A satellite called Trudeau, Satty Chatty, Rendez-vous, or… Anik

Hello, dzień dobry and ublaahatsiatkut. I hope that the stars are favorable to you, my reading friend, and I use this expression knowing full well that astrology is a pseudoscience without any real foundation.

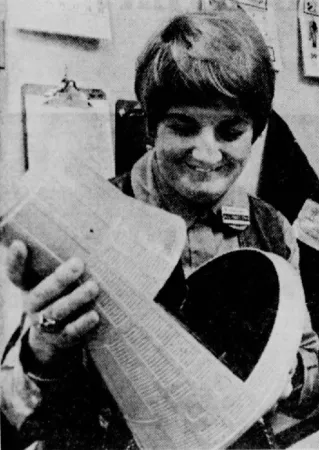

Would you like to know all the data with which I started writing this issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee? Wunderbar. Allow me to quote the legend of the photograph above, in translation, extracted from the 23 November 1969 issue of the weekly, earlier on daily, La Patrie of Montréal, Québec.

Julie-France [Czapla] is the Canadian who found the name of our first communications satellite. She suggested “Anik” and “Anik” which means [little] brother in [Inuktitut] was retained. Julie-France (a charming name) will receive a trip at the expense of the government to Cape Kennedy, where she will attend the launch of the satellite. The 24-year-old is a bookkeeper at the Miracle Mart of the Centre commercial de Dollard-des-Ormeaux. She speaks three languages but does not understand [Inuktitut] at all.

If I may be permitted a few clarifications, Czapla was a resident of what was then the city of Saint-Léonard, in the suburbs of Montréal, who was very good at painting and fascinated by space exploration. Cape Kennedy was called Cape Canaveral as of 2019 while the Centre commercial de Dollard-des-Ormeaux became the Galeries des Sources.

The Miracle Mart Limited chain of discount stores was launched in 1961. It originated from a brief (1961-62) collaboration between Steinberg’s Service Stores Limited, a pioneer in the world of self-service grocery stores in Québec, now gone, mentioned in an August 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, and a chain of department stores in British Columbia, Woodward’s Stores Limited. Let us conclude this brief digression by noting that Miracle Mart went bankrupt in 1992.

Oh, before I forget, the contest rules stated that the winner would attend the launch of the first Canadian domestic communications satellite with a person of her / his choice.

As you may have guessed, it was in November 1969 that the Minister of Communications released the name of said satellite, at a press conference, in Ottawa, Ontario, a few days before Czapla went there to meet him. Eric William Kierans could not help but do a bit of politics at the press conference, stressing how anik / little brother was an appropriate term, given the circumstances.

Indeed, the 2 large communities living in Saint-Léonard, an Italo-Canadian minority wanting to live in English supported by members of the English-speaking elite of Montréal and a French-speaking majority wanting to live in French supported by nationalist circles in Québec, were then confronted with serious school problems of a linguistic nature, dating back to 1967-69, which gave birth to Bill 63, the first linguistic legislation in Québec, then to Bill 22, the ancestors of Bill 101, in force in 2019.

Yours truly remembers hearing a slightly older cousin, for whom I had / have / will always have great affection, mentioning that she wanted to take part in this distant time in one of the numerous demonstrations against Bill 63 or Bill 22, deemed insufficient by many francophone Quebeckers, but back to our history

If I may be permitted a brief anecdote regarding the aforementioned press conference of November 1969, one of the 3 members of the jury who examined the suggested names for the first Canadian domestic communications satellite, author composer interpreter, musician, painter, poet and writer Leonard Norman Cohen, of Montréal, indicated, with a slight smile, that said jury also thought of choosing the Inuktitut word anak or, more precisely, anaq. It quickly changed its mind. You see, anaq means… excrement / shit in Inuktitut.

Czapla being described as the person who had found the name of said satellite, you are probably wondering by what means this name was chosen. I would love to enlighten you.

In a first step, let’s see how Czapla came to choose the word anik. She actually explained this process to the Department of Communications representative who contacted her to tell her that she had won the contest. Anik, said Czapla, was the name given to the daughter of one of her friends in Québec, Québec – a detail that was both accurate and inaccurate. Let me digress, sorry, clarify my thought.

Arsène Jezequel had just spent 1 year (or 2?) in Povungnituk, today’s Puvirnituq, an Inuit community in northern Québec. This employee of French / Breton origin of the Québec Ministère des Richesses naturelles kept an undying memory of his stay. His wife, Rachel Lessard Jezequel, having given birth to a daughter in January 1969, he suggested that they name her Annick, a Breton name similar to the Inuktitut word anik. The couple ultimately decided to name their child Julie Annick Jezequel. This person was apparently still doing very well in 2019.

Yours truly unfortunately does not know if Czapla, who was / is about 74 years old in 2019, was / is still with us.

In a second step, let’s go back to the process leading up to the November 1969 press conference. This beautiful story began in June. The aforementioned Kierans then launched a contest to name the first Canadian domestic communications satellite.

The suggested names would have to work in both French and English. Names in Indigenous languages were also welcome. In either case, the suggested names had to be distinctively Canadian.

The 3 people who would judge the suggestions were well known to the public:

- the aforementioned Leonard Norman Cohen;

- Gratien Gélinas, actor, author, director, playwright, producer and writer from Montréal; and.

- Herbert Marshall McLuhan, theorist / philosopher / guru of mass communications and director of the Center for Culture and Technology at the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

You will note that there was no woman, no representative of a First Nation, etc. within this jury.

Nearly 3 weeks before the end of the contest, scheduled for 1 October, the Department of Communications said it had received more than 20 000 suggestions. This public interest took the staff of this department, which had to examine mountains of letters, totally off guard. In fact, some / many suggestions came from people (of Canadian nationality?) residing in the United States.

While many Canadians offered the inevitable Canada and Adanac, some people mentioned the names of Kierans and Prime Minister Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau, also known under the moniker PET. You will understand that yours truly mentioned this moniker, apparently proposed as the name of the new satellite, with all due respect. Incidentally, the word pet means fart in French.

The same respect was / is due to the person who suggested that Canada’s first domestic communications satellite be christened Wolfe, after James Wolfe, the British major general who had won the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, near Québec, the city, not the province, in September 1759. This person also suggested that the second Canadian domestic communications satellite be christened Montcalm, after Louis Joseph de Montcalm-Grozon, the French lieutenant general who had suffered defeat in the same battle. Yours truly must confess not to like these suggestions. I find them a little capillotracted.

Names such as Rendez-vous and Voyageur were offered by many people.

A participant may have thought she / he was increasing her / his chances of success by sending 40 names of birds in Indigenous languages.

Some participants showed real imagination and / or humour. A resident of the United States, for example, believed (seriously?) that Satty Chatty was a moniker that could not be more appropriate for a satellite. The leader of the official opposition, Robert Lorne “Bob” Stanfield, a gentleman with a subtle sense of humour, suggested the following names for the first 3 Canadian domestic communications satellites:

- Trudeau, for the aforementioned Prime Minister,

- Benson, for Edgar John “Ben” Benson, Minister of Finance, and

- Sharp, for Mitchell William Sharp, Secretary of State for External Affairs.

As large as were the piles of suggestions received by mid-September, the staff of the Department of Communications expected a large number of schoolchildren and students to participate in the contest before it ended. It was right. As of 1 October, more than 25 000 suggestions had arrived in its offices. Quebeckers sent the greatest number of suggestions, followed by Ontarians.

Could this be the end of this issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee? Nay. Yours truly is not done with you yet. The Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, being a museum of science, technology and innovation, how could I not pontificate on Canada’s first domestic communications satellite?

Recognising the importance of improving communications across Canada and, in particular, in northern regions, the Department of Communications launched the idea of a domestic communications satellite around 1968. Better yet, it wanted these satellites to be made in Canada. A well-known aircraft manufacturer, Canadair Limited of Cartierville, Québec, a subsidiary of the major American firm General Dynamics Corporation, mentioned several times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since March and February 2018 respectively, submitted a proposal regarding the structure and energy system of said satellite, in 1968, for example.

The management of Telesat Canada, a Crown corporation created in May 1969 to operate future Canadian communications satellites, did not necessarily support the idea of making the satellites in Canada. It awarded the contract to Hughes Aircraft Company, a subsidiary of the American company Hughes Tool Company, a firm mentioned in October 2017 and April 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, which claimed to be able to deliver the goods at a lower cost. This decision was certainly not unanimously approved. And yes, Hughes Tool was owned by Howard Robard Hughes, Junior, an individual mentioned in several issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since October 2017.

This being said (typed?), Canadian companies, SPAR Aerospace Products Limited of Toronto and Northern Electric Company of Montréal, still got a share (about 20 %?) of the pie. Better yet, Hughes Tool was committed to offering these same companies a similar share of foreign contracts obtained thereafter.

Placed in geostationary orbits, Anik A1 and its sibling satellites, Anik A2 and A3, launched in November 1972, April 1973 and May 1975, could transmit 12 television programs at a time or the equivalent of 11 520 one-way telephone channels. They were withdrawn from service in July 1982, October 1982 and November 1984, well after their scheduled retirement dates.

Why send 3 satellites, you wonder, my reading friend? In order to guarantee a continuous service whatever happened, be it a meteor impact in orbit or a rocket explosion at launch, an operator had to be able to count on a spare satellite.

With these satellites, Canada became the first country in the world to have a domestic communications satellite system.

In 1973, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation / Société Radio-Canada became the first broadcaster in the world to use satellites for the full-time distribution of television programs.

If I may be permitted a brief digression, the structure of the Anik A1, A2 and A3 satellites derived from that of the Intelsat IV communications satellites ordered in October 1968 by the American firm Communications Satellite Corporation on behalf of International Telecommunications Satellite Consortium (Intelsat), an international intergovernmental organisation dominated by the United States. The Intelsat IV satellites ordered at this time were the most imposing ones designed until then. The first and last of the 8 satellites in this series were placed in orbit in January 1971 and May 1975.

Would you believe that a 1/3 scale model of the Anik A1, A2 and A3 satellites is on display on the floor of the fabulous Canada Aviation and Space Museum?

Civil servants, engineers, managers and politicians welcomed the fact that the Anik A1, A2 and A3 satellites allowed Canadian Broadcasting Corporation / Société Radio-Canada broadcast signals to reach Canada’s north for the first time. They also allowed the broadcast signals of the latter to reach the western part of the country while facilitating communications from sea to sea. These satellites actually gave northern communities access to a reliable telecommunications network – a first for this isolated region of the country. To that effect, it should be noted that Inuit communities in northern Québec used Anik A satellites to establish an interactive radio network.

While acknowledging the importance and usefulness of satellite communication, a study on communications in northern Canada published in 1971 by the Arctic Institute of North America of McGill University, a Montréal-based institution of high learning mentioned in several issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since December 2018, pointed out that the planned programming of Anik A1, A2 and A3 satellites did not meet the needs of populations in northern Canada, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous.

First Nations spokespersons pointed out that American television series such as I Love Lucy or Bonanza meant nothing to them. Worse still, the snow-white heroes of the latter killed many members of various First Nations before leaving the airwaves, in January 1973. In this series as in others, the whites always won.

And yes, you are right, my telephile reading friend, Lorne Greene, born Lorne Himan Green, a Canadian actor mentioned in September 2018 and February 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, was one of the stars of Bonanza.

The Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, Joseph Jacques Jean Chrétien, also agreed that the Indigenous people in northern Canada should have access to programming that resembled them. We could not sell them the same sorts of soups that were eaten in Toronto, said he.

Half a century after this comment, a lot remains to be done, but that’s another story.

I will not tell you anything you did not already know, my reading friend, by saying (typing?) that other satellites of the Anik family were placed in orbit after Anik A1, A2 and A3:

- Anik B1, in December 1978;

- Anik C3, C2 and C1, in November 1982, June 1983 and April 1985;

- Anik D1 and D2, in August 1982 and November 1984;

- Anik E2 and E1, in April and September 1991;

- Anik F1, F2, F1R and F3, in November 2000, July 2004, September 2005 and April 2007; and

- Anik G1, in April 2013.

It should be noted that these increasingly powerful and sophisticated satellites, still controlled as of 2019 by Telesat Canada, a subsidiary of Telesat Holdings Incorporated, itself a subsidiary of the American telecommunications company Loral Space & Communications Incorporated and of the Canadian Crown corporation PSP Investments, one of the largest fund managers for pension plans in Canada, were / are designed / manufactured by various companies.

Anik F1, F2, F1R, F3 and G1 were still operational as of November 2019.

Goodbye, do wizdenia and tavvauvutit.

By the way, the term capillotracted refers to a story drawn by the hair, in other words far fetched.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)