Collecting Nahma: A skiff with a story to tell

Museum curators collect artifacts because of what they can tell us about the past. We are trained to look at objects critically and assess their importance as rationally and objectively as possible. While this information is important, it’s really only the beginning of our research. Every human-made object has what you might call a ‘life story.’ That story encompasses not just makers and users, but the many other people who have had contact with or taken an interest in the object and its history.

When we pursue this type of research, it can take us in unexpected directions — drawing us into a rich and complex web of Canadian history, local identity, and personal memory. It also introduces us to the many remarkable people who know and have cared for the artifact and whose stories become part of it. So it was with my journey into the world of an old, wooden sailboat called Nahma.

The Collingwood skiff, Nahma, is the last surviving example of a type of boat that once dominated the fisheries of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay. Fishing Fleet, Collingwood Harbour, circa late 1880s.

The lone survivor

The Collingwood skiff Nahma is the last surviving example of a type of boat that once dominated the fisheries of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay. Though never used as a commercial fishing boat, it is true to the original, late 1850s design and was built by the originator of the type, William Watts & Sons of Collingwood, Ontario. It embodies evidence of two industries — wooden boat building and the fishery — that many hundreds of Canadians depended upon to make a living during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Nahma is a physical link to that world, revealing not only the fine craftsmanship of Collingwood boatbuilders, but also the skill demanded of fishers working from open, sail-powered boats on the treacherous waters of Lake Huron.

Nahma’s last owner, Mr. Ken Jones, understood the deep connection between the town and the last Watts-built skiff; he insisted that the boat be retired into the care of the Collingwood Museum upon his death in 1994. Honoured to have this special boat back ‘home,’ the town began to plan for its long-term care and public display. But, like many local heritage institutions, the Collingwood Museum has limited display and storage space. In order to accommodate Nahma, they needed to build an addition. Unfortunately, after years of trying, they just couldn’t find the resources to look after this rare and fragile boat. Early in 2012, museum staff began the process of finding a new home for Nahma. In keeping with the wishes of Mr. Jones, they turned to the Canada Science and Technology Museum in Ottawa.

A symbol of local identity

When Susan Warner, then supervisor of the Collingwood Museum, first contacted me about Nahma, I treated it as just another offer of an object, albeit from a museum rather than an individual. Based on our usual criteria, this was an important artifact and I knew we would be happy to have it in our collection. But as Susan spoke about the boat and the situation in Collingwood, I quickly became aware that there was much more to Nahma than its obvious national significance — and this would be anything but a routine acquisition.

Susan knew her community and its history very well and had devoted her considerable talents and energy to documenting, preserving, and sharing that history. She understood that Nahma had come to represent more than just the town’s boat building and fishing industries. It embodied the achievements of generations of Collingwood residents, whose knowledge and skill in working with local materials had produced hundreds of boats uniquely suited to the needs of the fishery and its harsh environment. In an age of globalization, mechanization, and mass-production, Nahma had become a rare and powerful symbol of collective achievement and local identity.

Susan also heard from the family and friends of Ken Jones, whose knowledge of wooden boat building and devotion to Nahma had preserved this elderly boat for posterity. In addition to their strong emotional attachment to this boat, they were concerned about its long-term survival — given the Collingwood Museum’s lack of appropriate storage space. For them, Nahma’s care took precedence over it remaining in the town where it was built. They believed that, after almost 10 ten years in Collingwood, it was time to transfer the boat to Canada Science and Technology Museum in Ottawa.

Susan knew that the decision to transfer Nahma to Ingenium was the right one; but she also knew that it would be controversial. She had to make a strong case to both her immediate supervisors and to city council. She explained the infrastructure needed to house Nahma and what it would cost, and reviewed the history of planning and fund-raising for the space since 1994. She also presented the donor’s family’s concerns and their wish to have the boat transferred to Ottawa. Throughout this long, drawn out, and politically-charged process, Susan gently reminded everyone that the boat’s survival took precedence over political or personal considerations. In the spring of 2013, a year after our initial conversation, Susan finally got official permission to transfer Nahma to the national collection.

The moving team carefully lifts Nahma onto a special truck for transport from Collingwood to Ottawa.

A fond farewell

Keenly aware that this outcome would represent an emotional loss for many members of her community, Susan and her staff decided to plan a public farewell for Nahma. Their goal was to celebrate the boat and the community that had produced it, and to demonstrate that its departure would actually help to make Collingwood and its boat-building achievements part of a shared national heritage. In keeping with that goal, Susan invited me to come to Collingwood and give a presentation highlighting the incredible richness of Nahma’s history, its deep connections to the region, and its outstanding national significance.

Susan also invited Ken Jones’ sister Frances, nephew Mark Adams, and other ‘friends’ of Nahma to help with the send-off. Local media were fully briefed and present at the event. The following day, the public were invited to the grain elevator on the waterfront, to watch as the boat was carefully moved outdoors and lifted onto a special truck for transport to Ottawa. Susan turned what could have been an entirely solemn occasion into a celebration of Nahma and of Collingwood’s brief, but important, stewardship of this rare, historical treasure.

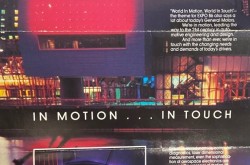

Ken Jones and crew take advantage of calm waters to relax and enjoy the sunshine.

Personal connections

The farewell party marked the beginning of my reckoning with the unexpected and often personal meanings of artifacts. The media coverage of Nahma’s transfer to Ottawa prompted people who ‘knew’ Nahma to contact me. Their reminiscences — through stories, contacts, and photos — sent me back to look at the boat and its history with fresh eyes.

What I found surprised me. The people who know about Nahma understand the boat’s technical importance. But when they talk or write about it — even when they are discussing practical things like construction or performance — they speak of it as if it were a living thing.

Boat builders and small craft historians wax poetic about Nahma’s beauty, its simplicity and purity of form, the fineness of its planking, its sturdiness, and longevity. Fisheries historian Lorne Joyce saw Nahma as the keeper of knowledge and memory for generations of boat builders and fishers on the Great Lakes. He looked upon Nahma with great pride and a little sadness, and was fiercely protective of it — especially after the death of its last owner, Ken Jones.

For the people who actually sailed on Nahma, the sense of its being alive was even stronger. Ron Lehman learned to sail on Nahma as a Sea Scout in the late 1940s, and the boat became part of his surrogate family. He felt he belonged to something bigger than himself when he was on the water with his mates, experiencing the exhilaration of speeding along in their trusted and true sailboat. So strong was his emotional attachment to Nahma that — over 70 years after he first sailed on the boat — he made a pilgrimage to Ottawa to see “the old girl” in person, and anoint her with holy water.

For Ken Jones, there was nothing better in the world than sailing Nahma.

Ken Jones’ nephew, Steven Mark Adams, also came to Ottawa to see Nahma. As a boy and a young man, he had sailed with his uncle and learned firsthand how special this boat was. He watched as Ken prepared it every spring for the new sailing season, using his well-honed boat building skills to repair any signs of wear and tear. When the work was done, they launched Nahma and spent countless hours out on the water marvelling at the speed and elegance of this elderly fish boat.

For Ken, there was nothing better in the world than sailing Nahma. However, when his health declined, he knew it was time to let his beloved boat enjoy a well-deserved retirement. Now both owner and vessel can rest peacefully, as Nahma has made its last voyage — into the Ingenium collection as a cherished part of Canadian history.

Just six months after retiring from her position as supervisor of the Collingwood Museum, my friend and colleague, Susan Warner, passed away in June 2020. Her loss was a poignant reminder of how artifacts connect us to one another, our history, and our communities.