3 things you should know about naming new animal species, the secrets hiding in lunar shadows, and possible new beneficial uses for spices

Meet Michelle Campbell Mekarski, Cassandra Marion, and Renée-Claude Goulet.

They are Ingenium’s science advisors, providing expert scientific advice on key subjects relating to the Canada Science and Technology Museum, the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, and the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum.

In this colourful monthly blog series, Ingenium’s science advisors offer up three quirky nuggets related to their areas of expertise. For the November edition, they tell us about the art and science of naming new animal species, how lunar shadows may hold the key to future space exploration, and how science is finding new uses for our flavourful spices.

The science of naming new species, or, why scientists can name frogs after Star Trek

In an exciting discovery, a group of scientists recently discovered seven new species of frogs in the forests of Madagascar. While trekking through forests and mountains, the team heard strange frog calls that reminded them of the sound effects from the Star Trek television series. The result? Seven new frog species, each bearing the name of a Star Trek captain: Kirk, Picard, Sisko, Janeway, Archer, Burnham, and Pike.

If you discovered a new species, what would you name it after?

Naming new species after science fiction characters may seem whimsical, but the process of naming a newly discovered species is significant. When scientists discover a new species, they don’t just catalog it and move on; they have to give it a name. And while there’s room for creativity (e.g., Star Trek frogs), the process has rules. This practice is known as taxonomy, “the science of classification,” and it’s essential for keeping track of Earth’s incredible biodiversity.

A global system

The official system for naming species, known as binomial nomenclature, was developed by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus in the 18th century. In this system, every species has a two-part name: the genus and the species. For example, in Homo sapiens, Homo is the genus, and sapiens is the species. The genus is always capitalized, while the species is lowercase, and both are usually italicized.

Having a universally recognized scientific name for each species is essential for communicating across languages and regions. This consistency helps scientists accurately identify and study species, share research, and track biodiversity on a global scale. Without standardized names, it would be easy for misunderstandings to occur. For example, the mountain lion is known by many names, including cougar, puma, catamount, panther, painter, and more. To scientists, it has one definitive name: Puma concolor.

The Naming Process: Rules and Guidelines

When scientists find a new species, they must follow the rules laid out by the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) or the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICNafp). These organizations ensure that names are unique and descriptive, and that every scientist in the world is following the same naming guidelines.

The name itself must be original and often reflects something about the species. Sometimes, the name describes a physical feature, such as the color or shape of the species. For example, the dinosaur Diplodocus longus is named for its distinctive long neck, with "Diplodocus" meaning "double beam" in reference to the structure of its bones and "longus" highlighting its remarkable length. Other times, scientists honour individuals in the names, such as Aptostichus stephencolberti, a spider named after comedian Stephen Colbert.

Creativity in Species Names

While the process is scientific, there’s room for creativity. Some names are humorous or playful, like the beetle Agra vation, which sounds like "aggravation." Others may reference pop culture, like the wasp Ampulex dementor, named after the soul-sucking Dementors from Harry Potter. These unique names can even help bring attention to species that might otherwise be overlooked.

Naming new species is more than a formality; it’s a way to celebrate and document Earth’s biodiversity. Each name carries a story, a bit of history, and a reflection of the world in which that species was found. And as long as there are new species to discover, scientists will continue to find fascinating ways to name them, connecting science with language, culture, and creativity.

By Michelle Campbell Mekarski

GO FURTHER: Some more amusing scientific species names

From darkness comes opportunity: permanently shadowed regions of the Moon

Some parts of the Moon never see the light of the Sun, and that’s a good thing for the future of human exploration.

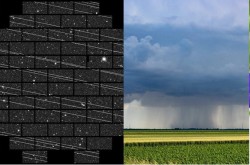

Permanently shadowed regions in impact craters near the south pole of the Moon.

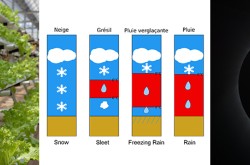

Located in topographic lows near the Moon's north and south poles, permanently shadowed regions (PSRs) are areas that are never directly illuminated by the Sun. While equatorial regions on the Moon experience 14 days of daylight followed by 14 days of night, the poles receive minimal sunlight due to the Moon's slight axial tilt of just 1.5 degrees. This contrasts sharply with Earth’s tilt of 23.4 degrees, which creates seasonal variations in daylight at the poles. As a result, the bottoms of certain polar craters on the Moon have been shrouded in darkness for billions of years, serving as cold traps.

Analyses from various spacecraft suggest the presence of water ice and possibly other volatiles in these PSR cold traps, though the precise quantity and the degree of mixing with lunar rocks remain uncertain. The Moon is generally a very dry place, but conditions vary significantly in these shadowed regions. Here, temperatures can plummet below -200°C, allowing water ice and other volatiles—like ammonia and methane—to accumulate. The possibility of water ice in PSRs was proposed decades ago, initially thought to be contamination until water molecules were identified in 2008 in volcanic glass samples from the Apollo missions. A variety of remote sensing instruments on subsequent missions, including Chandrayaan-1, the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS), and the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), supported the conditions for, and evidence of, water ice or hydrogen in the Moon’s polar regions.

This discovery has reinvigorated international interest in lunar exploration, as scientists hope to utilize this water ice for future missions. Extracted ice could serve as drinking water for astronauts, be used in cooling systems, and it could be split into oxygen and hydrogen for rocket fuel and life support. Refueling on the Moon or in lunar orbit would be far more economical than launching resources from Earth, given the greater fuel requirements to escape Earth’s gravity. If successful, a lunar fuel source would further enable exploration of the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

Cold traps are the only place water ice could survive on the Moon, as it would sublimate immediately in high temperature regions exposed to sunlight. There are several theories on how the water got into the PSRs, including impacts from water-rich comets, volatile-rich rocks ejected from craters, gases from ancient volcanic eruptions and/or hydrogen from solar wind that accumulated and reacted with oxygen in the regolith—the Moon's rocky surface material—over long periods of time. It is likely most of the water ice has been trapped for billions of years. Future missions aim to better understand the characteristics of this water ice—whether it exists as thick sheets or thin frost—and how mixed it is with the regolith, as well as to assess the overall quantity available for use. Capturing images in a place without light can be incredibly challenging, particularly when the cameras onboard LRO were not designed to do so. LRO is able to map out the topography using laser altimetry, measure the temperature and detect hydrogen in the lunar soil. A new instrument called ShadowCam, recently launched aboard a Korean lunar orbiter, aims to help. This ultra-sensitive light detector is 500 times more effective than existing Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Cameras and will use minimal light reflected from stars and surrounding surfaces to map the interiors of shadowed areas. This information will be crucial for better understanding what lies in the PSR, and assisting in planning safe routes for rovers and astronauts venturing into the dark.

By Cassandra Marion

The future of spices: harnessing plants’ defense systems for food preservation

Winter is upon us, and nothing warms our homes and hearts quite like the smell of spices wafting through our kitchens as we prepare our favourite seasonal recipes. Behind their deliciousness lies a wealth of science—and a lot of unexplored potential. What makes spices so tasty, and what future uses could they hold with the help of scientific research?

Spices contain a whole range of molecules that could be used to preserve our food and serve as medicines.

Spices, like cloves, cinnamon, and nutmeg, are essentially flavour-packed plant parts. While herbs refer to the fresh leafy and flower parts of plants, spices come from dried bark, stems, seeds, fruits, roots, flower buds, and even resin of certain plant species. Fresh ingredients like peppers, onions, garlic, and ginger can also be considered spices when dried, but are typically labeled as 'aromatics' when fresh.

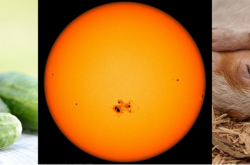

The flavour of spices comes from a variety of compounds they contain, known as allelochemicals. These are protective substances, part of the plant’s own defense system against bacteria, fungi, herbivores, and even competition from other plants. It's no surprise we often find these compounds concentrated in flowers, fruits, seeds and roots—the parts most vital to the plant’s growth and reproduction. Crushing or tearing plant cells releases these molecules, and when we eat them, they waft up our noses, where our brains interpret them as flavour. On our tongues, these compounds can cause sensations of bitterness, numbness, cold, or heat.

The widespread presence and use of spice today is likely due to a mutually beneficial co-evolution with humans. Researchers have explored why humans use spices, which has led to the idea that we have bred and spread spice plants around the world, not only because they taste good, but because they offered benefits for our health and survival. Humans have used spices and herbs for millennia—not just in cooking, but also to manage and heal health problems and, to some extent, to preserve food.

This makes sense when we consider spice chemicals as natural barriers for plants, that can act against the same types of microbes that cause illnesses in humans. In fact, many spices have been shown to inhibit or kill bacteria, with garlic, onion, allspice, and oregano being among the most potent. Humans have long known about the preservative effects of spices; for example, the ancient Egyptians used cinnamon in the embalming process. Some molecules in spices also have antioxidant effects, which help preserve oils and prevent decay caused by oxygen. Naturally, this has piqued the interest of modern scientific researchers, who are exploring whether we can tap into this natural laboratory for other human health and environmental benefits.

Thanks to their natural functionality, compounds from spices are beginning to be looked at by food scientists who see their potential for use as natural food preservatives, replacing synthetic ones used today. However, studies on the specific effects of these compounds on different foods and microbes are still sparse, and there is much more to learn before they can be widely adopted. For instance, what are the risks of unintended consequences, such as allergic reactions, long-term effects, toxicity, or interactions with other compounds that may enhance or diminish their effectiveness? As our understanding deepens, we might also find non-food applications for spices—such as prolonging shelf life or improving food safety with spice-based packaging and anti-microbial coatings.

Given how present spices are in our daily lives, and how long humans have been using them, it’s surprising how much we still have to learn about their health effects, their ability to combat microbes, and other potential uses. As demand grows for natural products, we can expect increased interest in exploring nature’s lab to discover new ingredients and solutions to our modern problems!

By: Renée-Claude Goulet

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!