The Face of the Rails: Black Porters in Canada

Black porters were integral to the day-to-day operations of Canadian railways from the late 19th to mid 20th century. The Black men who made up the majority of porters already experienced racism in Canadian society at large. In the context of their work, they faced the intensely racist and discriminatory policies of the railway companies and the white-led unions. These experiences made political and labour leaders out of many of them, as they fought discrimination on and off the rails.

The role of the porter became synonymous with Blackness and Black men in large part due to the work of American businessman George Pullman — the creator of the Pullman Sleeping Car Service. In the post-Civil War era, Pullman intentionally styled his sleeping car service after Southern great houses. By tapping into the recently emancipated Black labour pool, Pullman successfully mirrored enslavement era labour relations between white elites and Black workers. So ubiquitous was Pullman’s racially-charged influence in passenger train travel that Black porters came to be known not by their given names but by Pullman’s name. Passengers and railway staff alike often referred to them as “George” or “George’s Boy,” reflecting commonplace racist and paternalistic attitudes of the time.

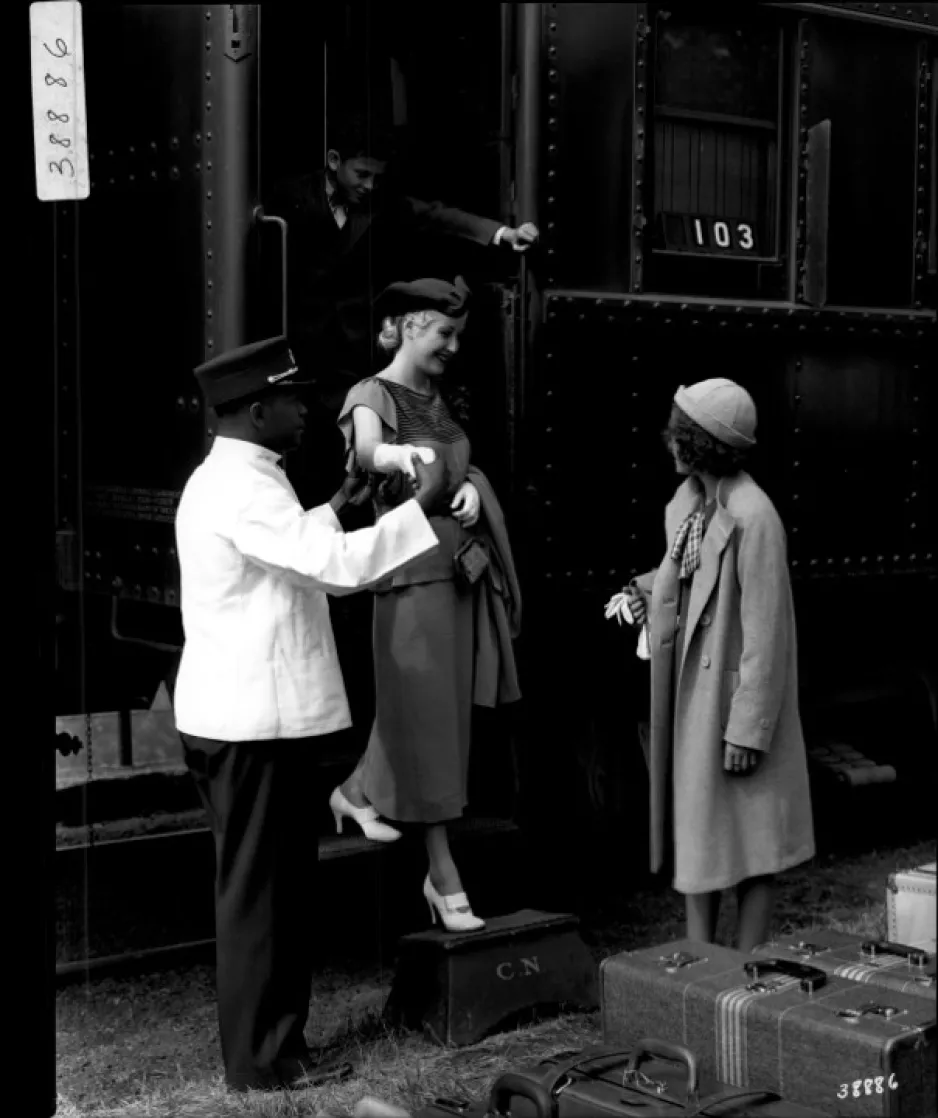

Porter helping a passenger disembark from the train.

When Canadian railway companies adopted the Pullman Sleeping Car Service after Confederation, they relied on similarly racist imagery. In Canada, Pullman services were available on the Intercolonial Railway, the National Transcontinental Railway, the Grand Trunk Railway, the Canadian Northern Railway, and the Canadian Pacific Railway. In 1923, when the Intercolonial Railway, National Transcontinental Railway, Grand Trunk Railway and Canadian Northern Railway merged to form Canadian National Railways, they launched their own brand of service similar to Pullman’s. Porters on Canadian rails were almost exclusively Black during this time as companies recruited from predominantly Black communities in Canada, the United States, and the Caribbean.

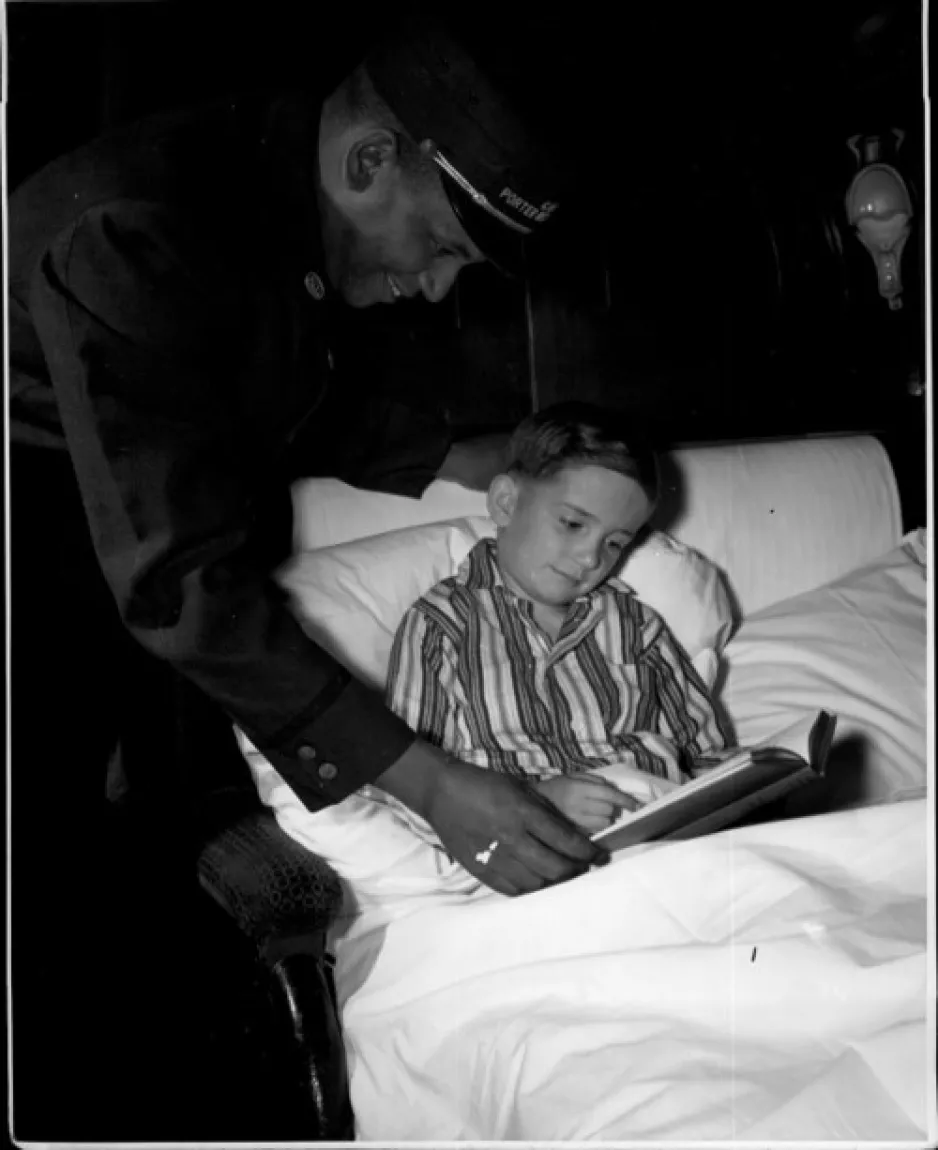

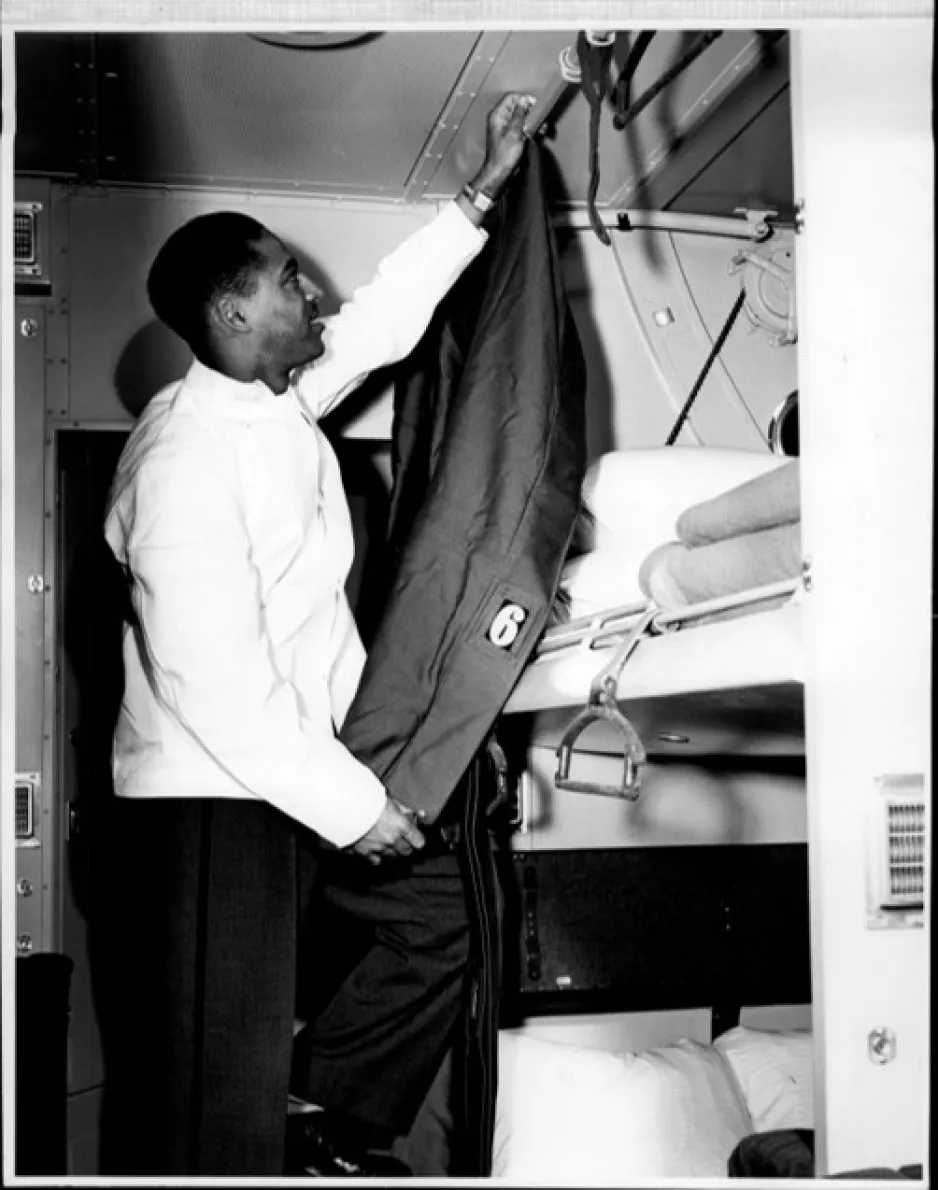

A porter’s job was extremely labour intensive. They were expected to be at the beck and call of passengers at any time during long overnight journeys. As a result they worked extremely long hours and were chronically sleep-deprived. Black porters were responsible for servicing all the passengers on their car, including receiving and disembarking, taking care of children and the sick, preparing berths, polishing shoes, and providing waiter service.

A porter checking on a child in a sleeping car.

Because porters were the first and last employees that passengers saw and spoke to, their interactions could have a significant impact on passenger loyalty and company success. To insure that success, railway companies required sleeping car porters to be unfailingly deferential, modest, and cheerful; to be attentive and always available when needed but silent and virtually invisible when not. The railways frequently used advertisements that depicted broadly-smiling, impeccably-uniformed Black porters ready to serve their mostly white railway clientele. This behaviour and image was reinforced by the fact that porters, due to their chronically low wages, relied heavily on tips to supplement their meagre incomes.

Behind the image of the happy and smiling porter, Black workers experienced a highly segregated workplace supported by railway companies and white-led unions. This meant Black porters were pigeon-holed into their low wage positions and were subject to discriminatory policies that their white co-workers did not face. Black porters had little or no hope of any kind of promotion within the railway, despite the size of these companies and the variety of jobs they offered. Many, if not most, white railway workers had access to training and promotion opportunities. Despite their very low wages, many porters were required to buy their own meals and uniforms and pay for their own accommodation while working, all at full price. They also had to reimburse the company for any missing items, like pillows and ashtrays, that might be pilfered by passengers. Railway companies financially benefited from maintaining a segregated workforce and often pitted Black workers against white-led unions.

Black railway workers were excluded from membership from white-led unions in the first part of the 20th century. In fact, the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees (CBRE) actively fought for separate contract negotiations and employee benefits for white and Black workers. Resistance to these exclusionary policies from Black porters did eventually gain Black workers access to the CBRE, when the union got rid of its white only membership clause in 1919. However, the CBRE still maintained an internal racialised hierarchy by segregating Black members into auxiliaries which gave them sub-membership status within the union. Despite consistent advocacy from Black workers, discriminatory policies from railway companies and unions would not fully disappear until the 1960s.

A porter prepares an upper berth.

Although railway companies and unions attempted to squash Black resistance to many of these policies, they were never entirely successful. For example, in 1917, Black workers formed the Order of Sleeping Car Porters (OSCP), one of the earliest Black railway unions in North America. In the 20th century the OSCP would go on to successfully negotiate contracts for Black workers on every major Canadian line.

In addition to their constant struggles with railways companies and white-led unions, Black porters were also prominent figures in their communities. Many became powerful political actors who built national coalitions, won legal battles, and resisted racial discrimination wherever they found it. Porters established programs to provide essential services to Black communities across Canada. Canadian cities with major railway hubs became the locus of vibrant Black communities as local residents built small businesses, community spaces, and lodging houses to support burgeoning Black populations. Many of these became common gathering places for porters during their travels, spaces where they could socialise, share news, and organise against racial oppression. As many porters travelled across the continent, their mobility allowed them to share ideas, politics, news, and to develop an awareness of issues facing Black people throughout North America. Through these exchanges they developed and nurtured strong transnational bonds and perspectives. The legacy of Black porters and their steadfast resistance to racism is reflected in Black political organising and activism in Canada today.

A porter stands on train steps.

Further Readings:

Foster, Cecil. They Call Me George: The Untold Story of Black Train Porters and the Birth of

Modern Canada. Windsor: Biblioasis, 2019.

Grizzle, Stanley G, and John Cooper. My Name’s Not George: The Story of the Brotherhood of

Sleeping Car Porters : Personal Reminiscences of Stanley G. Grizzle. Toronto: Umbrella Press, 1998.

Mathieu, Sarah-Jane. North of the Color Line: Migration and Black Resistance in Canada, 1870-

1955. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!