View from above: Capturing the experience of flight on film

As a filmmaker, Les Harris has made numerous captivating documentary films and television series on aviation topics. He started his career as an independent filmmaker in 1970, and is well known for his docu-series on early aviator Charles Chabot. In 2017, Harris generously donated his aviation-themed archives to the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa.

In honour of the World Day for Audiovisual Heritage (October 27) — dedicated to raising awareness of the unique ways audiovisual recordings capture events, and the challenges memory institutions confront when trying to preserve such recordings — the Ingenium Channel caught up with Harris to discuss his innovative film-making techniques and the importance of preservation.

Ingenium Channel (IC): Les, what have been some of your favourite strategies in trying to capture the experience of flight on film?

Les Harris (LH): To start with, you must remember that at the time I was producing most of my aviation documentaries it was before 2000, and computer graphics were very basic and also extremely expensive then, so we couldn’t use that technology. So one had to think creatively.

In those days, the 16 mm cameras we used — like the Arriflex BL — were heavy (almost 8 kg) and bulky due to the 400 ft film magazine that sat on top of the camera. Added to that weight was a battery belt (10 kg) which the cameraman wore around his waist, along with a big power cord that attached to the camera. So it was impossible to manoeuvre the camera easily; and of course there was no room for a director, a cameraman, and a pilot in the early aircraft.

The solution I came up with was to use a smaller Beaulieu R16 Automatic 16 mm camera, which I learnt to operate myself. Although still heavy, it was possible to hold the Beaulieu with one hand — so you could do a small pan or small move. Also, being the director/editor, I knew exactly the shots I’d need to make the sequence work.

~ Les Harris

For Les Harris, the Beaulieu Automatic 16mm camera was a smaller and lighter option, which was conducive to small pans or movement.

IC: Your first project as an independent filmmaker was a series of films on Charles Chabot, who was the oldest living pilot when you started to interview and film him in 1970. In the title sequence to your Chabot Solo films, you seem to have filmed the 82 year old taking off in a reproduction of a Blériot XI. That seems a little irresponsible! Did he still have his license? How far did he fly?

LH: That brings back some memories for sure! Firstly, the Blériot XI was NOT a replica; it was one of only two still flyable Blériot’s in the world! I had been instructed by the owner that I could start its Anzani engine as long as the Blériot was tied down, and I could push the aircraft — but only with the engine off!

Chabot himself no longer had his license due to his age, and I could never have obtained accident insurance for him to fly it — as it [the aircraft] was priceless, being totally original. So we did a couple of shots of starting the engine (by priming it with gas, then swinging the propeller down), close ups of Chabot’s hand on the throttle, and pumping the oil for oil pressure. Then we did shots of his hands moving the yoke — which was like a joystick, and we shot the wires from the yoke bending the wings, which helped a Blériot turn and kept it in level flight. Add to that shots of his feet on the “rudder” pedals and finally, some shots of the wheels moving and the aircraft passing through the frame, along with close ups of Chabot’s head looking left, right, and ahead.

With that in the can, I found a pilot with a two-seater Tiger Moth to take me and the 16 mm Beaulieu up in his plane. By leaning over the side, I was able to film the ground disappearing away, clouds above, and even landing in a harvested cornfield — which I was able to use in another sequence of the film by printing it in black and white. So to answer your question, no Chabot did not even fly the Blériot one metre, but in Chabot Solo Part 3 he really did fly the Concorde at Mach 2.3!

Chabot Solo: Part 1, title sequence excerpt. Canada Aviation and Space Museum Archives. Les Harris Fonds. Copyright Les Harris. Music: Airman! Airman! (Don’t put the wind up me)” by Jack Payne and the BBC Dance Orchestra.

Transcript

| Audio | Visual |

|---|---|

| [Song begins to play. It is “Airman! Airman! (Don’t put the wind up me)” by Jack Payne and the BBC Dance Orchestra, first copyrighted in 1930. It is a comic song about an airman flying around a town, knocking people’s aerials down. It continues throughout the clip.] |

The main wheels of a Blériot XI pioneer aircraft is visible. They start rolling on the grass, moving from right to the left. |

|

A shot across the wing of the Blériot XI aircraft with the linen-covered wing blocking most of the shot. Only the top of the pilot’s head is visible at first. He is wearing a leather pilot’s cap. The airplane moves forward to briefly show past the wing, getting a glimpse of the pilot’s back. He is wearing a black jacket. |

|

|

|

The wheels of the Blériot XI roll forward on the grass. |

|

|

The wing is shown again and the ribs and structure are clearly visible. The wing moves to the left through the shot. |

|

|

The next shot shows the main wheels again, rolling to the left out of the shot. A few seconds later, the back wheel, a smaller single wheel, is visible as well as some of the tail of the aircraft. |

|

|

The pilot’s face is shown. He is an elderly white man with a white moustache and wire-rimmed glasses. |

|

|

The pilot’s body is shown in the open seat of the Blériot. His lower body is not sheltered by any part of the aircraft. He is wearing khaki pants and his legs are bent. The camera shakes. |

|

|

One of the main wheels of the Blériot rises from off the grass. |

|

|

The pilot is shown from the right over the wing. He pulls down on a lever. In the distance the blue sky and horizon is visible. The horizon tilts down and to the left. |

|

The shot shows the pilot from the front before dipping down into the engine. |

|

|

|

The ground is shown rushing by and then, after take-off, the sky and the tops of trees are visible. |

|

A shot shows the pilot from below, steering. |

|

|

|

The wings are shown from below. |

|

|

The pilot is shown from below and to the side. His shin is resting against part of the wooden fuselage. He continues to steer. |

|

|

The tip of one wing is shown against the blue sky. |

|

[Sound of engine sputtering.] |

The fuel tank is shown. |

|

[Sound of engine sputtering continues.] |

The pilot is shown from below. He looks down in the direction of the fuel tank. |

|

[Sound of engine sputtering continues.] |

Several thatch-covered buildings are shown from above and the shot descends quickly as if a crash is imminent. |

|

|

A title end card appears with the following information:

Extrait de la séquence d’ouverture de Chabot Solo, première partie. |

IC: So through a number of cinematographic tricks, you captured the experience of a take-off without actually sending an octogenarian up in a rickety pioneer aircraft! What other tricks have you learned, for example, when trying to film in an aircraft in flight?

LH: For interior shots, you need to use wide-angle lenses. These give you a wide view and are physically very small and light lenses, unlike zoom lenses or telephoto lenses which stuck out a lot in those days. Once Betacam SP videocassette cameras came out and you could start shooting on video, then it was possible to rent very small cameras that were the size and shape of a small cigar. They had a small cable that ran from them that supplied them with both power and transmitted the signal back to the Betacam SP camera/recorder. Today, I’d use a GOPro Camera as you can just tape them anywhere on the plane’s body; their quality is 4K and they record on a SD card.

Les Harris and a cameraman trying to get the right camera angle for a close-up of Charles Chabot in the Blériot XI.

IC: For this article, I wanted to broach the subject of aviation in fictional films. I had planned to ask you to break down a sequence from the film Wings (1927), which was named Best Picture by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and is still renowned in aviation circles for the realism of its air-combat sequences. I thought it would be in the public domain, but the versions of Wings that exist today were all extensively restored and remastered, creating — it seems — new intellectual property or a new copyright term at the issue of each version. Can you comment about your own past experience with the fragility of film and your point of view on its preservation needs?

LH: Nearly all the early motion picture film used was 35 mm. The early film, unlike film used later, was made using nitrate, which is highly flammable. I remember well one batch of old Pathe 35 mm film I needed to make a 16 mm copy from (an internegative). Only one lab in the UK was licensed to work with nitrate film, due to the fire risk. The lab film printer machine was massive, due to the thick steel all around it. After the film had entered the light proof printer — where it was copied onto the 16mm negative for me — it exited the printing area onto a large 35 mm spool called a “take up” film reel.

As the film started to wind up, it literally disintegrated into what I would describe as powder flakes. Luckily, my 16 mm neg was fine as this happened about two feet after the printer head. So this particular sequence of old Maurice Farnham and other 1914 era aircraft now only exists on Chabot Solo Part 1.

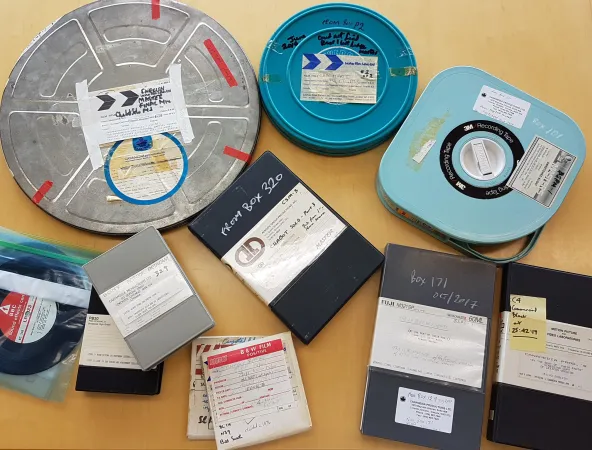

Unfortunately, film disintegrates over time, but the time can be extended to over 100 years if the film is kept in metal or plastic cans that don’t allow light in, and if it’s stored in temperature/humidity controlled vaults. Today, wherever possible, museums are also digitizing old films. But even then, the hard drives or discs used need to be copied to stop them deteriorating.

IC: Thank you, Les, for sharing your thoughts on aviation, film, and preservation challenges for World Day for Audiovisual Heritage!

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)