Sorry, but no, the Wright brothers did not really invent the airplane: An all too brief overview of the piloted powered heavier than air flying machines fabricated and / or tested before 17 December 1903, part 4

Bonjour, ami(e) lectrice ou lecteur, hello, my reading friend, and welcome to the 4th and final part of our all too brief overview of the piloted powered heavier than air flying machines fabricated and / or tested before 17 December 1903.

Let us begin.

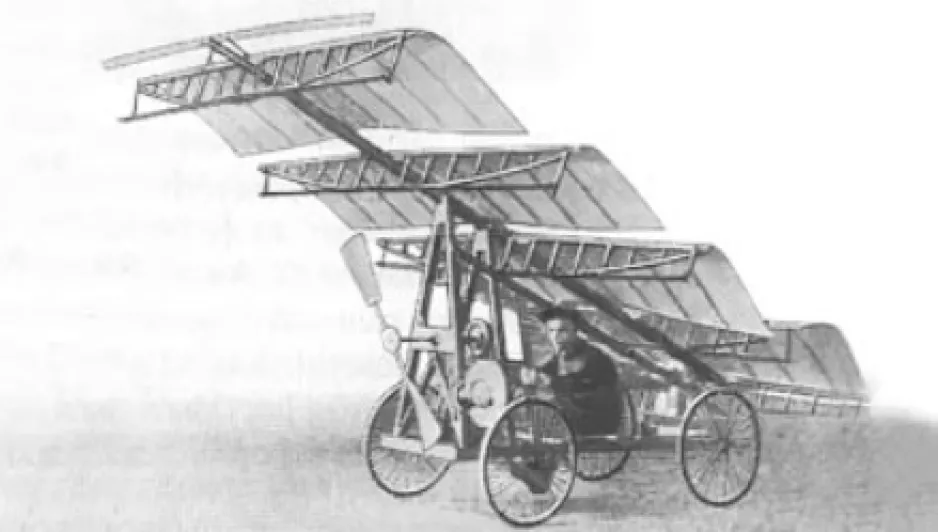

The Chicago Bird multi-wing ornithopter designed by William C. Horgan, Chicago, Illinois. Anon., “Horgan’s Flying Machine.” The Aëronautical World, 1 January 1903, 131.

William C. Horgan (?-?) was a Canadian American mason contractor / surveyor who, in Chicago, Illinois, in December 1902 or January 1903, completed a two-seat, yes, two-seat, ornithopter whose gasoline engine activated 6 pairs of wings mounted in tandem.

As far as yours truly can figure out, that Chicago Bird had been preceded by two human-powered ornithopters completed in the same location in 1900 and 1902.

Horgan drew his inspiration for all of his flying machines from a “devil’s darning needle,” in other words a dragonfly, which had flown around him around 1892, as he worked with a surveying party on the site of the future Illinois and Mississippi Canal, in Illinois.

Were you familiar with that nickname, my reading friend? I certainly was not.

Incidentally, Horgan planned to go to St. Louis, Missouri, where would be held, between April and December 1904, an international exposition / world fair, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, the most stupendous entertainment the world had ever seen, if yours truly may paraphrase the ballyhoo of a newspaper headline of the time. If truth be told, he got in touch with fair officials no later than March 1902.

Why did Horgan want to go to St. Louis, you ask? A good question. You see, one of the many attractions of the world fair, besides the Games of the III Olympiad, was an aeronautical competition with a grand prize of no less than US $ 100 000. To earn this truly titanic sum of money, which corresponds to about 4 750 000 $ in 2024 Canadian currency, a pilot only needed to go around a 16-kilometre (10 miles) circuit 3 times. Easy peasey.

In the end, however, Horgan did not attend that world fair with his Chicago Bird and no, that motorised ornithopter never flew.

The small firm founded no later than March 1902 by Horgan and a few partners / investors, Chicago Bird Flying Ship Company, presumably folded at some point around the mid 1900s. That firm did not accomplish much before it vanished.

Horgan and a few partners / investors incorporated Horgan Flying Machine Company of Chicago in February 1909 but that firm did not accomplish much either before it vanished.

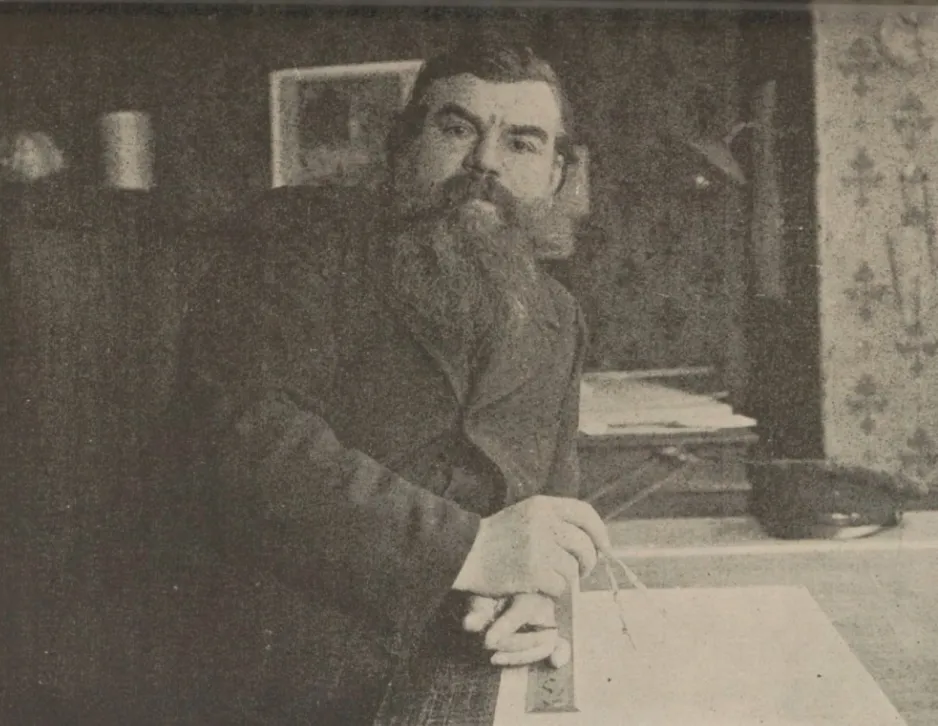

Captain Louis Ferdinand Ferber. Anon., “Portraits d’aéronautes contemporains – Capitaine Ferber.” L’Aérophile, February 1905, 25.

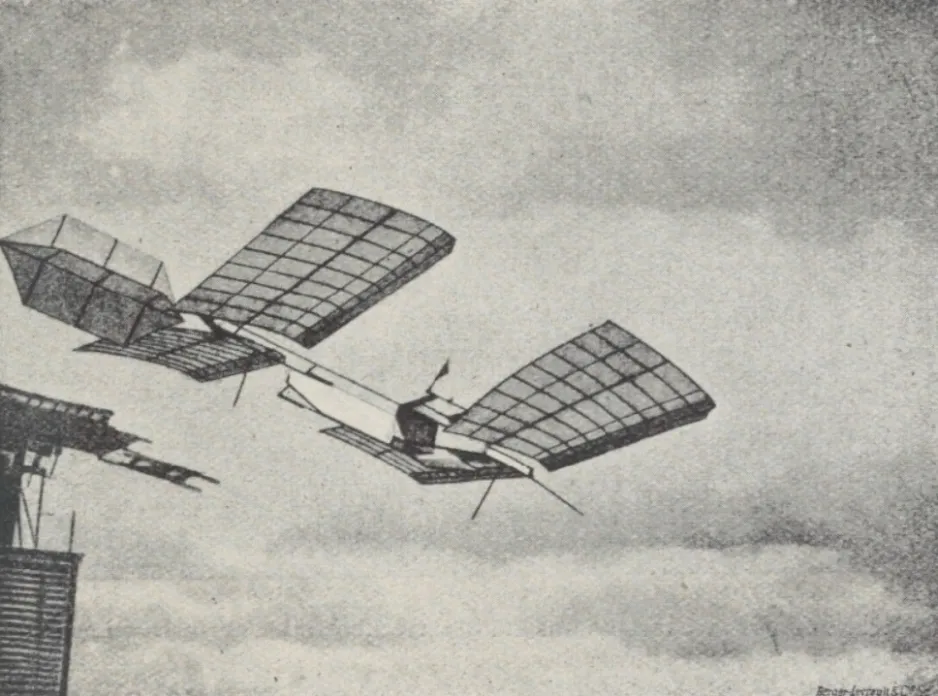

The Ferber No. 6 aeroplane designed by Captain Louis Ferdinand Ferber, Nice, France, June 1903. That aeroplane was tested using a rotating arm mounted on a tower. Ferdinand Ferber, L’aviation, ses débuts, son développement : De crête à crête, de ville à ville, de continent à continent. (Paris: Berger-Levrault, 1908), 63.

Captain Louis Ferdinand Ferber (1862-1909) was a French Armée de Terre artillery officer / instructor who, in the late spring of 1903, mounted a gasoline engine on a biplane glider he had completed in or near Nice, in the Provence region of France, in early 1903. Initially tested near Le Conquet / Konk-Leon, in the Britanny region of France, that glider was inspired by information sent to him by Octave Chanute, a French American civil engineer and aviation pioneer who knew the Wright brothers and what they were up to.

Ferber tested that powered aeroplane, his first, the Ferber No. 6, with the 18 or so metre (59 or so feet) high rotating tower, or aérodrome, whose construction he had supervised in or near Nice, in late 1902, to reduce the risk of accidents.

Ferber had built and tested his first glider in 1899, at Fontainebleau, France, near Paris, where he was stationed, a year or so after reading a text about the experiments conducted by Karl Wilhelm Otto Lilienthal, a German inventor / industrialist / theatre director / author / amateur actor mentioned in the second part of this article.

Encouraged by the letters he exchanged with the Wright brothers, Ferber continued to experiment. First tested on the ground in May 1905, at Chalais-Meudon, France, near Paris, his Ferber No. 6 aeroplane proved unable to take off.

Ferber did not even attempt to take off aboard his Ferber No. 7. That aeroplane was quickly used to test propellers.

The much improved gasoline-powered Ferber No. 8 monoplane was destroyed in a storm, in November 1906, at Chalais-Meudon, before it could be tested.

Granted a leave of absence by the Armée de Terre during that year, Ferber joined the staff of a newly created French manufacturer of light yet powerful engines, the Société Antoinette. He did so mainly because his superiors seemed unable to understand the military potential of a practical aeroplane.

In any event, Ferber supervised later on the construction of the Ferber No. 9, an aeroplane all but identical to its unfortunate predecessor. Completed in July 1908 and quickly renamed Antoinette III, that aeroplane lifted off for the first time that some month, at the Armée de Terre parade ground of Issy-les-Moulineaux, in the suburbs of Paris. Ferber and at least another aviator piloted that machine on many occasions.

Tragically, Ferber died in September 1909, soon after the aeroplane he was taxiing ran into a ditch and flipped over. He was then only 47 years old.

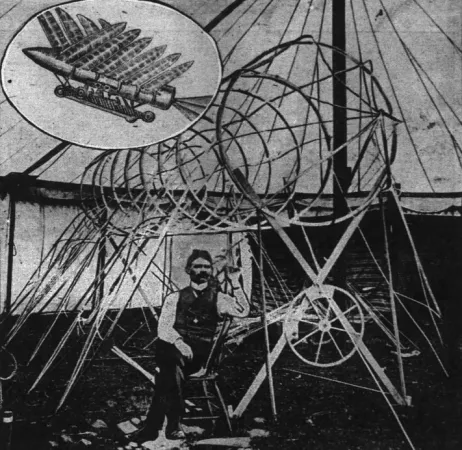

The flying machine completed in 1903 by Yevgeniy Stepanovich Fedorov. Wikipedia.

Yevgeniy Stepanovich Fedorov (1851-1909) was a Russian military engineer who began to build a gasoline-powered aeroplane whose 5 wings were staggered at a 45 degree angle, in 1896-97, in Sankt-Peterburg / Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire. He seemingly completed that flying machine in 1903. Reoccurring mechanical issues prevented Fedorov from testing it – and finding out his creation would never fly.

Karl Jatho, circa 1907-08. Wikipedia.

The rebuilt triplane aeroplane that Karl Jatho might have tested in August 1903 on display at the Internationale Sport-Ausstellung Berlin 1907, Berlin, German Empire, April-May 1907. Wikipedia.

Karl Jatho (1873-1933) was a German civil servant who, according to his notebooks, completed a gasoline powered aeroplane no later than August 1903, in Hannover / Hanover, German Empire. He managed to make an uncontrolled 18 or so metre (60 or so feet) hop on 18 August. Damaged before the end of that month when it overturned, that triplane was turned into a biplane over the next month, I think. By November 1903, Jatho claimed to have covered, seemingly with little control, a distance of 60 or so metres (195 or so feet).

The catch with those statements was that no trace of a single article has been found in German newspapers of the time. Worse still perhaps, the work conducted in Jatho’s notebooks really began 1933, possibly after the March 1933 election which saw Adolf Hitler’s highly nationalistic and violent Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP) become the dominant political party in Germany.

If truth be told, the first newspapers articles detailing Jatho’s efforts to fly seemed to date from March 1907. His first flight might have occurred only in 1908. Jatho might, I repeat might, have completed 3 or 4 aeroplanes between 1907 and 1909.

It is worth noting that the rebuilt triplane aeroplane that Karl Jatho might have tested in August 1903 was on display at the Internationale Sport-Ausstellung Berlin 1907, held in Berlin, German Empire, in April and May 1907.

In November 1913, Jatho founded Hannoversche Flugzeugwerke Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung. Neither that aeroplane manufacturing firm nor the flying school associated with it caught the eye of the Deutsches Heer or the Kaiserliche Marine, in other words the German army and imperial navy. As a result, both of them closed in 1914.

In any event, a monument was unveiled, in October 1933, in the presence of an elderly Jatho, at what was then the airport of Hanover, a monument with the NSDAP eagle and swastika which included the word Jatho and the date 18 August 1903 with in between the following words, translated here, The first powered aircraft of the world, an utterly inaccurate statement as we both know by now.

Would you believe that a replica of Jatho’s aeroplane whose accuracy cannot be ascertained was built so that it would fly on the day of the ceremony? Bad weather prevented that flight from taking place, however.

Put on display at the airport in the fall of 1933, the replica moved to Berlin in 1936, when it became one of the aircraft of the Deutsche Luftfahrtsammlung, the most impressive aviation museum in Europe. It was presumably destroyed during one of the two 1943 and 1944 Allied bombings raids which pulverised many if not most of the aircraft in the museum’s collection.

Another replica was completed in 2006 as part of the German Wir waren die Ersten project, Wir waren die Ersten meaning We were the first, an utterly inaccurate statement as we both know by now. Bad weather, in September, prevented a test flight from taking place.

As of 2024, that replica was on display in the Welt der Luftfahrt exhibition at the Flughafen Hannover, one of the busiest airports in Germany, in Langenhagen.

Also in 2006, a regional history working group, the Arbeitskreis Stadtteilgeschichte List, unveiled a memorial stone dedicated to Jatho on the site where the August 1903 flight had allegedly taken place.

Léon Marie Levavasseur. François Peyrey. L’Idée aérienne – Aviation – Les Oiseaux artificiels. (Paris: H. Dunod et E. Pinat, 1909), 417.

Léon Marie Levavasseur (1863-1922) was a French electrical engineer who, in 1903, designed a monoplane aeroplane with the financial assistance of a French industrialist, Jules Adrien Gastambide, and of the French Ministère de la Guerre. The Levavasseur No. 1 was put together in the spring and, possibly, the early summer of 1903, at Suresnes, in the suburbs of Paris, by the staff of the Société du propulseur amovible

Tested at Villotran, France, near Beauvais, not too, too far from Paris, in August and September, by Levavasseur’s colleague and brother-in-law, Charles Wachter, the large and heavy machine proved unable to take off from the track it had been placed on. In late September, the Levavasseur No. 1 left that track during a test and suffered serious damage. A storm later completed the destruction of the aeroplane.

The powerplant of the Levavasseur No. 1 was an early example of a very advanced gasoline engine designed by Levavasseur. Derivatives of that powerful yet light engine, quite possibly the first V-8 engine in the world, soon gained fame when mounted on a series of racing boats bearing the first surname of Gastambide’s daughter, Antoinette Émilie Léonie Gastambide.

Better yet, when, in May 1906, I think, Gastambide and Levavasseur founded a firm to produce the latter’s engines, they kept that name and thus was born the Société Antoinette. One could argue that course of aviation would have been very different had that firm and its engines not existed.

Incidentally, one of the individuals who had invested in the Société Antoinette very early on was a French engineer / industrialist / aviation pioneer you might have heard of, Louis Charles Joseph Blériot. Yep, that Blériot, the one who crossed the Channel, between France and England, in July 1909.

Between 1906 and 1911, the year the Société Antoinette went bankrupt, that firm might have produced a few hundred engines used on aeroplanes, racing boats and automobiles as well several dozens of aeroplanes.

The first of the latter was the one and only Gastambide-Mengin monoplane, later renamed Antoinette II, designed by Levavasseur and tested in February 1908. That machine was followed by the Antoinette IV, V, VI and VII, a two-seat machine, collectively test flown in 1908-09.

Levavasseur’s last design was the revolutionary Antoinette Monobloc. Completed in the fall of 1911, the one and only example of that streamlined and futuristic machine proved too heavy to make more than brief hops. Its poor performance at the 1911 Concours militaire d’aviation, held near Reims, France, in October and November, proved to be the death knell of the Société Antoinette.

Mind you, in 1910, Société Antoinette also produced at least one example of what could well be the first flight simulator in the world, the tonneau Antoinette, in English the Antoinette barrel.

The large multi-wing aeroplane designed and built by Charles Groombridge and William Alfred South. Anon., “A New Aeroplane.” Scientific American, 10 October 1903, 262.

Charles Groombridge (1833-1917) and William Alfred South (1848-1907) were respectively an English technician / publisher / inventor and an English veterinarian / inventor who completed a large aeroplane with two sets of 5 wings mounted in tandem, as well as 6 propellers and, if my interpretation is correct, some sort of rotor on top. And yes, that flying machine was completed no later than October 1903, in London, England. It never flew.

Samuel Pierpont Langley. Anon., “Samuel Pierpont Langley, Ph.D., LL.D., D.C.L.” James Means, ed. The Aeronautical Annual, vol. 3, 1897. (Boston: W.B. Clarke & Co., 1897), inside front cover.

The Aerodrome designed by Samuel Pierpont Langley on its catapult, itself mounted on a houseboat moored on the Potomac River, near Washington, District of Columbia, 1903. Ferdinand Ferber, L’aviation, ses débuts, son développement : De crête à crête, de ville à ville, de continent à continent. (Paris: Berger-Levrault, 1908), 24.

Samuel Pierpont Langley (1834-1906) was an American amateur astronomer / amateur physicist / professor and Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution who designed an aeroplane with 2 pairs of wings mounted in tandem, the Langley Aerodrome, based on a pair of very successful steam-powered flying models, the Aerodromes No. 5 and No. 6 which, in May and November 1896, had covered increasingly impressive distances. The distance covered in November, for example, exceeded 1 525 metres (5 000 feet).

The design and construction work on the new aeroplane began in secret in 1898, in or near Washington, District of Columbia, thanks to a large sum of private money raised by Langley and a larger sum of money provided by the United States War Department, a subsidy born of a realisation on the part of some people within the United States Army that a piloted flying machine could be a useful observation platform. That realisation, in turn, came as a result of the onset of the Spanish-American War (April-August 1898).

Keeping the project secret proved difficult, however, especially when the large houseboat Langley planned to catapult his aeroplane from, an aeroplane known as the Langley Aerodrome, appeared on the waters of the Potomac River, near Washington.

The end result was endless gossip and a widely held view that Langley’s flying machine was a waste of government money which would never fly. Scientists that Langley knew more or less well shared that view.

In the fall of 1903, for example, a Canadian American astronomer / applied mathematician by the name of Simon Newcomb wrote a few articles whose conclusion was that, given the technology, materials and knowledge available in 1903, piloted powered heavier than air flying machines were not really feasible. That outlook might be altogether different in the future, however.

In any event, the Aerodrome was for all intent and purposes ready to fly in late August 1903, just a few days before a furious storm hit. The houseboat slipped its moorings and drifted downstream for 3 or so kilometres (2 or so miles) before its anchor caught in the bottom. The handful of men on board were happy to step ashore.

The Aerodrome might, I repeat might, have been on its catapult when the storm hit and seemingly suffered some damage.

It was worth noting that Langley’s Aerodrome was powered by a thoroughly redesigned version of an unsatisfactory gasoline engine ordered from a small American machine shop / automobile manufacturer, Balzer Motor Company. The gentleman responsible for that excellent redesign was a brilliant if eccentric American engineer, Charles Matthews Manly. If truth be told, the Balzer-Manly engine was far superior in power and power to weight ratio to the one used by the Wright brothers on 17 December 1903.

Oddly enough, the Aerodrome did not have a landing gear. All it had were a quintet of small floats designed to prevent it from sinking. And yes, the absence of a landing gear meant that any landing on land or water would have caused (considerable?) injury to the pilot and damage to the aeroplane.

Speaking (typing?) of damage, the engine of the Aerodrome failed to work properly during test runs in early September and had to be repaired. The following day, the portside / left side propeller of the aeroplane self-destructed during a test run. Had it not been for Manly’s quick action in shutting off the engine, the Aerodrome might have been ejected from its catapult.

Less than a week later, the portside propeller self-destructed yet again.

The first flight attempt of the Langley Aerodrome, Potomac River, near Washington, District of Columbia, 7 October 1903. F. de Rue (Louis Ferdinand Ferber), “Historique des expériences de Langley.” L’Aérophile, March 1906, 67.

Charles Matthews Manly, on the left, about to be rescued after the crash of the Langley Aerodrome in the Potomac River, near Washington, District of Columbia, 7 October 1903. F. de Rue (Louis Ferdinand Ferber), “Historique des expériences de Langley.” L’Aérophile, March 1906, 69.

The first flight attempt of the Aerodrome took place on 7 October 1903. Manly was at the controls and Langley was presumably in his office, in Washington. As the aeroplane ran down its catapult, one of its wings might have made contact with it. Now unbalanced, the Aerodrome fell in the Potomac River “like a handful of mortar,” if yours truly may quote a contemporary news report. Manly was unharmed.

Mind you, it looked as if the forward pair of wings of the Aerodrome warped slightly and pushed the aeroplane downward. Said wings, it seemed, lacked solidity.

The Aerodrome was soon fished out of the water and repaired.

The second flight attempt of the Langley Aerodrome, Potomac River, near Washington, District of Columbia, 8 December 1903. Smithsonian Institution, A-18853.

The second flight attempt of the Aerodrome took place on 8 December 1903. Manly was yet again at the controls. The wind was then somewhat gusty and the skies were darkening. As the aeroplane ran down its catapult, its tail bent sideways and its pair of rear wings folded up. Utterly unbalanced, the Aerodrome pitched upward, slowly flipped on its back and crashed in the cold waters of the Potomac River.

The small boats where Langley and a number of dignitaries had gathered the see the flight rushed to the site. After a few anxious moments, Manly came to the surface, unharmed yet again. He had been briefly trapped underwater. Indeed, one could argue he had been lucky to survive.

As was to be expected, Langley was the subject of a great deal of mockery. He was also blamed for wasting up to US $ 50 000 in tax payers’ money, a sum which corresponds to up to $ 2 350 000 in 2024 Canadian currency.

Stored in its damaged state in a building of the Smithsonian Institution, I think, Langley’s Aerodrome was all but forgotten until 1914 when the gentleman who had succeeded Langley as Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, the American paleontologist Charles Doolittle Walcott, and American aviation industrialist Glenn Hammond Curtiss got together to discuss items of mutual interest.

You see, in 1909, lawyers hired by Wilbur and Orville Wright had launched the first of a series of lawsuits against American and foreign aviators flying in powered aeroplanes on American soil. As far as the Wrights were concerned, the American flight control system patents they had meant that every aviator active in the United States had to pay them a licence fee.

I know, I know. The resulting patent war was really quite ridiculous. Worse still, it seriously hobbled the development of aviation in the United States until 1917 and the creation of a patent pool, approved by the government, seen as the only way to prevent the quarrel from hampering aeroplane production now that the country had entered the First World War, but back to the Langley Aerodrome.

A person with a negative turn of mind, not yours truly of course, might be tempted to state that Walcott and Curtiss launched a plot with multiple goals linked to their common desire to take away from the Wright brothers their pole position in the development of powered flight.

One of the goals close to Walcott’s heart was the rehabilitation of Langley and the Smithsonian Institution, not to mention his own. You see, he had been involved in the Aerodrome project from 1898 onward. Mind you, Walcott also hoped that highlighting the capabilities of the Aerodrome would help convince the American government to put the Smithsonian Institution in charge of the national aeronautics laboratory whose creation was being proposed at the time.

Curtiss’s goals were a tad more down to earth. No pun intended. He wanted to bypass / discredit the Wright brothers’ patents, thus improving the fortune of his firm, Curtiss Aeroplane Company, which was not doing great at the time, and even the score with the surviving brother, Orville Wright, the older one, Wilbur Wright, having died in May 1912, at age 45.

In any event, in May 1914, Curtiss announced that Curtiss Aeroplane would repair the Langley Aerodrome. A well known pilot mentioned in November 2018, September 2020 and October 2022 issues of our iridescent blog / bulletin / thingee, Lincoln J. Beachey, would then fly that aeroplane, thus proving that Langley’s Aerodrome was the first piloted powered aeroplane able to make a controlled and sustained flight.

What the staff of Curtiss Aeroplane did to the Aerodrome was more than simple repairs, however. That aeroplane was substantially modified, including at the level of its engine and 2 propellers. And yes, those modification were done in secret. Mind you, the Aerodrome was also fitted with floats.

In late May 1914, the Aerodrome 2.0 first lifted off from the waters of Keuka Lake, New York, near the site of the Curtiss Aeroplane factory, at Hammondsport, New York. Curtiss was in the pilot’s seat. Walcott was on hand to congratulate him. Curtiss flew again, twice and briefly, in early June.

Countless newspapers published articles about the flights and how they had vindicated poor old Langley, who had unjustly died of a broken heart, in February 1906, at age 71. The press, it seemed, had been rolled in flour by the wily Curtiss and Walcott.

One of the pilots employed by Curtiss Aeroplane piloted the aeroplane on at least 2 occasions in September 1914. On one occasion, William E. “Gink” Doherty covered a distance of 800 or metres (2 625 or so feet). Doherty or another American pilot, Walter Ellsworth Johnson, allegedly managed to cover a distance of 32 or so kilometres (20 or so miles) over Keuka Lake at some point in 1915, but only in a straight line. You see, the Aerodrome could not really make turn.

And no, the flights of the Aerodrome failed to undermine the patents held by Orville Wright.

Incidentally, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics came into being in March 1915. And no, the Smithsonian Institution was not given the responsibility to run that committee mentioned in November 2018, January 2020 and August 2020 issues of our interstellar blog / bulletin / thingee.

Secretly returned to its original 1903 configuration, the Aerodrome went on display at the Smithsonian Institution in 1918. Near it was a text panel which stated that it was the first piloted powered aeroplane capable of sustained flight. I kid you not.

And no, that was not the Smithsonian Institution’s finest hour.

Orville Wright was understandably incensed / indignant / outraged. His anger was such that he refused to donate or even loan the historic 1903 Wright Flyer to the Smithsonian Institution. Instead, Wright loaned that iconic machine to the Science Museum of London, England. The Flyer went on display there from March 1928 onward.

In October 1942, the Smithsonian Institution publicly retracted its claim that the Aerodrome was the first piloted powered aeroplane capable of sustained flight. Orville Wright had won his war.

The Wright Flyer went on display in the Smithsonian Institution in December 1948. Sadly, Orville Wright was not there to see it unveiled. He had died in January 1948, at the age of 77.

As we both know, less than 10 days after the crash of Langley’s Aerodrome, yes, 10 days, not 10 000 000 years, the Wright brothers managed to get into the air, on the windy site of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Orville Wright’s first flight covered a distance of 37 or so metres (120 or so feet). Wilbur Wright did a tad better, with a flight of 53 or so metres (175 or so feet). Orville Wright replaced him at the controls of the Wright Flyer and covered a distance of 61 or so metres (200 or so feet). One could argue that those flights were little more than hops. Indeed, the longest one had lasted but 15 or so seconds.

The flight which, in yours truly’s mind, really made history was the 4th and final flight made that day, the one performed by Wilbur Wright, the one during the Wright’s biplane covered a distance of 260 or so metres (852 or so feet) in 59 or so seconds, at an average speed of less than 16 kilometres/hour (less than 10 miles/hour).

If I may be permitted to paraphrase the title of an excellent British documentary television series, The Day the Universe Changed: A Personal View by James Burke, broadcasted between March and May 1985, 17 December 1903 was indeed a day the universe changed.

Over the following years and decades, the capabilities of our flying machines have improved by leaps and bounds. Sadly enough, their capabilities to spread death and destruction have followed the same path, a path to annihilation made possible by thermonuclear weapons.

And please do not get me started on air travel.

And that is it for today, my ever patient and somewhat surprised reading friend.

It goes without saying that our all too brief overview of the piloted powered heavier than air flying machines fabricated and / or tested before 17 December 1903 is undoubtedly not exhaustive. Indeed, any information leading to the addition of other names to our list would be most welcome.

Any person about to make a headlong rush toward a keyboard may wish to note that the New Zealander farmer / inventor Richard William Pearse (1877-1953) stated in 1909 that he had not done any actual work on an aeroplane before 1904. The 1902-04 flight or flights made near Waitohi, Aotearoa / New Zealand, associated with his name by people who came forward years, if not decades later, did not really happen.

The same must be said of the unsuccessful test flight allegedly made in 1901-02 near Rossland, British Columbia, by a mechanic, “Lou” Gagnon, perhaps born Frederick Odilon Gagnon (1864-?), in Drummondville, Canada East, today’s Québec, who worked in a gold mine located a sizeable distance away in British Columbia. The twin-engined steam-powered winged helicopter he assembled, a flying machine later known as the Flying Steam Shovel that people mentioned decades later, never actually existed, I think.

This writer wishes to thank the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, not theirs.

Carpe diem.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)