3 Things you should know about how a beloved Christmas tradition got its start in the Cold War, how researchers use science to improve traditional recipes, and how the cold you feel in winter doesn't actually exist

Meet Renée-Claude Goulet, Erin Gregory, and Michelle Campbell Mekarski.

Renée-Claude is Science Advisor at the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum, Erin is Ingenium’s Curator of Aviation and Space, and Michelle is Science Advisor at the Canada Science and Technology Museum.

In this colourful monthly blog series, experts at Ingenium and occasional guest writers offer up interesting and sometimes quirky nuggets related to their areas of expertise. For this December edition, Erin fills in for the Canada Aviation and Space Museum’s usual contributor, Science Advisor Cassandra Marion. This month’s three experts discuss how a beloved Christmas tradition got its start in the Cold War, how researchers use science to improve traditional recipes, and how the cold you feel in winter is actually an illusion.

The Cold War Roots of a Beloved Christmas Tradition

The North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) was established in 1958 during the Cold War. It was a joint-defence effort to protect Canada and the United States from airborne threats launched by the former Soviet Union. The agreement is still in place today and NORAD is charged with monitoring threats from air, space, and, more recently, sea, to the safety and security of the Canadian and American peoples. This a round-the-clock job, 365 days a year.

But every year on Christmas Eve, NORAD takes on an extra special task – tracking Santa Claus as he flies around the world delivering presents! This now-beloved tradition began at a very unlikely moment, at the height of Cold War tensions.

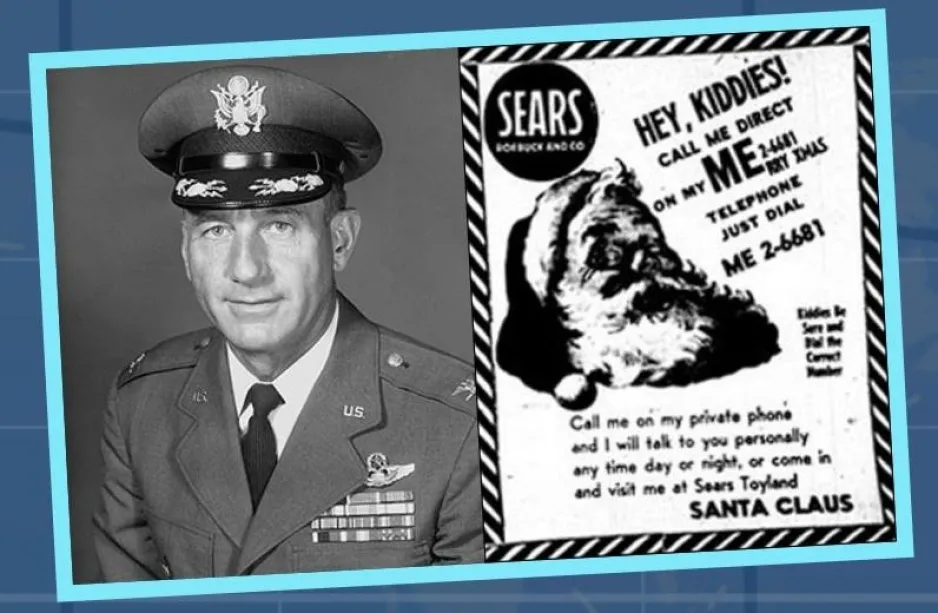

Photo of Colonel Harry Shoup next to the Sears ad with the typo that led to the NORAD Tracks Santa Christmas Eve tradition.

In December 1955 at the Colorado Springs Headquarters of NORAD’s predecessor, the Continental Air Defense Command (CONAD), the day started out like any other. That is until the red phone rang. This phone was a top-secret line and was to be used only in the event of a real national emergency, so all eyes in the Control Center were on the commander, Colonel Harry Shoup, as he answered the phone.

It’s hard to imagine what Col. Shoup was expecting to hear, but it certainly wasn’t a little voice asking “Is this Santa Claus?” Assuming this was a prank, an unimpressed Shoup barked “Is this a joke?” He surveyed the room, looking for indications from his staff that they were in on it. Seeing none, he barked at the caller once again, “Just what do you think you are doing?” That was met by the sound of a crying child on the other end of the line.

Changing course, Col. Shoup ho-ho-ho-ed and replied that he was indeed Santa Claus – much to the surprise of his staff. He listened to the child’s Christmas wish list and then asked to speak to the child’s mother. She explained that her child called the number for Santa Claus that was printed in a Sears Roebuck ad that had run in the local paper that day.

While the ad clearly stated that kids calling the phone number should be sure to get the number right, the copy editors did not follow that same advice. A simple typo led to a flurry of Santa calls right to one of the nation’s most secret phone lines!

While the Colonel worked to get a new phone number set up for the red phone, he instructed a few airmen to answer whatever calls came in for Santa. This was very out of character for someone like Shoup, who was known to as a no-nonsense, by-the-book, career airman. But something – perhaps the Christmas spirit?! – had gotten into him that season.

On Christmas Eve, Col. Shoup arrived at the Control Centre to find something strange on the large plexiglass board that airmen and airwomen used to track airborne objects sighted by radar. It was an image of Santa Claus in his sleigh pulled by reindeer coming from the North Pole! His staff explained that it was a joke and offered to take it down. But Col. Shoup had a better idea. He asked for CONAD’s community relations officer and, before long, the Colonel was on the phone with a local radio station reporting that CONAD has spotted a sleigh-shaped object on radar, coming from the direction of the North Pole. More stations got into it and began calling for updates on Santa’s location.

An image of one of many Facebook updates from NORAD Tracks Santa on Christmas Eve in 2022. This “Santa Cam” shot shows the big guy in his reindeer-drawn sleigh flying over NORAD Headquarters.

What started out as a typo and a joke became a feel-good mission and a beloved tradition that is now nearly 70 years old. NORAD tracks Santa and reports his location using all the tools at its disposal, including satellites, radar, fighter jets, and Santa cams. It is easier than ever to find out where the big guy in the red suit is on Christmas Eve through NORAD’s website, social media accounts, apps, and, as tradition would have it, by phone. Even devices like Alexa can report Santa’s location!

If you celebrate this season, be sure to check in with NORAD so you know when jolly Old St. Nick will be in your neck of the woods!

By Erin Gregory

Scientists Bake Up a Storm in Service of Better Cookies

Every time we bake, we transform our kitchens into chemistry labs. And sometimes the opposite is true: labs become kitchens where researchers run scientific experiments to find out what makes the best cookies! That's right, cookie scientists exist - and they're behind new innovations in this classic treat.

Chocolate chip cookies

There are many reasons to study cookies, aside from finding out exactly what happens between the different ingredients in recipes, under different conditions, and using that knowledge to make the ultimate cookie.

These days, many people are seeking alternatives to common ingredients used in classic cookie recipes - wheat, butter, sugar, and eggs - due to dietary restrictions or personal choice. Again, because cooking is chemistry, changing any one of the ingredients will change the texture, taste, shape, and appearance of our final product. Until recently, it was difficult to commercially produce an acceptable gluten-free cookie. But now, thanks to research on interactions between novel ingredients in cookie recipes, we're able to buy cookies made with non-traditional ingredients, but that are similar in taste and texture to traditional-recipe cookies.

Studying cookies can also contribute to making us healthier! Almost universally enjoyed and rarely passed up, cookies are a great place to hide extra nutrition in our diets. For example, some researchers were able to boost the calcium content of cookies by mixing eggshell flour into the recipe, without affecting the taste and texture. Not only does this help provide a necessary nutrient many of us are lacking, it makes great use of a waste product we otherwise would have to manage. We now can find all kinds of cookies that contain ingredients extracted from food waste – waste which can add extra nutrients, fibre, and protein, and help make cookies more nutritious.

What's next in cookie science? Some food engineers are investigating how to apply 3D printing technology to food, and cookies are a great model to base our new techniques on! Though it may seem relatively simple, printing food in complex 3D shapes is more complicated than doing the same with uniform materials such as plastics. The first thing they needed to figure out is how to make cookie dough into a good "ink." Recipes need to be adjusted to make the dough suitable for the extrusion process of 3D printing (think of how the glue comes out of a hot glue gun). The dough needs to be soft enough to flow through a tiny nozzle, but solid enough that it can be built up in multiple layers and not collapse under its own weight. To this effect, they have experimented with different additives, and different proportions of base ingredients such as flour type, fat source, and sweetener source.

But these recipe adjustments also affect how tasty these cookies are, and how well they hold up after baking. Finding the perfect balance requires a lot of trial and error! Through their delicious experiments, researchers are finding that cooking temperature has an impact on how well 3D printed cookies retain their shapes, and that our future 3D printed cookies will be most stable as triangular, cubic, or cylindrical shapes.

By starting simple and finding out which factors are important to consider when making 3D printed cookies, we can then develop techniques to print food with more complex recipes.

The bottom line of all this research? Ingredients and proportions matter, and so does technique. So whichever way you enjoy your cookies, don't be afraid to turn your kitchen into a lab, and run your own recipe trials to find your ultimate cookie!

By Renée-Claude Goulet

Brrreaking it Down: The Science of Cold

For those of us enduring winters that can plummet to thirty below, it might be surprising to learn that cold technically doesn’t exist.

It may seem contradictory, but these people aren’t feeling cold…they’re feeling the movement of heat.

Heat on the other hand is real and measurable. Atoms and molecules have thermal energy which makes them move and shake. Whether it’s an atom in the air, in a snowball, or in a person, the more energy it has, the faster it moves. An object with a high temperature has faster-moving atoms with more energy, while an object with a low temperature has less energetic, slower-moving atoms. When two atoms collide, they transfer energy, and this transfer of thermal energy is called heat.

Let’s imagine an inflated balloon. When you heat it up, it gets bigger; when you cool it down, it gets smaller. These size changes happen without changing the amount of air inside the balloon! Why? Because the air inside an inflated balloon has energy that causes the air molecules to move, bouncing against each other and bouncing against the walls of the balloon, pushing them outward. Heating the balloon adds energy to the air inside, causing the molecules to move faster and to hit the walls with more force, expanding the balloon even more. Conversely, when the balloon loses energy (as it cools down), it shrinks because the air molecules inside move more slowly and hit the walls with less force.

Temperature measures how much energy the particles of an object or substance have. Things can have or not have energy, but they can't have something called “cold”. Similarly, silence isn’t a thing (it’s just the absence of sound waves), and darkness isn’t a thing (it’s just the absence of light). In other words, you can add heat to something, just as you can add light or sound. But you cannot add cold, darkness, or silence.

So if cold isn’t a real thing, what are we feeling when we leave a building without a coat at -10°C? It's not that there are pieces of "cold" in the air. What we’re feeling is the flow of energy away from our bodies. This makes our body’s atoms vibrate a little bit less, and the atoms in the nearby air vibrate and move a little bit more. We feel ‘cool’ when we transfer a little bit of heat, and we feel ‘cold’ when we transfer a lot.

Go Further:

Even if cold doesn’t technically exist, you still want to conserve your body’s thermal energy when it is less hot outside. Find out why wool is so effective at keeping us warm and why moving air (i.e., wind) can make us feel even colder.

By Michelle Campbell Mekarski

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!