Sing us a song, you’re the weatherman: Jacques Lebrun and the conquest of space

As was said (typed?) by a somewhat reckless individual, namely moi, while it is true that working for an institution such as the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, can sometimes be difficult, it is also true that the resources and treasures it preserves are unmatched in this country. Yours truly has dug in these resources on many occasions over the past 3 decades. I will not do so today, my reading friend.

You see, today’s topic has little to do with aviation. I know. I too share your deep disappointment, but there is more to life than airplanes. Space and astronomy are at the heart of this week’s peroration.

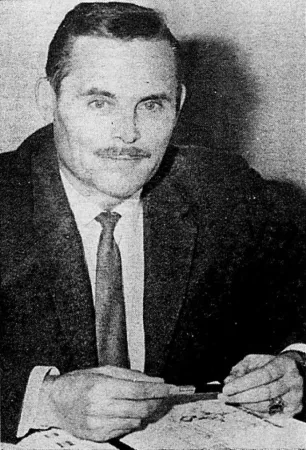

Be that as it may, the individual at the very heart of said peroration was / is a person I often saw on television, in ancient times. During the 1960s and 1970s. It would, however, be an exaggeration to say (type?) that this individual was one of my heroes, and… That’s precisely what I said in a June 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, you say? Are you sure? Hmmm, good.

Jacques Lebrun was born in France, the land of my ancestors, in January 1928. From an early age, he was interested in aviation. Lebrun was deeply impressed by the launch of German A-4 / V-2 rockets and Fieseler Fi 103 / V-1 cruise missiles in 1944-45 in the vicinity of the city where he lived. The journalist who collected his words in July 1994 may have misunderstood them. Lebrun’s memory may also have been be faulty. In fact, Lille was seemingly one of the targets of the first ballistic missile in the world, the (in)famous V-2. There did not appear to be any V-1 launch pads near this city either. You will remember that Wernher Magnus Maximilian von Braun, a character mentioned in January, February and September 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, oversaw the design of the V-2.

Around 1947, just after his marriage, Lebrun proposed to his wife that they immigrate to Canada. The latter showing little enthusiasm for this idea, the young couple remained in Europe.

It should be noted that Lebrun obtained a diploma in industrial design at an indeterminate date.

A meeting, in 1956, with an agronomer, sorry, an astronomer was a turning point in the life of Lebrun. The 2 men become friends and Lebrun discovered a passion for astronomy and a brand new field of research, astronautics. In fact, he soon became a member of the Société Astronomique de France, an organisation mentioned in a June 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Yours truly wonders if said (amateur?) astronomer was not the childhood friend with whom Lebrun spent a night, in early October 1957, trying to follow the route taken by the first artificial satellite, Sputnik I, a Soviet spacecraft mentioned in several issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since July 2018. The 2 men spent other nights trying to follow the routes followed by other artificial satellites. Lebrun’s friend was Pierre Neirinck.

This nestor / leader of the community of satellite tracking enthusiasts was fortunate enough to turn his favorite hobby into paid employment in 1966 when he joined the staff of the British Satellite Orbits Group. He thus found himself at the Radio and Space Research Station, the main British tracking station, during the Apollo 11 mission in July 1969, a mission mentioned a few times in our blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since May 2019. Neirinck supervised a team which provided basic data to the United Kingdom’s network of amateur observers. Indeed, Neirinck apparently became the head of the Satellite Orbits Group in the early 1970s. He took an early / unplanned retirement in 1980 or 1982 when the government led by British Prime Minister Margaret Hilda Roberts Thatcher, a person but not a lady mentioned in an April 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, reorganised its satellite tracking services.

Back in France soon after, Neirinck remained active in the community of satellite tracking enthusiasts virtually until his death, in early January 2016, at the age of 89. For example, he distributed site codes from the Committee on Space Research of the International Council of Scientific Unions, an organisation mentioned in a September 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, to many new observers and observation sites, but back to our story.

Lebrun immigrated to Canada in 1961 with his family. He then thought of moving to Hamilton, Ontario, to find a job in the iron and steel industry. While in Montréal, Québec, for a short period of time, Lebrun was offered a job as a night watchman in Kahnawá:ke / Caughnawaga, a Six Nations reserve not far from the metropolis. Unwilling to earn $ 85 a week for 85 hours of work for the rest of his life, he left the position after 2 months to work as an industrial draftsman in a large Montréal firm.

In 1962, still fascinated by astronomy and astronautics, Lebrun became a member of the Centre français de Montréal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, today’s Centre francophone de Montréal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, a group mentioned in a June 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. He was actually among the people present at the first popular astronomy evening organised by the centre, in October 1961. Although completely devoid of scientific training, Lebrun’s enthusiasm soon got him noticed. He began to give lectures on space flights in 1962.

At the popular astronomy evening of 1965, Lebrun delighted his audience with a presentation on the Apollo program of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), an organisation we all know mentioned in many issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since March 2018. He had with him one or more scale models of rockets.

It should be noted that Lebrun wrote a column on astronautics in the magazine of said Centre français de Montréal, Le Bulletin d’astronomie, between July 1965 and November 1969.

Around 1963, a representative from the centre mentioned his name to a representative of the Société Radio-Canada who was trying to find a person who could talk about the planet Mars on the radio. The Canadian national radio and television broadcaster had no one on staff who knew about astronautics. Lebrun’s performance, another turning point in his life, was so impressive that the management of the Montréal radio station CKAC, the first French-language radio station in North America and then owned by the major Montréal daily La Presse, soon offered him a position as a meteorological and scientific columnist. Lebrun who, let us remember, was completely devoid of scientific training, read everything that came to hand so as not to blunder on the air.

Around 1964-65, Lebrun was invited to talk about space exploration on at least one episode of Aujourd’hui, a public affairs magazine of the Société Radio-Canada which made history by attracting more than one million television viewers before leaving the airwaves in 1970.

In December 1965, Lebrun described the launch of NASA’s Gemini VII mission for CKAC listeners. Let us note in passing that the crew of Gemini VI-A got within 30 or so centimetres (1 foot) of Gemini VII, completing the first space rendezvous. One of the 2 astronauts aboard Gemini VI-A, Walter Marty “Wally” Schirra, was mentioned in June 2018, June 2019 and July 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

The inauguration of the Dow Planetarium in April 1966 was another turning point in Lebrun’s life. Affected by a bout of digressing fever, yours truly is forced to pronounce (type?) a few words about this remarkable institution. The birth of the Dow Planetarium was in all likelihood the result of a happy coincidence. Around 1963-64, Pierre Raoul Gendron, a former chemistry professor and founding dean of the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Science who loved astronomy, happened to be chairman of the board of directors of Dow Breweries Limited, one of the leading breweries in Québec.

Would you believe that the father of yours truly was / is one of the countless Quebeckers who quenched their thirst with a Dow and / or Black Horse during the 1950s and 1960s? Profuse apologies, I digress.

Around 1963-64, say I, Dow Breweries decided to fund the construction of a world-class planetarium in Montréal. This exceptional philanthropic initiative was part of the preparations for the inauguration of the Exposition universelle et internationale de Montréal held in 1967. And yes, my reading friend, Expo 67 was mentioned in March, July and December 2018 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

As the Dow Planetarium presented its first show, and please be aware that what follows is not at all amusing, Dow Breweries faced a horrible rumour: its products seemingly contributed more or less directly to the death of 20 (?) heavy drinkers in the Québec, Québec, area, all victims of heart problems of unknown cause between August 1965 and April 1966.

According to the press, the brewery had added a product to the Dow, on an experimental basis, to give it a nice collar of foam, a very popular feature in the region of the old capital. What was not said, or what was not known, was that other Canadian breweries, many American breweries and at least one Belgian brewery were using the same product, sometimes with the same result. Well over 40 people died in 3 American states and in Belgium between 1964 and 1967, for example.

Fearing for their lives, consumers across Québec abandoned Dow Breweries products in droves, putting its profits in freefall. The investigation reports which concluded that there was no clear link between the deaths and the latter’s beers reassured no one. Rothmans of Pall Mall Canada Limited, a well-known Canadian cigarette manufacturer, acquired Dow Breweries in 1969.

The Dow survived this change of ownership and to others until around 1998, however, the date of its final passing. It even won 3 international prizes between 1968 and 1970, but back to our story.

In the months and years following the opening of the Dow Planetarium, Lebrun hosted a number of presentations / conferences, under the direction of the institution’s first scientific director, Auray Blain, a botanist and geneticist who had worked at the Jardin botanique de Montréal, an organisation well known in Québec and elsewhere mentioned in a June 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Lebrun also became a member of the Société d’astronomie de Montréal, an independent body founded by the aforementioned Centre français de Montréal, shortly after its creation, in June 1968. An advisor to the organisation in 1969-70, he held the position of president in 1971-72.

A Montréal-based private broadcaster mentioned in a June 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, Télé Métropole Incorporée, placed Lebrun on the team which commented the flight of the aforementioned Apollo 11 mission in July 1969. His was limited to comments of a technical nature role, however. Lebrun readily admitted that he did not speak much.

Indeed, Roger Baulu, a well-known Québec radio and television host nicknamed the prince of announcers, was responsible for commenting on the bulk of what was happening, in collaboration with Montréal journalist Gilles Deschênes. Télé Métropole, an organisation that no one accused of having too intellectual a programming, ultimately presented more than 24 hours (27 hours? 30 hours?) of colour reports produced in collaboration with the American network National Broadcasting Company and the Canadian network CTV Television Network.

This televised marathon was a massive hit. Yours truly was one of the countless Quebeckers who watched at least part of the show. In fact, Télé Métropole received hundreds of congratulatory letters and thousands of congratulatory phone calls. Many of these people, however, wished to have additional information.

The performance of Lebrun during the Apollo 11 mission was so impressive that the management of Télé Métropole made him its in-house space flight expert.

The Apollo 12 mission of November 1969 gave rise to a somewhat amusing episode. As Lebrun commented on the journey of the American spacecraft, the image on the screen showed Pope Paulus VI / Paul VI, born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, speaking to a multitude of people. Some viewers believed that he too was commenting on this wonderful realisation of the human intellect. In fact, Paul VI was asking Catholic activists around the world to support their church, which was facing serious problems. Fifty years later, one has to wonder if things have changed.

Given the reaction of the Montréal and Québec audiences during the Apollo 11 mission, Télé Métropole’s management launched the television series Conquête de l’espace, hosted by Lebrun and intended for the general public, in September 1969. A second series of episodes followed in September 1970. The 2 series of episodes (26 + 26), which lasted 30 minutes, were apparently not presented at peak times. If Télé Métropole wanted to talk about space, it had no intention of wasting airtime and / or risking advertising revenue. It was probably around this time, no later than 1969 that is, that Lebrun was given the moniker “prof / professeur Lebrun.”

Responding to the wishes expressed by many television viewers, and by many people attending the aforementioned presentations / conferences at the Dow Planetarium, Lebrun collected his notes and published a book in a language that was clear, direct, precise, simple, etc., in January 1971 in the colours of the Éditions de l’Homme of Montréal.

La Conquête de l’espace, by Jacques Lebrun

Officially launched at said planetarium, just days before the start of the Apollo 14 mission, a mission mentioned in June and July 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee that Lebrun commented on masterfully, said book, La Conquête de l’espace, and I quote the contents of the back cover of the book, in translation of course,

PRESENTS the balance of our current knowledge in the field of space taking into account the most recent discoveries, many of which are still unknown to the public.

EXPLAINS the incredible path traveled by astronomy from ancient times to the present day.

PROVIDES INFORMATION on life in the Universe; the structure of the planets; celestial mechanics; cosmic radiation and relativity.

ENLIGHTENS on space research, its objectives and its means.

The daily La Presse published some comments on the book:

“La Conquête de l’espace” (Éditions de l’Homme) is an eminently current book, with a simple presentation and abundantly illustrated.

The reader will find an answer to most of the questions that her / his curiosity turns on: she / he will see that science is not that complicated when one understands.

Mr. Jacques Lebrun reaches out to each one of us and transports us smoothly and painlessly into the fascinating world of Space. In this sense, he is an educator.

He goes further and becomes a polemicist in a chapter on the social aspects of space exploration; he reviews the pros and cons of current opinions on the merits of conquering space. He takes a stand.

Yours truly must confess to fond memories of La Conquête de l’espace. I read and re-read my copy, purchased in the early 1970s, until pages, then entire sections came off the cover. I must also say that, around 2018-19, I asked the librarians of Ingenium Canada, the group of museums that includes the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, where I earn my crust by the sweat of my follically challenged brow, to buy a used copy of Lebrun’s book. A big thank you for this purchase, FSH and CH – and for other book purchases, past, present and future.

La Conquête de l’espace was / is in all likelihood the first French-language scientific communication / popularisation book published in Canada devoted to astronomy and, I repeat and, astronautics. Before you hit the roof, my scholarly reading friend, I take good note of the fact that Brother Robert, born Étienne Poitras, a member of the congregation of the Frères des écoles chrétiennes, an institution mentioned in an April 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, wrote more than 10 textbooks used for teaching and popularisation books from 1930 onward, including 4 related to astronomy: Astronomie élémentaire (1931), Précis d’astronomie élémentaire (1934), Regards sur l’univers (1948) et Les astres et les lettres, in 2 volumes (1950 et 1952).

Would you believe that this brilliant Québec mathematician defended a doctoral thesis at the Université de Lille, in France, in June 1939? His thesis was on… agronomy, sorry, astronomy. Would you also believe that both Lebrun and Neirinck were born in / remained in Lille during their childhood and youth? Small world, isn’t it?

If I may be allowed a comment, Brother Robert is so interesting that I will try to find a photograph of him in a Québec daily or weekly in order to devote to him one of our scholarly and erudite articles.

Several members of the Département de Physique of the Université de Montréal, an organisation mentioned in a September 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, strongly reacted to the publication of La Conquête de l’espace. Dare I say that this group of academics, which included the director of this department, as well as at least 2 professors and 5 graduates, attacked this book with a somewhat surprising virulence that deeply hurt Lebrun?

One of the 2 professors of said Département de Physique denounced Lebrun’s book, full of errors according to him, on the airwaves of the Société Radio-Canada, for example.

It should be noted that the 2 aforementioned professors, apparently quite young, joined the faculty of the Département de Physique around 1968-69 following steps taken by Serge Lapointe, a former director of said department who had become dean of the Faculté des Sciences of the Université de Montréal in 1968 and a gentleman mentioned in a September 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. But back to our story.

The members of the Département de Physique reported their grievances in the pages of Forum, the internal publication of the university. They apparently wrote to several newspapers, including La Presse, which publishes their missive in February 1971. These same members sent letters to some Collèges d’enseignement général et professionnel (CEGEP) in the Montréal area. They may even have written to high-ranking Québec personalities.

La Presse also published a letter, possibly sent independently, by a student at the same department who was not part of the group mentioned above.

These members of the Département de Physique did not seem to appreciate the colourful style of Lebrun, described as flights of speech or verbiage. A star could not catch a cold, cough or spit, they said. Said members, however, reserved the bulk of their criticism for the many factual errors, the often erroneous calculations and graphs and the use of somewhat old hypotheses set aside by the scientific community they met over the pages. The absence of a bibliography did not go unnoticed.

The letter published by La Presse ended with the following paragraph, quoted in translation:

It is therefore to be hoped that the Éditions de l’Homme will avoid putting this book on the French market, at least before a complete revision by someone competent. If not, will they take the precaution of indicating to the bookseller that the work should be placed on the same shelf as La Foire aux Cancres.

Ouch…

By the way, La Foire aux Cancres was / is one of the classics of French literary humour. Published in 1962, this collection of pearls, in other words unintentionally amusing little sentences, was / is one of the works of this type written by the writer and humourist Jean-Charles, born Jean Louis Marcel Garen Charles.

If yours truly may be permitted a comment, the style of the letter of the members of the Département de Physique differed somewhat from that found in articles published in the Canadian Journal of Physics.

A response from Lebrun published a little later in La Presse included a quote related to these people whose origin yours truly unfortunately does not know (Synthesis of opinions expressed by the academics? Extract from a letter sent to the Dow Planetarium?? Something else???). According to the members of the Département de Physique, La Conquête de l’espace, and I quote, in translation,

was unacceptable, lacked seriousness and had innumerable mistakes. As for the author, he damaged the honour of astrophysicists, flouted science and did harm to astronomy, particularly in the province of Québec. [Lebrun] should be replaced by people far more competent in his activities, either during television reports, as a speaker at the Dow Planetarium or as president of the Société d’astronomie de Montréal.

Ouch squared.

A detail if I may be permitted. One of the members of the Département de Physique may, I repeat may, have called Lebrun an impostor, a crook and a charlatan during a very friendly telephone conversation.

Sensing a controversy / juicy story, the editorial office of La Presse published the letter of a reader who wished to defend Lebrun. Yours truly wonders if this missive was the only one that the daily received. Anyway, let’s continue our story.

If said reader did not affirm that La Conquête de l’espace was an error-free book, he wondered if the criticism of the members of the Département de Physique, and I quote, in translation, “victims of collective psychosis, where individual responsibility was lost,” was “truly unbiased and motivated by a true scientific mind or if it was not inspired rather by a sense of frustration from learned scholars facing the success of a man without a degree in this field.”

Ouch cubed.

To that end, let me note that Lebrun mentioned at that time, in 1971, that one of the people full of diplomas who had attacked him made a presentation at the Dow Planetarium. Dare quote this man without a degree? I dare: “It was a disaster. An outcry of protest from the audience, because even a specialist could not get 20% of his incoherent remarks.”

If yours truly may be permitted a small comment, some people know how to pass on information to a group of people so that they will not yawn their head off, or move to the edge of a nervous breakdown. Other people, as bright as they are, do not have that talent. Sheldon Lee Cooper, a brilliant theoretical physicist in the American television series The Big Bang Theory, for example, sucked the big one when he appeared before a group of university students. But back to the reader of La Presse who defended Lebrun.

Noting that the members of the Département de Physique did not like the all too popular style of Lebrun, our reader suggested that a person with the slightest common sense fully understood that a star could not catch a cold, cough or spit. Their remark was therefore wrong.

This being said (typed?), yours truly, who willingly admits that he is no expert on the subject, and far from it, wonders if the defence provided in the case of the factual errors examined by the reader of La Presse, who also admitted he was not an expert on the subject, actually held water. Speaking of expertise, I must indeed admit having sweated blood and water throughout my physics courses in hard and complicated sciences, sorry, in pure and applied sciences, at the CEGEP of Sherbrooke, Québec, my homecity, in 1975-77. But I digress. Profuse apologies.

In other words, said reader whose letter appeared in La Presse did not necessarily manage to counter the attacks by members of the Département de Physique regarding the factual errors specifically mentioned in their letter to the Montréal daily.

For example, I must point out that the members of the Département de Physique were right to say they were surprised to read in La Conquête de l’espace that the gravitational force of a celestial body increased with the speed of rotation of said body. In fact, a person at the equator of our good old Earth, where everything went around pretty darn fast, experienced a gravitational force slightly smaller (about 0.03%) than that experienced at the North Pole – or the South Pole.

At a press conference held in mid-February 1971, at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, a Montréal institution mentioned in a March 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, Lebrun gave his version of the facts. He readily admitted that, just like Lionel George Logue, the Australian speech therapist specialising in elocution highlighted in the superb 2010 film The King’s Speech, mentioned in a November 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, he was purely self-taught. Lebrun admitted that his book contained errors for which he held himself accountable as well as others attributable to his concern to popularise / communicate his subject well.

This being said (typed?), Lebrun castigated the academics who had denounced him. He denounced what was for him a campaign of relentless / systematic / virulent denigration. In fact, Lebrun believed that the members of the Département de Physique did not seek so much to discredit his book as him, as a person.

You see, the founding director of the Dow Planetarium, the American astronomer and former deputy director of the Fels Planetarium of the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Donald D. Davis, was soon to retire. Lebrun said he was approached to ensure his succession. He added that a scientist (teaching at the Département de Physique of the Université de Montréal?) was also approached to succeed Davis. According to Lebrun, the virulence of the attacks of the members of said department followed from this situation. Yours truly has unfortunately been unable to prove or disprove Lebrun’s hypothesis.

The public’s enthusiasm for his book was the most eloquent answer Lebrun could make to his denigrators, said he at the press conference.

In the end, the board of directors of the Dow Planetarium chose the aforementioned Blain to succeed Davis a little later in 1971.

Lebrun, meanwhile, was not “replaced by people far more competent in his activities, either during television reports, as a speaker at the Dow Planetarium or as president of the Société d’astronomie de Montréal,” as the aforementioned members of the Département de Physique wished / demanded. Let us mention as an example that Lebrun commented on the Apollo 14, 15 and 17 missions between February 1971 and December 1972.

The end of the Apollo programme, which took place in December 1972 with the Moon landing of Apollo 17 mission, resulted in a sharp drop in the number of people crossing the doors of the Dow Planetarium. Strongly concerned by this situation, which also affected the activities of the Société d’astronomie de Montréal, Blain launched the idea of presenting shows intended for a school audience, a clientele which had been relatively ignored previously by the staff of the Dow Planetarium. He actually collaborated with Lebrun to create a first show destined for said clientele, Le royaume du Soleil. The latter was pleased to present said show, and those which followed thereafter, to tens of thousands of schoolchildren and students.

And yes, Apollo 17 was mentioned in a June 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Lebrun also replaced the assigned meteorologist of Télé Métropole, the very popular Raymond Lemay, for a few days during the summer of 1969. His performance was so satisfactory that he seemed to have landed the position of assigned meteorologist. Lebrun not being a meteorologist, he was still reading everything that came to hand so as not to blunder on the air. This lack of knowledge largely explained his rather colorful presentation style.

Indeed, this same style seemed to be at the origin of a (brief?) return to the airwaves of Lemay, on the show La couleur du temps of Télé Métropole, in 1971. Lebrun and the latter seemed to alternate at irregular intervals over the next months and years. This being said (typed?), Lebrun contributed to La couleur du temps at least until 1986.

For one reason or another, the technical team that ensured the broadcasting of La couleur du temps liked to make fun of Lebrun. One day, for example, one of these people crawled on the floor of the studio, unbeknownst to viewers, to tie up his shoe laces. Lebrun, imperturbable, read his weather report as if nothing had happened.

Lebrun was also part of the team of the popular children’s show Patofville, also at Télé Métropole, around 1974-75. His character, Monsieur Qui, a scholar visiting / lost in this imaginary city, familiarised many young Quebeckers with certain scientific phenomena and with the metric system, introduced in Canada from 1975. And yes, Patofville was mentioned in another November 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, and… What is it, my reading friend? That’s precisely what I said (typed?) last week? No… Impossible, unless Q the magnificent, Q the omnipotent, Q the royal pain in the posterior changed the space time continuum. Again.

May I be permitted a wacky idea, my reading friend able to tolerate many eccentricities? Yours truly wonders if the name of the character of Lebrun, Monsieur Qui, which means Mister Who, derived from the name given to a very old extraterrestrial being, known only as the Doctor, who was the hero of the British television science fiction series Doctor Who, mentioned in August and October 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee. Just sayin’.

Lebrun left the Dow Planetarium in 1978 to focus on his career in meteorology, which he considered very important. In fact, he felt himself to be on duty at any time of day or night. Snowstorms did / do not work 9 to 5.

That same year, Télé Métropole nonetheless entrusted Lebrun with the position of host of Les chemins de l’inconnu. This television series, aired from September, examined topics related to science and technology that were sometimes controversial / mysterious / original / paranormal, in other words fortean subjects, bidet, sorry, sorry, be they Les satellites de communications or Uxmal, la ville des lieux sacrés, a Mayan urban centre whose ruins are in Mexico.

And yes, my reading friend with a sharp and curious mind, Les chemins de l’inconnu may very well have been the Québec counterpart of the American television series In Search of, broadcasted between April 1977 and March 1982 – and mentioned in a July 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Would you believe that the term fortean was mentioned in some issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since October 2018? Long live Charles Hoy Fort – and French fries with mussels and a good beer! Sorry.

Lebrun had excellent memories of trips to Peru and Mexico made as part of Les chemins de l’inconnu. He actually had excellent memories of this series which remained on the air, in reruns, until about 1984.

Busy with his work, Lebrun travelled very little indeed. In fact, he gave himself a vacation only in 1976, to visit his daughter, in Spain, with his wife. Their son, on the other hand, lived in Québec.

Lebrun’s long working hours reduced his leisure time to little. He liked to paint, however, with his wife. If the latter had taken some lessons, Lebrun, true to his habits, was purely self-taught.

All in all, Lebrun participated for about 28 years in morning programs broadcasted by the aforementioned radio station CKAC. He was responsible for the meteorological and scientific chronicles. This being said (typed?), Lebrun also worked at 3 other (independent?) commercial radio stations in the Montréal area. At one time, he made about 15 or so weather reports a day. Did you know that this workaholic had a radio studio in his home, possibly created with the help of one of his employers? Yours truly does not know when Lebrun retired, assuming he actually did so.

Lebrun died in October 2003, at the age of 75. The highlights of his many careers were highlighted in newspapers, on radio and television, in Montréal and elsewhere in Québec.

The author of these lines wishes to thank all those who provided information. Any mistake in this article is my fault, not theirs.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)