“Halloa! There’s something strange going on up there;” Or, How an aerolite the size of a house narrowly missed a passenger-cargo ship in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean in August 1907, part 1

Top of the morning to you, my reading friend.

At the risk of repeating myself, yours truly readily admits that I have had, have and will presumably continue to have a strong affinity toward the unusual, the strange, the odd looking, etc. Juggling that fact while balancing a wish to commemorate an anniversary, namely mine, sort of, I choose to temporarily put aside the anniversarial approach of our awesome blog / bulletin / thingee to offer myself a wee present.

Let us begin our journey down the yellow brick road of memory lane.

Speaking (typing?) of memory, my reading friend, you will undoubtedly remember that I very briefly mentioned today’s topic in a July 2023 issue of our celestial blog / bulletin / thingee, but I digress.

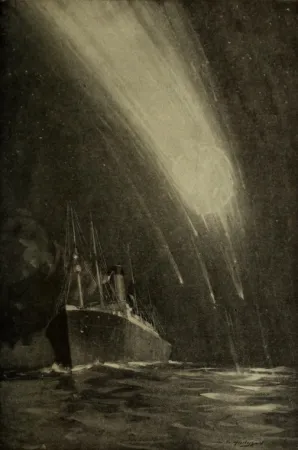

The British passenger-cargo ship SS Cambrian. D.H. Vittery, “More Queer Fixes, XII – A Meeting with a Meteor.” The Wide World Magazine, May 1908, 4.

One could argue that the story at the very heart of this issue of our you know what began in December 1896 when the passenger-cargo ship SS Cambrian was completed, in England, for an English shipping line, Wilsons & Furness-Leyland Line Limited, which happened to be a subsidiary of an American trust, International Mercantile Marine Company.

The ship immediately began to cross the Atlantic Ocean on a regular basis, between Europe (mainly England) and America (mainly the United States).

Among other things, SS Cambrian carried to England heads of cattle as well as Canadian work horses of various types. It also carried many North American cattlemen returning home.

Some of the items carried over the years in the vast holds of the ship included whisky, walnuts, sumac, rice, rhum, various ores, olive oil, mica, jute, herring, hemp, straw hats, gin, patent drugs, cocoa, chalk, burlap, beer, beans, tartaric acid and carbolic acid. That list, incidentally, came from a single trip to Boston, Massachusetts, completed in March 1907.

Mind you, the ship carried at least 5 stowaways over the years, including, in December 1915, a pair of young Russian tailors of Polish origin who had taken the place of a pair of American cattlemen returning home. Tried in England after being caught by American immigration people, the 2 men were accused of trying to avoid military service. They spent 4 months in jail before being deported.

It might be worth noting that, in January 1905, the crew of SS Cambrian delivered 8 000 or so bales of wool to American buyers anxiously waiting their arrival in Boston. That shipment was said to be the largest delivered until then to that city by a single ship.

In July, the ship narrowly escaped destruction by fire during a trip between London, England, and Boston.

And yes, the crews of SS Cambrian faced a great many storms over the years. The February-March 1907 crossing was a particular stressful one, for example.

Another stressful crossing began on 7 August 1907, in the port of London. And yes, that crossing is the one at the heart of this article.

At the time, the captain of SS Cambrian was Ernest Coulman Hiscoe. His first officer was Thomas Hughes. Hiscoe’s second officer and the author of the article which led to the article you are reading, my reading friend, was Daniel H. Vittery, quite probably Daniel Herbert Vittery. The three of them were British subjects, I think.

The first 10 or so days of the August 1907 journey were uneventful. SS Cambrian was carrying various items, as well as some cattle – and the cattlemen needed to take care of them. Seven of those cattlemen were in fact American students eager to spend a few days in Europe.

And yes, those days were few indeed. Only 6 in fact, then the young Americans had to board SS Cambrian for the journey home.

Then came 16 August.

The second officer of the British passenger-cargo ship SS Cambrian and author of the article which led to the article you are reading, Daniel H. Vittery, quite probably Daniel Herbert Vittery. D.H. Vittery, “More Queer Fixes, XII – A Meeting with a Meteor.” The Wide World Magazine, May 1908, 3.

The night of 16 August, as SS Cambrian sailed west, 560 or so kilometres (350 or so miles) south of Newfoundland, Vittery noted how fine the weather was. Only a slight swell moved the waters of the Atlantic Ocean. The sky was cloudless and the stars were plainly visible, as was a comet, to the north.

And yes, that celestial body was presumably comet C/1907 L2 (Daniel), discovered in June 1907 by Zaccheus Daniel, a graduate student in astronomy at Princeton University, a renowned American institution of high learning. That comet was the brightest seen that year, incidentally.

Thomas Hughes, the first officer of the British passenger-cargo ship SS Cambrian. D.H. Vittery, “More Queer Fixes, XII – A Meeting with a Meteor.” The Wide World Magazine, May 1908, 4.

At some point, Hughes came to the bridge to take his watch and relieve Vittery. The two men chatted for a few minutes. As the latter prepared to leave to get some shuteye, he and Hughes noticed some meteors streaking over the starboard / right side of SS Cambrian, from the northeast to the southwest. Some of those meteors had bright tails whose light was sufficient to create shadows on the main deck of the ship.

“Halloa! There’s something strange going on up there,” stated Hughes, a quote extracted from Vittery’s article, as are all other quotes, but back to our story.

He and Vittery watched that impressive display until it petered out, after a couple of minutes or so.

As the two talked about what they had seen, a second meteor shower began, which was even more impressive that the first. As more and more meteors flashed above SS Cambrian, Vittery suggested that Captain Hiscoe be roused from his slumber so that he too could enjoy the show. Given how much time the latter had spent on the bridge, however, Vittery soon agreed that the captain should be allowed to rest.

Hughes had just wondered aloud what would happen next when,

from the sky to the north-east, there flared up something that looked like a rocket, save that it was much larger, and the train of fire that followed its glowing head trailed away behind like a horse’s tail, while fragments of fiery matter fell away from it like a shower of spray, and now and then a larger piece dropped off into the sea.

Before long, the meteor was high above SS Cambrian, casting as bright a light over the ship as the dawn of a new day. It seemed to be heading directly toward the ship.

Vittery and Hughes were now feeling more than a tiny bit uneasy. If that fiery mass hit SS Cambrian, the ship and its crew would vanish without a trace.

The meteor seemed to pause for a moment, at the high point of its trajectory. Then it began to fall toward the Atlantic Ocean. Vittery was convinced it was heading directly for SS Cambrian. As the meteor grew nearer, a blinding bluish-white light flooded the heavens. A faint sound could be heard. As it grew louder, it turned into a hissing roar.

The fiery mass was falling so fast that any attempt to alter course would be pointless. Vittery and Hughes could only stand on the bridge, their hands on the railing, transfixed by that hellish vision, and hope for the best.

The meteor’s light became so bright that neither man could directly look at it. Its roar was deafening.

“Good heavens! It’s going to drop on the fore-deck!,” shouted Hughes, barely audible over the din.

Thankfully, he was mistaken. As small fragments of the meteor hit the waters of the Atlantic Ocean around SS Cambrian, the main body of said meteor, a fiery mass as big as a house, hit 50 or so metres (165 or so feet) off the port / left side of the ship, giving it a good shake. A large wave then swept across the after-deck.

SS Cambrian and its crew emerged from their ordeal unscathed.

The sky, cloudless and full of stars only a few minutes before, seemed overcast. It soon cleared, however.

To quote Vittery,

The remainder of our passage to port was uneventful, but we who saw that meteor are firmly convinced that such appalling visitations must be reckoned with in considering the fate of well-found, well-manned ships which mysteriously disappear at sea.

A comment if I may. Had the meteor in question been as big as a house, its impact so close to SS Cambrian would probably have sent to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. That extraterrestrial visitor was therefore a lot smaller.

In any event, SS Cambrian arrived in Boston on 20 August. The first newspapers articles detailing its close encounter with a wayward celestial body came out the following day, at least in the United States.

Oddly enough, an article which mentioned the arrival in Boston of the aforementioned American students did not mention the meteor. They might perhaps have slept through the entire thing, blissfully unaware that, but for 50 or so metres (165 or so feet), their lives would have ended in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

Incidentally, Vittery’s text about his close encounter of the celestial type was published in the May 1908 issue of The Wide World Magazine, an English illustrated monthly magazine whose motto was “Truth is stranger than fiction.”

For the officers and crew of SS Cambrian, said encounter was but one episode in their busy and adventurous careers.

On 15 December 1907, for example, the propeller shaft of the ship broke off as it sailed between London and Boston. The crew of SS William Cliff, a cargo operated by Frederick Leyland & Company Limited on its way to England, came to the rescue the following day.

As the weather worsened, on 18 December, the tow line snapped. As the weather improved, another tow line was secured. That second line snapped in 20 December. Worse still, the crew of SS William Cliff lost sight of SS Cambrian. A new line was secured on 22 December. That third line snapped on 28 December, near the southern coast of Ireland. A new line was secured that same day. SS Cambrian docked in Crookhaven Harbour, Ireland, several hours later and the crew of SS William Cliff was able to continue on its way. It arrived in Liverpool, England, 10 days late, on 30 December.

Would you believe that, in March 1902, the crew of SS William Cliff had come to the rescue of RMS Etruria, an ocean liner operated by Cunard Steamship Company Limited, a famous firm mentioned in a September 2022 issue of our oceanic blog / bulletin / thingee? And yes, that ship had lost its propeller shaft.

Repairs seemingly kept SS Cambrian out of commission until mid to late January 1908.

You may wish to note that what follows was tragic.

On 2 February, more than 325 kilometres (more than 200 miles) off the coast of Nova Scotia, it came across a cargo ship operated by a shipping firm hailing from England, I think, Phoenix Line. SS St. Cuthbert was on fire. A passenger-cargo ship operated by a famous British shipping firm, White Star Line Company, was already on the scene but the strong wind and large waves had made any rescue attempt impossible.

A team from SS Cymric was finally able to make three harrowing trips to the burning ship, rescuing 40 or so men, many of them seriously burned. SS St. Cuthbert was lost at sea, as were 15 or so sailors.

Wilsons & Furness-Leyland Line sold SS Cambrian to Frederick Leyland & Company in 1914.

In June 1917, I think, as the First World War raged, that passenger-cargo ship became an armed convoy escort ship, HMS Bostonian. It was torpedoed in the Channel in 10 October, by a German submarine, during a trip between England and the United States. Four members of the crew lost their lives.

It is worth noting that Vittery eventually moved to Canada, presumably with his spouse and children. He died in Burnaby, British Columbia, in July 1964, at the age of 83.

Did the tale of SS Cambrian’s close encounter with meteor leave a slight taste of doubt in your mouth, my reading friend? Yours truly knows that feeling. This being said (typed?), you may wish to doubt that doubt. Let me explain.

But first, let us go over some technical terms. A meteoroid is a rocky or metallic object that travels through space. If a meteoroid of a certain size enters the atmosphere of the Earth, friction with molecules of gas present up there heat it up, thus creating a beautiful / frightening streak of light in the sky, in other words a meteor. If a meteoroid is large enough, it will punch its way through said atmosphere and hit the Earth, either in one piece or not. The part(s) of the meteoroid that hit the Earth are / is called a meteorite. Now back to our story.

Let us begin with the loss which befell a farmer who lived near Jackson, Missouri. On the bright and sunny morning of 18 June 1907, Elam Masterson was on his way to nearby Cape Girardeau, Missouri, with a wagon full of dry hay when he heard a loud noise. Turning to see what was going on, that non smoking farmer was shocked to see that his hay was on fire. Masterson immediately jumped from the wagon, badly hurting a foot. Battling the pain, he unhitched his horses from the wagon and moved a short distance away. Masterson could do nothing as his hay and wagon were destroyed. With spontaneous combustion or a match out of the picture, some thought that a meteorite was the culprit.

It should be noted that news reports published several days later outside Missouri stated that a meteorite the size of a baseball was indeed the culprit. Mind you, some of those news reports stated that the meteorite incident had taken place in Michigan. To quote that snippet published many times as the days went by, “How do we know but that some fancy pitcher on Mars tossed over the plate one so hot that it got away and took a shoot out through space?”

Did that tale of the burning hay wagon leave a slight taste of doubt in your mouth, my reading friend? Yours truly still knows that feeling. This being said (typed?), you may wish to doubt that doubt. Let me explain. Again.

Early in the morning of 18 June 1907, yes, yes, 18 June 1907, a tremendous shriek, a blinding flash of light and a deafening report woke up many people in the township of Bolton, Kansas. One of those people was a farmer by the name of Roy Farrell Greene. Soon after daylight, Greene went out to uncover what taken place. He soon realised that his neighbours were also trying to ascertain what had occurred. In any event, Greene soon came upon a large and partially buried rock 300 or so metres (1 000 or so feet) south of his house. Greene broke off some pieces and took them to Topeka, Kansas, where the people he showed them to stated they had never seen rocks like those.

And no, yours truly cannot say if that rock was a real meteorite.

Some people wondered, however, if the rock found by Greene had come from the comet which, some people thought, was threatening to bring about the end of the world, and…

Yes, yes, the end of the world.

You see, back in February 1907, or perhaps a tad earlier, an officer of the kaiserlichen und königlichen Kriegsmarine, in other words the Austro-Hungarian navy, based at the Austro-Hungarian naval astronomical observatory, the Sternwarte der kaiserlichen und königlichen Kriegsmarine in Pola, claimed he had discovered a comet with a greenish glow.

The tail of said comet, Lieutenant Egon Marchetti believed, would cross the path of the Mediterranean region of Earth in mid-March. The consequences of such a contact might be an apocalyptic fire. Worse still, according to some, the comet itself might smash into our big blue marble.

Somewhat surprisingly, some, if not many Homo sapiens did not take too kindly to either possibility.

Given our current presence on planet Earth, one could only conclude that Marchetti was mistaken.

And yes, greenish comets do exist. Their unusual coloration might result from a photochemical reaction between sunlight and molecules like diatomic carbon exuded by those celestial bodies when they get close to the Sun, but back to our meteors.

At some point during the week of 7 July 1907, hundreds of people enjoying the evening on the boardwalk of Wildwood, New Jersey, saw a brilliant meteor fall into the sea, or so they thought, 15 or so kilometres (10 or so miles) off shore. A rock deemed to be a meteorite was found in a field not too long after. Weighing a few kilogrammes (several pounds), that rock had obviously been subjected to intense heat.

And no, yours truly cannot say if that rock was a real meteorite.

During the evening of 21 July, one of the brightest meteors seen until then in that region raced across the sky above Norfolk, Nebraska, moving quickly from the southeast to the northwest. It broke up in numerous fragments. The meteor’s long tail illuminated the heavens like a searchlight.

During the dark and stormy night of 26 to 27 July 1907, I think, a farmer from Centerville, Ohio, near Dayton, saw a dazzling light, heard a whizzing sound and felt the earth shake beneath his feet. In the morning, James Cook came upon a large hole in the ground, 90 or centimetres (3 or so feet) in diameter and 4 or so metres (13 or so feet) deep. He quickly contacted his neighbours. Using a pole, the small group came to the conclusion that an iron meteorite weighing perhaps several metric tonnes (Imperial tons / American tons) had buried itself on their doorstep. Cook planned to have the heavenly visitor extracted from its earthly prison so that it could be used for scientific and exhibition purposes.

Within a few days, however, the men who were digging toward the iron mass came upon a stone wall. They quickly realised that the hole dug by the meteorite was in fact what was left of a well which had been covered for a number of years. Undoubtedly disappointed, the diggers went home, as did the final groups of gawkers who had flocked to the site.

During the night of 31 July, a meteor with a trail of sparks appeared in the western sky over Yoho National Park, in British Columbia. It disappeared in a blinding greenish flash in the vicinity of Mount McArthur.

And yes, yours truly realises that those events had few if any connections with the event which might, I repeat might, have been connected with the frightening experience of the deck crew of SS Cambrian, in the other words the 1907 appearance of the Perseids, a very well known and consistently spectacular meteor shower associated with the comet 109P/Swift–Tuttle which reached, and still reaches, its peak between 9 and 14 August of each year. I just thought you might find them intriguing. And yes, my punctilious reading friend, that was a looong sentence. (Hello, EP!)

The comet in question was independently “discovered,” in July 1862, by two self-taught American astronomers, Lewis A. Swift and Horace Parnell Tuttle. Yes, yes, discovered in quotation marks. You see, the comet in question had been observed by Chinese astronomers in 188 and 69 before the common era.

Incidentally, the 1907 Perseids seemingly reached their peak on 10 August.

And no, the Perseids and the comet did not / do not travel together. The former pay us a visit every year. The latter, on the other hand, only comes by every 133 or so years. Given that its most recent flyby was in 1992, it is unlikely that you or I will be around to see it again, in 2038, err, 2126. (Hello, EP!)

Incidentally, the orbit of comet 109P/Swift–Tuttle is quite stable. A collision is not to be feared, which is good. You see, with a diameter or 26 or so kilometres (16 or so miles), that comet would release more than 25 times the energy released by the asteroid which created the Chicxulub impact crater 66 or so million years ago. Yes, that 180 or so kilometre (110 or so miles) impact crater. The one which wiped out 3 out of every 4 plant and animal species on Earth.

And now for celestial events on this Earth which might have been associated with the 1907 Perseids. Well, now as in a few days actually. Sorry.

By the way, did yours truly mention that a meteor made its way through the protective atmosphere of our planet on 30 June 1908? The object in question exploded in mid air. The blast flattened / knocked over gazillions of trees over a sparsely inhabited 2 150 or so square kilometres (830 or so square miles) area of Eastern Siberia, Russian Empire. Several / many people died in what is commonly referred to as the Tunguska event / incident.

Pleasant dreams.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)