One hot potato, two hot potatoes, three hot potatoes, four: Atomic Energy of Canada Limited of Chalk River, Ontario, and the early days of food irradiation in Canada

Do you remember seeing The Amazing Potato exhibition when it was presented at the National Museum of Science of Technology, in Ottawa, Ontario (1991-94), or at the Agriculture Museum, also in Ottawa (1994-2000), my reading friend? No? You saw it at the Potato Museum, in O’Leary, Prince Edward Island, after that date, between 2000 and 2012 perhaps? Wunderbar! It was a great exhibition, was it not?

Need I mention that all of these museal institutions are now, in 2021, known by other monikers? Yes, they are. Said monikers are Canadian Potato Museum, Canada Agriculture and Food Museum and Canada Science and Technology Museum, the latter pair being sister / brother institutions of the scrumptiously good Canada Aviation and Space Museum of Ottawa.

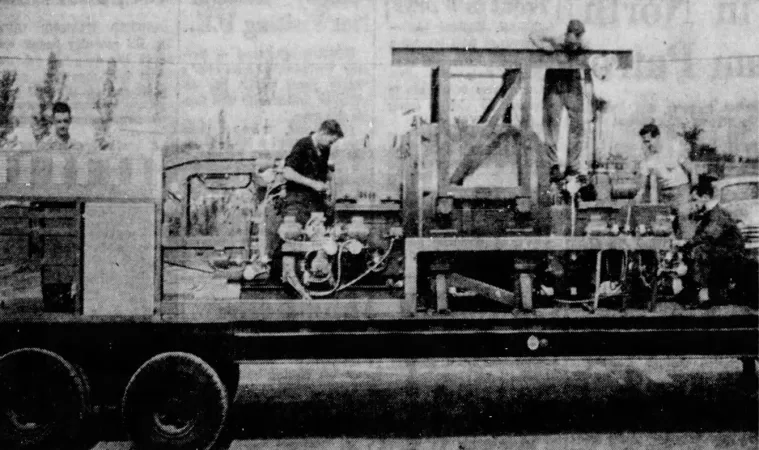

Given that this week our pontificational peroration will not be about museums, allow me to go to the root / tuber of this week’s topic by quoting the caption of the photograph you saw a few moments ago, a photograph found in the pages of the 21 October 1961 issue of Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, the main daily newspaper of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

KNOWN AS A “MOBILE COBALT-60 IRRADIATOR,” the above machine is expected to boost exports of Canadian potatoes and eliminate the need for heavy imports in late spring and early summer. The machine, which went into test operation at Ottawa Thursday [18 October], was developed by the commercial products division of Atomic Energy of Canada Limited in co-operation with the potato industry. It uses gamma rays to prevent potatoes from sprouting while in storage. Mounted on [15 or so metre] 50-foot trailer, the irradiator uses cobalt-60, the same isotope used in teletherapy treatment of cancer. The potatoes are struck only by gamma rays, and these leave no deposit which could cause contamination.

Now I ask you, my reading friend, do you think the idea of food irradiation was first mooted around that time, meaning the early 1960s? The 1940s or 1950s, you say? A good guess, but the truth is that this concept was put forward not too long after the independent and near simultaneous discovery of natural radioactivity in early 1896 by the French engineer and physicist Antoine Henri Becquerel and the British physics professor Silvanus Phillips Thompson. I kid you not. The former published the results of his experiments first, however, and got the credit.

The idea of using the newfangled rays to obliterate microorganisms which were harmful to humans or to humanity’s food supply was put forward in a German medical journal as early as 1896.

Even though patents were issued in the United Kingdom and United States as early as 1905, actual experiments seemingly began only in the 1950s. One only needs to mention the United States’ National Food Irradiation Program, launched in 1953 by the United States Army and the Atomic Energy Commission, and its experimental irradiation of plant (fruits and vegetables) and animal (dairy products, fish and meat) products. Producing long lasting field rations for soldiers fighting a war was, is and will be of crucial importance. And Homo sapiens seems to have a real knack at waging war, but I digress.

Why only in the 1950s, you ask, my reading friend? To answer that question, one has to look into the history of radiotherapy, in other words the use of various forms of radiation to treat cancer. Before the development of nuclear weapons during the Second World War, the only way to treat tumours located deep inside a human body was to use very powerful, expensive and rare X-ray machines or place a tiny amount of radium, a very powerful, expensive and rare source of radiation, inside that human body.

The development of nuclear reactors allowed researchers to produce artificial radioactive sources for medical use. A radioactive form of cobalt, a metal, known as cobalt 60, proved especially useful in that regard. Harold Elford Johns, a medical physicist at the University of Saskatchewan, in Saskatoon, played a vital role in getting the ball rolling. In 1949, he convinced the National Research Council of Canada, a renowned organisation mentioned several / many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since May 2018, to develop a Cobalt 60 radiotherapy device.

Two examples of that early machine, commonly / cheerfully christened cobalt bombs, were built, at the University of Saskatchewan and at Victoria Hospital, an institution affiliated with the University of Western Ontario, in London, Ontario.

The first person was treated in November 1951. Her cancer cured, she went on with her life, leaving this Earth around 1998. The rest, as they say, is history. Let us now return to the irradiation of food products.

The first commercial application of irradiation in the world was launched in West Germany in 1957, when Gewürzmüller Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung used a Van de Graaf electron accelerator to improve the hygienic quality of some of its spices. And yes, the firm did so in the absence of government rule or regulation. Heiliger Strohsack, Fledermausmann!

In 1958, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) became the first country on planet Earth to approve the irradiation of a food product, in this case potatoes. That treatment was to prevent the tubers from sprouting. A similar atheistic blessing was given at a later date (1959?) to the irradiation of grain to prevent insect infestations.

And yes, sprouting was and is a problem. All potatoes consumed by humans contain certain toxic compounds, but only in small and safe amounts. When potatoes sprout, however, their toxic content gradually increases. Humans who consume such potatoes may ingest excessive amounts of the toxic compounds. The lucky ones may suffer from nothing more serious than an upset stomach. The most unlucky ones may not survive the experience. Given that risk, sprouted potatoes need to be destroyed, which seriously impacts the profits of potato dealers.

It is worth noting that countries like France, Japan, Norway, Poland and the United Kingdom conducted research on food irradiation in the 1950s.

The presence of Japan in that list came as a bit of a surprise, given the fact that a pair of murderous nuclear weapons were dropped in August 1945 on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Yours truly was even more surprises to learn that such research had begun as early as 1954. Whether or not the general population was aware of said research was another matter.

And now for a word or two, or a lot more than that, on the early days of food irradiation in Canada.

Research in that field began around 1956, at Chalk River, Ontario, at the research centre of a crown corporation, Atomic Energy of Canada Limited (AECL). Researchers there initially irradiated potatoes to see if irradiation prevented that food staple from spoiling. The researchers used fuel rods extracted from the Nuclear Research Experimental reactor, or NRX, as a radiation source. Later on, they irradiated onions and apples. In the former case, experiments began in 1957, using fuel rods extracted from the NRX as a radiation source. That research was conducted in cooperation with the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Welfare.

In parallel to that work, AECL’s staff designed and built the first examples of a family of commercial research irradiators, the Gammacells, around 1956-58. These versatile devices became the main tool of the people conducting research into food irradiation in Canada at the time.

Indeed, during the early to mid-1960s, Gammacells were installed in several Canadian food research laboratories, namely

- the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, and / or Nanaimo, British Columbia.

- the Macdonald College of McGill University, in Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Québec;

- the Ontario Agricultural College, in Guelph, Ontario;

- the Université Laval, in Québec, Québec;

- the University of Alberta, in Edmonton, Alberta;

- the University of British Columbia, in Vancouver, British Columbia; and

- the University of Manitoba, in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

These institutions conducted experimental irradiation trials of plant (fruits and vegetables) and animal (dairy products, fish and meat) products.

Would you believe that more than 600 examples of the Gammacell, all versions and derivatives included, were used in research centres on planet Earth? Not all of these may have been used for food irradiation work, however.

In 1960, AECL supervised the construction of a shielded irradiation facility where large food items like sides of pork and bunches of bananas could be treated for experimental purposes.

That same year, in the fall, the Food and Drug Directorate of the Department of National Health and Welfare gave its blessing to the irradiation of potatoes. This was a North American and Western European first, as the United States Food and Drugs Administration gave its blessing to the irradiation of food products, in that case, wheat and wheat products, to prevent insect infestations, only in 1963.

The Mobile Demonstration Irradiator at the heart of this issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee was built by AECL in 1961, as a crash project. Indeed, some staff members agreed to work during their vacations so that it would be ready in time to treat freshly dug up potatoes.

Indeed, again, the Mobile Demonstration Irradiator was developed to prove to the Canadian potato industry that irradiation was a reliable, safe and simple tool able to prevent potatoes from sprouting, without changing their taste, which would allow Canadian potato dealers to lessen the cyclical nature of their business and sell good quality spuds 12 months a year.

Consisting of a fully equipped and shielded 41 metric tonnes (40 Imperial tons / 45 American tonnes) trailer which could travel by truck, train or ship, the Mobile Demonstration Irradiator went into action in October 1961, on a farm operated by Ottawa River Farms Limited, near Alfred, Ontario.

The huge device could treat approximately 1 150 kilogrammes (2 500 pounds) of spuds per hour. A Ferris wheel-like structure within the irradiator moved said spuds around its pencil-sized (!) radioactive source. Each tuber was exposed to the radiation during 4 or so minutes.

The fact that the potatoes did not come into contact with the radioactive source meant that they themselves did not become radioactive. How receptive the good folks of Canada were is unclear given that AECL had presented its baby to the world at a pratty bad time.

You see, the Mobile Demonstration Irradiator went into action a couple of weeks before the largest nuclear weapon test ever conducted on planet Earth. Yea, in late October 1961, the USSR detonated a 50 megatonne air-dropped thermonuclear weapon. Nicknamed the Tsar Bomba, or emperor of bombs, that single weapon of mass destruction was 1 250 to 1 500 times (!) more powerful than the pair of nuclear weapons dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Given the shock and awe which resulted from the Soviet nuclear test, a lot of people were understandably wary of any thingamajig which produced radiation.

Let us not forget that the early 1960s were by no means a fun time. In January 1961, a 3.8 megatonne thermonuclear weapon came very, very close to a kaboom moment after making a gentle landing near Goldsboro, North Carolina, when a United States Air Force Boeing B-52 Stratofortress bombe broke up in mid air. The East German government began to erect the infamous Berlin Wall in August 1961 and the Cuban missile crisis of October and November 1962 put the world closer to the nuclear abyss than at any time in recent history.

All right, all right, the early 1960s could also be a fun time. In October 1961, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, New York, launched a new exhibition, The Last Works of Matisse: Large Cut Gouaches. Tragically, Henri Émile Benoît Matisse’s 1953 paper-cut Le Bateau was hung upside down, a little oopsy which went unnoticed for almost 7 weeks. I kid you not.

Would you believe that, in its fully operational form, the Soviet boomcracker was to have a 100 megatonne yield? Such a weapon would have set alight flammable materials and caused third degree burns 140 kilometres (more than 85 miles) from its point of impact. The mind boggles.

And yet, the binomial / scientific name of our species is Homo sapiens, or wise man. Homo moronic seems rather more appropriate. And yes, moronic is apparently a Latin word. It means, well, moronic.

Would it be extreme to suggest to any spacefaring beings (Asgardians, Kryptonians, Valedictorians, even the Great Gonzo’s people) out there that under no circumstances should Homo sapiens be allowed to establish settlements beyond the Earth? Sorry. Back to our story.

Before yours truly forgets, it should be noted that the Soviet megabomb was not put in service. It was simply too heavy and unwieldy. One could argue that that monstrosity was designed to shock and awe any and all potential enemies of the USSR, but I digress.

All in all, during its first foray into our big chaotic world, a thoroughly experimental foray, the Mobile Demonstration Irradiator treated 355 or so metric tonnes (350 or so Imperial tons / 395 or so American tons) of potatoes in 4 provinces (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario and Prince Edward Island) between October 1961 and February 1962. A stay in the Eastern Townships of Québec may, I repeat may, have been planned but did not take place. Time constraints prevented the Mobile Demonstration Irradiator from visiting Western Canada.

All in all, again, the Mobile Demonstration Irradiator treated the potatoes of 26 individuals and firms. Six varieties of potatoes were treated.

Samples of treated potatoes were examined throughout the fall of 1961, the winter of 1961-62 and the spring of 1962 to see if all went well. From the looks of it, nothing untoward happened – and no unexpected sprouting took place. Samples of untreated potatoes sprouted before too long.

In the end, some of the potatoes treated were sold to home consumers, hospitals, hotels and restaurants in New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Ontario and Québec. To sell or not to sell, that was the question. AECL left that decision in the hands of potato warehousing or shipping firms. I will let you guess the decision of said firms.

And yes, the irradiated spuds entered the human food chain from various directions, as fresh pre-peeled boilers, potato chips, instant mashed potato flakes, frozen French fries and raw potatoes. Given the lack of legislation concerning food irradiation, the firms which marketed these products were under no obligation to point out they had been irradiated. Wow.

This being said (typed?), some (male and female?) buyers were approached to ascertain their opinion of the quality and acceptability of certain products. Whether or not some of these people were home consumers is unclear. The people consulted seemingly pointed out, however, that the irradiated fresh pre-peeled boilers and raw potatoes were in better condition than their untreated counterparts – every cell and microorganism being, err, dead of course.

Around 1962, the Mobile Demonstration Irradiator treated fish in Nova Scotia as well as apples, egg products, grain, onions and poultry in Ontario and Québec. All of that work was experimental, of course, as irradiation of these food products had not been approved by the Food and Drug Directorate of the Department of National Health and Welfare.

AECL spruced up its Mobile Demonstration Irradiator in 1963, by increasing the strength of its radioactive source and by installing both a product cooling system and an irradiator air conditioning system. By then, the device may have been known as the Mobile Cobalt 60 Irradiator.

Thus modified, the device was sent to a United States Department of Agriculture station in California that very year. It was used experimentally to irradiate a wide variety of fruits.

The first commercial application of irradiation in North America and the Western world was launched around September 1965 by Newfield Products Limited of Mont-Saint-Hilaire, Québec, using the first commercial irradiator on planet Earth, designed and built by AECL. The firm’s technical vice-president and a former AECL engineer who had worked on the Mobile Demonstration Irradiator, John Masefield, was one of Canada’s foremost pioneers in that field.

Newfield Products’ main goal was to help reduce the number of potatoes imported to Canada in July and August from the United States, mainly from Virginia and the Carolinas from the looks of it, up to 90 000 metric tonnes (about 90 000 Imperial tons / 100 000 American tons) from the looks of it, in the period between 2 crops.

And yes, imported American potatoes were apparently 2 to 4 times more expensive than local ones. By comparison, irradiated Canadian potatoes cost approximately 10 % more than their non-irradiated brethren. All in all, consumers would undoubtedly be thrilled to hear that – provided that the very act of irradiating food did not frighten them too much.

In any event, bad weather negatively impacted the quality of the Canadian potatoes irradiated by Newfield Products to prevent them from sprouting. Indeed, according to the firm, the 1965 potato crop it had to work with was the worst since the mid-1930s. Founded in 1964, Newfield Products went into receivership in November 1966.

Any interest expressed by other individuals and groups in Canada to launch similar efforts ended there and then.

In parallel to that, the governments of Canada and the United States began their first joint food irradiation research program in 1965. Said 2-year program looked at the possibility of extending the shelf life of poultry. Further experiments took place in later years.

Even though the world’s scientific community has widely endorsed the irradiation of food products, the general public was / is not always as enthusiastic. For some / many people, it was a bit of a hot potato. No pun intended. Well, all right, the pun was intended.

Concern was expressed regarding a decrease in nutritional value and an increase in toxicity, for example. The long-term safety of the people who irradiated the food products was also a source of concern. The production, transport and disposal of the radioactive isotopes used in the irradiators was yet another issue. Spokesperson of the government and nuclear industry spoke in reassuring tones, which was hardly surprising. Not everyone was convinced. This was true in the 1960s and remains true in 2021.

In 2021, food irradiation was / is very much a fact of life in Canada and the United States, but not so much in the European Union. AECL was no longer involved, however. Indeed, it seemingly put a stop to its irradiation research and development work in the late 1960s or early 1970s.

By the way, do you, my reading friend, know which of the food items you consume are exposed to radiation? To quote the website of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, the following products had been approved for irradiation by Health Canada as of 2021: flour and whole wheat flour, onions, potatoes, dehydrated seasoning preparations, whole and ground spices, and wheat. Irradiation of these products was not mandatory. A specific label appeared on packages of irradiated products, however.

Bon appétit, tout le monde.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)