Who was first? Who was second? We do know. Third flight!

Bonjour / hi, my reading friend. Would you like to join me in remembering the 110th anniversary of the first controlled and sustained flight of a powered airplane within a group of territories known back then as the British Empire? This flight took place in the United Kingdom, in England to be more precise, in October 1908, and …What’s this I hear (read?)? The 110th anniversary of this first flight should be held in February 2019, to commemorate the flight made in Canada by John Alexander Douglas McCurdy? I respectfully beg to differ, my patriotic reading friend, and here lies a tale with several fascinating characters.

Let us begin this story with the individual whose achievements we are commemorating this week. Born in the Unites States in March 1867, Samuel Franklin Cody was in no way related to William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody, a somewhat better known individual. If truth be told, his name was actually Samuel Franklin Cowdery. Arguably the most colourful aviation pioneer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and probably one of the oldest, Cody was a kind, indomitable, generous, flamboyant and courageous individual. He arrived in the United Kingdom around June / July 1890 and soon became a well known Wild West showman. One of the places where he performed was a very popular entertainment destination in London, the Alexandra Palace or “Ally Pally” as it was commonly called.

As the years went by, Cody developed a keen interest in kites. The pioneering work done in Australia in the early to mid 1890s by Lawrence Hargrave, the inventor of the boxkite, was probably an inspiration. What began as a hobby financed by his performances gradually became Cody’s main occupation, if not an obsession. One more than one occasion, he had actually used his kite flying activities to publicise the aforementioned performances. In any event, by the late 1890s, several of the winged boxkites Cody had designed could lift without any difficulty a human being in a nacelle, or sitting on a chair. He approached the War Office, the ministry in charge of the British Army, in the fall of 1901 with the idea that kite trains could be used to survey battlefields. The latter showed little interest.

Eager to show the versatility of his invention, commonly known as the Cody kite, Cody conducted a number of meteorological flights in 1902. One of the kites reached an altitude of more than 4 250 metres (14 000 feet) – an astonishing performance if truth be told. Cody even crossed the Channel, from France to England, in a small boat towed by a kite, in November 1903.

Earlier that year, in March and April, Cody demonstrated his kites to Royal Navy officers who were quite impressed. Human observers lifted by kites could provide targeting information to the gunners of a warship. Kites could also be used to lift the aerials of the wireless telegraphy / radio sets under development for use ashore and on ships. The Royal Navy may have ordered a few kites at that time.

By 1905, the British Army was sufficiently intrigued by Cody’s achievements to give him a contract making him the kite instructor at the Balloon School of the Royal Engineers. In 1906, he became chief instructor and was given the task of designing and making kites at the Balloon Factory, the ancestor of the Royal Aircraft Establishment, an organisation mentioned in a September 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

And yes, there is a modern reproduction of a Cody kite in the formidable collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario. And yes again, my eagle eyed reading friend, this kite is from the collection acquired by the museum that yours truly mentioned in an October 2018 issue of our blog / newsletter / thingee.

In 1905, while on leave, Cody supervised the construction of a large biplane glider. Sent aloft as a kite, this easily demountable machine was set free by its pilot when it got high enough. Cody and several individuals, both military and civilian, test flew this glider before it was destroyed in a crash. Cody’s next project was an unpiloted powered kite completed in 1907. He tested it along the ground before suspending it from a cable mounted between two masts. The British Army seemingly forbade Cody from conducting free flights. If truth be told, Cody and the officers he had to deal with did not always get along. The rules and regulations of a tightly controlled organisation like the British Army could be as annoying to Cody as the latter’s very attitude and appearance could be to military personnel.

Another possible source of friction may have been the British Army’s lack of interest in powered airplanes. This service was by and large putting its money in airships, a type of flying machine which seemed to have a lot more to offer. Indeed, Cody had to put aside his work on the powered airplane he wanted to build to help with the construction of the British Army Dirigible No. 1 Nulli Secundus, the British Army’s first powered and piloted flying machine. Test flown in September 1907, this aerial giant flew to London in early October. Not too long after landing, the wind grew so violent that the envelope of Nulli Secundus had to be split to save it from destruction. Even so, the airship had suffered such damage that it never flew again.

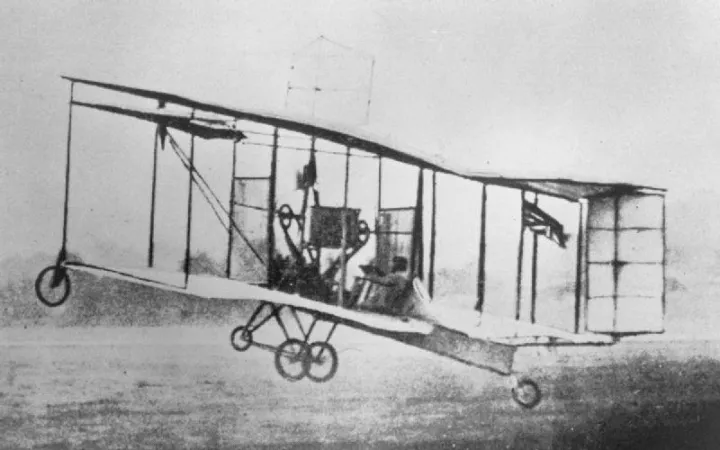

Cody was thus able to go back to his airplane, a single seat single engine biplane known as the British Army Aeroplane No. 1. A Royal Navy request to take part in kite trials caught him off guard. The flights took place between August and October 1908. They involved the use of human lifting kites. As intrigued as the Royal Navy was, its interest in kite flying soon faded away.

Cody made a few brief hops at the controls of the British Army Aeroplane No. 1 in September and October 1908. On 16 October, Cody covered a distance of about 425 metres (1 390 feet). This first controlled and sustained flight of a powered airplane within the British Empire ended somewhat abruptly. When Cody tried to turn to avoid a clump of trees, the tip of a wing touched the ground, which caused the airplane to crash.

Even though Cody supervised the construction of a virtually new airplane, completed around January 1909, the War Office terminated his contract in April. The British Army, it seemed, did not think that powered airplanes would be of great use. Cody was allowed to keep the airplane he had designed but the lack of resources hampered his efforts. Even so, he managed to make a number of significant flights in a few airplanes of his own design. Incidentally, Cody became a British subject in October 1909, during an aeronautical competition. His life, like that of too many aviation pioneers, did not end well. In August 1913, a seaplane Cody had designed broke up in mid air. He and his passenger fell out of the sky.

Given how Cody’s October 1908 flight ended, should it be added to the history books? Yes, it should be, my reading friend. In July 1909, when Louis Charles Joseph Blériot landed in England after completing the first airplane flight across the Channel, a turning point in the history of aviation if there was one, he damaged both the landing gear and propeller of his Blériot Type XI monoplane. Even so, he’s the one that history remembers.

In fact, do you know the name of the person who made the second airplane crossing of the Channel, in May 1910? Count Jacques Benjamin Marie de Lesseps was his name. Incidentally, this French pilot made the first major airplane flight in Canada, in July 1910, over Montréal, Québec – a 50 to 60 kilometre (about 30 to 35 miles) roundtrip that lasted 49 minutes. He was in town to take part in the Grande semaine d’aviation de Montréal, Canada’s first airshow, held in June and July. Indeed, de Lesseps was the star of the show. This natural showman was a son of Viscount Ferdinand Marie de Lesseps, the driving force behind the construction of the Suez Canal, in Egypt. He made his crossing of the Channel at the controls of a Bleriot Type XI nicknamed Le Scarabée (Beetle in English) – a name linked to his family’s past history in Egypt perhaps. Would you believe that de Lesseps was piloting that very airplane when he made his flight over Montréal? And no, there will be no pontificating on the Grande semaine d’aviation de Montréal, however tempting that may be.

Incidentally, the Egyptian god Khepri / Kheprer / Khephir / Khepera / Kheper / Chepri, who represented the rising / morning sun and, by extension, creation and the renewal of life, was associated with the dung beetle. The latter thus became one of the most famous insect gods in human history. The beetle in question has nothing to do with the ferocious and fictitious insects seen in the 1999 movie The Mummy.

How about McCurdy, you ask, my reading friend? If he was not the first person to make a controlled and sustained flight in a powered airplane within the British Empire, he was at least the first Canadian to do so. Well, actually, no. The individual who performed this feat was a friend of his, though. Frederick William “Casey” Baldwin flew about 97 metres (319 feet) at the controls of the first powered airplane developed by the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA), the Aerodrome No. 1 Red Wing, in March 1908, off the ice of a lake, near Hammondsport, New York.

The AEA, as you and I both know, was founded in October 1907. Its membership consisted of 2 Canadians, the aforementioned Baldwin and McCurdy, and 3 Americans, Lieutenant Thomas Etholen Selfridge, Glenn Hammond Curtiss and Alexander Graham Bell. And yes, my patriotic reading friend, Bell had become a naturalized American citizen in 1882. His American wife, Mabel Gardiner Hubbard Bell, although not officially a member of the AEA, played a significant role in the activities of the group. Incidentally, the airplane McCurdy flew on 23 February 1909, over the ice of Baddeck Bay, Nova Scotia, was the Aerodrome No. 4 Silver Dart, an airplane designed by him in the United States and made in that country by American workers using American tools and materials paid with American dollars. That American aerodrome, the word Bell used to describe an airplane, first flew in Hammondsport in December 1908.

What’s this, my slightly irritated reading friend? If McCurdy was not the first British subject (I must say I do not like that word.) to make a controlled and sustained flight in a powered airplane, then Baldwin must have been the one to do the deed. Well, sorry, but he was in fact preceded by a famous aviation pioneer, champion cyclist and race car driver by the name of Henry Farman, and…

I hear (read?) you, my reading friend, I hear (read?) you, but you’re mistaken. Farman was a British subject, until 1937 that is, when he became a French citizen, sometimes / often known as Henri Farman. He and his brothers Richard “Dick” and Maurice Farman were the sons of the well off Paris correspondent of an important London newspaper that still existed in 2018, The Daily Telegraph. The first controlled and sustained flight made by a British subject in a powered airplane occurred at Issy-les-Moulineaux, near Paris, in October 1907. The aforementioned Henry Farman was at the controls of the Voisin-Farman No. 1 biplane. This was only the beginning of a long and illustrious career.

So, what did McCurdy actually accomplish, you ask, my somewhat confused reading friend? Well, he was the third, yes, third (You do remember the title of this article, don’t you?) British subject to make a controlled and sustained flight in a powered airplane and the first one to do so within the group of territories known back then as the British Empire. And yes, McCurdy was the first person to make a controlled and sustained flight in a powered airplane in Canada. And no, yours truly does not believe that Louis “Lou” Gagnon, a travelling railway engineer, tested a steam-powered helicopter, the so-called flying steam shovel, in 1901 or early 1902, near Rossland, British Columbia. It’s a cool story but the evidence is somewhat lacking.

Incidentally, the first British subject to make a controlled and sustained flight in a British-made powered airplane in the British Empire was Edwin Alliott Verdon Roe, founder of A.V. Roe & Company Limited, one of the great aircraft manufacturing companies of the 20th century. He performed this deed in the Roe I Triplane, in July 1909. And yes, Avro, as the company was often called, founded A.V. Roe Canada Limited, one of the most famous Canadian aircraft manufacturing firms in history and one mentioned in a July 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. A replica of the Triplane, on display in the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester, England, as of 2018, was completed in 2009.

As you may remember, my reading friend, the centennial of powered flight in Canada was commemorated in February 2009, as it had been 50 years earlier, in February 1959, with a flight made with a replica of the Silver Dart. Incidentally, the replica of the Silver Dart flown in 1959 is one of the many flying machines in the amazing, all right, remarkable collection of the aforementioned Canada Aviation and Space Museum. Would you believe that British aviation enthusiasts completed a replica of the British Army Aeroplane No. 1 in 2008 to commemorate the centennial of the first controlled and sustained flight of a powered airplane in the United Kingdom? Interestingly enough, the expression British Empire was rarely (never?) used in conjunction with that project. And no, the replica was not flown. As of 2018, it was on display at the Farnborough Air Sciences Trust Museum, in Farnborough, England.

On this note, I bid you farewell, until next time.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)