Turning swords into ploughshares in the great state of Montana

You seem puzzled, my reading friend. Is the expression “water bomb” new to you? Fear not. Yours truly has an explanation. Our story, a sad story, began around 1925 with one of the most devastating forest fires in the history of the north-western United States. This crown blaze jumped uncontrollably from tree top to tree top. United States Forest Service teams paid a heavy price to bring this monster under control. Several men were injured and many mules used to carry equipment perished in the blaze.

The head of the fire control department of the United States Forest Service, Howard R. Flint, was devastated. Fighting a crown blaze from the ground made no sense, he thought. This type of forest fire had to be fought from above. Flint tried out his idea by dropping water-filled paper bags on burning trees from a low flying Curtiss JN-4 Jenny, a famous First World War training biplane. The trials were utterly unsuccessful. Using an unidentified fire suppressant to fill the bags did not provide much of an improvement. Accuracy remained abysmal and the bags contained too little material to have any impact on a fire anyway. And no, the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa, Ontario, does not have a Jenny. It has a Curtiss JN-4 Canuck, however, but I digress.

On at least two occasions during the 1930s, teams seemingly conducted trials with Ford Trimotor transport airplanes. They threw beer kegs full of water out of the airplane or dropped water from a tank of almost 400 litres (close to 85 Imperial gallons / 100 American gallons) in the cabin. These attempts made in Washington and Montana did not prove successful. The dropping of small “bombs” containing chemicals, in California, in 1937, did not prove any more successful.

As time went by, the United States Forest Service introduced specially-designed trucks that carried well trained mules as close as possible to a blaze. It also pioneered the use, in 1940, of highly trained parachutists, the famous smoke jumpers. As effective as these new ideas were, Flint remained convinced that aerial fire fighting could prove very useful.

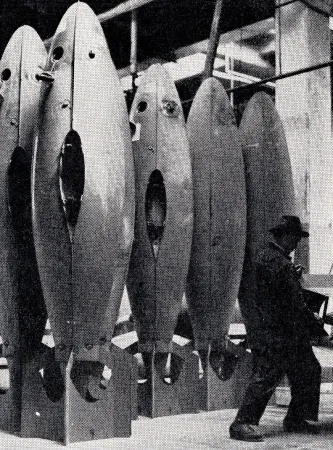

Soon after the end of the Second World War, Flint contacted high ranking officers of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF). Although surprised, these men had to admit that he might be on to something. Their bombers could accurately deliver the heavy loads needed to fight a small fire before it became an inferno. The USAAF readily provided the United States Forest Service with a number of droppable external fuel tanks, seemingly those designed for use on one of the most distinctive aircraft of the Second World War, the Lockheed P-38 Lightning twin-engined single seat fighter. Designed to contain approximately 625 or 1 180 litres (137 or 260 Imperial gallons / 165 or 312 American gallons) of gasoline, these tanks were soon fitted with bomb tail fins in order to improve the accuracy of the water drops. This work was done in a United States Forest Service machine shop. As this was taking place, Flint and his people were experimenting with various fire extinguishing liquids and mixtures.

The first water bombing trials took place in Florida, then Montana, in Flathead National Forest. At first, the water bombs were simply dropped on a fire started in a specific location. Flint was pleased with the results but suggested that bursting them over a fire would be more effective. USAAF officers again thought he might be on to something. They provided the United States Forest Service with a number of seemingly top secret devices, radio / radar operated proximity fuses if you must know, that would break open the water bombs at any desired height.

While one Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress four-engined heavy bomber was apparently used early on, the principal water bomb carrier was a Boeing B-29 Superfortress, a four engines heavy bomber and the most formidable aircraft of this type flown during the Second World War. This “Rocky Mountain Ranger” could carry up to 8 water bombs – or 184 small bombs filled with chemicals. Two Republic P-47 Thunderbolt single engined single seat fighter bombers carrying a pair of water bombs without proximity fuses were used to spot the fires and initiate the attack. The Superfortress would move in only if needed. Incidentally, you may remember that this type of bomber was mentioned in an article of our blog / bulletin / thingee published earlier in the month of February 2018.

After spending some time battling test fires in Flathead National Forest, the pilots of the Thunderbolts and the crew of the Superfortress went out to fight real blazes in the back country. The latter soon discovered that accurately dropping a load of water on a mountain side in very turbulent conditions was way more difficult than anything it had experienced during bombing raids on Japan. The trials went on for most of the summer of 1947. Although quite successful, they did not lead to the creation of an aerial forest fire fighting force, evaluated at 30 Superfortresses and 75 Thunderbolts. Perfecting the equipment would take time and cost a fair mount of money. The training of the crews and maintenance of the aircraft would also be costly. More importantly perhaps, as things turned out, the water bomb was not the best weapon for the job.

Aerial forest fire fighting as we know it today was to a large extent developed in Canada, from 1945 onward, by organisations like the Ontario Provincial Air Service, Field Aviation Company Limited, de Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited and Canadair Limited. But that, my disappointed reading friend, is another story.

More Stories by

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)