“Lector, si monumentum requiris, circumspice.” – Remembering Robert William “Bob” Bradford (1923-2023), Part 1

It is with a profound sadness that I begin this issue of our blog. Indeed, it had been my hope that the remarkable individual at the heart of it might have been able to read this commemoration of his 100th anniversary – and suggest an improvement or two in his inimitable and very gentlemanly fashion. Sadly, this was not to be.

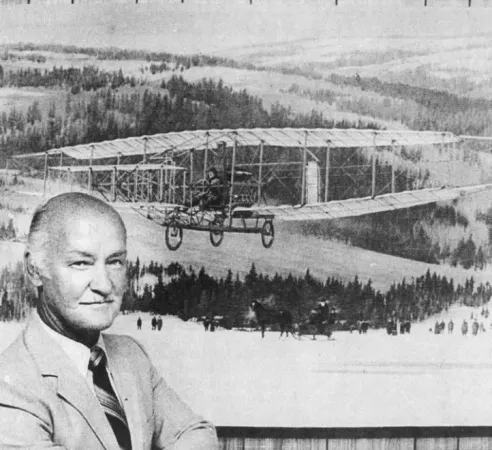

Robert William “Bob” Bradford and his twin brother James “Jim” Bradford were born in Toronto, Ontario, on 17 December 1923, twenty years to the day after the first sustained and controlled flight of a powered aeroplane, made by the Wright brothers at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

Bradford and his brother developed their love of sketching and painting while attending Saturday morning classes at the Art Gallery of Toronto.

Even though Bradford was later on a part time student at the Ontario College of Art, also in Toronto, one could argue that he was a self-taught artist – and a spectacularly gifted one at that.

By the late 1930s, Bradford was working for Easybuilt Model Aeroplane Company of Toronto where he designed and built rubber-powered balsa wood airplanes for youngsters.

He took his first flying lesson at the age of 17. By then, the world was at war.

Bradford and his brother joined the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) together at age 18 and became pilots.

Bradford was one of 130 000 or so pilots, navigators, gunners, etc., from all over the Commonwealth and beyond who learned their trade between 1940 and 1945 in the many specialised schools of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, one of the greatest contributions of Canada to the victory of the Allies in the Second World War.

Incidentally, Bradford learned to fly at an elementary flying training school, more specifically No. 6 Elementary Flying Training School, located in RCAF Station Prince Albert, located near the city of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. The aircraft he trained on were de Havilland Tiger Moths, a type of aircraft represented in the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario.

Bradford graduated from a service flying training school, probably No. 19 Service Flying Training School, located in RCAF Station Vulcan, near the town of Vulcan, Alberta. The aircraft he trained on were seemingly Avro Ansons, another type of aircraft represented in the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

Flying Officer Robert William Bradford of the Royal Canadian Air Force, near Blackburn, England, Summer 1944. CASM, 13809.

Bradford was posted overseas in March 1944 and became a staff pilot with the Royal Air Force. Incidentally, he was stationed on the Isle of Man, England.

Bradford was seriously injured in November in a flying accident and spent several months in hospital. He was about to return to operational duties when the Second World War ended.

Once back in Toronto, Bradford went back to Easybuilt Model Aeroplane and attended night classes at the Ontario College of Art.

Bradford joined the staff of an important aircraft manufacturing firm, A.V. Roe Canada Limited of Malton, Ontario, in 1949, where he worked as a technical illustrator.

Bradford’s work as a non aeronautical artist was recognised by the committee which organised a contemporary art exhibition in Toronto in 1951 (?) that I have not been able to identify. That exhibition was quite important indeed: works from five members of the famous Group of Seven were on display.

Another important aircraft manufacturing firm, de Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited (DHC) of Downsview, Ontario, hired Bradford as a project illustrator in 1953. He became Chief Illustrator in the firm’s Publications Department in 1956 and seemingly remained there until 1966, a very significant year in the life of that main character of our story.

Before we get there, however, let us peer at a few advertisements which included artwork made by Bradford.

A typical de Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited advertisement which shows the prototype of the de Havilland Canada Otter. Anon., “De Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited.” Canadian Aviation, July 1953, 22.

A typical de Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited advertisement which shows an agricultural spraying version of the de Havilland Canada Beaver. Anon., “De Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited.” Flight, 22 October 1954, 21 (advertisement page).

A typical de Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited advertisement which shows a de Havilland Canada Caribou. Anon., “De Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited.” Flight, 6 February 1959, between pages 180 and 181.

A typical de Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited advertisement which shows a de Havilland Canada Otter operated by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police during a January 1959 rescue operation in the Canadian North. Anon., “De Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited.” Flight, 5 June 1959, 3rd cover.

In 1961, the founding curator of the recently created National Aviation Museum, in Ottawa, today’s Canada Aviation and Space Museum, came across a 1962 calendar produced by Rolph-Clark-Stone Limited of Toronto. Said calendar included 4 paintings by Bradford, including one of a Curtiss JN-4 Canuck training biplane used to train pilots in Canada during the First World War. Kenneth Meredith “Ken” Molson was impressed.

Molson was so impressed that he commissioned Bradford to do a series of paintings on some of the highlights of early Canadian aviation. This, in turn, led Molson to encourage the artist to leave DHC and join the museum, which he did, in 1966, to become Assistant Curator.

At the time, the National Aviation Museum was located in the new terminal building of Uplands Airport, today’s Ottawa Macdonald–Cartier International Airport, when it opened its doors to the public in October 1960.

Incidentally, the series of paintings originated from a realisation that each and every photographic representation of the early years of aviation in Canada was in black and white.

It was Molson’s hope that Bradford would be able to complete 4 paintings a year and keep this up for several years. Sadly, however, the art program came to a close in 1967.

And here are few of the 16 (?) accurate and appealing works of art made between 1962 and 1966-67.

Avro Canada C-102 Jetliner (circa 1962, watercolour on board), which depicts the one and only Avro Canada C-102 Jetliner jet powered airliner, Malton, Ontario, August 1949. CASM, 1967.0887.

Canadian Vickers Vedette Mk Va over Montreal (circa 1963, watercolour on board), which depicts a Vickers Vedette flying boat operated by the Civil Government Air Operations of the Department if National Defence, Montréal, Québec, circa 1930. CASM, 1967.0897.

John Webster in the King’s Cup Race (circa 1964, watercolour on board), which depicts the Curtiss-Reid Rambler light / private aircraft piloted by John Clarence Webster, Junior, during the 1931 edition of the King’s Cup Race, England, July 1931. CASM, 1967.0898.

A.E.A. Silver Dart (circa 1965, acrylic on board), which depicts the first flight of the Aerial Experiment Association Aerodrome No. 4 Silver Dart on Canadian soil, Baddeck, Nova Scotia, February 1909. CASM, 1967.0893.

Curtiss HS-2L Flying Boat (circa 1966, acrylic on board), which depicts a Curtiss HS-2L of the Canadian Air Board used for the first trans-Canada flight, Rivière-du-Loup, Québec, October 1920. CASM, 1967.0885.

By 1966, the aircraft collection of the National Aviation Museum had been merged with those of the RCAF and of the Ottawa-based Canadian War Museum to form the National Aeronautical Collection. That merged collection, opened to the public in May 1965, became part of the National Museum of Science and Technology, in Ottawa, a national museum of Canada founded in 1967.

Incidentally, that museal institution was one of the national museums which formed National Museums of Canada Corporation, a crown corporation created in the spring of 1967.

At the time, the National Aeronautical Collection was to be found in Second World War era wooden hangars located on the grounds of RCAF Station Rockcliffe, in Rockcliffe, Ontario.

Bradford became Curator of the Aviation and Space Division of the National Museum of Science and Technology in 1967, when Molson retired.

It is worth noting that the daily activities of a national museum of Canada curator were and still are varied in the extreme. That individual may spend days writing exhibition texts that creative development specialists gently deconstruct, hours escorting groups of very important people who would rather be elsewhere, or minutes answering the often surprisingly insightful questions of groups of 6 year old children.

Other activities could be a tad more unusual, however. One only needs to mention a hot air balloon flight made on 29 June 1968 on the grounds of the National Museum of Science and Technology by Bradford and the pilot of Spirit of Canada, the first hot air balloon registered in Canada, Stanley John Sheldrake.

The first hot air balloon registered in Canada in flight above the National Museum of Science and Technology, Ottawa, Ontario, 29 June 1968. A delighted Robert William Bradford, Curator of the Aviation and Space Division of that museal institution, flew that day with the pilot of Spirit of Canada, Stanley John Sheldrake. Anon., “Up, up, up and away.” The Ottawa Citizen, 2 July 1968, 10.

Incidentally, Spirit of Canada also carried 300 or so envelopes which commemorated that flight as well as the one made in Ottawa, Canada West, in June 1858 by the famous American aeronaut / inventor Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe. That particular balloon flight, made with a gas balloon by the way, was the first ever made in Ottawa.

It should be noted that Spirit of Canada is one the flying machines in the amazing collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

In September 1968, Bradford took to the sky yet again. That aerial journey was done in a helicopter provided by the Department of Lands and Forests of Ontario, however. The Bell Model 206 used on that occasion was very similar to the Bell CH-136 Kiowa stored in the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

The flight in question was instigated to confirm the sighting of an aircraft in a small unnamed lake located not too far from Kapuskasing, Ontario. The presence of an aircraft was quickly established. The gentle use of a pulp hook allowed Bradford to confirm that said aircraft was a Curtiss HS-2L, a type of flying boat used for bush flying in the 1920s. That discovery led to the identification of the aircraft in question as G-CAAC, La Vigilance, the very first bushplane flown in Canada, which had been lost as a result of a crash on a small unnamed lake located not too far from Kapuskasing, in September 1922.

A beaming Robert William Bradford holding a clearly identified component of the Curtiss HS-2L known as La Vigilance, unnamed lake, Ontario, circa 1968-69. CASM, 15479.

The precious remains of the HS-2L were carefully extracted from the mud of the lake during the summer of 1969. Airlifted to Kapuskasing by a helicopter of the Canadian Armed Forces, the treated remains were carefully put on at least one truck for the long journey to Ottawa.

The hull of La Vigilance is presently on display in the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

In 1973, the staff of the National Aviation Museum began the construction of a full-size reproduction / replica of an HS-2L. That astounding project was completed in June 1986. That aircraft is presently on display in the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

The 1969 Canadian stamp which commemorated the 50th anniversary of the first nonstop crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, in May 1919, by an English pilot, John William Alcock, and his Scottish navigator, Arthur Whitten Brown. CASM, 1998.0567.

As preparations for the recovery of the HS-2L took place, Bradford was involved with the design of a stamp which commemorated the 50th anniversary of the first nonstop crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, in June 1919, by an English pilot, John William Alcock, and his Scottish navigator, Arthur Whitten Brown. The Post Office Department unveiled that stamp in June 1969.

As you may well imagine, the HS-2L was not the only aircraft acquired by Bradford and his right-hand man, Alfred John “Fred” Shortt. Indeed, the collection of what was then the National Aviation Museum grew from 45 or so aircraft in 1966 to 90 or so aircraft in 1988, when Bradford retired – an increase of 100 or so percent.

I shall complete my brief tribute to the late Robert William Bradford next week.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)