“Two petroleum steak tartare for table 13, and move yourselves, god dang it!:” The great adventure of a manna which briefly had the wind in its sails, single-cell proteins grown on petroleum derivatives, Part 1

Do you like good chow, my reading friend? If your answer was a resounding yes, let me advise you that the subject of this article may not activate your digestive juices.

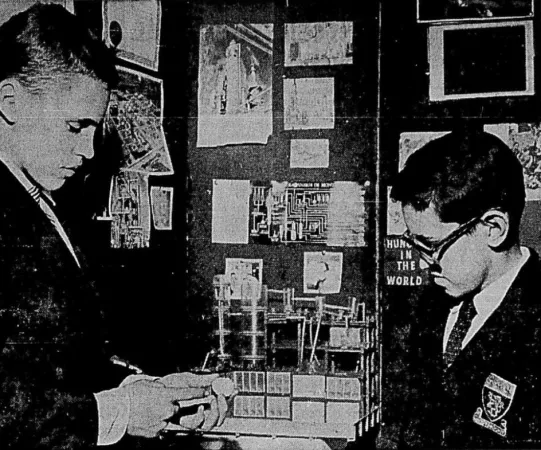

Said subject found its origin in an article published 60 years ago in the important daily newspaper La Presse of Montréal, Québec. Journalist Roland Prévost described therein the remarkable project that two young Quebecers, two brothers in fact, Roger Mallette, 14 years old, and André Mallette, 11 years old, carried out for the 4th Montreal Science Fair which was held on 4 and 5 April 1964 at the Chalet de la Montagne, in Montréal of course.

By the way, said science fair was supported by the Commission des écoles catholiques de Montréal, the Protestant School Board of Greater Montreal, several professional scientific organizations and the Québec Ministère de la Jeunesse.

Yes, yes, the Ministère de la Jeunesse. You see, there was no Ministère de l’Éducation in Québec in April 1964. I kid you not.

Before July 1960, education in Québec was the responsibility of the Département de l’Instruction publique, a simple department of the Secrétariat provincial, a sort of catch-all ministry which oversaw public education, health, etc.

In fact, the Département de l’Instruction publique was above all a management body. It was the roman catholic church which controlled schools, colleges and universities in the catholic sector.

The real decisions concerning the education of the vast majority of the population of Québec, the catholic population, were in fact taken during the meetings of the Comité catholique of the Conseil de l’instruction publique, an organisation whose members, obviously not elected, were the very conservative roman catholic bishops of Québec and an equal number of lay people who were not known for their liberalism or open-mindedness either.

In July 1960, the Département de l’Instruction publique was transferred to the Ministère de la Jeunesse. It became the Ministère de l’Éducation in May 1964. I know, the mind boggles, but back to our two young people.

The project of the Mallette brothers, two students from the Académie Saint-Léon, a private school located in Westmount, Québec, not far from Montréal, was, in translation, a “miniature factory capable of manufacturing food proteins by cultivating microorganisms on petroleum, following a process developed in France.” Pretty impressive, was it not?

More than 10 000 people went to the Chalet de la Montagne on 4 April (evening) and 5 April (morning and afternoon) to admire more than 150 (around 180?) projects in astronomy, biology (descriptive and experimental), chemistry, engineering, geology, mathematics and physics created by around 300 young francophones and anglophones from many secondary schools and classical colleges, and even perhaps a few primary schools, from the Montréal region.

Incidentally, the person who officially opened the Montreal Science Fair was none other than the director of the Institut de médecine et de chirurgie expérimentale at the Université de Montréal, in… Montréal, and a world pioneer in stress studies, the Hungarian-Canadian endocrinologist János Hugo Bruno “Hans” Selye, born Selye János.

I wish I could tell you that the Mallette brothers won an award but unfortunately that was not the case. It sure was the case that a subject which interested a journalist did not necessarily arouse the enthusiasm of the members of a jury.

The big winner of the Montreal Science Fair of 1964 studied at the Séminaire de Sainte-Thérèse, today’s Collège Lionel-Groulx, in… Sainte-Thérèse, Québec. His name was Jean Vallières.

An amateur astronomer since 1959, that young man of 20 years, I think, was awarded the Médaille du lieutenant-gouverneur, youth category, in bronze, and a scholarship of $ 500, a sum which corresponds to approximately $ 4 850 in 2024 currency. Said scholarship took him to England. Vallières subsequently completed studies in physics at the Université de Montréal.

That founding member and first president, in 1975, of the Association des groupes d’astronomes amateurs du Québec (AGAAQ), today’s Fédération des astronomes amateurs du Québec, was the author of a very popular work, Devenez astronome amateur, published in 1980 – and republished in 1984 and 1987.

That physics professor at what was then the Collège d’enseignement général et professionnel (CEGEP) Lionel-Groulx, in Sainte-Thérèse, had published Initiation à l’astronomie in 1978.

In April, May and June 1977, Vallières appeared to collaborate on the television show À la belle étoile, produced with the support of the AGAAQ and the Fédération québécoise du loisir scientifique (FQLS). That 13-episode series was broadcasted in Québec by a cable television firm active in the province, National Cablevision Limited of Vancouver, British Columbia.

Over the years, Vallières was honoured more than once by his peers. In 1972, for example, he was the first recipient of the Étoile d’argent trophy, an award awarded annually by the Centre d’astronomie de Montréal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada to a francophone Quebecer (Canadian?) who had distinguished herself or himself through her or his writings or achievements.

By the way, Vallières was then editor of L’Annuaire astronomique de l’amateur, a very useful, if not essential, annual reference work, which included all astronomical phenomena worthy of mention. He carried out that work between 1965 and 1975.

And yes, the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada was mentioned many times in our admirable blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since December 2018.

In 1976, Vallières received the Prix du loisir scientifique awarded annually by the FQLS to a person who had distinguished herself or himself through her or his research and / or animation work.

In 1990, he received the AGAAQ Méritas trophy awarded annually to a member of a club affiliated with it, to highlight her or his great contribution to the progress of astronomy in Québec.

Retired in 1999, I think, Vallières launched the Kepler II and Coelix educational astronomical software packages in May 2000 and March 2003, but I digress. In a big way.

You are undoubtedly wondering how the Mallette brothers came to decide to submit their miniature factory project. The fact was that, according to La Presse of course, it was after reading an article published a few months earlier in that important daily newspaper that the idea came to them.

Personally, yours truly was a tad skeptical. You see, the article in question appeared in January 1964. I ask you, do you believe that our young friends would have had the time to send a letter to Europe, wait for a response, digest said response, build their miniature factory and debug said factory in just 12 weeks during which they were in class Monday to Friday?

Yours truly had to admit, however, that only the important daily Le Soleil of Québec, Québec, seemed to publish a text on the culinary potential of petroleum during the fall of 1963, around mid-October to be precise. As implausible as it might seem, the Mallette brothers appeared to have done everything they had to, from sending the letter to debugging their factory, in just 12 weeks. Kudos!

By the way, the January 1964 article in La Presse was entitled, in translation “The petroleum which feeds: A possible solution to undernourishment.”

According to the anonymous author of that article, words translated here, recent research had demonstrated that certain types of yeast grew on certain petroleum by-products.

The new and very important perspectives opened up by this research raise two questions: firstly, could we obtain ‘harvests’ of microorganisms derived from petroleum, in order to produce foods which would compensate for the shortage of protein provided by meat from which so many men [sic – so many women and children too] on Earth suffer? secondly, these micro-organisms have the advantage of feeding exclusively on the elements which, in petroleum, are the least valuable: this being the case, could we not take advantage of those properties to increase the value of the petroleum?

And yes, moolah seemed to matter at least as much to the firm carrying out this research as the survival of hundreds of millions of human beings. Sorry, sorry.

Speaking (typing?) of moolah, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization information located by the journalist suggested that synthetic proteins could be 13 to 15 times cheaper than natural proteins found in meat, but back to the firm which carried out the work in question.

That firm was the Société française des pétroles BP, the French subsidiary of the British petroleum giant British Petroleum Company Limited.

The person leading the work on synthetic proteins was its research director, the French mechanical engineer / chemist Alfred Champagnat. Said work began in 1957.

It was perhaps linked at least in part to the fact that the diesel fuel / diesel oil / gas-oil / gasoil produced at that time by the Société française des pétroles BP’s Lavéra refinery, in Martigues, France, not far from Marseille, from Libyan petroleum, contained a tad too much paraffin. That paraffin actually made that diesel fuel overly viscous in cold weather. Any process capable of reducing the amount of paraffin present in that product would be welcome. If said process was able to produce proteins with good commercial value, that would obviously have been even better.

As you might expect, Champagnat’s work had moved somewhat beyond laboratory research by 1964.

Anxious to launch an important research program, Champagnat might, I repeat might, have used a slightly heterodox approach. He presented 2 hams to British Petroleum big wings, the first from a grain-fed pig and the second from a petroleum protein-fed pig. Said big wigs were incapable of distinguishing between them. Champagnat got a green light.

Another version of the story was that a very emotional presentation given by Champagnat in broken English at a British Petroleum research conference in France, a presentation which included images of undernourished people, led to a standing ovation – something unheard of at such a conference.

Incidentally, Champagnat became the first director of a new research organisation formed in 1964 or 1965 by British Petroleum, the Société international de recherche BP.

In any event, the Société française des pétroles BP had, around 1963, a pilot plant on the site of the Lavéra refinery. That pilot plant could produce 1 000 or so kilogrammes (2 200 or so pounds) of protein concentrates per day from diesel fuel.

Very interested in Champagnat’s work, the Mallette brothers wrote to him to obtain further information. Were they already planning to create a presentation for the 4th Montreal Science Fair, you ask, my reading friend? If only I knew.

In any event, Champagnat was only too pleased to send information on his production process and samples of protein concentrates to the young Quebecers.

Once that documentation had been received and well assimilated, the Mallette brothers used an unidentified construction set as well as several (glass?) jars and several plastic tubes.

In his April 1964 article, the aforementioned Prévost pointed out that, as you might imagine, the miniature factory did not work the first time. Several modifications were necessary. This being said (typed?), it ended up producing a white powder similar to that produced by Champagnat in France. Its quality was probably not as good as that of the protein concentrates produced by the pilot plant, of course, but the fact that this powder existed was pretty impressive nonetheless.

Just like their French counterparts, the small concentrate biscuits produced by the Mallette brothers were very nutritious. For example, they contain a lot of lysine, an amino acid essential for human and animal health, which made them an excellent supplement for foods which contained very little, wheat and corn for example.

Prévost concluded his April 1964 article with a few strong sentences, translated here:

It can never be said too often: the world is hungry. Two thirds [sic] of humanity suffer from undernourishment. The current demographic surge makes this problem more acute every day, but there is no reason why we cannot escape it. ‘The only practical limit to food production is the amount of capital, labor, and research we are willing to devote to it.’ That saying from Lord John Boyd Orr, Mr. Alfred Champagnat highlighted it in one of his articles.

Prévost was under no illusion, however, words translated here: “The cultivation of microorganisms on crude oil is not ‘the’ solution to world hunger.”

Before I forget it, Baron Boyd-Orr of Brechin Mearns, born John Boyd Orr, a Scottish professor / politician / physician / nutritional physiologist / farmer / businessman / biologist, spoke and / or wrote the words quoted above in 1953.

A brief reminder if I may. A third, not two thirds, of the Earth’s population, more than a billion people, suffered from undernourishment in 1964. In 2024, 700 to 800 million people suffered from the same problem, or about 1 person in 11. While it is true that the situation had improved over the years, that improvement is little consolation for the people who are hungry at this moment.

By the way, the world’s 195 countries spent about US $ 2 200 000 000 000 on defence in 2023, or about US $ 275 for every living or surviving human being on Earth.

Meanwhile, 1 billion people around the world lived or survived on less than US $ 1 a day, the threshold defined by the international community as constituting extreme poverty.

If I may be permitted to quote, out of context, a sentence taken from the great novel Allah is not obliged, published in French in 2000 by the great Ivorian writer and athlete Ahmadou Kourouma, there is no justice on this Earth for the poor.

Alfred Champagnat. J.W.G. Wignall, “Food From Crude Oil May Feed Hungry.” The Age TV and Radio Guide, 17-23 May 1963, 13.

Would you like to learn more about Champagnat’s work? And, yes, that was indeed a rhetorical question. Sorry.

Producing food proteins from petroleum might have seemed like a joke in bad taste, no pun intended, but it was nevertheless the gamble that Champagnat took on.

This being said (typed?), Champagnat was not the first researcher to carry out work in that area. Nay. In fact, the American electrochemical engineer John Woods Beckman had suggested the use of microorganisms to produce food proteins as early as 1926.

In 1948, West German researchers Felix Just and W. Schnabel successfully cultivated bacteria on liquid and solid paraffins. They obtained one unit of mass (gram or ounce, your choice) of powder per unit of mass of liquid paraffin, for example. Just and Schnabel offered the powder thus obtained to rats which consumed it without apparent negative effects. Those two researchers subsequently carried out work with yeasts, work which also gave good results. In 1951, Just and Schnabel collaborated with another West German researcher, S. Ullmann, and again obtained high yields.

Yet another West German researcher, W. Hoerburger, carried out experiments in 1955 but did not believe that those could give rise to an industrial application, but back to Champagnat.

According to some, it was during an informal meal at lunchtime that Champagnat’s project began. He was then breaking bread with a colleague, Charles Vernet, and a microbiologist from the prestigious Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) stationed in Marseille, Jacques Charles Senez. The latter had been collaborating with researchers from the Société française des pétroles BP since 1956 on biological processes for cleaning water contaminated by hydrocarbons. That project, it seemed, had not delivered the results everyone had hoped for.

Champagnat having asked him if he had any ideas for continuing their collaboration, Senez proposed the production of food proteins with petroleum. Champagnat and Vernet being visibly skeptical, Senez explained to them what was on his mind. Skepticism gave way to enthusiasm.

Mind you, other sources suggested that the idea had come from Champagnat who then mentioned it to Senez.

In any event, with the financial resources of the Société française des pétroles BP and the support of the CNRS, Champagnat embarked on the adventure, an adventure which will continue next week.

Until then, enjoy yourself carefully, my reading friend. Moderation is not just for monks.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)