“Looks Like An Animated Pipewrench,” but it flew 70 years, 2 months and 6 days ago; Or, How a Blériot Type XI made in Alberta performed an illegal 1 hour and 40 minute return flight from Calais to Dover in July 1955, part 1

Are you an aviation enthusiast, my reading friend? Yes? No? Actually, who cares. Yours truly is of the opinion that even people who do not give a rodent’s posterior about aviation might stick around long enough to read this week’s pontification in its verbose entirety. Shall we begin?

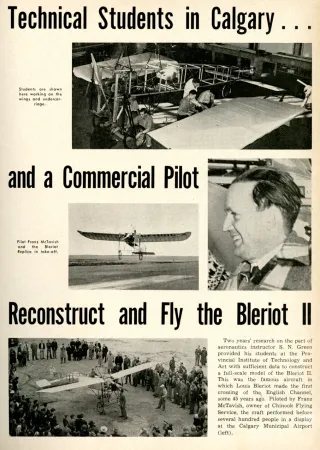

Our story began in Calgary, Alberta, at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art (PITA), at some points in the mid to late 1940s, if not earlier. The British Canadian gentleman in charge of the workshops of PITA’s aeronautics department at that time, Stanley N. “Stan” Green, was deeply interested in the early days of aviation. He came to believe that it should be possible to build a flying replica of one of the flying machines of that bygone age. He also came to believe that the students of the department would be more than willing to take part in such a project.

At some point, Green decided to supervise the construction of a Blériot Type XI.

A brief digression if I may. Green was born in England in 1905. He studied in an aeronautical school there. Green emigrated to Canada in 1924 and enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). After 5 or so years spent in Western and Northern Canada, Green joined the staff of a bush flying firm, Commercial Airways Limited of Edmonton, Alberta. He later worked for Rutledge Air Service Limited of Calgary and United Air Transport Limited of Edmonton. Green joined the staff of PITA in 1935. End of digression.

Green’s project crossed a decisive stage when he managed to locate, in the early 1950s, in a second hand book shop in Massachusetts, possibly in a municipality called Charlottetown, after 2 or so years of efforts, a crucially important source of information: a 1912 book by the American author Charles Brian Hayward, Building And Flying An Aeroplane: A Practical Handbook Covering The Design, Construction, And Operation Of Aeroplanes And Gliders.

Mind you, Leonard Anthony “Jacko” Jackson, an English aeronautical engineer, retired Royal Air Force officer and manager / curator of the Shuttleworth Collection, an English antique aircraft and automobile collection funded through the Richard Ormonde Shuttleworth Remembrance Trust, provided Green with numerous photographs and construction details of the Type XI owned by said collection.

Work on PITA’s Type XI replica began, albeit at a slow pace, in November 1952. Said pace picked up in January 1953.

By then, the project had become bicephalous. You see, Green had been joined by the founder of Chinook Flying Service Limited of Calgary. Indeed, it was David Franz McTavish who provided the engine (and propeller?), as well as much of the materials, especially the wood (mainly spruce, hickory and birch), needed to put together the Type XI.

Would you believe that a working scale model of a Type XI completed by the aeronautics department of PITA won the second prize at the 31st annual banquet if that institution, held in early February 1953?

Now, I ask you, my reading friend, why did Green choose the Type XI rather than some other type of antique aircraft? The sad truth is that we may never know.

And no, yours truly doubts that Green’s choice had anything to do with the fact that André Albert Marie Joseph Blériot, one of the two younger brothers of the French industrialist Louis Charles Joseph Blériot, yes, that Blériot, had settled in Alberta around 1902, I think, on the west bank of the Red Deer River, not too far from Munson and Drumheller, Alberta, and near the eponymous ferry which crossed said river later on. Yes, the Bleriot Ferry.

And yes, that Drumheller. The town located in the portion of the Red Deer River valley known as Dinosaur Valley. The town where one can find the world famous Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology.

Yours truly would very much like to tell you what I did near Drumheller in the summer of 1983 but modesty forbids. That, and the fear of prosecution.

Just kidding.

This being said (typed?), the Type XI was, is and will continue to be one of the most famous aircraft designed before the First World War. That fame resulted from the first crossing of the Channel by an aeroplane, a feat completed by Blériot, yes, Louis, not André, in July 1909, six or so months after the first flight of the first Type XI, in January. That fame meant that the Type XI became one of the first aeroplanes produced in large numbers.

Even though it is true that the total number of Type XIs constructed between 1909 and 1924 or so will never be known, it has been suggested that close to 3 000 examples of that aeroplane were constructed and flown across the globe.

Indeed, several of those flying machines were constructed in Canada by aviation enthusiasts. One of the first, if not the first of them was completed around October 1910 by Edward C. “Ed” Peterson of Fort William, Ontario. From the looks of it, that aeroplane proved unable to fly.

By the way, the magnificently amazing Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, has in its collection a Type XI completed in 1911, from locally-available plans and / or components, in the shops of California Aero Manufacturing and Supply Company, by John W. Hamilton, a resident of San Francisco, California, mentioned in March and June 2020 issues of our wonderful blog / bulletin / thingee. It was / is one of the first aeroplanes flown in the great state of California.

If yours truly may be permitted a deeply personal and potentially controversial thought, I find it a tad sad that this Type XI finds itself so far away from home.

Interestingly, the Type XI was not really designed by Blériot, an accident prone gentleman whose Blériot Type III to Type X were not successful powered flying machines. Nay. It was largely designed by Raymond Victor Gabriel Jules Saulnier, then chief mechanic at the Établissements Blériot Aéronautique, a sister / brother firm of the Société anonyme des Établissements L. Blériot, a well-known French manufacturer of headlamps for horse-driven carriages and horseless carriages / automobiles.

Saulnier later cofounded the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Morane-Borel-Saulnier and the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Morane-Saulnier, one of the most significant French aircraft manufacturing firms of the pre-Second World War era, and…

What is it, my reading friend? You fail to see why yours truly busts your chops with that twaddle? Well, did you know that the Borel Morane monoplane on display at the magnificently amazing Canada Aviation and Space Museum was seemingly made by the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Morane-Borel-Saulnier? That Borel Morane monoplane was / is the oldest surviving aircraft to have flown in Canada.

All but identical aeroplanes produced between 1910 and 1912 by the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Morane-Borel-Saulnier and its predecessor, the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Morane-Borel, were confusingly known as Morane, Morane Borel and Borel Morane. Some wits even called them Morel Borane.

Similar machines were also made in 1912 and later by the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Morane-Saulnier and the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Borel, but that was not all. Would you believe that a Société des aéroplanes Raymond Saulnier existed in 1909-10?

So, have I succeeded in thoroughly confusing you, my reading friend? Yes? That is good to hear (read?), because the history of aviation before the start of the First World War, in 1914, can be very confusing indeed.

All of those French aeroplane manufacturing firms were of course mentioned in October 2018 and May 2020 issues of our amaaazing blog / bulletin / thingee, as was Saulnier. Blériot, on the other hand, was so blessed several / many times since October 2018, but back to our story.

As you may well imagine, work on the Type XI under construction in Calgary came to a stop during the summer vacation period of 1953. It started afresh in the fall.

This being said (typed?), it was in June 1953 that Green and McTavish contacted the Department of Transport to have their as yet incomplete creation registered. Well aware that the Type XI did not meet modern airworthiness requirements, the department allocated it an experimental registration in January 1954.

The Blériot Type XI of the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art of Calgary, Alberta, before it received its fabric covering, on the left, and, on the right, that aircraft with some of the people who constructed it. From left to right, Walter Babiey, Bill Shearer, Keith Mathison, Stanley N. Green and Reginald Malet de Carteret. Anon., “Looks Like An Animated Pipewrench, But It Flew 44 Years Ago…” The Calgary Herald, 29 October 1953, 19.

By November 1953, the Type XI was ready to fly. With the exception of its engine and propeller and, of course, the many screws, nuts and bolts used during its construction, every component of that flying machine had come from Calgary, or Alberta.

Incidentally, the structure of the aircraft was modified somewhat to make it stronger.

And yes, the engine and propeller were of modern design.

All in all, 30 or students of the aeronautics department of PITA had worked on the Type XI.

McTavish was at the controls of the Type XI for the 1st, 2nd and 3rd flights of that machine, on 25 November 1953, at Calgary Municipal Airport, in… Calgary. An RCAF officer replaced him for the 4th and final flight of the day. Flight Lieutenant George Kelly was really thrilled.

And yes, my cautious reading friend, McTavish had performed several test runs on the ground in November before the first takeoff.

This being said (typed?), Green and McTavish agreed that their Type XI, although more powerful that the aeroplane piloted over the Channel by Blériot in July 1909, needed more oomph. A lot more oomph, in fact, and a new propeller. After all, being located at 1 080 or so metres (3 550 or so feet) above sea level, Calgary Municipal Airport was much higher than the locations where Blériot had flown back in 1909. In any event, the required changes were quickly made.

The first public flight made by David Franz McTavish aboard the Blériot Type XI built by students of the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art, Calgary Municipal Airport, Calgary, Alberta. Anon., “Pioneer Plane Flies.” The Albertan, 30 November 1953, 9.

Another view of the first public flight made by David Franz McTavish aboard the Blériot Type XI built by students of the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art, Calgary Municipal Airport, Calgary, Alberta. Anon., “1,200 See Bleriot – History Making Flight Re-Enacted In Calgary.” The Calgary Herald, 30 November 1953, 15.

Stanley N. Green, on the left, and David Franz McTavish proudly posing after first public flight of the Blériot Type XI built by students of the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art, Calgary Municipal Airport, Calgary, Alberta. Anon., “The Herald Picture Page.” The Calgary Herald, 5 December 1953, 21.

McTavish and the Type XI flew yet again on 28 November. That 20 to 25 or so minute flight was witnessed by 1 200 or so people who had made the trip to Calgary Municipal Airport.

News of the flight soon reached the offices of a French weekly aviation magazine, courtesy of a French private pilot / inventor, Hippolyte Paul Delimal, who had moved to Montréal, Québec, a few years before. Les Ailes reported with some amusement in February 1954 that Canadian newspapers had stated that the aforementioned Louis Charles Joseph Blériot had constructed and tested his first aeroplane in Alberta.

A brief check performed by yours truly showed that a Calgary daily newspaper, The Albertan, had reported that an elderly gentleman had claimed to have seen Blériot test a powered aeroplane and, before that, if I read correctly, a glider, near Munson. Those flights allegedly took place several years before the First World War, at a farm where Blériot and his two brothers lived.

That elderly gentleman was mistaken.

Human memory is indeed a faculty that forgets, or even a faculty which can sometimes remember events which never took place.

Mind you, the good people at Les Ailes wondered why Green had not contacted the Musée des arts et métiers, the oldest science and technology museum on planet Earth and a component of the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers, a renowned French higher learning institution specialising in science and technology education and in the dissemination of such knowledge. You see, the collections of that museal institution included the very Type XI piloted across the Channel by Blériot.

The museum is well worth the visit, trust me, but back to our story.

You have a question, my reading friend? Were early aeroplanes tricky, if not downright dangerous to fly? Well, the sad truth was that many of them were both tricky and dangerous to fly, which explains why more than 400 people died in powered aeroplane accidents before the onset of the First World War, in 1914.

Let us not forget that the people who designed the first aeroplanes had no previous experience in that field. Worse still, the people who test flew those aeroplanes had no previous experience either. As a result, the first and last flights of a particular machine were all too often one and the same.

Indeed, the Type XI was far from being easy or pleasant to fly. Yours truly would almost dare call it a flying clothes iron.

Given that, you will not be surprised to learn that the Albertan Type XI suffered a fair amount of damage in the spring of 1955, at Calgary Municipal Airport. Its pilot was not injured.

The story of the Type XI took an unexpected turn in late December 1954, or early January 1955, as a result of a devastating fire which destroyed, in early December, a hangar at Calgary Municipal Airport as well as the 25 or so aircraft it contained.

One of those aircraft was a de Havilland Tiger Moth owned by two Edmonton building contractors / property developers in their mid-20s and early-30s, French from France Canadian Jean Henri Brion Chopin de La Bruyère and Scottish Canadian Alastair Auld « Sandy » Mactaggart.

Incidentally, you might be pleased to learn (read?) that de La Bruyère was a grandson of the French aviation pioneer Louis Charles Bréguet, a contemporary the aforementioned aviation pioneer Louis Charles Joseph Blériot.

De La Bruyère and Mactaggart had met at Harvard Business School, the graduate business school of Harvard University of Boston, Massachusetts, in 1950 or 1951. That meeting allegedly took place in the showers of a dormitory. You see, Mactaggart was having a shower while wearing a kilt. I kid you not.

In any event, de La Bruyère and Mactaggart became fast friend and eventually decided to go into business together. Both men wondered where they might set up shop, Venezuela or Alberta. The latter came out on top. Maclab Construction Company Limited came into being in Edmonton in 1953.

And yes, the word Maclab was a portmanteau which blended the family names of Mactaggart, who was the firm’s president, and de La Bruyère, who was its director.

Both Mactaggart and de La Bruyère being pilots, they soon bought themselves a Tiger Moth light / private plane and had some fun.

The December 1954 conflagration brought that fun to a fiery stop.

Need yours truly remind you that the astonishing Canada Aviation and Space Museum has a Tiger Moth, well, a Menasco Moth actually, in its world class collection? I thought so.

In January 1955, as Mactaggart and de La Bruyère ruefully scanned the charred remains of their aircraft, wondering what to do next, their path crossed that of Lieutenant Commander Robert Frank Lavack, the commanding officer of VC 924, the Calgary-based reserve squadron of the Royal Canadian Naval Air Branch of the Royal Canadian Navy. As they collectively commiserated the loss of their aircraft, the aforementioned Tiger Moth on the one hand and the squadron’s trio of North American Harvard training aircraft on the other, Lavack mentioned the Type XI in passing.

And yes, you are quite right, my reading friend, the world class collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum does indeed include a pair of Harvards.

Another version of the story had the rueful Mactaggart and de La Bruyère crossing the path of Green and McTavish. Mind you, it is also possible that this meeting was a consequence of the meeting with Lavack.

In any event, Mactaggart and de La Bruyère were of the opinion that their next aircraft should be something a tad unusual.

Someone, and no one quite knows who, suggested that a recreation of the cross-Channel flight made by Blériot, yes, Louis Charles Joseph Blériot, in July 1909, might be a good idea. Better yet, Mactaggart and de La Bruyère decided to make that flight on 25 July 1955, 46 years to the day after the historic flight made by Blériot.

Following up in the virtual footsteps of that decision, de La Bruyère and Mactaggart acquired the Type XI in mid-May 1955.

The dynamic duo’s cross-Channel flight plan, as it existed at that time, would see the aforementioned Green and the Type XI leave Calgary by train, presumably in late June. Their destination would be the port of Montréal, where the precious machine and its minder would be put on a ship.

And yes, Green was to travel free of charge. He might have planned even then to spent some time in England.

Once in France, Green and the Type XI would make their way to Calais, by train or truck, yours truly cannot say. In any event, again, Green was to reassemble the aircraft in the field Blériot had lifted off from in July 1909.

De La Bruyère, on the other hand, was to board an airliner bound for France in mid-July. He would be at the controls of the Type XI for the flight across the Channel.

How had the choice of pilot been made, you ask, my reading friend who wants to know? Well, de La Bruyère and Mactaggart had flipped a coin.

De La Bruyère would try to have a helicopter and a motor boat nearby throughout the flight, in case something went wrong. Quipped the young man, “I’ve no desire to offer competition for any Channel swimmers who may be about…”

After said flight, Green, de La Bruyère and the Type XI would return to Alberta. The aircraft would presumably be put on display in a few places along the way, including, possibly, at the Canadian National Exhibition, in Toronto, Ontario, in August.

While yours truly does not doubt that, like John “Hannibal” Smith, the charismatic leader of the A Team at the heart of the eponymous American action / adventure television series broadcasted between 1983 and 1987, Mactaggart and de La Bruyère loved it when a plan came together, the sad truth was that a comment made by the Canadian philosopher / professor Herbert Marshall McLuhan might be quite appropriate here: “To see a man slip on a banana skin is to see a rationally structured system suddenly translated into a whirling machine.”

And yes, that was a loooong sentence. An em dash or two would have been useful. (Hello, EP!)

And no, things did not go according to plan.

To find out how, however, you will have to come back in a few days. Adiós amigo!

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)