An ideal topic for a month of April: 20 000 inches under the sea

Bon jorn / good day. I have a question for you, my reading friend. Would you like to take a closer look at the wonders that lie beneath the surface of the ocean, without having to transform yourself into a human frog with scuba gear, air tanks, regulator, mask, fins, etc.? Yes, I know, there are aquariums that offer such an experience. Yes, yes, again, I know, some sites offer underwater tours in abundantly glazed submarines. What I’m talking about is very different. What I’m talking about unfortunately only exists in the form of rusted remains gnawed by the waves. If I may quote, out of context, some lines of the song Une belle histoire, a great 1972 success of French singer Michel Fugain, it is a beautiful novel, it is a beautiful story. It is a romance of today – if today was / is the mid-1960s of course.

At that time, the aforementioned aquarium and tourist submarine developments did not exist. Access to the underwater depths in scuba gear was reserved for a tiny minority of sportswomen and sportsmen – or military personnel. Let’s not forget, the first episode of The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau was aired, in English of course, only in September 1966. Both this famous American television series and its creator, the equally famous French author / environmentalist / filmmaker / inventor / oceanographer Jacques-Yves Cousteau, were mentioned in a January 2019 issue of blog / bulletin / thingee.

The main characters in the story that concerns us this week, 2 Frenchmen who loved the mountains, got the idea, around 1961, it seems, to design a device allowing Mrs. and Mr. Anyone, as well as to their offspring, to go underwater and stay there for a few minutes in one of the cabins of the world’s first underwater cable car. This vehicle was far less expensive than a submarine and offered a less distant contact with the seabed. James Couttet and Denis Creissels christened their idea, a thoroughly revolutionary one you will admit, the téléscaphe (TÉLÉphérique + SCAPHandreE, or cable car + diving suit in English).

A mountaineer, elite skier and scuba diving enthusiast, Couttet was the former coach of the French alpine ski team that took part in the VII Olympic Winter Games, which took place in Italy, in 1956. In March 1938, he had become world downhill champion. Couttet was not even 17 years old. Creissels, on the other hand, was an engineer and founder, in 1961, of the consulting firm Denis Creissels Société anonyme, a firm subsequently known as DCSA.

Intrigued by the economic / tourist potential of this suit jacket submarine adventure worthy of Jules Gabriel Verne, the École nationale des ponts et chaussées and the city of Marseille offered their support. Work began in 1966 in Callelongue, a small fishing village located near this great Mediterranean city. This work proved very expensive, for reasons of safety. And yes, my reading friend fascinated by youth literature, Verne was mentioned in some issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, and that since June 2018.

Why Callelongue, you ask, my reading friend? Better yet, what was / is a téléscaphe? Two good questions. Regarding the first, the fact was that that neck of the woods was full of fish, a key factor for any underwater stroll. The seabed was also exceptionally beautiful.

An answer to your second question will take a bit more time. Are you ready? Let’s go. The waterproof cabins, painted bright yellow, undoubtedly formed the heart of the téléscaphe. Up to 6 people could take place on the base of each of them. Once all these good people were onboard, sitting on the 2 upholstered benches perhaps, the staff lowered the main part of the cabin which slid on a central vertical axis. Six large reinforced windows and 2 portholes in the roof gave passengers exceptional visibility. It should be noted that a 2-seat version of the operational cabin was seemingly to be used for tests in 1966. Both versions were manufactured by a Swiss company specializing in cable cars. A collaborator of Cousteau participated in the design of the cabins.

Would you believe that a newlywed couple participated in one of the tests in 1966? You don’t believe me? That’s shameful. So go take a look at

If truth be told, yours truly cannot confirm that the young couple in question was recently married. They might have been actors, for example, but back to our story.

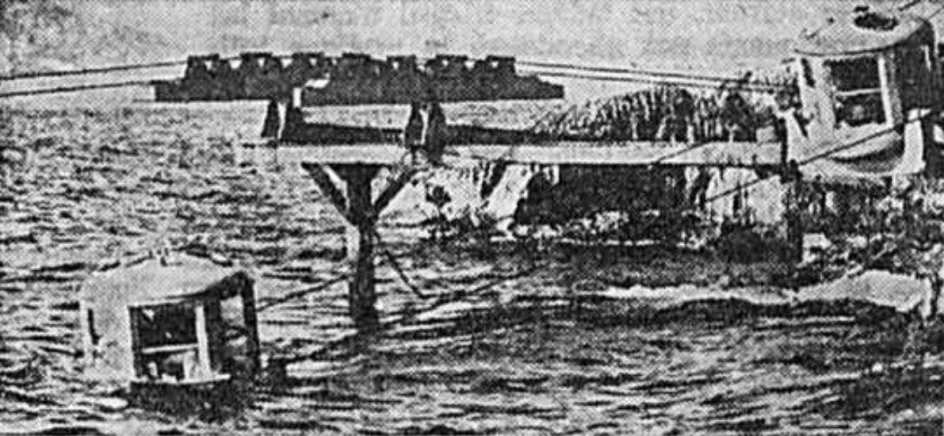

Once all cabins were filled, they began their journey by sliding on a rail. Once under water, 2 horizontal cables operated by 2 groups of winches placed in 2 stations in the open air took over and ensured the movements of the cabins over a distance of about 250 meters (820 feet), traveled in 10 minutes, about 10 meters (33 feet) below the surface at its deepest point. The cabins then stopped for a brief moment before repeating the same course, in the opposite direction and at the same speed. If the téléscaphe apparently did not offer any service in bad weather, it could work both day and night. Once back on land, each passenger received a first dive card in memory of these unforgettable 50 000 centimetres (20 000 inches) under the sea.

Emergency equipment allowed passengers to wait for assistance for almost 6 hours in case of mechanical failure. In a serious emergency, the divers(s) who were / was permanently on guard could detach any cabin. Passengers could also do the same with an easily accessible lever. In one case as in the other, the cabin immediately rose to the surface. Two inflatable balloons apparently increased its buoyancy. Passengers could leave the cabin through the portholes in the ceiling. A cable connected the cabin to one of the horizontal cables, thus avoiding drifting.

Aware of the importance of offering a beautiful show, Couttet and Creissels oversaw the immersion of an old boat and of other decorative elements. They guaranteed the presence of many fish by placing nets along the road followed by the cabins.

The official launch of the téléscaphe took place late June 1967, in the middle of the night, to maximize the impact. Said launch may have counted among the elements of the first program conceived in mondovision, Our World, broadcasted at the end of June 1967, and ... You have not the least idea of what mondovision was / is, have you? If I may quote the source of all knowledge that is Wikipedia, in translation, “mondovision was / is the simultaneous broadcast of a television program in the maximum number of countries of the world.” From 400 to 700 million viewers thus saw what happened in Callelongue, and ... No, my reading friend, the téléscaphe was not the main element of Our World. That was actually a performance by a British pop band you may have heard about, the Beatles. They one plays a 1967 song you may know, All You Need Is Love.

This being said (typed), the general public only had access to the téléscaphe on 1 July 1967, a day that, coincidentally, was also Canada’s 100th birthday, and ... You’re still skeptical, aren’t you? May I suggest that you watch

As one would expect, the téléscaphe did not go unnoticed in France and elsewhere. The October 1967 issue of Le jeune scientifique contained an illustrated article of French origin entitled “Opération ‘20,000 yeux sous les mers’,” for example. This Québec monthly published by the Association canadienne-française pour l’avancement des sciences, an organization mentioned in a December 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, was the ancestor of Québec Science, a respected magazine published since 1969.

The 4 operational cabins of the 1967 season allowed about 10 000 people to visit the seabed safely. The queues under the blazing sun were not particularly popular, however. As fascinated as the passengers and passengers of the téléscaphe were by the spectacle that was offered to them, their presence under the waves did not go unnoticed. The aforementioned Cousteau quipped to that effect: “It is said that cows feel a certain pleasure watching trains go by. We discover today that fish are very interested in the comings and goings of téléscaphe cabins.”

Couttet and Creissels expected to have 20 cabins even before the end of the 1968 season. No less than 5 000 people a day could make a short trip under the waves. Said trip would also be improved following the introduction of an underwater sound and light show. Couttet and Creissels apparently planned to erect a cable car to access a nearby island on which they wanted to build a panoramic restaurant. They also planned to use other téléscaphes to transport passengers between point A and point B, creating a real underwater cable car. The sky, or was it the sea, was the limit.

The 1968 season apparently began very well. There were no fewer than 21 000 passengers. Despite this success, Couttet and Creissels were unable to find private and / or government investors. The political crisis that shook France from May 1968 onward probably explained in part this state of affairs. Worse still, at least one incident that caused no injury undermined public and financial confidence: a couple and their 2 children may have evacuates a cabin that had overturned.

The téléscaphe made its last trip in 1968. It may well have been retired before the end of the season, which normally lasted from May to October.

You seem puzzled, my Sherlockian reading friend. You too noted the fact that the article in Photo-Journal, which was the home port of this article, was published in April 1969, several months after the téléscaphe was shelved, haven’t you? I must confess I too am quite puzzled. At that time, Couttet and Creissels may still have hoped to revive their invention. In fact, the article in the Montréal weekly mentioned that groups in Spain and Japan want to build téléscaphes. Assuming that this statement was correct, these projects went nowhere. Over the years, some groups considered the possibility of resuscitating the téléscaphe. Again, these projects went nowhere.

Couttet died in November 1997, at the age of 76. Creissels, meanwhile, had a great career in the field of cable cars. He left DCSA in 1995 and later founded Creissels Technologies Société à responsabilité limitée. DCSA and Creissels Technologies were still in business in 2019.

What can one conclude from the sad story of the first underwater cable car in the world, except that innovation in science or technology was not / is not / will not be a guarantee of success? In fact, it can pay not to be the one who launches an idea. Many errors can thus be avoided. Take a few seconds to cogitate on this question, my reading friend. A la s’main-ne que vin / see you next week.

More Stories by

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)