Why didn’t somebody tell me that he had one of those… things? Part 1

How do you do, my reading friend? Well? That is wonderful. Let us channel the spirit of our inner Joker, à la John Joseph “Jack” Nicholson of course, and peer into the history of air cushion vehicles, or hovercraft, and… Fear not, brave heart, we shall dwell upon a teeny weeny episode of that history, unfortunately.

The episode that concerns us this week had / has to do with a British gentleman by the name of Peter Mayer. Yours truly wishes I could you provide with some information on the early years of his professional career, but I can’t. I only know Mayer was born in 1934. He became interested in hovercraft when he heard about one of the first full size / successful vehicle of this type, the Saunders Roe SR.N1.

Does the word Roe tell you anything? Yes, that’s right. Edwin Alliott Verdon Roe, founder of A.V. Roe & Company Limited, one of the great aircraft manufacturers of the 20th century, was / is the first British subject to perform, in July 1909, a controlled and sustained flight in a British-made powered airplane in the British Empire. He was mentioned in October 2018, June 2019 and July 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee. And no, the name Saunders unfortunately had nothing to do with David A. “Dave” Saunders, a British-Canadian aeronautical engineer mentioned in August 2017 and July 2019 issues of this same blog / bulletin / thingee.

Did you know that the National Research Development Corporation (NRDC) financially supported the construction of the SR.N1 by Saunders-Roe Limited? This independent public body had formed a subsidiary, Hovercraft Development Limited (HDL), in 1959, to handle all licensing agreements employing ideas developed by the father of the hovercraft, a British engineer named Christopher Sydney Cockerell. And yes, my reading friend, NRDC, HDL and Cockerell were all mentioned in a January 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Incidentally, the SR.N1 “flew” for the first time, over land, in June 1959. The journalists on the scene were so excited by what they saw that they all but begged the management of Saunders-Roe to test the vehicle over water, which was not on the schedule that day. Said management graciously (?) agreed. The impromptu test flight went swimmingly. All in all, the press coverage of the first flights of the SR.N1 was nothing short of considerable, and very positive.

Sadly enough, Saunders-Roe pretty much ceased to exist as an independent entity at some point in 1959. Much of it became the Saunders-Roe Division of Westland Aircraft Limited, a company mentioned in August 2017, May 2018 and February 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Would you believe that the SR.N1 crossed the Channel, from France to England, in July 1959, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the first crossing of this body of water made by an airplane? And who was the pilot of said airplane, ask I? Louis Charles Joseph Blériot, you answer? Bravo, say I. And yes, this gentleman was mentioned in October and November 2018 issuers of our blog / bulletin / thingee, but back to our story.

Mayer’s first hovering experiment entailed the use of a small electrically-powered fan fitted on top of a lampshade (Abat-jour in French. Hello, EP!) bought at a store operated by Woolworth & Company Limited, a division of American retail giant F.W. Woolworth Company. Incidentally, one of the many stores in that defunct chain could be found in Sherbrooke, Québec, where yours truly was born, a long time ago. Mayer’s second experiment entailed the use of a balsa wood model powered by a minuscule (diesel?) engine.

Increasingly intrigued and interested, Mayer decided to build a full scale hovercraft at some point in 1960. He used various bits and pieces to build his creation, including a length of canvas belting used to drive a threshing machine, a tensioning bolt from an adjustable bed spring and a disc coulter from a plough. Even though the propulsion engine of the hovercraft proved so unreliable that it could not be used, the engine that powered the lifting fan worked just fine. With only Mayer on board, the boxy vehicle hovered about 5 centimetres (2 inches) above the ground. With 1 pilot and 1 passenger, it barely cleared said ground. Mayer put this prototype aside in 1961.

By late 1964, Mayer was working on a couple of models that could form the basis of a full scale 4-seat hovercraft. By the summer of 1968 at the latest, he was the rally organiser of the Hover Club of Great Britain, a group known in 2019 as the Hovercraft Club of Great Britain. Mayer did this during his time away from work, of course. Mind you, he was also building a hovercraft. Incidentally, Mayer was a founding member of the Hover Club of Great Britain.

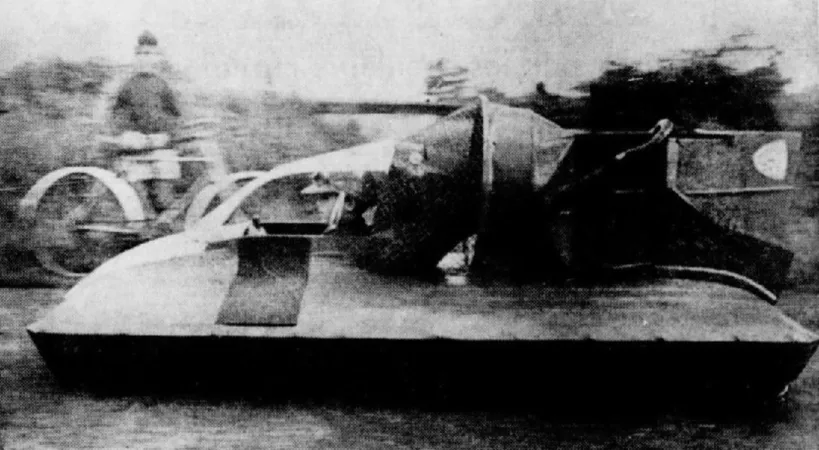

Eager to please his 7-year old son, Guy Mayer, and offer him a present that would be quite unique, Mayer abided by his wish that he built him a single seat scaled down version of the small machine he was working on. According to another source, the young Mayer convinced his father to enlarge the model the latter was designing so that he could ride in it. In any event, Guy Mayer’s hovercraft was completed in early August 1968 at the earliest. Both father and son were very pleased with the performance of the tiny vehicle. Better yet, Mayer senior may have entertained the possibility of building and hopefully selling a few examples of this hovercraft. And yes, my observant reading friend, said vehicle was / is the hovercraft we all saw at the beginning of this article.

By May 1969, Mayer senior had left his position, but not his membership, at the Hover Club of Great Britain. He was about to open a hovercraft school where he would teach, using a 2 seat machine on order, and offer rides to some of the people who were visiting the nearby residence of an earl. Yours truly cannot say how long the school survived.

By March 1973, Mayer was working on a racing hovercraft. Now a member of the council of the Hover Club of Great Britain, he was approached more or less (in)directly by the Department of Trade and Industry. You see, said department wanted to bring a model hovercraft to Zürich, Switzerland, where a British industry exhibition was scheduled to take place. It could not find one, however, and asked Mayer if he could help. The latter readily agreed to give it a go. He build a scaled down version of the racing machine he was working on. Yours truly cannot say of this model went on display, or if the exhibition actually took place.

It should be noted that Mayer was a good friend and working partner of a mechanical engineer by the name of Geoffrey C. “Geoff” Harding during the late 1960s and / or early 1970s. One only needs to think of their work on Wotsit For, the 4th hovercraft of a family of at least 6, tested in December 1971.

Harding, who was heavily involved in public transit, as general manager of the Wallasey Passenger Transport Department, and later as director of the South East Lancashire and North East Cheshire Passenger Transport Executive (SELNEC), was also a hovercraft enthusiast. If truth be told, this founding member, not to mention chairman and president, for a great many years, of the Hover Club of Great Britain, made 35 or so of these vehicles between the very early 1960s and the early 1970s.

In later years, Harding worked the Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive, an organisation which had taken over SELNEC, where he played a crucial role in the introduction of hybrid diesel / electric buses. He may also have been heavily involved in the development of a dual fuel automobile in the 1970s or 1980s.

Ten or so years older than Mayer, Harding had served in the Royal Navy during the Second World War. If truth be told, he was the youngest people involved in one of the most unusual and daring naval actions conducted by the United Kingdom during the conflict. Before reading onward, my reading friend, please note that this action had tragic consequences for several of the people involved.

Rather impressed by the special operations conducted by Fascist Italy’s Regia Marina, its main opponent in the Mediterranean Sea, the Royal Navy set out to develop special weapons of its own. The prototype of a small series of midget submarines, for example, was launched in secret, at night, in March 1942. The X Class submarines, as these small craft were called, were first used in combat in September / October 1943 when 6 of them were towed to a Norwegian fjord where the German battleship Tirpitz was hiding. Three of the submarines, X8, X9 and X10, did not reach their destination, for various reasons; the 3 man ferry crew of one of them, X9, perished. The crews of two other midget submarines, X6 and X7, however, successfully laid 4 explosives charges underneath the Tirpitz that put it out of action until May 1944. Two of the 4 crewmembers of X7 perished. A third midget submarine, X5, was destroyed by the Germans. Its crew may have had had the time to lay its 2 explosive charges. All 4 men perished.

Harding served aboard X10, a ship unofficially named Excalibur. This submarine had to be scuttled while under tow in the North Sea, in early October 1943. All 3 members of its ferry crew survived, but back to hovercraft.

Harding completed in 1967 what was / is undoubtedly one of the most unusual hovercraft ever. The propulsion system of Wotsit 1 consisted of 2 rear-mounted 205 or so litre (45 Imperial gallon; 54 or so American gallon) drums fitted with fibreglass fins, which gave it the appearance of a stern wheeled river boat. Harding wanted to develop a highly maneuverable rescue vehicle capable of operating in every type of terrain one could find in a river estuary. Indeed, he graciously made his vehicle available to a fire department near his home if holidaymakers found themselves marooned by the rising tide.

In October 1967, in atrocious weather (torrential rain, 50 kilometres/hour (30 miles/hour) wind with 80 kilometres/hour (50 miles/hour) gusts), Harding piloted a modified Wotsit 1 all the way up, and down, a 215+ metre (700+ feet) high peninsula with plenty of rocks, grass and bogs, in Wales, thus winning some sort of competition sponsored by John Player & Sons Limited, a well-known tobacco company. To increase his chances of success, he had replaced the drums with a pair of deflated automobile wheels whose axles sported spiked discs. The journey up took 2 or so hours, as did the journey down. To this day, no other hovercraft in the world had achieved such a feat.

British hovercraft enthusiasts initially laughed at Harding. This laughter died when the improved Wotsit 2 began to win races. Several competitors seemingly protested, claiming that the new vehicle, with its unorthodox propulsion system (a single finned drum, buried inside the hull, on land, and an outboard engine at the rear, on water), was not a real hovercraft.

Harding then designed a more conventional vehicle, powered by a couple of ducted fans, seemingly with the help of, you guessed it, Mayer. He raced this hovercraft throughout the 1970s.

Deeply interested in using hovercraft technology in various fields of activity, Harding also developed, in the late 1960s or early 1970s, some sort of hover crutches for individuals suffering from cerebral palsy. A child unable to move was able to, thanks to him.

It should be noted that Mayer also worked with Michael A. “Mike” Pinder, an engineer and founder of Pindair Limited, a company formed in May 1972 to design, develop, produce and market inflatable hovercraft of various size, most of them smallish, for recreational, military and commercial use. Mind you, the company also made a variety of components for sale to amateur hovercraft builders.

You may interested to hear (read?), or not, I will leave that choice with you, all of us being good democrats, that Pinder caught the hoverbug as he designed a way to move giant oil tanks using air cushions. Better yet, he was the individual in charge of the first application of this technology, commercialised by the aforementioned HDL, in 1967.

Pinder developed his first hovercraft around that time, in his spare time, over a 3 year period. The Pinkushion, as this 2-seat design was called, proved quite successful on the British hovercraft racing circuit.

In late 1971, the International Himalayan Hovercraft Expedition hired Pinder to prepare a trio of single seat hovercraft for use on turbulent rivers in Nepal and Bhutan. In 1972, said machines were used there at an altitude of 3 000 or so metres (10 000 or so feet). It looks as if these vehicles were among the first, if not the first Skima 1 hovercraft.

This being said (typed?), the first machine marketed by Pindair was the 2-seat Skima 2. By the mid-1970s, examples of this machine could be found in Africa, America, Asia, Europe and Oceania, in small numbers of course.

The Skima 3 was a rather successful racing version of the Skima 2 seen in the United Kingdom and other European countries. This 3-seat machine available form 1973 onward may have been built to order only. A Skima 3 set a world light / small hovercraft speed record in 1976.

Tested no later than 1973, the 4-seat Skima 4 could be found in all sorts of places, doing all sorts of things. Operators included an aluminium company, some water authorities, a few armed forces, a marine biology research group, a pest research and / or control organisation, flood and beach rescue services, etc.

If one was / is to believe the company’s advertising, a Skima 1, 2, 3 or 4 could be delivered at one’s doorstep, in a large box. Once inflated, and fuelled / oiled, the hovercraft was ready to go. The various small size Skimas were easy to maintain and operate, and quite durable.

Tested around the mid-1970s but not put in production until the end of the decade, if ever, the Skima 6 semi-inflatable hovercraft could carry 6 people in a cabin – or 9 in an open configuration. Some prototypes, known as River Rovers, were tested in Nepal, by members of a joint British Army / Royal Air Force medical expedition, in Indonesia, by missionaries, and on several tributaries of the Amazon. And here lies a tale, that you will read next week.

See ya.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)