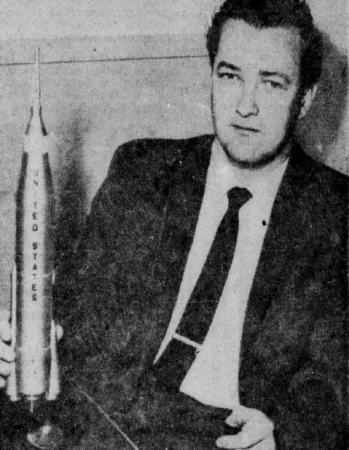

The little guy from Sarnia who put the first human on the Moon

If I may be permitted to paraphrase Lawrence Henry Gowan, a Scottish Canadian singer, Homo sapiens is a strange animal. Our history can be the best of times. It can also be the worst of times, if I may paraphrase Charles John Huffam Dickens. All of this to say (type?) that July 2019 was / is quite the month from an anniversarial point of view. Fifty years ago this month, a human, 2 humans actually, set foot on an extraterrestrial body. And what a body! The Moon, to paraphrase the title of a 1966 science fiction novel by Robert Anson Heinlein, was / is a harsh mistress. Would you believe that the theme for this week’s pontification has to do with our companion in the darkness of space, the final frontier? Would you accept anything else? And yes, yours truly is trying to pack as many clichés and quotes as I can in this opening paragraph.

Incidentally, Heinlein, one of the most influential if somewhat controversial science fiction writers of the 20th century, was mentioned in a February 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, but enough twaddle, for now.

Our story began in Sarnia, Ontario, in October 1924. Our hero was / is Owen Eugene Maynard. And yes, the ancestors of this anglophone gentleman may well have been called Ménard, a good French name. You might be surprised to hear (read?) that some French speaking Quebecers made it big in the United States in the 19th and 20th century. You will undoubtedly remember Antoine “Anthony” Chabot, the “Water King” mentioned in a May 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, and … You don’t, now do you? Sigh. I presume, then, that you have never heard of Jean Cantius “John” Garand or Domina Cléophas “Dom” Jalbert. These gentlemen from Québec developed, on the one hand, the standard rifle that the United States Army used during the Second World War, and after, the M1 or Garand rifle, as well as something else, on the other, but back to our story. And no, yours truly will not tell you what Jalbert developed because I might, I repeat might, write an article on him at some point in the future.

Maynard left school at age 16, in 1940. He worked as a boat builder and machinist for some time before enlisting in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). Maynard became a pilot and eventually learned to fly one of the most versatile machines of that conflict, the de Havilland Mosquito twin engine 2-seat multi role combat aircraft – a British type made in Canada represented in the amazing collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario. Maynard flew one of the bomber versions of the “Wooden Wonder,” as this remarkable machine was sometimes / often called. While he did end up in the United Kingdom, the Second World War seemingly ended before he could see combat.

What’s this I hear? Can it be true? Really? Yes! To paraphrase the Thing, one of Fantastic Four, a superhero team you should know and love, it’s digressing time! And yes, the Fantastic Four were / are among the countless superheroes developed for Marvel Comics Incorporated, a firm known in 2019 as Marvel Worldwide Incorporated mentioned in a February 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. Bur back to our digression.

The year was 1941. At that time, a new aircraft, the aforementioned Mosquito, aroused much enthusiasm. Contacted by the British Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP), the Canadian Department of Munitions and Supply signed a contract in September with de Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited (DHC), a well-known aircraft manufacturer in Toronto, Ontario, and a subsidiary of the British aircraft maker de Havilland Aircraft Company Limited, for 400 aircraft of this type, for the Royal Air Force (RAF). All materials, including engines, had to originate in North America and be assembled using a North American production system. These choices caused some turmoil in the United Kingdom. Indeed, Canadian and British Mosquitos would not be interchangeable.

Even before the end of the year, the MAP was also facing a serious problem. The Department of Munitions and Supply believed that DHC would produce long-range fighter planes that would very suitable for the defence of Canada, a vast country if there was one. It realized a tad late that the Toronto aircraft manufacturer would build bombers. The Director General of Aeronautical Production, Ralph Pickard Bell, felt betrayed. He contacted the MAP to open a second assembly line or negotiate an amendment to the contract. The British, a little surprised and embarrassed, refused. It was too late; production would soon start.

Bell was very unhappy. This way of doing, he said,

[was] typical of our contracts throughout with the British on aircraft and I am sorry that we ever touched the thing [… ] It is one of those completely unfortunate situations and, so far as I am concerned, it is the last time I will have a thing to do with British aircraft in Canada. I should have learned my lesson earlier on this.

This being said (typed?), he did not admit defeat.

In the spring of 1942, the Department of Munitions and Supply tried to order about 250 Mosquito fighter planes. While the MAP did not see any objections, the fact was that the Mosquito production program was facing many delays. Talks went nowhere. Many factors contributed to the aircraft manufacturer’s setbacks, but the fact was that the Department of Munitions and Supply had good reasons to worry.

A stormy meeting with the DHC leadership in the spring of 1943 touched off a crisis. The Governor General of Canada, the Earl of Athlone, born Alexander Cambridge, signed an order in council which put in place a controller with full powers of action, John Grant Glassco. This being said (typed?), it was not until the beginning of 1944 that DHC managed to overcome its difficulties. Glassco resigned in September and returned to private law practice. The all-powerful minister of Munitions and Supply, Clarence Decatur “C.D.” Howe, then set up a control committee which gave excellent results. DHC did not regain its independence until August 1945, at the end of the Second World War.

And yes, my reading friend, Howe was mentioned in an April 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

The first Canadian Mosquito, which included some British pieces of equipment, flew in September 1942, about 3 months after the signing of a second contract for 1 100 additional bombers funded by the United States through the Lend-Lease Act. At that time, however, the RAF was increasingly interested in a new version of the Mosquito which combined the armament of the fighter plane and the bomb bay of the bomber plane. In the spring of 1943, the MAP required that the production line in Canada be modified accordingly. Over time, the MAP and the Department of Munitions and Supply decided to produce fighter bombers and advanced trainers.

While all Canadian fighter bombers produced by DHC were initially destined for the RAF, the RCAF and the Department of Munitions and Supply managed to negotiate the transfer of nearly 200 aircraft serving in operational training units based on Canadian soil from February 1945. They joined nearly 250 Mosquito bombers and advanced training aircraft used by these units since the spring of 1943. In the end, the RCAF received a little less than 450 Mosquito produced in this country.

The American armed forces were also interested in the Mosquito. The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), for example, repeatedly tried to organise exchanges with the MAP to obtain 200 British-made photographic reconnaissance aircraft. These projects failed. This version was only produced in small quantities and de Havilland Aircraft was not able to provide these aircraft within the required time frame. The USAAF finally resigned themselves to accept 40 Canadian de Havilland F-8 Mosquito delivered from June 1943 onward. Their performances being inferior to that of the most recent British Mosquitos, the USAAF did not accept other Canadian aircraft. Various manufacturing quality issues also seemed to affect some of these Mosquitos.

Be that as it may, the United States Navy also began discussions with the MAP early in 1943. It wanted to use 150 Canadian Mosquitos equipped with radar, and destined for night fighting, in the Pacific theater of operations. The MAP refused. The governments of China and the Soviet Union also failed in their efforts.

It should be noted that DHC supplied tools and parts to a sister company, de Havilland Aircraft Proprietary Limited, also a subsidiary of de Havilland Aircraft, through the Lend-Lease Act, to help launch production of the Mosquito in Australia. These aircraft served in squadrons of the Royal Australian Air Force.

After several very difficult months, Canadian Mosquito production peaked in 1944. DHC produced just over 1 030 Mosquito, all versions included, between 1942 and the end of the Second World War. Nearly 470 aircraft were canceled. The Mosquito was / is one of the most successful combat aircraft of the 20th century. And yes, it was mentioned in a June 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

The saga of the Canadian Mosquito does not end with the end of the Second World War, however. Indeed, the federal government had an interest in getting rid of aircraft, manufactured in Canada in most cases, that it no longer needed. The sale of used aircraft by the War Assets Corporation, a crown corporation, however, seriously undermined the efforts of Canadian aircraft manufacturers. In some cases, the federal government appeared to be somewhat rapacious. In 1947, for example, the Chinese government negotiated the terms of a loan in the utmost secrecy. Indeed, the situation in China, then struggling with a civil war, was deteriorating from one hour to the next. The federal government was aware of this. Although anxious not to get involved in this conflict, it pressed its advantage. To obtain its loan, the Chinese government had to buy almost all Mosquito fighter bombers still available in Canada, including 100 or so aircraft completed by DHC after the end of the Second World War.

The delivery of all these aircraft as well as the sending of a few Canadians to train the crews was done without too much publicity. Approximately 205 Canadian Mosquitos arrived in China by the spring of 1948. All these efforts proved futile. Even before the end of September 1949, Mao Ze Dong proclaimed the birth of the People’s Republic of China.

This digression was rather depressing, was it not? Let us now return to the topic at hand.

At some point in the second half of the 1940s, Maynard joined the staff of Malton, Ontario, based A.V. Roe Canada Limited (Avro Canada), a subsidiary of A.V. Roe & Company Limited, itself a subsidiary of a British aeronautical giant, Hawker-Siddeley Aircraft Company Limited / Hawker-Siddeley Group Limited. Among other things, he worked on the layout of the Avro Canada C-102 Jetliner, in the late 1940s, as well as on the missile pack and landing gear of the Avro CF-105 Arrow, in the 1950s. Maynard did part of this work while completing a bachelor’s degree in aeronautical engineering at the University of Toronto, in Toronto, Ontario. He graduated in 1951, by the way.

The Jetliner, test flown in August 1949, was the first jet powered airliner to fly in North America and the second to fly in the world. For a variety of reasons, this promising machine was not put in production. The Arrow, on the other hand, was test flown in March 1958. For a variety of reasons, this highly promising supersonic all weather bomber interceptor was not put in production either. Worse still, almost all employees working on the project were fired on the day the project was canceled by the Canadian government, 20 February 1959, or Black Friday. And yes, the Arrow was mentioned in several issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since February 2018.

Shortly after the cancellation of the Arrow, Avro Canada’s management contacted the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to offer it the services of a group of 25 to 30 Canadian and British engineers and researchers recently made unemployed. Surprised but delighted, the American organisation assigned these people to the Mercury piloted space program and other projects. Their departure was part of a vast exodus of talented individuals who abandoned Canada for the benefit of the United States, the United Kingdom and elsewhere.

And yes, NASA was mentioned in several issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since March 2018.

Maynard worked on the Mercury programme in 1959-60. He was one of the few engineers at NASA’s Space Task Group, a working group which became the Manned Spacecraft Center, the ancestor of today’s Johnson Space Center, to be assigned, in 1960, to the Advanced Vehicle Team. Said team was to conduct research and make preliminary drawings of a new multiseat space capsule, presumably for a brand new piloted space programme. Back then, the Apollo, yes, Apollo, programme had no specific goal. Would you believe it did not even have an authorisation to proceed? And yes, the Manned Spacecraft Center and the Apollo programme were mentioned in a June 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

In 1961, Maynard was involved in the recovery of the remains of an unpiloted Convair Atlas launch vehicle / rocket which had crashed in April off the coast of Florida after going off course. He seemingly dove in the water himself to bring up a particular piece of the McDonnell Mercury space capsule carried by the rocket. Said capsule was later recovered. This flight was NASA’s first attempt to put a Mercury space capsule in orbit. It succeeded in September 1961.

Maynard contributed to the original designs of what eventually became the Apollo Command Module and the Apollo Service Module of the world famous spacecraft. He was one of the first members of the Space Task Group to favour the lunar orbit rendezvous approach used for all the Moon landings of the Apollo programme. Maynard drew the first serious sketches of what eventually became the Apollo Lunar Module / Lunar Excursion Module. Better yet, the Space Task Group used these very sketches to convince NASA’s bigwigs that the lunar orbit rendezvous approach was the best one for the job. Would you believe that the Apollo Lunar Module was mentioned in a June 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee?

By 1963, Maynard headed the Apollo Lunar Module office of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office at the Manned Spacecraft Centre. While it is true that Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation built each and every Apollo Lunar Module, Maynard was the one person most responsible for the design of this unique vehicle.

In 1964, Maynard was given the position of chief of the systems engineering division of the Apollo Spacecraft Program. While it is true that he was not the chief engineer of the Apollo programme, Maynard was responsible for making sure that all the parts of an Apollo spacecraft functioned perfectly together, as well as with the gigantic Saturn V launch vehicle / rocket and all ground facilities.

Maynard became head of the mission operations division of the Apollo Spacecraft Program in 1966. No too long after the January 1967 Apollo 1 fire which took the lives of 3 astronauts, he was transferred back to the systems engineering division. Before the end of that year, Maynard and his team had drawn up a mission sequence that led to a first Moon landing, on the 7th flight. As we both know, Apollo 11 landed on the Moon in July 1969 – 50 years ago this month. And yes, this historic mission was mentioned in May and June 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

In recognition of his many achievements, Maynard received 2 NASA Exceptional Service Medals in 1969.

Maynard left NASA in 1970. He then began another phase of his aerospace career at Raytheon Company. Maynard promoted the construction of gigantic satellites to collect solar power that could be used on Earth. He also promoted the use of solar power collected on this Earth to power spacecraft. These projects went nowhere. While at Raytheon, Maynard may, I repeat may, have worked at least some time with William C. Brown, the father of microwave wireless power transmission and a gentleman mentioned in a January 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Solar-power satellites were / are quite fascinating. Peter Glaser, an employee of Arthur D. Little Incorporated, an American management consulting firm, came up with this game changing concept in 1968. While there was much interest on this technology as a result of the 1973 oil crisis, the joint Department of Energy / NASA solar-power satellite development and evaluation program came to a close in 1980, 3 or so years after it had begun. Cost and technical issues presumably played a major part in this decision. Public concerns regarding the health and environmental impact of the microwaves beamed down to Earth may have played a (small?) role as well. There was no follow up research and development program. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics apparently looked into solar-power satellites in the mid-1980s but nothing came of it.

Maynard retired in 1992. He returned to Canada soon after, settling in Waterloo, Ontario, with his spouse. This space pioneer died in July 2000. He was 75 years old.

I do hope that this article was of some limited interest to you. Be well.

P.S. On a very sad note, please note that 2 of the 3 brave men who perished in the Apollo 1 fire of January 1967, namely Virgil Ivan “Gus” Grissom and Edward Higgins “Ed” White II, were mentioned in previous issues (July and September 2018, and June 2019) of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)