The wonderful little Meteorplane, the world’s first successful ultralight airplane?

Greetings, my reading friend. Yours truly must admit to some trepidation when the time came to prepare texts for the November 2018 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee. A couple of topics I held great hopes for did not pan out. As a result, I had to use 1 of the topics held in reserve for just such an occasion. This, of course, does not mean that today’s topic, found in the 18 November 1928 issue of the weekly Le Petit Journal, published in Montréal, Québec, is less captivating or entertaining than our usual fare. I have standards, you know. Still, you be the judge.

Our story began in California, in June 1892, when John Fulton “Jack” Irwin came into this world. From the looks of it, he was a bit of a wild boy with a strong interest in various mechanical implements. Irwin was not very good in school, however. Indeed, he left after completing Grade 4. From then on, the young boy spent pretty much all of his time tinkering.

Around 1904-05, Irwin saw an odd looking object in the sky. No, not an unidentified flying object. The flying machine in question was in all likelihood the California Arrow, a tiny single-seat non rigid airship / dirigible made by Thomas Scott “Tom / Captain Tom” Baldwin, a relatively unknown yet quite important aviation pioneer who should not confused with Frederick William “Casey” Baldwin, 1 of the 2 Canadian members of the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA). And yes, my reading friend, both “Casey” Baldwin and the AEA were mentioned in an October 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Back in the mid 1870s, “Tom” Baldwin had gradually gained fame as an aerial acrobat who wowed crowds by performing stunts from a trapeze bar suspended from a hot air balloon. As was to be expected, the public eventually grew tired of the death defying acts that he and others performed. Baldwin raised the ante by parachuting from hot air balloons. Indeed, this acrobat and accomplished tightrope walker pretty well launched this new stunt in the United States. Better yet, one could argue that Baldwin played a role in the development of the modern parachute. He seemingly made his first jump, from a gas balloon, in January 1887.

In July 1888, Baldwin made the first of several jumps in London, England, at / near the Alexandra Palace, a popular entertainment centre mentioned in a couple of October 2018 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee. As was the case in the United States, some people tried to prohibit parachute jumps, believing them to be far too dangerous. The ever larger crowds who flocked to the “Ally Pally,” up to 100 000 men, women and children it was said (written?), were not the least concerned. The Prince of Wales himself, in other words the future king Edward VII, born Albert Edward “Bertie” Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, went to see Baldwin jump. Assured the future of fairground parachuting in the United Kingdom was, if I may copy the speaking style of Yoda, the beloved Jedi master. Also assured was Baldwin’s reputation as one of the greatest aerial showmen in the world. As time went by, he made jumps on every continent except Antarctica, but back to our story. And yes, Edward VII’s mother, Victoria, was mentioned in another November 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Deeply impressed by the flights made in Paris from 1898 onward, in airships of his own design, by Alberto Santos Dumont, a wealthy and fearless Brazilian who lived there, Baldwin began to work on a flying machine of this type. Conscious of the limited capabilities of the tiny airship he had in mind, Baldwin looked for a light engine that could be mounted on it. He found one in the workshop of a young motorcycle maker and racing pilot. If truth be told, the sale of this engine was Glenn Hammond Curtiss’ first foray in the world of aviation. And yes, my knowledgeable reading friend, Curtiss later became a member of the AEA. He actually designed one of the powered airplanes made by the association, in his workshop to be more precise. As we both know, Curtiss was mentioned in an October 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Baldwin completed his airship, ambitiously named California Arrow, in August 1904. He seemingly tested it but, given his weight, may not have been on board when this was done. It is therefore possible that the California Arrow first went up without a pilot and with its engine stopped. Within days, Baldwin crated the engine and envelope, and took a train to St. Louis, Missouri. You see, my reading friend, this city was hosting a world fair, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, the most stupendous entertainment the world had ever seen, if I may paraphrase a newspaper headline of the time.

One of the many attractions of the world fair, besides the Games of the III Olympiad, was an aeronautical competition with a grand prize of no less than $ 100 000. To earn this truly titanic sum of money, a pilot only needed to go around a 16 kilometre (10 miles) circuit 3 times. Nothing to it. The individual favoured to win the grand prize was, you guessed it, Santos Dumont. In late June 1904, just after he arrived in St. Louis, the envelope of his airship, the No 7, seemingly known as the Coursier, was slashed beyond repair while stored in a hangar for the night. There would be no flight on 4 July, the American national holiday. The elite and media in St. Louis were beside themselves. Santos Dumont returned to Paris within days. The people responsible for this outrage were never identified. And yes, my sport loving reading friend, the Games of the III Olympiad were among the most ridiculous ever held – and this time, may I submit that you are the one who is digressing? Gotcha. Sorry.

With Santos Dumont conveniently out of the way, several American aeronauts launched attempts to win the grand prize. None of them made it past the 9 metre (30 feet) fence / barrier that surrounded the circuit. Hoping that someone would do better, the organisers of the competition indicated that participants had until the end of October to make their attempt. Baldwin arrived in St. Louis during the second week of September. He soon heard about an aeronaut, Professor Don Carlos, who was offering brief flights over the site of the world fair in a tethered balloon. The two men met. Don Carlos turned out to be the thin and light son of a respected newspaper publisher from Ohio, Augustus Roy Knabenshue. This unlikely daredevil agreed to help Baldwin win the grand prize. They attached the envelope and engine to a wooden frame made on the site of the world fair. Baldwin and Knabenshue may even have carved the airship’s propeller.

The California Arrow came out of its hangar on 25 October. Knabenshue started the engine. Fearing a problem, he yelled that a mechanic be found. Baldwin misheard his partner and ordered that the people who were holding down the airship let it fly freely. A somewhat surprised Knabenshue steered away from a hangar, got over the fence / barrier and moved away from the circuit. Before long, he was manoeuvring around the numerous palaces of the world fair. The tens of thousands of people on the fairgrounds watched in amazement; they cheered themselves hoarse. The engine of the California Arrow failed before long. Knabenshue drifted with the wind. He landed in a cornfield. Thus ended the first public flight of a powered flying machine in the Americas. If one is to believe newspaper reports, Knabenshue had covered a distance of almost 24 kilometres (about 15 miles) in 91 minutes. He and Baldwin instantly became national heroes.

Knabenshue delighted the crowd visiting the world fair until early November. He made turns, flew in circles and completed figure eights. As was to be expected, neither Baldwin nor Knabenshue won the grand prize. The former had to be satisfied with a sum of $ 500, no small change in 1904 but not the $ 100 000 he had dreamt of, for having proven that a flying machine could be manoeuvred.

Sadly, Baldwin and Knabenshue’s partnership did not last long. The latter returned to Ohio in the spring of 1905 and set out to make and fly tiny single seat powered airships derived from the California Arrow. The “King of the Air,” as Knabenshue liked to call himself, performed in numerous locations in the United States, making headlines wherever he went. Still too heavy to fly in his own airship(s), Baldwin hired a young man in his late teens. Lincoln J. Beachey would become famous both as an airship and airplane pilot. Ruined by the great earthquake that devastated San Francisco in April 1906, Baldwin temporarily joined forces with Curtiss. He also founded Baldwin Airship Company, in 1907. And no, my reading friend, yours truly will not be pontificating on what happened later on to these 4 fascinating people. Sorry.

This being said (typed?), it should be noted that, in September 1907, “Tom” Baldwin flew an airship, the California Arrow II, at the Nova Scotia Provincial Exhibition held in Halifax. In 1911, in the United States, he supervised the design and construction of the Red Devil III, a powered airplane similar to a Curtiss biplane whose fuselage was made of steel tubing – an innovative feature. The pilot of one of these Red Devils, as the other airplanes of this type were called, an American by the name of Lee Hammond, made the first flight over Canada’s capital, Ottawa, Ontario, in September 1911. In June 1914, during an airshow held in Montréal, Beachey completed the first loop the loop ever made in Canada. He was flying a Curtiss biplane at the time, but back to our story.

Irwin was fascinated to such an extent by the California Arrow that he spent a great deal of time at Baldwin’s camp. The aviation pioneer was touched (or annoyed?) by his enthusiasm and gave him a few odd jobs to keep him busy. Baldwin would not let Irwin fly, however.

Around 1905-06, Irwin heard / read about one or more parachute jumps that were to be made from a hot air balloon, not too far from where he lived. On the day he showed at the site, the parachutist was nowhere to be seen. The somewhat annoyed owner of the balloon was looking for someone brave (foolhardy?) enough to have a go at it. Irwin asked how much he paid. The sum offered for completing the jump ($ 10 or 20) being equivalent to what he could earn in a month, Irwin readily volunteered. He scrupulously followed the detailed instruction of the balloon’s owner and completed the jump without so much as a scratch. One has to wonder how Irwin’s parents reacted when he showed them the money later that day.

This first flight was a revelation for Irwin, though. Also around 1905-06, he began to put together a small airship with the help of some schoolmates. The boys “borrowed” bed sheets from a number of houses in the neighbourhood in order to stitch together the envelope of the tiny flying machine, in the basement of the Irwin family home. Irwin modified a bicycled frame to drive its propeller. When the airship was ready, he and his team moved it to the backyard of his parents’ home. Irwin secretly tapped into the house’s lighting gas / coal gas supply to fill the envelope. To his chagrin, his flying machine looked more like a squeezed lemon than an airship. Irwin later claimed that inflation of the airship took about 2 days, which begs the question of how this could be done without anyone noticing.

In any event, one fine day, Irwin sat on the bicycle seat, told his teammates to let go and began to pedal like mad. After rising high enough to clear a couple of fences, the airship was caught by the wind. It rose some more when it ran into a small column of warm air. The brief flight came to an end when the airship more or less gently plopped into the tress on a nearby hill. Delighted local journalists allegedly referred to Irwin as a boy genius. His parents may not have been quite as thrilled, especially when the gas bill arrived.

What’s this, my reading friend? You want to know what lighting gas / coal gas was / is? Well, at the risk of sounding pedantic, lighting gas was a lighter than air gas mixture produced from coal and used for lighting. Available in large volume during much of the late 19th and early 20th century, this highly flammable gas was far less expensive and much easier to obtain than another equally flammable lighter than air gas you may be more familiar with, namely hydrogen. The catch was that lighting gas provided a lot less lift than hydrogen.

While 30 cubic metres of cool air, the amount of air present in a small room perhaps, weighs an average of 36.75 kilogrammes, an identical volume of lighting gas weighs between 15 to 18 kilogrammes. In other words, 30 cubic metres of lighting gas would lift a balloon weighing between 18.75 and 21.75 kilogrammes. By comparison, 30 cubic metres of hydrogen would tip the scale at about 2.7 kilogrammes, which meant it could lift a balloon weighing 34.05 kilogrammes. When used in a balloon, lighting gas was barely better than hot air, a mixture of gases that weighed about 20.55 kilogrammes for 30 cubic metres when heated to a temperature of 65o Celsius. In other words, 30 cubic metres of hot air would lift a balloon weighing 16.2 kilogrammes. The limited lifting abilities of lighting gas explained why so many 19th century balloons were of gigantic size. They had to be very large indeed to lift their nacelle and passengers.

Given the possibility that you, my reading friend, may be metrically challenged, yours truly is pleased to provide Imperial equivalents to the figures quoted in the previous paragraph. While 1 000 cubic feet of cool air weighs an average of 76.5 pounds, an identical volume of lighting gas weighs between 31.2 and 37.5 pounds. In other words, 1 000 cubic feet of lighting gas would lift a balloon weighing between 39 and 45.3 pounds. By comparison, 1 000 cubic feet of hydrogen would tip the scale at about 5.6 pounds, which meant they could lift a balloon weighing 70.9 pounds. Hot air, on the other hand, weighs 42.8 pounds per 1 000 cubic feet when heated to a temperature of 150o Fahrenheit. This volume of hot air would lift a balloon weighing 33.7 pounds.

Interestingly enough, Irwin’s creation was by no means the world’s first human powered airship. Between May and July 1878, for example, an American inventor, Charles Francis Ritchel, and 2 young men tested a propeller-driven single seat vehicle of this type, both indoors and in the open air.

Irwin was not the only person inspired by the flights of the California Arrow. One only needs to think of Alva R. Reynolds. This Californian was so confident in the safety and simplicity of his brand new Man Angel, a tiny single seat airship powered by a pair of oars, that he allowed a 17 year old female, Hazel Odell, to fly it. She did so, brilliantly, in August 1905. Reynolds eventually built half a dozen Man Angels that he leased to fairs in a few states. He also opened an airship flying school. Reynolds stopped flying after a race (with an automobile?) during which one of his airships crashed in a treetop. Before too long, Reynolds and a relative, George A. Reynolds, developed a large device able to generate electricity from waves. Even though the California Wave Motor Company operated a demonstration plant for several months in early 1909, this fascinating project went nowhere.

In October 1907, a 15 year old American by the name of Cromwell Dixon won an international balloon race held in St. Louis. The “Boy Aeronaut” was flying his home-made single seat pedal powered airship, the Sky-Cycle. In June 1910, he flew a homemade powered airship at during the Grande semaine d’aviation de Montréal, Canada’s first air meet / airshow, held in late June and early July.

Would you believe that Baldwin himself completed a single seat aerial rowboat in 1905? Being too heavy to fly it, he hired a thin and light man to fulfil his contract with a California amusement park. Llewellyn Guy Mecklem entertained the crowd by dropping small bags of popcorn or peanuts, picking up a handkerchief he had dropped in mid air, or aiming his airship at a young woman in the grandstand – his favourite trick. The mischievous pilot would turn away from the increasingly distraught young person at the last second. Baldwin’s aerial rowboat was destroyed when the hydrogen in its envelope inexplicably caught fire one night. And yes, Ritchel, Reynolds, Mecklem, Dixon and the other pilots of oar powered airships were unable to control their flying machine if there was any wind. My apologies, I digress.

For his next trick, Irwin decided to leave lighter than air flying machines behind and go for a heavier than air machine, in other words an aeroplane / airplane. Like so many aviation pioneers before him, he built a glider. Completed around 1907-08, this biplane design may have looked a lot like one of the very well known airplanes made by Wilbur and Orville Wright. Irwin flew it on numerous occasions. In 1909, he lost control in mid air and crashed. He suffered a broken arm. The glider was destroyed.

Irwin’s family moved to another city in California around that time. Our young friend soon put together a 2-wheel vehicle with the help of a teenaged neighbour by the name of Paul “Pal” Conrad. Pal, as Irwin called his latest project, was powered by a small motorcycle engine that drove, no, not its rear wheel. The engine, say I, turned a propeller mounted at the rear, when it be could cajoled into working that is. Pal was a very noisy little machine. It may not have been very fast.

A turning point in Irwin’s life was his meeting with Homer and Ernest Brainerd, 2 brothers who ran a machine shop and foundry. Yours truly was not able to find out a precise date for this encounter but I have a feeling it may have taken place around 1908-10 at the latest. In any event, Irwin watched the brothers work and tried to make himself useful. The Breinerds soon began to show Irwin how to perform some jobs, simple ones at first. He was a good pupil and a highly motivated one. The Breinerds did not pay Irwin but he didn’t mind one bit. Irwin was learning something he could use to earn a living.

In 1912, Irwin completed a Curtiss type biplane using a set of plans he had acquired. He flew this machine, seemingly known as the Gray Eagle, in California and Nevada fairs / carnivals until 1914. Irwin may, I repeat may, have formed the John Fulton Irwin Company in 1912. He completed an airplane of his own design before the end of that year. Its modified automobile engine powered another original design completed between 1913 and 1915.

The next stage in Irwin’s adventurous life is a bit of mystery. He claimed he was one of the people who accompanied the 8 Curtiss JN-3 2-seat observation biplanes of the United States Army Signal Corps (USASC) sent to northern Mexico in March 1916 – the first combat operation of an American aerial unit equipped with airplanes. This seemed to indicate that Irwin had enlisted around 1915-16. What were these American airplanes doing in Mexico, you ask? A good question. Please note that what follows is not amusing at all. You see, my reading friend, close to 500 men led by Francisco “Pancho” Villa, born José Dorotheo Arango Arámbula, one of the most important players in the Mexican revolution, conducted a raid on Columbus, New Mexico, in March 1916. Fifteen Americans died in the attack, while about 70 Mexicans were captured or killed. Infuriated by this action, the administration led by President Thomas Woodrow Wilson ordered Brigadier General John Joseph “Black Jack” Pershing to lead an expedition into Mexico to pursue and disperse the raiders. The American public and media, on the other hand, very much wanted to see Villa punished – or killed.

Operating in a region with limited infrastructures, a harsh climate and mountain peaks that reached altitudes of up to 3 300 metres (about 10 800 feet), the JN-3s proved woefully inadequate. Within a month of their arrival in Mexico, only 2 of them were still airworthy. Worse still, these airplanes were so worn out that the personnel of the USASC squadron destroyed them before their return home in late April, to pick up new airplanes. The 12 observation biplanes that showed up in early May proved to be poorly constructed and unsafe to fly. The squadron received 25 or so additional airplanes of various types between the middle of 1916 and the spring of 1917. Seven of these were Curtiss JN-4s, a very well known 2-seat biplane commonly known as the Jenny.

The wooden propellers of the airplanes proved especially vulnerable to the hot and dry conditions encountered in Mexico. The head of the propeller making department of Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company went to Columbus with a couple of people to see what could be done to improve the situation. A mechanical engineer with a deep knowledge of propellers, Frank Walker Caldwell set up a small factory using local materials better suited to the local conditions. The propeller problem of the USASC was solved relatively quickly. Even so, the United States Army was sufficiently concerned to recommend to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the ancestor of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, that a thorough examination of materials used to make propellers be conducted.

Would you believe that Caldwell, by then chief engineer at Hamilton Standard Propeller Corporation, a division of United Aircraft Corporation, created the first hydraulically operated variable pitch propeller to reach production? This propeller, flight tested some time in 1931, insured the success of a new generation of American airliners, starting with the trend-setting Boeing Model 247. The potential importance of the new propeller was such that Hamilton Standard Propeller, through Caldwell, won the most coveted annual aviation award in the United States, the Collier Trophy, in 1933.

What is a variable pitch propeller, you ask, my reading friend? Well, if I may pontificate for a moment, a variable or controllable pitch propeller is one whose blades can be set at different angles in mid flight to give the best possible performance at any given speed. And yes, Hamilton Standard Propeller was mentioned in November 2017 and April 2018 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee. But back to our story, and to wooden propellers. And yes again, the stupendous collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa includes a Model 247, and a lot of propellers, but I digress. Yet again, but I’m not sorry.

When the United States joined the United Kingdom, France and their allies, including Canada, in their struggle against the German Empire and its allies, in April 1917, the need to produce huge numbers of propellers as quickly as possible meant that wood remained the material of choice.

Even though the USASC squadron did not return to Mexico, it did keep a few airplanes there, on rotation, until the withdrawal of Pershing’s punitive expedition in early February 1917. And yes, my astute reading friend, the Curtiss JN-4 Canuck made by Canadian Aeroplanes Limited of Toronto, Ontario, in 1917-18 was / is a derivative of the aforementioned JN-3.

While it succeeded in defeating and dispersing the force responsible for the raid on Columbus, the punitive expedition failed to capture the wily Villa. Worse still, by late 1917, early 1918, the latter had managed to build up a powerful force under his command, but that’s another story.

When the United States entered the First World War, Irwin tried to qualify as a pilot. A temporary paralysis of his right arm, the result of a recent accident, meant that he failed to do so. When he got better, Irwin was hired by the USASC as a civilian instructor. Later on, he flight tested rebuilt fighter airplanes. This work on American soil seemingly continued until the end of the First World War.

Very much aware that this conflict would not last forever, Irwin began to think about what he would do when peace returned. He believed that many military pilots would want to keep on flying. They would undoubtedly be interested in acquiring a small and inexpensive airplane that would be fun to fly. Irwin was convinced he could design such an airplane. Finding a suitable engine for it would be the tricky part. By the middle of 1919, Irwin had a complete set of plans. Construction of a prototype began, in the small workshop of Irwin Aircraft Company, a company founded at some point in 1919. Irwin used a motorcycle engine to power his biplane. The M-T Meteorplane flew for the first time in July or August 1919. Its flying characteristics were said to be very good.

As proud as he was of his creation, Irwin felt before it even flew that a motorcycle engine was not the way to go. Unable to find what he was looking for, he set out to design an engine. The Irwin Engine or Meteormotor, as Irwin eventually called it, had some issues when first tested but a little bit of tweaking turned it into a very reliable engine. Over the years, Irwin Aircraft completed 75 to 80 of these.

Irwin Aircraft began to sell plans and kits of its first production airplane, the M-T-1 Meteorplane, in 1922. No one knows how many kits were sold, or how many airplanes actually flew. It looks as if Irwin’s customers had the option to buy individual parts of a kit, if money was tight. The Meteorplane was one of the first, if not the first airplane available in kits to hit the market after the First World War. An unusual / innovative feature of the airplane was (were?) the strong plywood struts that linked the upper and lower wings. Moving the struts and wings a little bit forward or back allowed our homebuilder friends to account for the weight of various types of engines. And yes, my reading friend, homebuilding has been mentioned in several issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since November 2017.

Do you have a question? Do we know the identity of the first airplane designed for kit construction by homebuilders? A good question. This machine may, I repeat may, have been the Baby White or Baby White Monoplane. Designed no later than 1916-17 by George D. White, this tiny American monoplane was powered by a motorcycle engine fitted with a chain-drive. White ran ads for his airplane in a number of issues of Aerial Age Weekly in 1917 and 1918, and managed to sell a number of kits to enthusiasts before going out of business. This gentleman should not be confused with a contemporary of his, Sir George White, the chairperson of a British firm, Bristol Tramways & Carriage Company, and founder of one of the great aircraft makers of the 20th century, Bristol and Colonial Aeroplane Company, later known as Bristol Aeroplane Company. Now that your curiosity is satisfied, at least for now, let us go back to the topic at hand. And yes, you are correct, my reading friend, Bristol Tramways & Carriage was mentioned in an October 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Understandably enough, the Meteorplane attracted a fair amount of attention and good publicity, both in the United States and overseas, when it came out. As the sales of plans and kits increased, Irwin was able to buy tooling to produce the Meteormotor. Unable to find tires and wheels that would fit his airplane, he also bought tooling to produce these items.

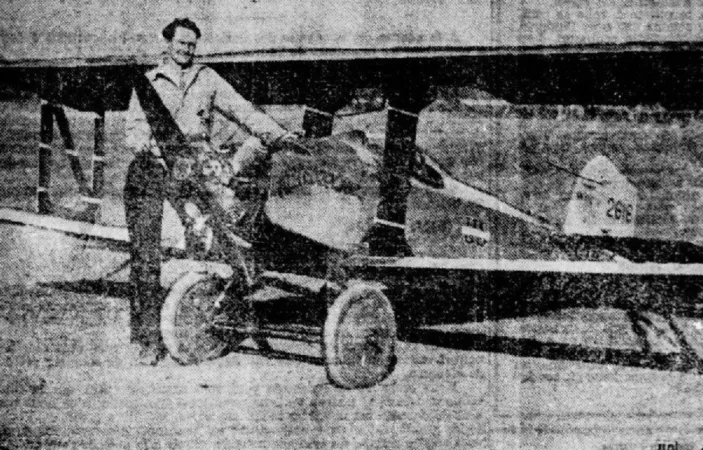

A second version of the Meteorplane, the M-T-2, went into production around 1926. An example of this machine can be seen in the photo at the beginning of this article. Irwin Aircraft built approximately 40 M-T-2s. The company allegedly sold a few hundred kits and a few thousand sets of plans. No one knows how many airplanes were actually completed and / or flown. Irwin claimed that a then unknown Charles Augustus Lindbergh paid him a visit in the spring of 1927. And yes, the “Lone Eagle,” as he was often called, was mentioned in a September 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Confident in the capabilities of the M-T-2, Irwin took part in an aerial tournament and aviation ball, the first of several such annual events perhaps, held in Visalia, California, in June 1927. He earned more points for speed and efficiency than pilots who flew airplanes powered by engines 4.5 to 10 times more powerful. Would you believe that Irwin’s airplane consumed a measly 5.9 litres per 100 kilometres (48 miles per Imperial gallon / 40 miles per American gallon)? Can your 21st century automobile beat that, my reading friend? By the way, I hear (read?) that famous movie actor Kevin Michael Costner lived in Visalia during his youth.

In September 1927, Irwin drove to Spokane, Washington, to take part in the National Air Races or, more specifically, the National Air Derby. He had with him a small racing version of the M-T-2. This machine caused quite a sensation, even among pilots. None of them had ever seen such a tiny flying machine. The day before the race Irwin wanted to compete in, a wheel broke off on take off when it hit a small hole. Even though the damage sustained during this aborted test flight was relatively minor, Irwin did not have enough time to make repairs. He could only watch as another pilot, one of the fathers of the homebuilt movement in North America, won the light / ultralight airplane race.

Edward Bayard “Ed” Heath was a gifted mechanic and largely self-taught airplane designer who had been involved in aviation since 1909. The young man’s first airplane, based on a monoplane designed by Louis Charles Joseph Blériot, presumably the Type XI, flew numerous times before hitting a fence, in 1910. And yes, my slightly annoyed reading friend, this great aviation pioneer was mentioned in an October 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, as was the Type XI. Faced with having to pay for repairs, Heath got a job with a company founded by the aforementioned Curtiss, quite possibly G.H. Curtiss Manufacturing Company, a motorcycle manufacturer. He formed E.B. Heath Aerial Vehicle Company around 1913-14 to provide aviation enthusiasts with ready to fly, if engineless, copies of several types of French, British and American airplanes, including Curtiss biplanes. These kits were among the firsts offered in North America.

Like many others, Heath dreamt of creating an airplane so simple and cheap that almost anyone would be able to buy and fly it. With the help of an aeronautical engineer named Claire Linstead, he designed a small single seat monoplane racer, the Humming Bird, soon renamed the Tomboy, which took part in the 1926 National Air Races. Heath won a race. The prize money was used to design a small single-seat parasol monoplane. To cut cost and accelerate work, Heath and Linstead apparently used the lower wing of a Thomas-Morse S-4 Scout, or “Tommy,” a single-seat biplane fighter airplane used by the USASC during the First World War for the advanced training of pilots. Heath brought his airplane to the marketplace in 1926. A refined version known as the Heath Parasol, flown in 1927, gained immediate attention throughout North America.

Hundreds, if not thousands of Parasols were built in houses, garages and barns. It is said one was even built in a church. At least 30 Parasols were completed in all provinces of Canada but New Brunswick between 1929 and 1941. Interestingly enough, a Parasol built in the fishing village of River John, Nova Scotia, by D. MacKay “Kay” Ross, remained on the Canadian civil aircraft register until 1968, but back to our story. Sort of. Did I forget to mention that the rebuilt fighter airplanes that Irwin test flew in 1917-18 were Thomas-Morse S-4 Scouts? Sorry. Small world, isn’t it? And no, Newfoundland was not part of Canada in 1941.

A kit airplane came to North America before the Meteorplane and the Parasol courtesy of, you guessed it, Santos-Dumont. Wow, you are smart. To quote the evil Asgardian Loki Laufeysson in the 2013 movie Thor: The Dark World, I’m impressed. In early March 1909, this gentleman, Santos-Dumont that is, not the other guy, test flew what was arguably the first successful ultralight airplane. Although easy to build, the No. 20 Demoiselle could be tricky to fly. In order to encourage the development of aviation, Santos-Dumont made the plans of his airplane available to anyone interested in building one. European amateur builders constructed most of the Demoiselles put together before the First World War. Although a Canadian-made airplane of this type has yet to be identified, the design probed somewhat popular in the United States, possibly as a result of a 2-part article published in the June and July 1910 issues of a well known monthly magazine that still existed in 2018, Popular Mechanics, but I digress. Again. Sorry. And yes, Loki was mentioned in a November 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

If I may be permitted to digress for a moment, the Asgard were a benevolent if slightly anal alien species present in numerous episodes of the Canadian American / American Canadian military science fiction television series Stargate SG-1, broadcasted between 1997 and 2007. This being said (typed?), the Asgard known as Thor did not look one tiny bit like the actor who plays this character in the well known eponymous movie series. And yes, Christopher “Chris” Hemsworth was mentioned in the aforementioned November 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

The C-C-1 Meteorplane and the C-C-2 Meteorplane were improved and slightly more expensive versions of the M-T-2. Introduced in 1928, they were designed to meet the needs of sportspeople who wanted to cover longer distances without having to land as often to refuel. Irwin Aircraft built 10 or so airplanes of these types. It tried to have the F-A-1, a 1930 derivative of the C-C-1 / -2, certified by the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) but the cost of this endeavour proved so high that the process could not be completed. And yes, the CAA was mentioned in a July 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Irwin Aircraft’s fortunes took a turn for the worse in 1930 when its founder was hit by a motorcycle. Irwin’s legs and arms were broken. He spent 18 months in hospital. With Irwin gone, airplane production continued for a few weeks or months but eventually came to a stop. Irwin Aircraft even had to cancel orders and return any money sent in as deposits. The company later went out of business. When Irwin finally left the hospital, he chose to manage the airport of a California town as well as the repair shop located nearby. As the years went by, Irwin completed a few more Meteorplanes but kept one he had used as a demonstrator. He put this airplane in storage when he went to work as a civilian instructor for the United States Navy after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, in December 1941. One day, individuals vandalised Irwin’s Meteorplane and stole its Meteormotor.

Irwin took the remains of the Meteorplane to his home around 1955. He and his wife Ethel set out to restore it. After much sleuthing, Irwin found the missing Meteormotor, which was being used as water pump. He actually had to buy it back from its current owner. All in all, Irwin and his wife worked on the Meteorplane for a good 18 years. He donated the airplane to the Oakland Museum of California, in Oakland, California, around 1974.

The only other Meteorplane left in the world is stored in pieces at the Port Townsend Aero Museum of Chimacum, Washington.

Irwin died in February 1977. He was 84 years old.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)