3 things you should know about tech-enabled cows, meteors, and presbyopia

Meet Renée-Claude Goulet, Cassandra Marion, and Michelle Campbell Mekarski.

They are Ingenium’s science advisors, providing expert scientific advice on key subjects relating to the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum, the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, and the Canada Science and Technology Museum.

In this colourful monthly blog series, Ingenium’s science advisors offer up quirky nuggets related to their areas of expertise. For the January edition, they explain new technology which is making cow births safer, an international citizen science initiative for monitoring meteors, and how a new eye drop is improving vision for the middle-aged consumer.

This calving sensor attaches directly to the cow’s tail, to detect its movements and the onset of active labour.

Tech-enabled cows are texting their midwives

It’s no secret that raising cattle is tough work, but "cow midwife" is probably not what comes to mind when imagining a dairy or beef farmer's job. In fact, tending to cow pregnancies and deliveries makes up a large part of the regular tasks on the farm. Now, a snazzy, tail-mounted device can help make that part of the job easier: by alerting the farmer when a calf is arriving, and potentially saving lives.

On beef farms, new calves are born regularly or seasonally; while in dairy, there is a constant flow of births year-round, ensuring the herd’s milk production stays stable. Birth is a very vulnerable time for the animals involved, so it’s wise for farmers to provide before and after care.

Generally, a cow will deliver her calf without any complications; farmers can stand back to let them do their thing. Post-delivery, the farmer needs to ensure the newborn is breathing and safe, and that it can get up, finds the mother’s teats, and drink colostrum. The farmer may also need to top up the birthing mother’s food and fluids, and give her any supplements needed — such as calcium.

However, just like in humans, a whole range of issues can complicate the birth process. Sometimes farmers have to intervene and readjust a calf’s position so it can safely come out, or help dislodge a larger calf, which may get stuck in the birth canal. This care can mean the difference between life or death for both animals.

Aside from knowing when she got pregnant (cows have a nine-month pregnancy) and monitoring physical symptoms closely, it’s difficult to know exactly when a cow will go into labour. Sometimes, birth happens without much warning — while farmers and employees are tending to other tasks — or in the middle of the night, when no one is around.

Enter the Moocall calving sensor, which provides an elegant solution for busy farmers. Mounted to the tail, it gathers 600 data points per second to detect and analyze tail movement. When the tail starts moving in the typical patterns that signal labour, the sensor device uses a Wi-Fi network to send a text message to the farmer’s cell phone and triggers an app notification. This happens an hour or so before the cow starts active labour, giving farmers plenty of notice to go tend to Bessie. Though this sensor is new to the market, it shows promise for enabling farmers to increase animal welfare and reduce calf and cow mortality or injury during and after birth.

Creative use of fairly basic technology is helping solve real — though sometimes not obvious — problems across industries, and this farm tech is a good example of that. Though cost of wide-scale adoption remains a barrier, the digital revolution hasn’t left farmers behind. In the coming years, we are sure to see more innovations like this, allowing farmers to optimize productivity, environmental sustainability, and animal welfare on their farms.

By: Renée-Claude Goulet

A full night of stacked images of 929 meteors detected during the peak of the Geminids meteor shower on December 14, 2021, collected from a Global Meteor Network camera in Spain.

Citizen scientists watch for fireballs in the sky

A global initiative to install highly sensitive, meteor-detecting video cameras around the world is taking shape. The Global Meteor Network (GMN), an international citizen science initiative, aims to monitor and collect meteor observations worldwide, in order to capture all rare meteor outbursts and meteorite-dropping fireballs, in addition to the well-known meteor showers like that of the Geminids last month.

Meteors are space rocks that enter the Earth’s atmosphere at high speed, then heat up due to compression and friction with the air. In the process, they display a brief but bright streak of light across the sky — hence the term “fireball” or “shooting star.” Larger rocks may survive the fireball stage, and drop to the ground and become a meteorite, or multiple meteorites, as they often break into multiple fragments.

Meteors can only be observed locally as they occur just 100 km above the Earth, and can only be seen from about 300 km away. Although the Earth is bombarded with meteors daily, very few of these have been monitored well enough to determine their orbit (where they came from in the solar system) and their trajectory (the flight path the meteor takes upon entry), which is used to predict where to go looking for meteorites on the ground. Observations by at least two cameras in different locations are needed to obtain this information; the more cameras, the more precise the measurement.

The GMN initiative is led and coordinated by Dr. Denis Vida, a meteor physics post-doctoral researcher at Western University in London, Ontario. Since 2017, Denis and his colleagues have grown their camera network to include 550 meteor-detecting video cameras in 35 countries, and “the number keeps going up rapidly,” says Vida.

The network consists of low-cost, highly sensitive video cameras connected to a tiny Raspberry Pi 4 computer which runs their free, open-source meteor detection software connected through the internet to the network.

Interested in joining the network? The cameras are deployed by expert and amateur astronomers; many installed the camera on their house or cottage. Operators can choose to build a camera from scratch using detailed online instructions, or purchase a ready-to-go system. Check out the GMN website to get set up or find out more.

The GMN has already garnered some international success as cameras in the UK observed the Winchcombe meteorite fall in February 2021, which resulted in the recovery of several meteorites.

Go further

View more images collected by the GMN

Citizen science: Observing meteor showers (by Ingenium’s Pierre Martin)

By Cassandra Marion

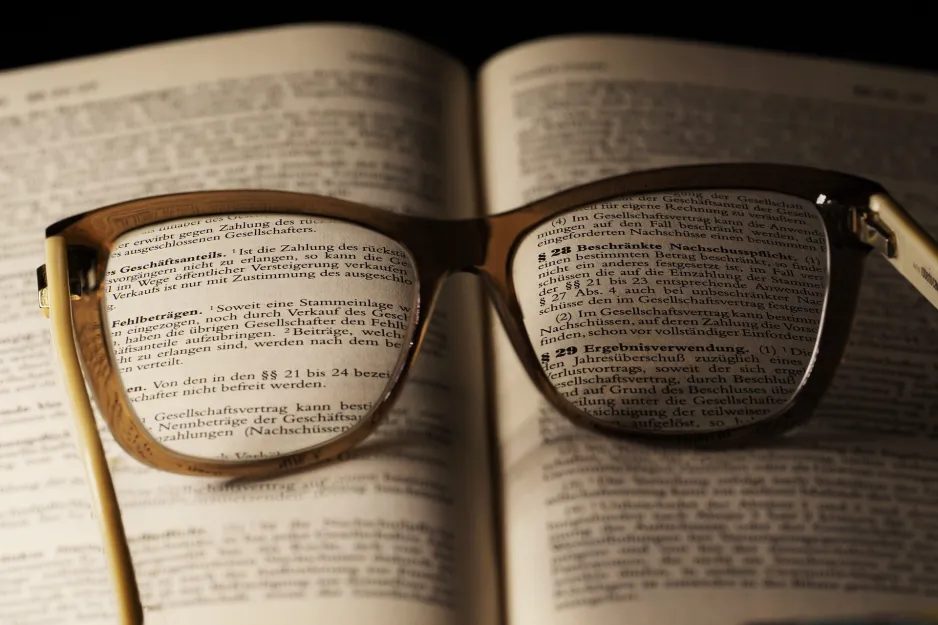

Since medieval times, reading glasses have helped many of us to clearly see objects.

Why reading glasses may be a thing of the past

I remember drawing a lot as a child. After I’d finished each masterpiece, I would run to my parents or grandparents to collect their exclamations of delight. In retrospect, those praises never came right away. I recall them saying, “turn on the light,” “let me find my glasses,” or “hold it a bit further from grandad’s face, so he can see it properly.”

Even though I could see my drawing clearly only two inches from my face, my older relatives needed a bit more distance. And the older they were, the further away the drawing needed to be held.

Why? Because of presbyopia: the condition where close-range vision gets blurrier with age.

Inside your eye, just behind your pupil, is a structure called the lens. Like the lens of a camera, the lens in your eye helps to focus light coming from multiple directions in order to create a clear image. To focus on objects at various distances, the eye’s lens must change shape. As people get older, their lenses get less flexible, which makes focusing more difficult. It’s a bit like a camera losing the ability to “zoom in” with age.

Presbyopia typically starts between 40 and 45, the stage of life when many people purchase their first set of reading glasses, or start using the magnify feature on their digital devices. However, glasses can be easy to misplace, and you can’t enlarge the printed text you would find in a book, newspaper, or menu.

A cool, new discovery looks to provide a more convenient option for dealing with presbyopia: eyedrops!

A new eye drop approved by the FDA in October 2021 uses an ingredient called pilocarpine to stimulate the pupil to shrink for about six hours. Reducing the pupil size means light enters the eye through a small hole, instead of a big one. This blocks light coming in haphazardly from many directions, which would normally blur the image the eye would see. By only permitting light entering from straight ahead, the result is clearer images. This natural ‘trick of the light’ is also why photographers use small apertures if they need to get more of their picture into focus.

So if you’re someone who prefers not to rely on reading glasses because you play sports, tend to lose your glasses, or have sticky-fingered children in your life who smear your clean lenses… this innovative solution may be just the thing!

Go further

How to see without glasses: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OydqR_7_DjI

By Michelle Campbell Mekarski

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!