“My diploma, I have it.”: Gaby Morlay, symbol of the free Frenchwoman of the roaring 20s and first female airship pilot in the world

Hello, my reading friend, hello. Yours truly must confess that it is with a pleasure barely contained that I offer you this article. I am indeed fascinated by the flying cetaceans that airships were / are. Wishing to be brief, I will not make you wait any longer.

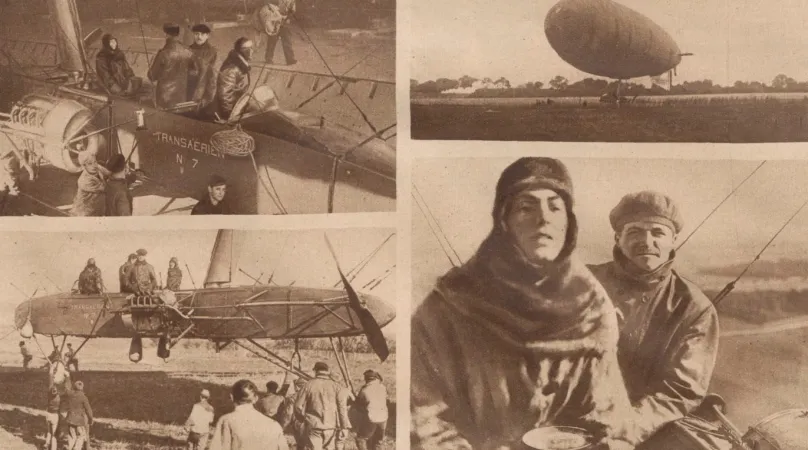

You obviously remember that Le Miroir, of which yours truly used the photographs above, taken from the issue published on 26 October 1919, was the illustrated supplement of the great French daily Le Petit Parisien, and ... That doesn’t ring a bell at all, now does it? Sigh. Let’s move on.

Our story began in June 1893 with the birth, in the land of France, the land of my ancestors, of Blanche Pauline Fumoleau. Enraptured by freedom, she fled the convent where her parents had placed her and went to Paris. The teenager hoped to become a typist.

One evening, while attending a show, Fumoleau laughed to such an extent, a sharp and exuberant laugh, that a couple sitting nearby kindly / seriously proposed that she work in the theatre. Why not, she said? As long as one got paid. Fumoleau went up on scene after a short apprenticeship, around 1909. She was not yet 16 years old. Since her name did not roll off the tongue, the teenager received a stage name, Gaby de Morlaix, which eventually becomes Gaby Morlay. De Morlaix / Morlay soon pleased the Parisian public. In fact, she enchanted it.

Passionate about the theatre, the young woman worked in the cinema no later than 1914, however, to ensure her subsistence. Her triumph in a talking film, in 1930, was a turning point. From that moment, Morlay took the cinema much more seriously. In fact, she became one of the biggest stars of French cinema, and this despite a voice which was a tad slender.

What can one say about this popular, spiritual and talented actress from which emanated an intense joie de vivre? Morlay was a tiny little woman with sparkling eyes who, during a career that spanned more than half a century, played in about 110 silent and talking films and an indeterminate number (40? 45?? 50???) of theatre plays. This authentic actress was as successful in dramas as in comedies. Whatever project she worked on, Morlay was vivacious, spontaneous, skilled, serious, reactive, powerful, intuitive, harmonious, deep, curious and adaptable.

In her daily life, Morlay was the symbol of the free Frenchwoman of the roaring 20s, the 1920s caught between the slaughter of the Great War and the chaos of the Great Depression. This pioneering non-conformist woman loved to move and innovate. She loved sports, and not just as a spectator. A good rider and swimmer, Morlay also boxed and skated. In 1920, for example, she participated in the 13th edition of the swim across Paris.

Morlay was interested in virtually all sports related to motorised means of transportation: airplane, airship, automobile and scooter. Still in 1920, she enrolled in the first motor scooter / motor kick scooter contest held in Paris, organised by a well-known Parisian sports daily, L’Auto. Feeling unwell on the day of the competition, Morlay could not participate, and ... What is it, my reading friend, you seem a tad perplexed. What was / is a motor scooter / motor kick scooter, you ask? Profuse apologies. These terms then referred to vehicles known today as scooters.

Interestingly enough, at least for yours truly, a digression enthusiast as you know painfully well, Morlay planned to participate in the aforementioned competition with a British motor scooter, more specifically an A.B.C. / Campling Skootamota. If this distant cousin of the Innocenti Lambretta and Piaggio Vespa, 2 vehicles mentioned in an August 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, appeared to be manufactured and sold by Gilbert Campling Limited, it was marketed by A.B.C. Motors (1920) Limited. And that’s where the story became interesting from an aerospace point of view, a detail that allows me to link our topic of the week to the wonderful Canada Aviation and Space Museum of Ottawa, Ontario.

Yes, yes, the fact that the Skootamota was / is a mode of ground transportation also allows me to link our topic of the week to a sister / brother institution of the breathtaking Canada Aviation and Space Museum, the Canada Science and Technology Museum, in Ottawa.

What was / is really interesting here, however, was the fact that A.B.C. Motors Limited, the firm which preceded A.B.C. Motors (1920), developed, in 1917-18, one of the first, if not the first air-cooled, high-power radial engine for aircraft. The British government signed contracts with 17 or 18 companies that made provision for the manufacture of 11 930 examples of said engine. These were destined to be mounted on a good part, if not the majority of the combat aircraft that the British air force, or Royal Air Force (RAF), anticipated / hoped to receive in 1918-19.

The fly in the ointment, if I may use this expression, was / is that this A.B.C. Dragonfly was / is one of the worst aircraft engines of the 20th century. While the first tests proved to be quite successful, the Dragonfly was nevertheless heavier and less powerful than expected. Subsequent tests showed that this engine vibrated to such an extent that it threatened to self-destruct after just a few hours of operation. Approximately 1 150 examples of this mechanical abomination left factory floors before the cancellation of the production program, in 1918. The number of Dragonflys tested in the sky could apparently be counted on the fingers of the 2 hands of a typical human being, or monkey. Hello, cousin!

Dare I say that the RAF could count itself lucky that the Armistice which ended the fighting of the First World War was signed in November 1918? Uh, yes, I dare. If I may be permitted a comment, an excellent salesperson and a somewhat gullible buyer were / are not always a good combination. But back to the great French actress at the heart of this article.

Fascinated by aviation like millions of other Frenchwomen and Frenchmen, Morlay wanted to pilot a balloon. The beginning of the First World War, in 1914, put an end to her hopes, but this was but a postponement. Indeed, by July 1920 at the latest, Morlay had an airplane pilot’s license, a balloon pilot’s license, and an airship’s pilot’s license, obtained in an order that was not necessarily the one in which they were mentioned here. The French actress was / is in all likelihood the first woman in the world, and one of the first human beings, to hold these 3 types of licenses.

In 1919, Morlay discussed the possibility of obtaining her airplane pilot’s license with the first woman in the world to obtain said license, in March 1910, Élisa Léontine Deroche, better known under the invented pseudonym of baroness Raymonde de Laroche. The death of the latter, in July 1919, in an airplane crash, deeply saddened Morlay but did not change her mind.

Would you have a few minutes to devote to a peroration on the airship pilot training undergone by Morlaix, my reading friend? Yes? Wunberbar! Know then that her instructor was a pilot and engineer well known in the French aeronautical community for his many ascents and test flights, made for his employer, the Société française des ballons dirigeables et d’aviation. This being said (typed?), Pierre Debroutelle played in all likelihood an equally important role in nautical sports and maritime rescue. You see, he completed a pneumatic / inflatable boat in 1934, or 1937.

An improved version, tested in 1940, was / is the ancestor of the Zodiac inflatable boats used after the Second World War by the armed forces of several / many countries as well as by countless water sports enthusiasts all over the world. The team of the famous French oceanographer, inventor, filmmaker, environmentalist and author Jacques-Yves Cousteau used loads of Zodiacs during his expeditions, for example. Long live the Earth! We do not have another one. And yes, this gentleman was mentioned in January and April 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, but back to our story.

A detail before going there. Zodiac Nautic Société par actions simplifiée, a subsidiary of the French firm Energetic Développement Société anonyme à responsabilité limitée specialising in the design, manufacture and marketing of inflatable boats, still existed as of 2019, but I digress.

The airship on which Morlay underwent her training in 1919 was in all likelihood in service during the First World War. It also served in all likelihood with an anti-submarine unit of the Marine nationale, the French navy. Its manufacturer was the aforementioned Société française des ballons dirigeables et d’aviation.

In late 1919, said airship belonged to the Compagnie générale transaérienne, an air carrier whose acronym, CGT, should not be confused with that of the Confédération générale du travail, a very important French central labour body mentioned in an August 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Would you believe that one of the founders of this company which used aerostats and aircraft, in other words airships and airplanes, was none other than Henry Deutsch de la Meurthe, born Salomon Henry Deutsch, a French industrialist / entrepreneur, patron and composer mentioned in the same August 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee?

You may remember, my reading friend with an elephantine memory, that in late August 1919, the British air carrier Aircraft Transport & Travel Limited launched the first scheduled international air service between the United Kingdom and France. This being said (typed?), did you know that this firm mentioned in a September 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee made the liaison in collaboration with the Compagnie générale transaérienne? Ours is a very small world, is not it?

Morlay obtained her airship pilot’s license in November 1919. According to a French newspaper, her success gave an American actress named Lillian Sisson (spelling?) the idea of doing the same. Yours truly must admit that I have not found any article about this young woman, or her project, in the American press of the time.

Morlay did not seem to have flown a lot after obtaining said airship pilot’s license. This being said (typed?), she apparently bought a gas balloon in 1920. In October of that year, during a major airshow, she participated, as a passenger, in a balloon rally. The aeronaut and author Roger Lallier counted among the pilots who took off in pursuit of the balloon piloted by count Henry de La Vaulx. The third crew member of Lallier’s aerostat was an American actor, choreographer and dancer named Harry Pilcer. This was his first flight.

Would you believe that de La Vaulx was one of the founders of the 2 companies that gave birth to the Société française des ballons dirigeables et d’aviation? Ours is a very small world indeed, is not it?

In fact, you probably wonder if, like the famous Captain Jack Sparrow, a gentleman (?) mentioned in a September 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, yours truly plans it all, or just makes it up as I go along. You decide.

If Morlay made about 15 films throughout the period during which France was occupied by the armed forces of National Socialist Germany, she specified, once her country was freed, that she had never worked for Continental Films Société anonyme, a major film production company under French law but with German capital founded towards the end of 1940. A shadow hovered briefly over Morlay, however, especially since many important people in Paris knew that she had / was having an affair with Max Bonnafous, the love of her life and the poorly married Ministre secrétaire d’État à l’Agriculture et au Ravitaillement (April 1942 – January 1944) in the collaborationist government led by Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain during the dark period that the Occupation was.

Prosecuted for his role during the Second World War, Bonnafous obtained a voluntary dismissal in 1948, the judge having decided that the evidence gathered against him did not justify the continuation of said prosecution. The services he had rendered to the Résistance and his polite but tenacious resistance to the demands of the German occupation authorities forces were also recognised.

Morlay and Bonnafous remained close until the death of the latter’s wife, in 1961. The friends / lovers got married soon after. Morlay died in July 1964, at the age of 71, shortly after completing a film and a theatre play. Her star still shines in the firmament of French, European and world cinema.

Peace and long life, my reading friend.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)