That was also one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind: The flight into space of Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin in the French language press of Québec, 12-15 April 1961, Part 2

Welcome aboard, my reading friend. I hope you will like this second part of our article on Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin’s space flight as seen in the French-speaking Québec press in April 1961.

Would you believe that the editorial writers of some major Québec dailies commented on the flight of the first Homo sapiens to travel in space? If you have no objection, let us start with the one which appeared in the 13 April issue of La Presse, a major daily in Montréal, Québec. The text written by a prominent journalist and columnist had a shocking headline, in translation: “Man’s dreadful victory. “

“Fabulous! Awesome! Fantastic!,” everyone exclaimed, pointed out Roger Champoux, in translation.

Russian science has just achieved the most overwhelming feat in the history of mankind and in front of the “worm” which inhabits planet Earth, a thousand new abysses are opening up that it will now have the audacity to explore given that a young man of 27, Yuri Gagarin, dared the incredible adventure and succeeded.

This being said (typed?),

[the] Russian triumph offers something insane because we are now entitled to dare everything, to launch into the abyss and to affirm, this time believing it, that nothing is impossible for man. […] Who can now claim that we will not get to know the Martians provided they exist.

Champoux then continued his remarks in another direction, again in translation: “A mystery surrounds the feat of Gagarin aboard the ‘Vostok,’ however.” Indeed, a rumour circulated from 9 April according to which the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) had launched a man into space. On 12 April, a spectacular ceremony in Moscow was canceled at the very last moment, stated Champoux. What was going on?

Some people wondered if, in fact, a first launch had not taken place [on 8 or 9 April], resulted in failure and that then Gagarin would have been the second human to offer his life on the altar of glory. He succeeded. The other... will we ever know… even his name?

Would you believe that this legend according to which Gagarin was not the first Homo sapiens to go to space is still making the rounds in the blogosphere in 2021? I am not joking. In April 1961, a British populist conservative daily, Daily Sketch, claimed that the Soviet cosmonaut in question, Gennady Mikhailov, did not survive the trip.

According to a recent non-Russian version of the legend, it was a certain Vladimir Sergeyevich Ilyushin who orbited the Earth 3 times on 7 April before crashing in China. This civilian test pilot survived the crash but was seriously injured. Ilyushin not being presentable to the Soviet public, assuming that the Chinese government agreed to return him home in time, someone suggested placing in front of the cameras the very photogenic Gagarin, who may very well never have set foot in space. The mind boggles.

Many Homo sapiens believe in some very strange things, from the flatness of the Earth to the presence of intelligent life on that planet, but back to our editorial.

And you have a question, don’t you, my reading friend? Let me guess. Are Mikhailov and Ilyushin fictional characters? If Ilyushin was a very real excellent test pilot, the fact is Mikhailov never existed. Now back to our editorial.

The political prestige and scientific advance acquired by the USSR following Gagarin’s flight were immense, to say the least, Champoux argued. The United States proved to be good losers, and researchers around the world had to humbly beg their Soviet colleagues to give them access to their information. In Champoux’s words, in translation, “[science] has become too gigantic a power to serve only a nation. Sharing is our only safeguard.“

Since the discovery of fire, the earthling believed he had everything. Now he is violating the secret of space, heading probably towards the sun, dares to disturb “the eternal silence of these infinite spaces” which so terrified [the French theologian, physicist, philosopher, moralist, mathematician and inventor Blaise] Pascal… and all this to own what?

Peace? Happiness? The answer, this time again, rests only with God.

The 13 April issue of La Presse also contained the first of a series of 4 articles written by (scientific?) journalist Roland Prévost and entitled “Dans le sillage de Gagarine:”

- 13 April - “Que trouvera l’homme dans l’espace?“

- 14 April - “Sur les routes célestes, cailloux et poussière”

- 17 April - “Obstacle : rayons invisibles”

- 18 April - “Pourquoi risquer des fortunes et des humains dans l’exploration spatiale”

Also on 13 April, the editorialist of Le Soleil, the main daily in Québec, Québec, in a text entitled “Un homme dans l’espace,” demonstrated real sobriety. “The Russians have just recorded another scientific success,” he said at the outset, in translation. No more. “That this feat could have happened indicates to what an incredible degree of development science is now at.” A slightly impertinent comment if I may. The success of Gagarin’s journey may owe more to technology than to science, but let’s move on.

“For the Soviet Union,” the editorialist continued, “this is both a scientific [sic] and psychological success. […] The Russians get a new halo of scientific glory by sending their first man into space.” Better yet, some are talking about launching a probe to Venus.

From a psychological point of view, it is obvious that the Soviet people feel great national pride in seeing their country thus lead the world in space research; the regime is all the more strengthened internally and sees its prestige increase outside its borders. This is certainly one aspect of the question that the leaders of the USSR do not forget to consider.

The editorialist of Le Soleil ended his editorial on a somewhat lyrical note: “It is literally a new world, a new America, coming before us. How much will this knowledge transform our traditional concepts, what effects will it have on humanity? “

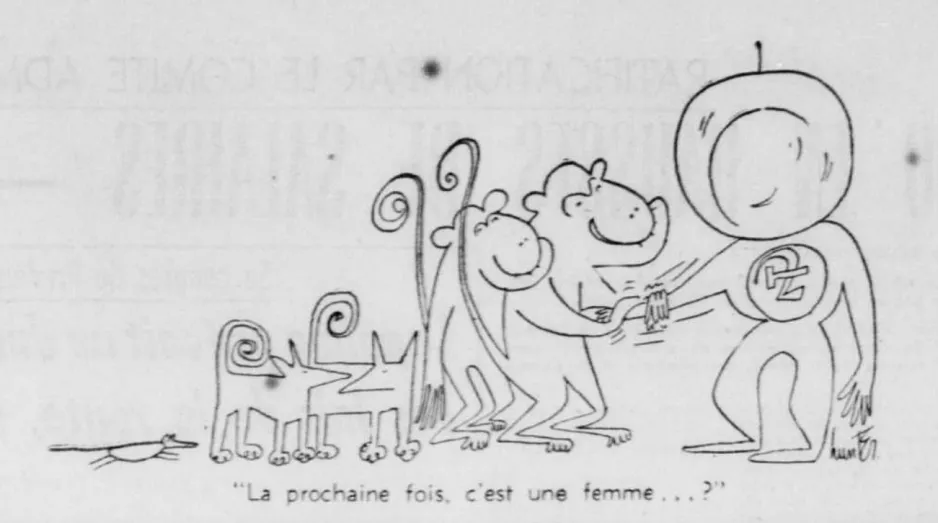

An editorial cartoon by Raoul Hunter, one of the most famous and respected Québec / Canadian cartoonists of his time and a gentleman mentioned in an October 2020 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, can be found on the same page as the editorial discussed in the previous paragraphs.

Raoul Hunter, “–.” Le Soleil, 13 April 1961, 4.

I have to admit that the caption of the drawing, in translation, “Next time it’s a woman…,” leaves me a little / a lot uncomfortable.

If I may, the very subject of a drawing in the series “Drôle de jour,” by Berthio, whose real name was Roland Berthiaume, a well-known Québec cartoonist, published in the 15 April issues of La Presse also leaves me a little / a lot uncomfortable. I mean, the first woman in space?

Berthio, “Drôle de jour.” La Presse, 15 April 1961, 2.

In La Tribune, the French-language daily in Sherbrooke, Québec, the homecity of yours truly, the editorial of 13 April used a title which was certainly original, if somewhat inaccurate: “Le baron de Münchhausen n’est plus un mythe.” And no, said baron was not a fictional character. Nay. Baron Karl Friedrich Hieronymus von Münchhausen was born in May 1720, in a territory that is now part of Germany.

This cavalryman related his adventures, each more extraordinary than the last, to a polymath born in the same territory which is now part of Germany. Riddled with debt and on the run for selling objects from the cabinet of curiosities and medals of a prince reigning in a territory that is now part of Germany, a cabinet of which he was the curator (!), Rudolf Erich Raspe published anonymously, in 1785, a novel inspired in part by von Münchhausen’s stories, Baron Munchausen’s Narrative of his Marvelous Travels and Campaigns in Russia.

Von Münchhausen was very unhappy to see his life thus placed in the public square, but the fact was / is that the book became very popular (8 editions between 1785 and 1799!) – a popularity that cannot be denied in 2021.

Unfortunately, Von Münchhausen did not make a penny from the success of the many editions in English, French, German, Russian, etc. of his crazy adventures. He died ruined in February 1797, at the age of 76. Raspe, for his part, died in November 1794, at the age of 58, without having benefited from the international success of his work.

Eager to stress that “the achievement of the Soviet Union leaves no one indifferent,” the La Tribune editorialist began his remarks forcefully: “This is the event of the century, some said; this is the breaking of the universe, affirmed others, it is the logical outcome of the launching of the first artificial satellite, some concluded.” In fact, affirmed this same editorialist, the world had awaited the launch of a being human in space for several months.

While Gagarin’s flight “no longer surprises anyone,” its consequences were no less profound. “The notions learned about the sidereal universe are slowly falling apart. The very conception of man is changing.” Mankind, the columnist emphasised, was no longer entirely a prisoner of the Earth. “Undoubtedly, space travel for the mass of the population is not yet for tomorrow, but what has been accomplished so far points to even more astonishing developments.”

An interesting detail, if only for yours truly, La Tribune published 2 photographs of important people in the world of astronautics and aeronautics. And yes, my reading friend, it is indeed these photographs which are at the beginning of this second part of our article on Gagarin.

Gagarin and the first secretary of the central committee of the Kommunisticheskaya Partiya Sovetskogo Soyuza, Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev, Vnukovo international airport. Anon., “Défi pacifique de ‘K’ aux États-Unis – Moscou fait un triomphal accueil à Gagarine.” La Presse, 14 April 1961, last edition, 24.

Having published an editorial on Gagarin’s flight on 13 April the management of La Presse did not believe it necessary to publish a second. The last edition of the 14 April of the Montréal daily, however, offers its readers a photograph showing Gagarin with the first secretary of the central committee of the Kommunisticheskaya Partiya Sovetskogo Soyuza, that is the Communist Party of the USSR, Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev. This character was keen to be clearly visible during the celebrations surrounding the triumphal arrival in Moscow of the cosmonaut on 14 April.

In fact, Mr. K, as Khrushchev was often called, was present at Vnukovo international airport, where the Ilyushin Il-18 airliner of Aeroflot, the Soviet air carrier, which was carrying Gagarin, landed.

And yes, this type of airliner, one of the most successful Soviet airliners if you have to know, was designed by the experimental design office led by Sergei Vladimirovich Ilyushin, one of the great aircraft designers of the 20th century and daddy of the aforementioned Ilyushin.

Would you believe that the lace of Gagarin’s right shoe was undone as he walked, very seriously, as if butter would not melt in his mouth, towards the podium where a Khrushchev overflowing with joy and pride awaited him? Would you believe that said lace apparently remained clearly visible when the cosmonaut’s arrival was broadcasted, on television and / or in cinemas in the USSR, a country where even the blades of grass in official photos had to be well aligned, brushed and cut? The presence of said lace humanised Gagarin and it was apparently for this reason that the Soviet propaganda experts decided not to make it disappear.

If I may be permitted a comment, Gagarin apparently knew very well that his lace was undone and he very much hoped, dare I say that he implored the heavens, not to get tripped by said lace, in front of Khrushchev and other senior members of the Kommunisticheskaya Partiya Sovetskogo Soyuza, in front of his wife, children and parents, and in front of the huge enthusiastic crowd and the Soviet and foreign photographers and cameramen who were at the airport.

Mind you, the last edition of the 14 April issue of La Presse also features an untitled drawing by illustrator and cartoonist Pierre Dorion. Said drawing accompanied an international press review on the “victory of human intelligence” which was the flight of Gagarin

A drawing suggesting Gagarin’s journey around the Earth. Paul Dorion, “Une victoire de l’intelligence humaine.” La Presse, 14 April 1961, 4.

Now let us see what Le Soleil had to say about Gagarin that same 14 April. First, it should be noted that it published a wider version of the photo showing Gagarin and Khrushchev.

This issue also included an article entitled “L’art et le cosmos.” Its author, the Québec painter Claude Picher, was ex-director of exhibitions (1951-58) at the Musée de la province du Québec, today’s Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, in Québec, the city of course, and representative (1958-1961) at the National Gallery of Canada, in Ottawa, Ontario.

The style of said text might be a bit surprising, both in French and in translation.

The launch of the first man into space arouses various reactions: the scientist exults, the onlooker is amazed, the imbecile, after an ah! of astonishment, continues as yesterday to sell his pickles, the philosopher is worried, the artist wonders if his painting, his novel or his oboe sonata will still touch the man who saw the Earth from so far away and who is about to land on the Moon!

If I may be permitted a slightly impertinent comment, in 1961, and in 2021 for that matter, it was / is in a small part the taxes paid by imbeciles who sold / sell pickles, in other words members of the working class, like my parents, who paid / pay the salaries and pensions of museum employees. Anyway, let’s move on – and back to Gagarin’s flight.

This is an extraordinary feat and also an extraordinarily unnecessary one. The day is not far off when man and a whole menagerie will endlessly circle the globe, a turtle, snake or elephant poop reminding us from time to time of their presence, like a postcard.

Will this new dimension add something to man, will it make him feel his pettiness, will it make him ashamed of his small intellectual baggage, will it instill in him a desire to surpass himself? We can doubt it. The achievement of this man and the degree of science it assumes are already written in a class book ready to be memorised, such as the date of the invention of gunpowder. No later than today, the same gossip is muddling the phone lines, profiteers are dumping their bad wares, and preparations for war continue. A man saw the world as a whole and we still wonder if we should admit China!

By the way, it was not until October 1971 that China became a member of the United Nations Organization, after 20 unsuccessful votes between 1949 and that date. The United States played a crucial role in these repeated failures.

Interestingly, in a paragraph where he wondered where art was going to stand given the “dizzying and unnerving progress of science,” Picher offered the following words: “Will sculptors announce statues made in clay from the Sea of Tranquility?” Why is that interesting, you ask, my reading friend? Why?! Imbecile pickle seller! Sorry, sorry.

This being said (typed?), don’t you know that it was in Mare Tranquillitatis that 2 American gentlemen mentioned several times in our you know what since June 2019, Neil Alden Armstrong and Edwin Eugene “Buzz” Aldrin, Junior, treaded this lunar soil where the hand of man had never set foot, in July 1969? But back to Picher’s text.

The more science goes forward, the more the idea of progress in art, of its liberation from themes of old human background, becomes ridiculous, unthinkable!

Gagarin having traveled into space, many predictions of science fiction works published since the 19th century were partly fulfilled, if not partly outdated. We will no longer be able to read them as before, their poetry having disappeared.

This being said (typed?), all was not lost, Picher believed.

Imagined in every imaginable world, experienced in rocket metal, the natural functions of men, love and others, will not change, however, and will continue to inspire the great works of the mind. In that sense, every time a human is happy or crying, it is newer and more important than the fastest alien travel.

From great prehistoric works to [Vincent van] Gogh, from Madame Bovary to the Condition humaine, from [Ludwig von] Beethoven to [Modest Petrovich] Moussorgsky, there has been no progress in emotion and this magnificent absence of progress is perhaps the greatest originality of art. So will always amaze me, before they bother me for good, these boring musicians sticking soundtracks end to end, overlaying them, cutting them up; these painters spitting on their canvases, spatulating for no reason, making buttons with cake molds, seeking inspiration by looking at hairs under a microscope and believing to live the cosmic adventure of Yuri Gagarin, while the novelty, the cosmos for the artist are contained in this man who turns the corner of a street with his hidden emotions.

The 14 April issue of the daily Le Progrès du Saguenay, in Chicoutimi, Québec, contained an editorial titled “Exploit merveilleux, mais inquiétant.” If J.G. (Jean Guy?) Lamontagne readily acknowledged, in translation, that “[all] the universe [sic] bows before the exploit which Russia has just accomplished,” the fact was that “[this] marvelous exploit illustrates more than any other the power of man to whom God himself granted the power to dominate matter and conquer spaces, in order to assert himself the true king of creation.”

This being said (typed?), Lamontagne did not hide his concern. “Let us do our act of humility. Democracies have just received a terrible shock. It is no coincidence that Russia, the dictatorship of dictatorships, outdid all countries deemed to be free.” The Soviet government being in fact absolute master in matters of economy, education, research and of application of said works, of human lives itself, in the USSR, its superiority in the conquest of space is undeniable.

“This same superiority, Russia will be able to resort to, at any moment and without prior notice, the day it wants to turn against us the forces of destruction which it knows how to dominate and exploit better than any other nation.”

Two brief comments if I may.

One. As despotic as the USSR was in 1961, it was not the USSR under Josif Vissarionovitch “Koba” Stalin, born Ioseb Jughashvili. It was not National Socialist Germany under Adolf Hitler either.

Two. Unless I am mistaken, the USSR and United States had about 10 and 57 intercontinental ballistic missiles, respectively, in 1961, a ratio of 1 to 5.7. The United States’ (thermo)nuclear arsenal exceeded a little bit that of the USSR in 1961: around 2 470 (thermo) nuclear weapons for the latter and around 22 230 for the United States. United, a ratio of 1 to 9. With respect, of the 2 superpowers, which one knew how to dominate and exploit the forces of destruction better than any other nation? Anyway, let us move on.

Lamontagne forged ahead by pointing out that, even if no head of government pushed The Button,

a simple miscalculation could cause the worst disaster. God has granted man the power to build and destroy, to the point of destroying himself and the entire universe that he inhabits.

Let us pay homage to the Creator of the victories won by the human genius of which he is the author, and let us ask him to guide the brain and hand of man so that the forces at his disposal never turn against him.

And no, I do not believe that humans can destroy the universe. At least not yet.

The 14 April issue of L’Action catholique, a daily in Québec, the city of course, also contained an editorial. There was also a block of 3 photographs, a “Synthèse d’un exploit scientifique.”

Gagarin, an American map showing his route and a sectional view of his space capsule. Anon., “Synthèse d’un exploit scientifique – Nikita Khrouchtchev embrasse Yuri Gagarin [sic].” L’Action catholique, 14 April 1961, 1.

And yes, my eagle-eyed reading friend, the space capsule visible in the photograph above had nothing to do with the one that flew into space in April 1961. It was indeed a cutaway view of an American McDonnell Mercury space capsule, but back to the editorial in L’Action catholique.

Frankly, I wonder if this is really an editorial. The text in question, very positive it should be noted, was nevertheless on page 4, with an editorial by Louis-Philippe Roy, a doctor who became a journalist for the love of this profession. Also written by Roy, it is entitled “Glanures – Un homme dans l’espace” – a mini editorial perhaps?

One should rejoice about this experience because, like so many others, it testifies to the intellectual capacity of man, a creature of God to whom we must ultimately pay homage.

Moreover, if science can accomplish such great feats it is because there is an order in nature, it is that the stars obey laws set by the Creator and accessible to the human mind.

It remained to be seen why the USSR managed to outdo the United States.

It is because in Soviet Russia, scientists are no longer free, they are conscripted and well paid. So instead of seeing a necessarily limited team of volunteers devoting themselves to such or such particular research, all the scientists of the country are mobilised for the same cause. All other things being equal, the odds are obviously on the side of the numbers in this area.

The main thing is that this new conquest turns in favor of bringing peoples together, in favour of peace, to the glory of God.

While the 14 April issue of the newspaper Le Nouvelliste in Trois-Rivières, Québec, did not contain an editorial, it did contain a large photograph of Gagarin.

Gagarin shortly after his return to Earth. Anon., “De retour de l’espace – Gagarine raconte son voyage.” Le Nouvelliste, 14 April 1961, 1.

The 15 April issue of Le Soleil, on the other hand, featured, on its penultimate page, a photograph of a tiny part of the huge, delirious crowd that flocked to Red Square in Moscow to cheer Gagarin. Said square had not received such a multitude since the defeat of National Socialist Germany in May 1945. This issue of the Québec daily also contained a poor quality photograph of Gagarin kissing his wife shortly after his arrival at Vnukovo international airport.

Muscovites among many who celebrated Gagarin’s robbery. Anon., “La Russie accueille le premier voyageur de l’espace au monde.” Le Soleil, 15 April 1961, 49.

Gagarin kissing his wife, Vnukovo international airport. Anon., “La Russie accueille le premier voyageur de l’espace au monde.” Le Soleil, 15 April 1961, 49.

The rapid disappearance of Gagarin’s historic journey from the front pages of major Québec dailies may come as a surprise, given the extent of the coverage these same newspapers had given to the launch of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik I.

This being said (typed?), the editors of these publications had to take into account what was happening in Québec and elsewhere.

Let us mention, for example, the prosecution on 10 April of Tomasz Biernacki, a brilliant Polish engineer specialising in hydroelectricity on internship at Surveyer, Nenniger and Chênevert Incorporée in Montréal. The head of the mechanical engineering department of this engineering firm mentioned in a December 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee was accused of spying on behalf of an unidentified country. Released on bail in May, he was re-arrested just moments later. Biernacki was released on bail a second time, in June.

A well-known Montréal criminal lawyer brilliantly defended him. In January 1962, a bolt out of the blue, the judge responded to Joseph Cohen’s request to dismiss his client’s privileged indictment, an approach used by the crown to skip the preliminary investigation stage. Biernacki was released without going to trial. Informed by a representative of the federal government that it believed him guilty, regardless of the judge’s decision, the Polish engineer returned to Poland even before the end of the month.

A brief, actually not that much, digression if I may. Approached in 1958-59 by the Polish internal and external security service, the Służba Bezpieczeństwa (SB), Biernacki agreed, in the weeks preceding his arrival in Montréal, to acquire information of a scientific and technical nature on subjects unknown to this writer, as well as personal information about the Polish community in Canada. He obviously left alone, his wife and children remaining in Poland to ensure his loyalty.

When questioned after his arrest by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), which had obviously searched his home, Biernacki wasted no time in confessing. In fact, he revealed (all?) the details of his activities. Better yet, Biernacki revealed the location and time of an upcoming meeting with an SB representative in Canada. The latter, a professional spy if ever there was one, escaped the ambush set by the RCMP. Well aware that Biernacki, an amateur spy if there was one, had spilled the beans, the Polish government nevertheless decided to defray the costs of his defence.

Interestingly, Biernacki may have been one of the spies and moles exposed by the Polish military intelligence agent Michał Goloniewski, whom the Central Intelligence Agency had smuggled into West Germany in January 1961.

The failure of Biernacki’s espionage mission, described in great detail by the latter during his debriefing in Poland, did not appear to be detrimental to his career. Professor at the Politechnika Gdańska from around 1965, he held the post of rector of this polytechnic school between 1975 and 1978. Biernacki was also undersecretary of state at the ministry of Science, Higher Education and Technology between 1978 and 1981. He died in May 1989, at the age of 65, but I digress.

Another event hit the headlines in April 1961. Indeed, who could forget the start of the trial of one of the architects of the Holocaust, Otto Adolf Eichmann, on 11 April, in Israel? Found guilty, this all too ordinary monster was executed in May 1962.

Let us not forget either the debate surrounding the stranglehold of the Roman catholic church on the education system of Québec, a stranglehold denounced by more and more people, after the defeat of the party long led by the (too?) conservative Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis, a character mentioned in several / many issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since January 2018, and the coming to power of the stupendous team led by Jean Lesage, a gentleman mentioned in several / many issues of this same publication since July 2018, during the general elections of June 1960.

One only needs to think of a very scathing work published anonymously in September 1960 by Brother Pierre-Jérôme, a brother teacher, scholar, go-getter and good storyteller born Jean-Paul Desbiens. At a time when a book selling 10 000 copies was a bestseller, Les insolences du Frère Untel, in English The Impertinences of Brother Anonymous, sold over 100 000 copies. Desbiens denounced the archaic education system in Québec as well as the fear-based Catholicism practiced in the province. The Québec Catholic hierarchy burned with rage. Mind you, the Surintendant de l’Instruction publique, Omer Jules Desaulniers, for whom the education system of Québec was the best in the world, was probably not happy either.

Identified shortly after the publication of his book, Desbiens was sent, dare I say exiled, to Rome, in 1961, where he was placed under close surveillance. He undertook a doctorate in Switzerland in September 1962, again under close surveillance, but returned to Québec in 1964. The very first minister of Education of Québec, Paul Gérin-Lajoie, made Desbiens one of his principal advisers, and…

Let me guess, my reading friend, you have a question. How is it that, before the 1960s, Québec did not have a ministry of education? A good question. While a Département de l’Instruction publique had been operating since 1875, it was above all a management body which reported to the Secrétariat de la province de Québec, a sort of Interior ministry with fingers in many pies.

Before the creation of the Ministère de l’Éducation, in 1964, the real decisions concerning the education of the vast majority of the population of Québec, the catholic population, were in fact taken during the meetings of the Comité catholique of the Conseil de l’instruction publique, an organisation whose members, obviously not elected, were the very conservative catholic bishops of Québec and an equal number of lay people who were not known for their liberalism either, but back to our story.

An event with even more serious consequences occupied the front pages of Québec dailies from mid-April: an invasion of Cuba or, more precisely, an air attack, on 15 April and a landing on the 17th, launched by Cuban exiles supported by the administration headed by president John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Said invasion, known as the Bay of Pigs Invasion (Invasión de bahía de Cochinos), turned out to be a total failure. Denounced by many countries around the world, it seriously embarrassed both the American president and the United States.

As positive as Kennedy’s memory may be in 2021, the fact is that he was indeed a Cold War president. He was not particularly interested in the exploration of space. His promise to make a trip to the moon before the end of the 1960s was not meant to be a giant leap for mankind. He simply wanted to add to the prestige of the United States and diminish the prestige of the USSR.

Have a good week, my reading friend, and do not forget to keep your feet on the ground.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)