A Phone Call from Below the Arctic Ice - The 50th Anniversary of Arctic III Sub-Igloo Phone Call to Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau

On December 17, 1972, Canadian scientists on an Arctic expedition made a groundbreaking phone call to Ottawa. The Arctic III expedition, led by Dr. Joe MacInnis, made the call from 12 metres (40 feet) below the Arctic ice in Resolute Bay, Nunavut, (which was, at that time, part of Northwest Territories).

The historic phone call connected the crew of southern scientists to their prime minister at the time Pierre Elliott Trudeau in Ottawa and required the use of many innovative Canadian technologies. These technological artifacts are now preserved in the national collection here at Ingenium and can be used to tell the story of this extraordinary call. The expedition’s crew of 15 scientists was interested in many different fields of underwater Arctic research. The fields of research ranged from marine biology to engineering to medicine, with some scientists specifically studying the problems that divers endured while working under water. This was the setting which allowed for the ingenious idea of making a call from below the Arctic ice. But, before even thinking of making phone calls, the crew needed to assemble an underwater work station, Sub-Igloo (described below).

To situate this story in Canadian history, we must first consider the larger historical and geographical context of the area where this took place. Nunavut means “our land” in Inuktitut and the Inuktitut name for Resolute: Qausuittuq, which means “the place with no dawn.” [1] [2] [3] It is the land of Inuit Nunangat, and the Inuit community living in the hamlet of Resolute were relocated there in the 1950s by the Canadian Government, making them the second northernmost community in Canada. As we will see below, more research is needed to add these voices to this particular history and to tell their story through our national collection.

Sub-Igloo (artifact no. 2014.0305) in storage at Ingenium's Collections Conservation Centre in Ottawa, Ontario.

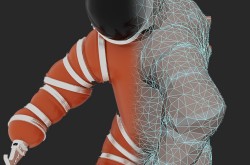

The central object in this history, the Sub-Igloo (artifact no. 2014.0305), was the world’s first diver- assembled polar dive station. Dr. MacInnis, a medical researcher, and Douglas Elsey, a professional engineer, invented, designed, and developed it in 1971. The dive station is an intriguing-looking artifact: large and round, the plexiglass sphere comes apart at a horizontal seam which is painted white. King Plastics Limited manufactured the two plexiglass domes in Mississauga, Ontario, and this prototype is the only Sub-Igloo that was ever made. The transparent work station provided a temporary work area for the divers on the Arctic III expedition. They could enter through the bottom of the work station, sit on the bench that wrapped the interior of the “room,” and take off their masks. Divers inside Sub-Igloo could see aquatic life swimming around outside while they extended the time they had to work in the near freezing water.

View into Sub-Igloo (artifact no. 2014.0305) showing the bench wrapping around the interior and the entrance at the bottom.

One crew member who was integral to making the phone call possible was Chester Beachell. Beachell was working as a Senior Research Officer in the Technical Research Division at the National Film Board of Canada when he took part in the expedition. Despite learning how to scuba-dive only three years before the expedition, at age 55, he had a passion for the sport and was also skilled at designing underwater sound recorders, also known as hydrophones. His role on the expedition was to set up underwater communication technology, sound recording equipment, and lighting. (The latter, a critical role as the expedition in Resolute took place in November and December, a time when there is no daylight!) A news article found in Beachell’s archival material includes a section about how Beachell came to set up the telephone connection:

“The idea of installing an actual telephone down below had not occurred to anyone until Ches Beachell was having a drink in the bar at Resolute on Cornwallis Island and got chatting with a technician working on the new Anik system to improve Arctic communications. “I’ll hook you up a phone in your operations tent so you can talk to anybody anywhere,” said the telephone man, “providing you’ll install the extension in Sub-Igloo.” [4]

Beachell followed through on his side of the deal and installed a red Contempra telephone (seen above and below) in the underwater station. The Contempra holds additional Canadian significance as the first Northern Electric telephone to be designed and built in Canada. Before this model, Northern Electric products were American designs. As for this specific Contempra, Beachell kept the telephone which made the historic phone call and it was later acquired by Ingenium (accession lot no. BF0004).

Red Contempra telephone (accession lot BF0004.002) that was installed in Sub-Igloo by Chester Beachell and was used to make the historic call to Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau on December 17th 1972.

As mentioned earlier, Beachell was working with a technician who was involved in work on the Anik Satellite. The Anik I satellite (also referred to as Anik A) was a first in its own right, Canada’s first domestic communications satellite on its launch on November 9th 1972, only a month before the phone call was made. You can find a 1/3 scale communications display model of the Anik A satellite (artifact no. 1987.0110) on display at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

Anik Satellite 1/3 engineering model (artifact no. 1987.0110)

Chester Beachell and the team working on Anik were not, however, the only ones responsible for this historic call. In fact, people across the country were involved in holding telephone line patches together to connect Ottawa and Resolute Bay. Beachell’s archival collection, which was also acquired by Ingenium, includes tapes that he recorded of the phone call and conversations that were happening before and after, both in Sub-Igloo and in the dive tent above them. These tapes reveal how the Arctic III members, Bell Telephone, and Canadian telephone switch operators worked together to make the call possible. The recording of the call to Prime Minister Trudeau was digitized and below is a section of that recording, available online for the first time.

In addition to Prime Minister Trudeau and Joe MacInnis, you will hear James (Jim) de B. Domville, a director from National Film Board who directed the film Sub-Igloo, as well as a telephone operator and an office worker in the prime minister's office. On the call, PM Trudeau can be heard faintly calling it “another great first for Canada” and it was, indeed, quite the feat, involving teams of Canadians using new innovative Canadian technology.

This is the sound recording of a phone call that was made to Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau from under the Arctic ice in Resolute Bay, Nunavut (at that time Northwest Territories), on December 17th 1972.

This video is bilingual (English and French).

Transcript

| Audio | Visual |

|---|---|

|

00:00 [Prime Minister’s Office] I’m getting you the Prime Minister Sir. [Dr. Joe MacInnis] Okay. [Prime Minister’s Office] Thank you. [The Right Honourable Pierre Elliot Trudeau, P.C.] Hello? [Prime Minister’s Office] Yes Mr. Trudeau? [The Right Honourable Pierre Elliot Trudeau, P.C.] Yes? [Prime Minister’s Office] Thank you, it’s long distance calling. 00:08 [MacInnis] Hello sir, how are you? [Trudeau] Hi Joe, how are you? [MacInnis] Just fine, gee, your voice is really clear and a let, let me tell you… [Trudeau] Are you under water, Joe? [MacInnis] Yeah, let me tell you where we are and what’s happening. I’m calling from Sub-Igloo and we’re in about forty feet of water - uh - beneath three feet of ice, temperature here in Resolute Bay is about forty-four, forty-five below zero. And of course, it’s uh, it’s uh black outside there’s no light. And uh - I’m sitting in the Sub-Igloo with Jim Domville. And – uh - the message, as far as I know, is going to a station just outside of Resolute Bay and then up to the satellite, which is in position above the equator, south of Calgary, and then back to a - a station near Toronto and then up to Ottawa. How’s that? 01:08 [Trudeau] That’s the Anik satellite? [MacInnis] Yes. [Trudeau] [undiscernible] [MacInnis] Yeah. [Trudeau] That’s great! [MacInnis] It’s just fabulous here and – uh - I sure wish you were here. You’d really enjoy, uh, uh, uh being here. There’s - there are shrimp/fis- swimming around outside. Uh we’ve got the four refuge stations just outside Sub-Igloo, the seashells, and – uh -we’ve got, now I guess, 160 dives or so behind us. And we’ll be coming back down in about a week’s time. [Trudeau] Joe, I hope we’ll be seeing you when you arrive to hear a bit more detail. [MacInnis] Well I, I, I sure would like to do that. And uh -look forward to – [Trudeau] Is there any difficulty in in clearing and equalizing when you get down in the colder water? [MacInnis] I think so. I think the colder water umm may cause a little more sinus problems and ear problems we’ve had uh sore throats and things up here but uh- [Trudeau] Ah. [MacInnis] - in this depth it hasn’t been too much of a difficulty. We sure had some problems – uh- getting set up down here. It took us probably a week longer than we figured because of - uh- some pretty sever winds and some pretty low temperatures. But - but once here, it just changes the whole perspective, the whole dimension. And now the biologists are working, the geologists are working and – uh - we’re testing equipment like the diver propulsion vehicle and frankly having a lot of fun too. 2:44 [Trudeau] Yeah, your, your igloo is at forty feet? [MacInnis] Yes. [Trudeau] Have you had any dives lower than that? [MacInnis] No, uh, we’ve stayed - uh - to about for - forty feet. Some of the guys have gone to fifty feet but we’re staying pretty close to the station because of safety reasons. [Trudeau] Right and – uh – you’re carrying lighting equipment or? [MacInnis] Yes, the National Film Board is here and, - uh - of course, Jim is with us for a couple of days and the film board brought some magnificent underwater lights. They put 1000 wats of light into the water. There’s one coming right overhead, right now as matter of fact. And – uh - Let me turn you over to Jim and he can describe – describe from his point of view. Here he is. 03:29 [Jim de B. Domville] Comment-ca va? [Trudeau] Oh, Bonjour Jim! [Domville] Je voulais quand même [muffled]. [Trudeau] Mais toi qui avais froid –

[Domville] [Rire] [Trudeau] - dans la mer – uh- des caraïbes. Tu va avoir plutôt froid dans le grand nord? [Domville] Oui j’ai froid – [Trudeau] [Laugh/rire] [Domville] Mais ça fait rien. [Trudeau] [Rire/laugh] [Domville] Non, on est, on est très bien équiper - [Trudeau] Oui. [Domville] Nous avons des - ce qu’on appelle des ‘Unisuits’ [Trudeau] Ah. [Domville] C’est une combinaison à l’épreuve [dans/durant de l’eau]. C’est [pas?] comme un [wet?] suit. [Muffled] – combinaison – uh - a l’eau. Et – uh maintenant je me sens parfaitement à l’aise ici mal fait l-le température. L- température de l’eau, ça fait à peu près vingt-huit degrés. 04:13 [Trudeau] [Je venir, je venir mais je envie --- ?]----- l’eau [Domville] Écoutez – écoute il faudrait que tu viennes en mois d’avril. Parce qu’ils vont faire [-----] si tous marchent bien, le quatrième dans la [séries], « Arctic Four », fin avril, début mai. Si [demande or on] avait/aller [----] de certains organismes au gouvernementaux, gouvernementale, - [rire] - mais il faut venir en mois de mai. [Trudeau] [muffled] [J’ai très envie d’aller] [Domville] Et je sais que c’est très facile de faire la plonger en question et [---] que je suis.

[Trudeau] [muffled laugh] [Domville] Et je te parle en français pour – uh - pour démontrer que il y a quand même le bilinguisme au-dessous de l’eau. A la quitté de soixante-quatorze [avril?]. [Trudeau] [Une unité bilangue?] [Domville] [Laughs] [Trudeau] Magnifique, et bien écoute- 05:11 [Trudeau] When you come down again [I was telling Joe,] I’d like to hear all about it. I hope when you come to Ottawa. [We could meet to discuss it.] [Domville] Love to. [Trudeau] Great. Great [achievement]. Getting some film over there, yuh? [Domville] Yes, uh we have got a crew here filming it for the NFB [Trudeau] Well another first for Canada. [Domville] Yes indeed. Let me toss you back to, uh, Joe. [Domville to MacInnis] Pierre just said “Another first for Canada.” 05:42 [MacInnis] It is a great, a great adventure and, uh, I’m only sorry that it’s almost over and I’m sorry that you couldn’t be here to dive with us. Maybe on one of the next ones. [Trudeau] Well if I were there I would hand you a little Canadian flag. [MacInnis] Laughs [Trudeau] And you would have handed me a [drowned out by Joe’s laughter] And we’d have a good laugh. [MacInnis] ha-ha yeah, touché. [Trudeau] Really a good achievement for Canada. [I bet its – uh - unique] [MacInnis] Yeah, it’s quite exciting, you know we’re sitting here, Jim and I and uh, uh there are no walls to see. Of course, they’re there; they’re made of that transparent plastic - uh that I - that we talked about and, uh, we can see the bottom, see the water column, see the lights above us and there are divers working and, uh, we can see the, uh, the two lights that indicate the holes that we made in the ice. 06:37 [Trudeau] [Muffled] [MacInnis] But it’s like no other diving and the thing that makes it, I guess uh, really exciting is that we’re pretty warm and comfortable. Getting an average of about fifty minutes per dive and this is because of the new suits and masks and breathing systems that we’re using so, uh, guys are staying pretty comfortable. [Trudeau] Is that the normal sized tank? [MacInnis] Yes, a lot of our dives have been made with the standard, uh, diving tank but we have this, uh, closed circuit breathing system that allows, well I guess 11 hours of uninterrupted breathing. We haven’t used it up to it’s full limit but we’ve used it up to 2 or 3 hours a day and uh it’s a major breakthrough because it means you don’t have to be rustling around with bottles and changing regulators and so on. But uh, perhaps when we get back we’ll give you a call and then… [Trudeau] I’d like to hear all about it, Joe. Very glad you called now [muffled words it’s really, uh, really, uh, significant - significant. Congratulations. [MacInnis] Well thank you sir, thank you very, very much. 07:49 |

Image of Sub Igloo in the centre of the video surrounded by a black background. Sub Igloo is an 8 foot wide plexiglass sphere. It is see-through with a bench about a quarter of the way up from the bottom. There is a white metal seem horizontally halfway up the sphere. At the very bottom there is a white metal grate made out of a semi circle. It is sitting on a wooden pallet and attached to the pallet by orange straps that loop through the metal along the mid-line. |

It is important to keep in mind that the nationalism that surrounds these “Canadian firsts,” and the Arctic Expeditions themselves, are a part of a colonial practice of southern scientists travelling on expeditions to the North. To this day, Inuit are critical of this colonial research done by southern scientists on such expeditions [5]. At the time of the Arctic III expedition, the Canadian government was interested in Arctic exploration as a part of establishing Canada’s sovereignty over the High Arctic.

One of Chester Beachell's hydrophones - Hydrophone No. 19 (accession lot BF0004.001).

It is evident in our records, such as in Beachell’s archival material that Inuit were involved in a number of expeditions. For example, in an article he wrote about Arctic III in National Geographic, Dr. MacInnis mentions Simon Idlout telling the expedition team stories. He states, “Obviously our friends to the North have much to teach us” [6]. On another expedition, this one to Alaska “In Search of the Bowhead Whale”, the team was accompanied by an Inuit guide, Homer Bodfish. During their search, Beachell shows two Inuit hunters his hydrophone which records under water sound. The unnamed Inuit hunters state that they already know the sounds they are hearing as belonging to the bearded seal and one says, “My people have heard it for 4000 years."

Map showing Resolute Bay in Nunavut.

Resolute Bay has its own dark colonial past due to the Inuit High Arctic Relocations which took place 20 years before the Arctic III expedition. The relocation project involved the Canadian Government forcibly relocating Inuit communities from Pond Inlet, North West Territories, and Inukjuak, Quebec, to Resolute Bay under false pretenses, giving them inadequate tools to survive the long winters of 24 hours of darkness. Additionally, they refused to follow through on their promise that if the families didn’t like the location they could return home. These relocations were due to concerns of Arctic sovereignty as well as a fear that the declining fur trade would lead to some Inuit requiring government assistance. More research is required so that we can tell a well-rounded story of how the community of Resolute Bay felt about Sub-Igloo, Arctic III, and similar expeditions up North.

To learn more about the experiences of the families that were relocated: The Qikiqtani Truth Commission published Community Histories of Resolute Bay from 1950-1975, which can be found on the Qikiqtani Truth Commission website at the following link:

https://www.qtcommission.ca/sites/default/files/community/community_histories_resolute_bay.pdf

References:

- Canada, Indigenous Peoples Atlas of, "Nunavut," Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada, [Online]. Available: https://indigenouspeoplesatlasofcanada.ca/article/nunavut/.

- M. Butcher, "Exploring Qausuittuq, Canada's Newest National Park," Canadian Geographic, 26 September 2016. [Online]. Available: https://canadiangeographic.ca/articles/exploring-qausuittuq-canadas-newest-national-park/. [Accessed 21 November 2022].

- "Resolute," Travel Nunavut, [Online]. Available: https://travelnunavut.ca/regions-of-nunavut/communities/resolute/. [Accessed 21 November 2022].

- J. Lee, Helping folks live better electrically beneath the arctic seas, 1972-1973?.

- P. Pfeifer, "An Inuit Critique of Canadian Arctic Research," Arctic Focus, 19 July 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.arcticfocus.org/stories/inuit-critique-canadian-arctic-research. [Accessed 9 December 2022].

- J. MacInnis, "Diving Beneath Arctic Ice," National Geographic, no. August 1973, pp. 256-267, 1973.