An Airway for the freeway: Theodore Parsons Hall and his microcar – and his flying car too

Good morning, my slightly masochistic reading friend. It is with pleasure that I welcome you to the world of aviation and space and, perhaps even more so, of the automobile.

Our topic of the week appeared at the turn of a page of Photo-Journal. More exactly, a page from the 29 December 1949 edition of this Montréal, Québec, weekly, which we all know and love.

The caption of the photograph containing only a minimum of information, yours truly had to invent the rest. Sorry. I’m joking. I did / do not invent a thing, except the more or less successful puns that dot our blog / bulletin / thingee. Here is the legend of said photograph, in translation:

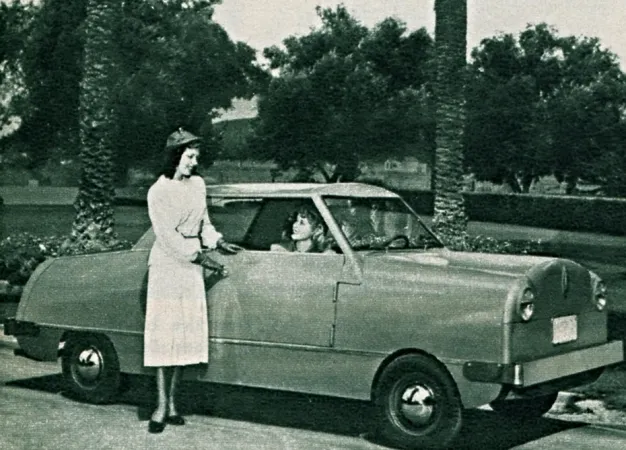

This new light automobile, built to be sold for $500, was launched on the San Diego, California, market by he who designed it, Mr. T. P. Hall. He argues that this car, which weighs [350 kilogrammes] 775 pounds, can reach speeds of [72 kilometres per hour] 45 miles per hour and consumes a single [American] gallon of gasoline for that distance. It is made of an aluminum alloy and a plastic material.

Canada being a metric country, I must add that the Airway consumed 5.2 litres of gasoline per 100 kilometres. Some people knowing the Imperial gallon better than the litre or the American gallon, allow me to say that this microcar could travel 54 miles (87 kilometres) with 1 Imperial gallon (4.55 litres) of gasoline.

Unless you have any objections, yours truly would like to continue this story through a brief biography of the aforementioned T.P. Hall. No objection? Wunderbar.

Said T.P. Hall was actually Theodore Parsons “Ted” Hall, an American aeronautical engineer born in December 1898. Like Howard Joel Wolowitz, one of the main characters of the American television series The Big Bang Theory, he held a Master’s Degree in Engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a prestigious institution of high learning mentioned in a July 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

It should be noted that Hall’s older brother was also an aeronautical engineer. In fact, Randolph Fordham Hall was perhaps better known than him. This inventor and aircraft designer worked for more than 15 years for one of the major aircraft manufacturers in the United States, Bell Aircraft Corporation, a firm mentioned in August 2018 and February 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

“Ted” Hall, on the other hand, joined the staff of the major American aircraft manufacturer Consolidated Aircraft Corporation in 1931, after a stay at a firm co-founded by his brother. He quickly climbed the ladder and eventually became chief development engineer. Hall contributed to the development of 2 aircraft which played an important role during the Second World War, the Consolidated PBY Catalina maritime reconnaissance flying boat / amphibian and the Consolidated B-24 Liberator heavy bomber / maritime reconnaissance landplane, 2 types of aircraft preserved in the very, very impressive collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa, Ontario.

Did you know, my wing nutty reading friend, that the Catalina was manufactured under license in Canada during the Second World War? Would you like to know more about this? No? No?! What do you mean, no? Know that the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), an air force mentioned in some issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since November 2017, went looking for a new maritime reconnaissance flying boat in the fall of 1939. It chose a reliable and proven aircraft, the aforementioned Catalina, in December.

Despite this decision, discussions to produce this aircraft in Canada began only after the attack launched by National Socialist Germany in May 1940 which led to the fall of France, in June. They culminated in September with an agreement which provided for the production of the amphibian version of the Catalina, renamed Canso by the RCAF, by 2 Canadian aircraft manufacturers, Boeing Aircraft of Canada Limited of Vancouver, British Columbia, a subsidiary of the American aeronautical giant Boeing Aircraft Company, and Canadian Vickers Limited of Montréal, Québec.

As a first step, Boeing Aircraft of Canada assembled 55 Cansos using parts manufactured by Consolidated Aircraft. This material not being always available in time and in sufficient quantity, the program was delayed. However, a prototype flew in July 1942. In 1943, in collaboration with the American and British governments, the Department of Munitions and Supply, the agency responsible for war production in Canada, profoundly altered the production program of the aircraft manufacturer. Boeing Aircraft of Canada thus produced just over 300 Catalina flying boats funded by the American government through an Act to Promote the Defense of the United States, better known as the Lend-Lease Act. These aircraft were delivered to the United States Navy, the Royal New Zealand Air Force and the British Royal Air Force.

Canadian Vickers, for its part, received a major Canadian contract in 1941. Its factory in downtown Montréal, somewhat old and congested, was not sufficient for the task, however. The Department of Munitions and Supply then bought vast tracts of land in Cartierville, a suburb of Montréal, and erected a factory that the aircraft manufacturer would manage independently. The transfer of operations was made once and for all in July 1943, approximately 7 months after the first flight of a prototype, in December 1942. Canadian Vickers having decided to abandon aeronautical production in the summer of 1944, a Crown corporation, Canadair Limited, was established in October and took control of the plant in November. Canadian Vickers and Canadair ultimately produced about 370 amphibian aircraft for the RCAF and United States Army Air Forces (USAAF).

The total production of Boeing Aircraft of Canada and Canadian Vickers / Canadair was therefore approximately 730 amphibians and flying boats. The PBY Catalina / Canso was / is one of the most successful maritime reconnaissance aircraft of the 20th century.

If I may be permitted a digression, Canadian Vickers and Canadair were mentioned in several / many issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since September 2018 and October 2017 respectively. Boeing Aircraft of Canada, on the other hand, was mentioned in February and March 2019 issues of this publication illustrious among all. Its American parent company, Boeing Aircraft, was honoured, yes, yes, honoured, in the same way in June 2018, July 2018 and March 2019 issues of our you know what, but back to our story.

Hall became interested in a type of vehicle somewhat different from the Catalina around 1938. He actually launched into the development of a flying car / roadable airplane in his spare time. A proof of concept prototype completed during that same spare time may, I repeat may, have flown in 1939 or 1940.

Intrigued by the potential of this flying car, Consolidated Aircraft suggested in 1941 to the United States Army Air Corps / USAAF that this type of vehicle could be useful in transporting special forces teams behind enemy lines. Let’s not forget, the air force of United States Army was then becoming more and more interested in the cargo / transport glider, a new weapon mentioned in February and October 2018 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee and used for the first time in combat in May 1940 by the air force of National Socialist Germany, or Luftwaffe. The aircraft manufacturer could not interest its potential customer, however. In fact, Hall set his flying car project aside when the United States became fully engaged in the Second World War, in December 1941.

Things seemed to remain there until 1944. That year, Consolidated Vultee Aircraft Corporation (Convair), a corporate name adopted in 1943 upon the merger of Consolidated Aircraft with Vultee Aircraft Incorporated, a division of the holding company Aviation Corporation, hired Henry Dreyfuss & Associates, a well-known American industrial design bureau founded by famed American industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss. The aircraft manufacturer was not unaware that the Second World War would not last forever. Its management undertook a strategic effort to develop state-of-the-art civilian aircraft which would replace on the assembly line the aircraft it produced for Allied air forces, once peace was restored.

Many American aircraft manufacturers, well established ones and newly created ones, also hoped to benefit from the return of peace in the world. Undoubtedly, all these good people believed, a great many pilots trained during the conflict would continue to fly once the war was over, aboard modern light / private aircraft.

This being said (typed?), in 1946, Hall sold the rights to his flying car project to a small firm, the Southern Aircraft division of Portable Products Corporation, to complete its development. His decision may have been due to the fact that Convair’s management did not want to hinder the sales of an updated version of an excellent and highly popular 4-seat light / private airplane that could not be more conventional, which dated from before the Second World War, the Model 108 Voyager, produced by the Stinson Division of Convair.

Anyway, a (improved?) prototype of the flying car designed by Hall, the Southern Aerocar, flew in 1946 or 1947. Would you believe that a drawing of this 2-seat flying car was / is on the magnificent poster of the temporary exhibition Retrospective on the Future (Hello, LG!), inaugurated in 2000 by the National Aviation Museum / Canada Aviation Museum, today’s Canada Aviation and Space Museum?

After a few months, however, Southern Aircraft returned the rights of the Aerocar to Hall. The latter then left his job at Convair to continue developing his flying car. This being said (typed?), the aircraft manufacturer agreed to support the efforts of its former engineer – perhaps not too enthusiastically.

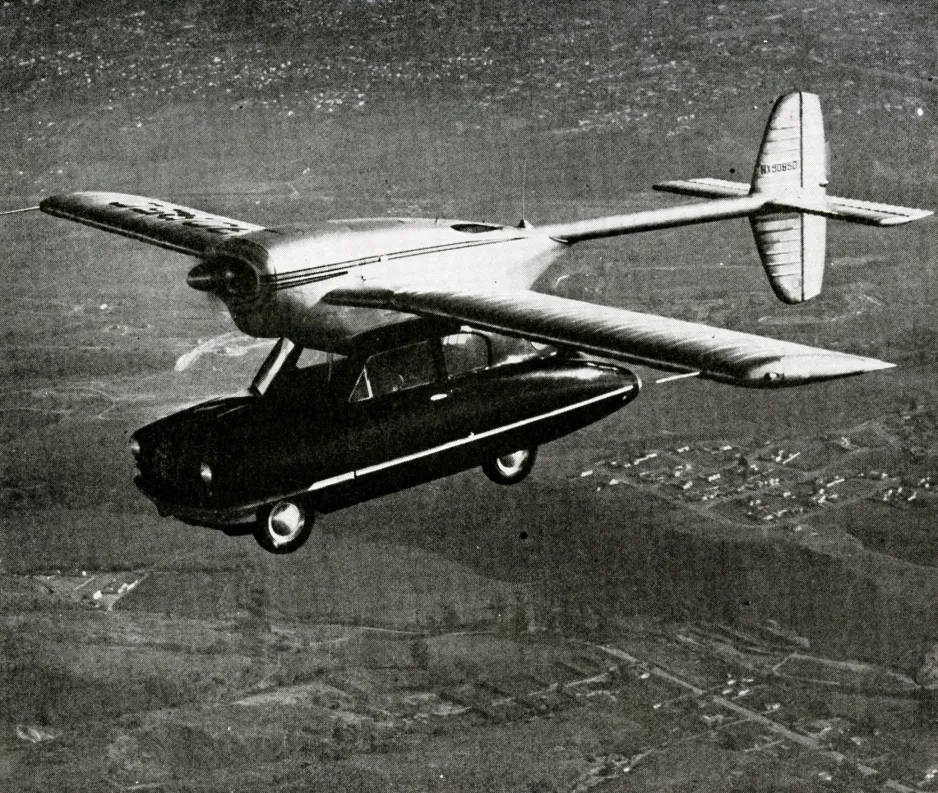

The prototype of the 2-seat Convair Model 116 flying car flew in July 1946. A somewhat amusing detail if I may be permitted: the rear of the automobile part of the vehicle, which was not very elegant according to yours truly, was painted so that it would look like that of a family car. This vehicle made many flights but was certainly not perfect.

The first prototype of the Consolidated Vultee Model 118 flying car. Anon., “Fly it... or drive it.” Skyways, September 1948, 25.

The design of an improved and more powerful flying car, the Model 118, or ConvairCar / Convaircar as it was sometimes / often called, more or less unofficially, thus soon started. To do this, Convair relied again on the excellent services of Henry Dreyfuss & Associates. The latter, on the other hand, relied on the excellent services of a rather peripatetic automobile designer, the talented, resilient, imaginative and competent Wellington Everett “Ev” Miller. The latter prepared plans and a model of the flying car for Henry Dreyfuss & Associates in 1947.

You know what, my reading friend, Miller’s career was / is so interesting that I intend to pontificate about him.

3, 2, 1, go! Born in November 1904, Miller entered the job market in 1919 as a mechanic’s helper. Around 1919-21, following the advice of a subsequent boss, Miller followed the well-known 2-year automobile design and styling course of the Correspondence School for Automobile Body Makers, Designers and Draftsmen founded by Andrew F. Johnson, the father of automobile styling and design in the United States. He designed his first car in 1921.

Miller worked for a myriad of automobile manufacturers, often small ones, starting in the 1910s. He did a lot of that work as a freelance designer. Indeed, Miller remained active until the mid-1970s. During his career, he designed a myriad of products for a hundred or so customers, from water pumps to model aircraft engines as well as cameras, advertisements, vending machines and wheeled toys.

Would you believe that Miller prepared, in 1925, a set of plans of the folding wing flying car that the American Virgil Bertram “Bert / Fudge” Moore wanted to manufacture? The latter, a charming and clever pilot, had actually planned to produce such a vehicle, originally called the Imperial Valley Road Runner, since the very early 1920s. Moore founded at least 2 companies for this purpose, Moore Autoplane Company Incorporated and Pacific Autoplane Company. A prototype, which seemingly flew, no later than 1923, was to give rise to 3 distinct types of vehicles, a taxi, a light truck and a vehicle for travelling salesmen. By the way, Miller did not receive the emoluments he was promised after a month of work.

Moore’s project was of interest to more than one person. In 1921, for example, representatives of the Japanese government who scoured California in search of interesting patents apparently communicated with the young businessman, and with several other people pilots and designers. Yours truly does not know if he sold them anything.

I must also note that Moore was arrested in 1922 for his alleged involvement in a human smuggling ring that brought Chinese people to California from Mexico. This criminal group was also accused of committing bank robberies and smuggling alcohol. Unfortunately, I do not know if Moore was acquitted – or sentenced to prison. He was certainly a free man in 1925.

What is also certain was / is that investors ultimately decided not to launch the production of Moore’s quite innovative vehicles.

If I may be permitted, Moore’s Autoplane should not be confused with

- the Curtiss Autoplane, in all probability the first flying car in the world, and this even if it only made a few hops, completed in 1917 by Curtiss Airplane & Motor Company, an American aeronautical giant mentioned in April 2018 and March 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, or

- the Lebouder Autoplane completed in 1973 by Frenchman Robert Lebouder and tested on more than one occasion.

Neither of these very interesting vehicles went beyond the prototype stage.

Miller also designed luxury automobiles (bodywork and / or interiors) for American film stars such as Douglas Fairbanks, born Douglas Elton Thomas Ullman; William Clark Gable; Thomas Edwin “Tom” Mix, born Thomas Hezikiah Mix; Mary Pickford, born Gladys Louise Smith; and Rudolph “Rudy” Valentino, born Rodolfo Alfonso Raffaello Filibert Pierre Guglielmi di Valentina of Antonguella. He may, I repeat may, have designed an automobile for Mary Jane “Mae” West, a larger than life American actress, screenwriter and singer mentioned in May and October 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Did you know that Gable voluntarily enlisted in the USAAF during the Second World War? He served as a gunner aboard Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bombers.

If I may digress for a moment, Miller was one of the founding members of the Horseless Carriage Club of America, in 1937. He even designed its logo. Miller also served as editor of the magazine of this organisation, The Horseless Carriage Gazette, in the 1960s and early 1970s. He was among the first members of the Classic Car Club of America, founded in 1952. Miller held the position of editor of that organisation’s magazine, The Classic Car, between 1980 and, apparently, 1983.

Over the years, Miller created one of the largest collections of books (3 500), periodicals (7 000), catalogs (25 000) and press clippings (250 000) on the automobile in the United States. His expertise made him an excellent judge of vintage car contests. He was active in this field between the 1960s and the early 1980s. And yes, the W.E. Miller Library of Vehicles still existed as of 2019. It was part of the Nethercutt Collection of Sylmar, California – one of the 5 most important automobile museums in North America. But back to Convair’s flying car, the aforementioned Model 118.

This 4-seat vehicle seemed to have a body made of plastic material. Its driver had 2 separate control systems, a conventional steering wheel and a stick retracting into the cabin ceiling of the vehicle’s automobile part. The motor of said automobile part was at the rear. The wing with its engine could be locked and unlocked easily from said automobile part of the flying car. Three retractable supports, 2 at wingtips and 1 under the tail, supported said wing when the time came to go on an automobile ride. And yes, my reading friend, any user of the Model 118 had to be able to count on a storage space for the wing with its engine.

Over the months, responding to the enthusiasm of the main defender of the project within itself, the management of Convair dreamt of a mass production (up to 160 000 examples?) of its flying car, the most elegant of its time according to yours truly. Available in a great many American airports, the Model 118 could / would be rented by tourists, businessmen or, even more, travelling salesmen.

A prototype of the Model 118 took to the air in November 1947. Three days later, the pilot made an emergency landing when he ran out of gasoline in mid-air. If the latter suffered only minor injuries, like the observer who accompanied him, the automobile part of the vehicle was virtually destroyed. The wing, on the other hand, suffered pretty minor damages. The accident may have been due to the fact that the fuel gauge examined before takeoff indicated the contents of the fuel tank of the vehicle’s automobile part, not that of the tank which supplied the engine of its airplane part.

If a second prototype flew as early as January 1948, the enthusiasm of the management of Convair had flown away. The management of the new parent company of this aircraft manufacturer, Atlas Corporation, shared its opinion. The only real advocate for the project within Convair’s management had to accept the evidence. The flying car was heavier than expected and suffered from tail vibration. Worse still, this expensive vehicle did not cause much public enthusiasm. The crash of the prototype certainly did not improve things, and this even if the basic concept of the vehicle was not to blame.

Indeed, if sales of light / private aircraft reached a record level in 1946, they soon collapsed, taking with them most of the newly founded aircraft manufacturers. Most of the companies which survived the hecatomb produced aircraft that could not be more conventional. Convair’s Stinson Division, let’s not forget, was producing the aforementioned Voyager. This aircraft manufacturer did not want to use any of its resources to try to produce a flying car if that affected the sales of this aircraft.

Convair’s management apparently decided to abandon its flying car well before the end of the summer of 1948. The market for light / private aircraft had dropped to such an extent that it thought of selling its Stinson Division, and including said flying car in the lot. Piper Aircraft Corporation acquired said Stinson Division of Convair in late 1948. The latter’s flying car did not interest at all the management of this well-known American light / private aircraft manufacturer.

Given the circumstances, Convair abandoned its flying car project. The aircraft manufacturer gave back the rights of the Model 118, along with the still working prototype, to Hall, who had founded / founded T.P. Hall Engineering Corporation to bring his dream to a successful conclusion. Convair thus forwent for good the production of light / private aircraft for the civilian market.

If I may be permitted, Hall should not be confused with Charles Ward Hall, the founder of Hall-Aluminum Aircraft Corporation, a tiny American aircraft manufacturer bought by Consolidated Aircraft in 1940 and a pioneer in the use of aluminum in aviation, in the mid-1920s, who had died in August 1936. As well, Hall should not be confused with William D. Hall, the chief engineer of Aeronca Aircraft Corporation, a well-known American light / private aircraft manufacturer, around 1945.

As well, T.P. Hall Engineering should not be confused with Hall Engineering Company of Montréal, a marine engineering and construction company founded around 1902 by Thomas Hall, a director of Montreal Drydock & Ship Repairing Company Limited and Montreal Shipbuilding Company at the beginning of the 20th century.

Would you believe that this Hall, yes, Thomas Hall, was the founding president of Laurentide Air Service Limited of Montréal, one of the pioneers of bush flying in Québec, and hence in Canada, founded in 1922? He was in fact the main investor of this company, which was mainly based at Lac à la Tortue, not far from Shawinigan, Québec.

As you know, the remains of an American Curtiss HS-2L flying boat flown by Laurentide Air Service are on the floor of the dazzling Canada Aviation and Space Museum. A replica / reproduction of this historic aircraft that has no equal in the rest of the world is right next to said remains.

The first pilot of this HS-2L, in June 1919, was none other than Stuart Graham, the first bush pilot in Québec / Canada and a gentleman mentioned in August 2017, December 2017 and January 2018 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, but back to Hall and his plans, because I’m still digressing.

Despite Hall’s efforts, his flying car was not put in production. In fact, none of the flying cars designed in the 20th century was put in production. This situation was equally true at the end of 2019.

Yours truly must admit to having serious doubts about the practicality of the flying car as a means of transport. If you think that rush hour in a metropolis can be stressful, imagine such a rush hour in 3 dimensions, in winter, at sunset, with some snow. Ouhhh, I shiver just to think about it.

This being said (typed), I must point out just how much the Fulton FA-3 Airphibian flying car borrowed in 2000 from the National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in Washington, District of Columbia, by the illustrious, no, no, I’m not exaggerating, the illustrious Canada Aviation and Space Museum, as part of the aforementioned temporary exhibit Retrospective on the Future, was popular with visitors.

The enthusiasm expressed by many young people (“Look, Mommy, a car plane!”) could be found in many people of adult age, even if only chronologically. Just think of a rather memorable television commercial from International Business Machines Corporation, an American computer giant mentioned in January and March 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee. American actor Avery Franklin Brooks, the Benjamin Lafayette “Ben” Sisko of the science fiction television series Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, aired for the first time between January 1993 and June 1999, made a strongly felt comment to that effect: “It is the year 2000, but where are the flying cars? I was promised flying cars. I don’t see any flying cars. Why? Why? Why?”

Given this popularity, say I, yours truly sincerely believes that a temporary (traveling?) exhibition on flying cars, past, present and future, would be most popular with visitors to the Canada Aviation and Space Museum. May I be permitted to suggest the use of 2 excellent books on this question:

- Les voitures volantes: Souvenirs d’un futur rêvé, by Patrick J. Gyger (2005), and

- Les nouvelles voitures volantes: La mobilité porte à porte, by Andreas Reinhard and Patrick J. Gyger (2018)?

Just sayin’.

And yes, I would willingly be the curator of this exhibition. (Hello, SB, EG and EP!)

And yes again, the NASM, one of the Smithsonian Institution’s flagship museums and one of the great air and space museums on our planet, has been mentioned in some issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since November 2017, and ... I think the time has come to pick up the thread of our story. Which is tantamount to saying it’s time to talk (type?) about our topic of the week, the Airway microcar.

Hall founded Airways Motors Incorporated, no later than the summer of 1948, to oversee the production of said Airway. This small company then tried to attract dealers interested in selling the vehicle. And yes, my reading friend, some people suggested that the aforementioned Miller contributed to the development of the Airway. Yours truly must admit to having some doubts, but it is quite possible.

Nicknamed the Vicinity Car, this vehicle not without elegance and apparently applauded by critics was equally apparently to be produced in 2 versions. The coupe and sedan, a tad more spacious, seemed to accommodate 3 people. An optional rear seat (for 2 or 3 people?) would also be available for the second version. The aluminum chassis and body of the prototypes were to give way to a combination of aluminum and plastic material on production Airways. Hall being unable to rely on a factory to manufacture his vehicle, he hoped to sell the production rights of the Airway to at least one (American?) company.

Aimed at wives doing their shopping and / or husbands going to work, long live patriarchy!, the Airway may have been the most luxurious and impressive microcar designed in the United States in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Would you believe me if I told you that the tiny engine (7.35 kilowatts / 10 metric horsepower (10 imperial horsepower)) of the Airway was produced by an American company, D.W. Onan & Sons Incorporated, which, once it became Onan Corporation, produced the small engine that equipped the famous American homebuilt aircraft Quickie Quickie? Did you know that the collection of the breathtaking Canada Aviation and Space Museum included an aircraft of this type? My apologies, I digress.

A brand new Airway costing about as much as a much more comfortable, fast, powerful, robust and spacious used American car, you will not be surprised to read (hear?) that it was not put in production. In April 1953 at the latest, a small ad from T. P. Hall Engineering announced that the entire project, then referred to as the Airway Scooter Car, was for sale. It should be noted that said ad included a photograph of a convertible Airway, which was rather curious. You see, some sources suggested / suggest that only 2 Airways were manufactured around 1949-50, a coupe and a sedan.

If truth be told, none of the American microcars was successful. If I may be permitted to paraphrase the well-known words of the German-born British economist Ernst Friedrich “Fritz” Schumacher to the negative, small was not beautiful in this case.

No example of Hall’s flying cars and microcar survived as of 2019. Pity.

Hall and Miller left this world in March 1978 and April 1983. They were both 79 years old.

Peace and long life to you.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)