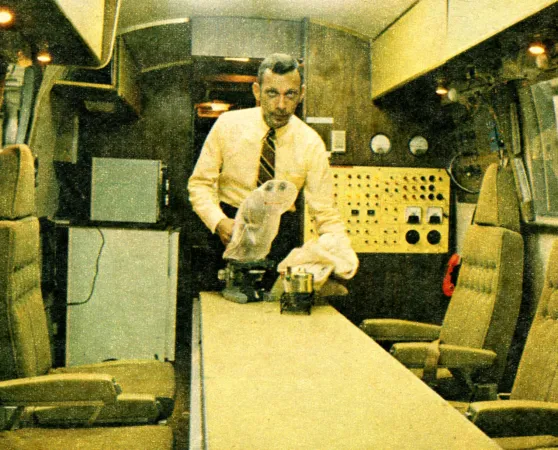

A real McCoy, space doctor William Richard Carpentier

Dammit, my reading friend, I’m a museum curator, not a doctor. Sorry. That was uncalled for – and rather quirky as an opening sentence. Still, I couldn’t resist this little Star Trek joke, and… You do get it, don’t you? Dammit, Jim, I’m a doctor, not a whatever happened to be the flavour of the week? Sigh… What do people learn in school these days? There is no respect for the classics. To quote Marvin, the paranoid android in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, magnificently played by Alan Sidney Patrick Rickman in the 2005 eponymous movie, I’m so depressed. And yes, my reading friend, the hit British Broadcasting Corporation radio comedy show which inspired this feature film was mentioned in a March 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

So, we are gathered here today to pontificate and, in your case, absorb a lot of knowledge, on a seemingly poorly known giant of space medicine. By the way, did you know I was tempted to use the words “Space medicine is what I need” as a title for this article? Hello, EP, EG and SB! Space medicine, bad medicine? Bon Jovi? You did get that one? Good, but back to our story, and what a story it was / is!

It all began in Edmonton, Alberta, in March 1936, with the birth of William Richard “Bill / WFP” Carpentier, and… What’s this I hear? What does WFP mean, you ask, my puzzled reading friend. To quote an unknown philosopher, all things come to those who wait.

Carpentier moved to British Columbia with his family in 1945. This bright and adventurous young man initially wanted to become an engineer. Two years of physics classes at the University of Victoria convinced him otherwise. I, for one, can sympathise. A tour of a hospital offered by his sister, a nurse, opened his eyes. Carpentier thought that his future laid in psychiatry. Two years of classes at university convinced him otherwise. Even so, Carpentier graduated from the University of British Columbia in 1961. By then, he had acquired a private pilot license and an interest in aviation medicine. Even before the end of that same year, Carpentier had moved to the United States with his spouse to begin a 2 year residency in aviation medicine.

Like countless people around the globe, Carpentier was fascinated by news reports on Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin, the first human being to go into space, in April 1961. As we both know, this Soviet fighter pilot was mentioned in several issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since July 2018.

Carpentier’s planned return to Canada to earn a doctorate, at McGill University, in Montréal, Québec, and do research, went out the window as a result of a telephone call. The National Aeronautics and Space Agency / Administration (NASA) was looking for individuals willing to undergo a 3 year residency in space medicine. Would he be interested in applying? Would he be? Are you kidding? Carpentier very much wanted to apply but had to point out that he was in the United States on an exchange visitor visa. He didn’t have the green card needed to work in that country. The gentleman at the other end of the line said, and I quote, “we can fix that.”

Six months later, Carpentier had a green card, a security clearance and a job at NASA. He arrived at the Manned Spacecraft Center, today’s Johnson Space Center, in January 1965. Selected as a flight surgeon trainee, he became a fully-fledged flight surgeon in July. Carpentier thus became one of NASA’s first aeromedical clinical investigators responsible for the health and welfare of astronauts.

Carpentier may have caught the eye of his superiors when he readily accepted to become a recovery physician for the Gemini programme, a job for which he might have to jump out of a helicopter, into a churning sea, to treat an injured astronaut. Believing that he might have to jump out of at a speed of 75 or so kilometres / hour (46 miles / hour) 12 or so metres (40 feet) above the water, this excellent swimmer demanded that the United States Coast Guard helicopter pilot he was flying with go that fast and that high. The pilot was aghast, but agreed to drop him from increasing heights and speeds. The training was painful but Carpentier eventually jumped out of a helicopter flying at almost 75 kilometres / hour (46 miles / hour) 12 or so metres (40 feet) above the water.

When Carpentier met the officer in charge of the team of United States Navy scuba divers he would work with, he pointed out the height and speed of the jumps he had made. The officer looked at him as if he was insane. You see, rescue helicopters usually remained in the hover, 6 or so metres (20 feet) above the water, when divers went in. Few, if any of the military divers had attempted what the Canadian doctor had done. As Carpentier’s rescue training began in earnest, the divers knew he meant business.

What is it, my reading friend? You want to know what a flight surgeon did / does? Err, haven’t I told (wrote?) you about 90 seconds ago? You want to know more? Sweet, or is it shiny? It’s hard for an old guy like me to keep up to date with the lingo of today’s young folks. Well, a flight surgeon was / is a doctor / physician with specialised training and a background in aerospace medicine who was / is assigned to each crew when these individuals, in turn, were assigned to a mission. If I may paraphrase a NASA webpage, a flight surgeon oversaw the health care and medical training of her / his crew, when the latter was preparing for its mission. She / he also took care of any medical issue that arose before, during and after said mission. You know what, there is a small possibility you may have been right to request additional information on what a flight surgeon did / does. Maybe.

Incidentally, the flight surgeon assigned to Canadian astronaut Davis Saint- Jacques was / is Raffi Kuyumjian. Yours truly had the pleasure to meet both of these fine gentlemen, not to mention other fine individuals, when working on a semi-permanent exhibition, Health in Space: Daring to Explore, on display at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario. Hello EP, EG and SB! A travelling version of this exhibition may show up at a venue near you during the next few years. At the risk of sounding like someone who is tooting his own horn, go see it. It is quite cool, but back to our story.

Carpentier was involved with several missions of the Gemini programme. Indeed, he was the doctor on hand aboard the helicopters that picked up the Gemini 5, 6 and 7 astronauts after splashdown. Carpentier then switched to the Apollo programme. He was instrumental in maintaining the gathering of astronaut medical data both before and after each mission. You see, some people wanted to reduce the amount of testing. Carpentier stood his ground, however. The commander of the Apollo 7 mission, Walter Marty “Wally” Schirra, a gentleman mentioned in a July 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, came to believe he was right. This October 1968 mission pretty much set the medical test standards for the rest of the Apollo programme.

This being said (typed?), the Apollo 11 mission of July 1969, which was responsible for the first human landing on an extraterrestrial body, was undoubtedly Carpentier’s favourite. And yes, a Canadian was the flight surgeon of the Apollo 11 crew (Edwin Eugene “Buzz” Aldrin, Junior, Neil Alden Armstrong and Michael Collins). He was there to wish them luck when they boarded their spacecraft. Carpentier was also in the Sikorsky SH-3 Sea King helicopter of the United States Navy that hoisted the 3 astronauts in mid ocean. He checked the vital signs of each man as he got on board. And yes, Apollo 11 was mentioned in a May 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

And yes again, my forgetful reading friend, the positively breathtaking collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum of Ottawa, Ontario, includes a CH-124 Sea King delivered in 2019. And yes again, this type of helicopter was mentioned in a February 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Carpentier and the astronauts left the Sea King together, the latter in their biological isolation garments, and entered the Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF) where they remained 2 weeks, to make sure that no lunar pathogen had been brought back to Earth. The fear of contagion was especially high given that President Richard Milhouse “Tricky Dick” Nixon would be on board the United States Navy aircraft carrier where the astronauts would be during the trip back to the United States. And yes, Nixon was mentioned in a May 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

If truth be told, Carpentier had already spent a week in the MQF with John Hirasaki, a NASA mechanical engineer responsible for maintaining the trailer’s equipment and preparing the lunar samples for shipment. On a less official note, Carpentier and Hirasaki also served as bartender and cook during the trip back to the United States.

The MQF was a converted, airtight trailer made by Airstream Company, an iconic manufacturer if there ever was one. Introduced in 1936, the Airstream Clipper was the first of a long series of trailers with rounded corners on the top and a polished aluminum covering. It was based on designs created by a respected airplane / glider designer, William Hawley Bowlus – a gentleman who had overseen the construction of a highly significant airplane, the Ryan NYP Spirit of St. Louis flown across the Atlantic in May 1927 by Charles Augustus Lindbergh, a gentleman mentioned in September 2017, September 2018 and November 2018 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

In 2019, Airstream was a division of Thor Industries Incorporated, a company that should not be confused with Thor Industries Limited, a firm mentioned in a November 2018 issue of that same blog / bulletin / thingee. You do remember the Thor Automagic combined dishwasher and washing machine, don’t you? Sigh… Let us move on.

Did you know that NASA operated a small fleet of Airstream motor homes to transport astronauts to their launch pads? One of these vehicles was known as, you guessed it, the Astrovan.

When back on shore, the aforementioned MQF was flown to a large quarantine facility with a lounge, kitchen, dormitory, dining room, and many laboratories, known as the Lunar Receiving Laboratory. The astronauts, Carpentier and Hirasaki joined a group of support people who had been sealed in a week before. All of these people spent 2 weeks in quarantine.

If Aldrin, Armstrong and Collins were now the most famous humans on this Earth, Carpentier was undoubtedly the most famous doctor in the United States, and beyond. Sadly, Hirasaki was / is pretty much forgotten.

Between late September and early November 1969, Aldrin, Armstrong, Collins and their spouses, not to mention Carpentier, but not his spouse, took part in a whirlwind tour of the globe known as the Giantstep-Apollo 11 Presidential Goodwill Tour. They visited no less than 22 countries in 38 days – but not Canada.

Would you believe that Aldrin, Armstrong and Collins were in Ottawa in early December 1969? Canada’s Prime Minister, Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau, was on hand to welcome them on Parliament Hill. And if you don’t believe me, you can go to, no, not where you think, my naughty reading friend. You can go to

The 3 astronauts, accompanied by Carpentier, took part in a press conference in Montréal later that week.

Carpentier and his medical team were on hand at all times during the return trip of Apollo 13, in April 1970. His role in that near disaster was such that Nixon awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, one of the highest civilian awards of the United States.

The Canadian doctor was also the flight surgeon of the Apollo 14 crew (Edgar Dean “Ed” Mitchell, Stuart Allen “Stu” Roosa and Alan Bartlett Shepard, Junior), in February 1971.

Given his close contacts with astronauts who had walked on the Moon, Carpentier was sometimes called the moonwalkers’ doctor. How about the acronym WFP, you ask, my patient reading friend? Well, Carpentier earned that moniker, which stands for “World Famous Physician,” when someone seemingly described him as such on a passenger list of Air Force One, a Boeing VC-137 Stratoliner, in other words a specially equipped Model 707 jetliner used by the President of the United States, Nixon in this case.

Carpentier left NASA in 1973. After completing a fellowship in nuclear medicine at Baylor University, in Texas, he became a researcher at Scott & White Memorial Hospital, today’s Baylor Scott & White Health, in Texas. Carpentier seemingly continued to work for NASA, as a part time consultant. He retired in 2003. Remarkably, Carpentier seemingly returned to NASA as a consultant involved in subjects as diverse as astronaut cardiovascular systems and radiation exposure during a future mission to Mars.

For some reason or other, Carpentier renounced his Canadian citizenship in 1993.

A quick question if I may. True or False, was Carpentier Canada’s first space doctor? The answer to that question is… False. A well regarded Royal Canadian Air Force flight surgeon by the name of Dwight Owen Coons joined NASA in 1963 as deputy medical director of the aforementioned Manned Spacecraft Center, which was pretty darn impressive if I do say so myself. He worked on the Gemini programme and helped to design the spacesuit used for the first American spacewalk, made in June 1965 by Edward Higgins “Ed” White II. Coons later helped to prepare the aforementioned Lunar Receiving Laboratory. He was also involved in the selection of the first scientist astronauts, in 1967. Rather popular at NASA, even with most astronauts, who could / can be a tad prickly at times, Coons went into private practice in 1969. This pioneer died in 1997 at the age of 72.

Incidentally, the very first spacewalk took place in March 1965. It was carried out by Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Arkhipovich Leonov, a gentleman mentioned in a December 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Is that all for today, you ask? Well, to quote Gru in the 2010 hit movie Despicable Me, in a totally different context, yes, it is.

I wish to thank all the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, not theirs.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)