquired by a farm equipment manufacturing firm, Tudhope, Anderson & Company of Orillia, Ontario, in 1911.

Now, given the promise to be brief that yours truly expressed at the beginning of this article, a promise I am beginning to regret, this might be as good a time as any to bring it to a close.

Ta ta for now.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)