Special delivery for Mongo, sorry, Afgar!

Hail, my reading friend. Yours truly wishes to use this week’s topic of our blog / bulletin / thingee to atone, with much delay, unfortunately, for my obvious lack of enthusiasm for a temporary exhibition project, not realized actually, at the National Aviation Museum, today’s Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario. For a variety of reasons, I did not believe that the air cargo industry and its history was an interesting topic. I was wrong. Sorry VD.

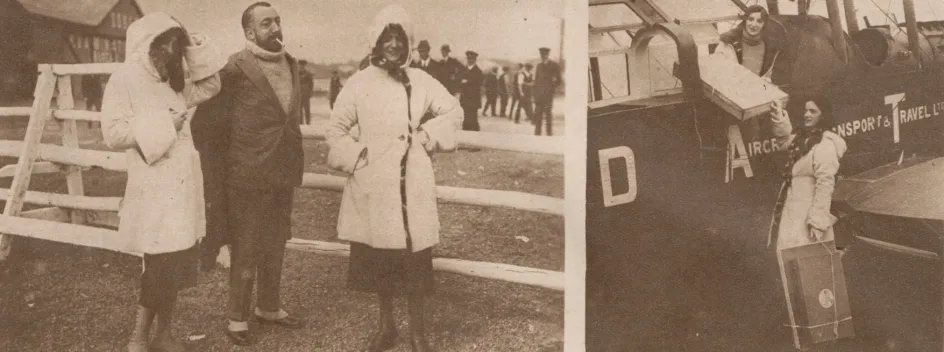

To convince you of this fact, allow me to introduce into evidence the exhibit above, 2 photographs from the 28 September 1919 edition of the weekly Le Miroir, the illustrated supplement of the great French daily Le Petit Parisien – a publication I had not yet used in our blog / bulletin / thingee.

The caption of the 2 photographs read as follows:

THE AEROPLANE EMPLOYED FOR COMMERCIAL TRANSPORT BETWEEN FRANCE AND ENGLAND To deliver theatre costumes to London, a great Parisian fashion designer did not hesitate to use the airplane as a means of transport. He performed the delivery in London, in a few hours, of his impatiently awaited creations.

The term impatiently was most appropriate in the circumstances. The flight(s) in question took place on 16 September 1919, little more than 24 hours before the premiere of the musical Afgar, or the Andalusian Leisure, in London, England. I must admit that I only found the first names of the 2 models who may have flown from Paris to London, Yvonne and Jeannine.

Where do you want to begin our boring pontification, sorry, our clear, fascinating and precise statement, my sometimes undecided reading friend? With Afgar, or the Andalusian Leisure? Very good. This being said (typed?), if you don’t mind, I’d rather not be forced to type the subtitle of this musical anymore. A big thank you for your kindness.

As was said (typed?) above, 3 times, Afgar was / is a musical. It originated from a slightly naughty French operetta, Afgar, ou les loisirs du harem, the premiere of which took place in 1909. Our world having changed a lot between that date and 1919, the operetta had to undergo a serious facelift before being reincarnated in the form of a rather chaste musical. If I may be permitted to paraphrase a well-known phrase, no sex please, they’re British. This being said (typed?), an actress danced in it in a costume considered indecent.

Let’s summarise the plot. Having shown a little too much charm, Don Juan, Junior was imprisoned in sight of a harem in Andalusia, the ensemble of Iberian territories under Muslim control between the 8th and 15th centuries.

Did you know that the queen and king who apparently witnessed the surrender of the last Muslim territory in Spain were the ones who financed the first crossing of the Atlantic by Cristobal Colom, an individual better known as Christopher Columbus who did not discover America? And yes, this individual who was not really a gentleman was mentioned in an August 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, but back to our plot summary.

Zaydee, the favourite of the monarch, the Afgar of the title, claimed to be madly in love with the prisoner. She convinced the other young women of the harem to start a strike on which yours truly prefers not to give too much detail. (No sex please, I’m a civil servant.) She and they asked that Don Juan, Junior be released and that every young woman get a husband. The beautiful strikers proved successful. The End.

Afgar had some success. There were approximately 300 performances in 1919-20.

Afgar also had some success in the United States. There were in fact approximately 170 performances in New York City, New York, in 1920-21. The premiere of this version took place in November 1920.

Incidentally, the New York version of Afgar was played in Toronto, Ontario, during a single week of September 1921.

All the costumes of the London version of Afgar being designed by Alexandre Paul Poiret, it would be useful to spend a few minutes to examine the career of this great Parisian fashion designer.

Poiret began his career in 1898, even before he was 20 years old. He had, however, to interrupt said career to do his military service, in the Armée de terre. In 1901, Poiret joined the staff of the most prestigious fashion house of the Belle Époque – an expression that left in the shadow the misery of the vast majority of the population of our Earth. He left the house of Worth in 1903 and opened his own fashion house in September.

Quickly known for his daring, Poiret was among the first fashion designers to get rid of the corset, in 1906. This innovation made it essential to use an undergarment invented in 1889 (?) but rarely used before the 1920s, the brassiere. Some thus saw / see Poiret as a pioneer of feminine emancipation – an exaggerated assertion, if I may. A great fashion star who was recognised on the streets of Paris as early as 1906, Poiret had multiple feminine conquests, both before and after his wedding, in October 1905.

What is it you say, my reading friend? The brassiere existed well before 1911? No? A fresco on a wall of a building in Pompeii, a city Roman destroyed in 79 during an eruption of Vesuvius? Fascinating, and tragic.

A great friend of artists, Poiret innovated in 1908 by asking a well-known artist to illustrate his catalog. He also called on another well-known artist to create fabric patterns and clothing – another innovation.

In 1910, Poiret le magnifique, as he was sometimes / often called, in French, invented the hobble skirt, a garment tightened at the ankles. The elegant ladies of the Belle Époque, including the fashion designer’s wife, however, rejected, and en masse, this daring dressiness which forced them to scamper like geishas.

Towards the beginning of 1911, Poiret invented the culotte, an innovation that proved scandalous. This outrage to public morality reached the ear of Pope Pius X, born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto, who could not help reproving it publicly. This reaction did not surprise anyone. This pope was indeed profound, dare I say viscerally, anti-modernist.

What do you say, my reading friend? The culotte existed well before 1911? No? You found an article that mentioned it in an 1896 issue of La Presse, a newspaper from Montréal, Québec? The culotte was then used by young female cyclists? How curious. Yours truly wonders if Poiret was not the one who transformed this sportswear into city clothing, to the chagrin of narrow minded people, sorry, of benevolent defenders of public morality. Anyway, let’s move on.

The lampshade tunic (tunique abat-jour in French, hello, EP!) and, more importantly, the harem pant also proved scandalous, you say, my reading friend? A big thank you for this information.

Still in 1911, Poiret launched the first fashion designer perfume – an idea that many well-known fashion designers would copy over the decades. Various accessories, from fans to samples, accompanied the delicate scents produced over the years – another idea that many well-known fashion designers would copy over the decades. Better yet, a workshop founded in 1911 produced furniture, fabrics and home decoration items that bore the name of Poiret - again an idea that many well-known fashion designers would copy over the decades.

Thanks to the support of his wife, Denise, born Denise Boulet, the ambassador of his brand, Poiret was one of the most famous fashion designers in Paris – and the world. He dressed the most famous actresses and the wives / mistresses of the most powerful men. Let us mention in passing that Poiret’s clothes were all the rage in the United States. According to some Americans, he was the king of fashion. Poiret was an avant-garde figure and a visionary, it was said, a revolutionary too. Some people who rubbed shoulders with him added, but not too loudly, that he could be a tyrant.

The Belle Époque ended in 1914, with the outbreak of the First World War. Like millions of other Europeans, Poiret was recalled to the colours. He served until 1918, but seemed to have gone through it all without serious injury.

The Paris that Poiret found once the conflict was over was a profoundly changed city. The extravagance of the Belle Époque seemed a little bit misplaced after so much horror and destruction. Many women preferred relatively clear cut clothes. Poiret had lost nothing of his haughtiness but the fact was that his best years were behind him.

It should be noted that Poiret went to New York City, in 1920. This was his first and last stay in North America. He may have designed the costumes for the American version of Afgar. Poiret discovered chewing gum before embarking on a major tour of the United States.

As spendthrift as before 1914, Poiret soon accumulated pharaonic debts. He nonetheless remained very active and creative. Poiret was one of the forerunners of the Art Déco style, a thoroughly modern one it must be admitted, for example. His participation in the Exposition internationale des Arts décoratifs et industriels, in Paris, in 1925, did not go unnoticed. Poiret presented a collection on 3 barges anchored in the heart of Paris. Their names, Amours, Délices, and Orgues, were reminiscent of the title of a Québec musical soap opera, Amour, délices et cie, mentioned in a June 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Increasingly affected by financial difficulties, the Paul Poiret house closed its doors at the end of November 1929. Tired and depressed, the fashion designer nevertheless launched one last innovation, the girdle, during the following year.

Poiret died, alone, forgotten and poor, in April 1944, at the age of 65.

This is the moment that you have been waiting with barely contained impatience, my reading friend. Yours truly will pontificate, yes, yes, pontificate, on Aircraft Transport & Travel Limited, the British air carrier that may have brought from Paris to London the models Yvonne and Jeannine, as well as the theatre costumes created by Poiret for the aforementioned musical Afgar. I shall be brief. Relatively speaking (typing?).

Aircraft Transport & Travel, say I, was born in October 1916, in the middle of the First World War. This company was a subsidiary of one of the major British aircraft manufacturers, Aircraft Manufacturing Company Limited (Airco / Air-Co), founded in 1912. Both were founded by a rich, visionary and charming businessman, George Holt Thomas. This Napoleon of the British aircraft industry as he was sometimes / often called owed his fortune to the creation of very popular magazines.

Dare I remind you that Napoléon Bonaparte, born Napoleone di Buonaparte, was mentioned in December 2017 and March 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee?

Thomas discovered aviation in 1906. Yours truly wonders if this discovery was related to the flight made in Paris in November by a rich and fearless Brazilian mentioned in November 2018, December 2018 and August 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee. On that day, Alberto Santos Dumont established the first 3 world records (distance, altitude and duration of flight) made aboard an airplane / aeroplane to be approved by the United Federation of Planets, sorry, the Fédération aéronautique internationale, the Paris-based world governing body for all manners of aeronautical records.

I venture to make this assumption given the impact of the flight of Santos Dumont on a British press mogul and friend of Thomas who was present during said flight. In fact, Lord Northcliffe, born Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, discovered a passion for aviation. Indeed, he was behind a well-known headline that appeared in November 1906 on the front page of one of his daily newspapers, Daily Mail of London: England was / is no longer an island, but back to Thomas.

I’m sure you’ll be delighted to hear (read?) that Thomas knew Richard “Dick,” Henry and Maurice Farman, the sons of the well-off Paris correspondent of a major London newspaper that still existed in 2019, The Daily Telegraph. And yes, one or the other of these brothers was mentioned in October 2018, November 2018 and August 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

A quick question if I may. How many groups of brothers who have worked in the field of aircraft manufacture can you name? I know 10: the Wrights, Voisins, Shorts, Nieuports, Moranes, Johnsons, Farmans, Caudrons, Bréguets and Borels, not to mention the Montgolfiers of course, but back to our story.

As was said (typed?) above, Airco was born in 1912. Other companies were soon added to the group controlled by Thomas: Gnome and Le Rhone Engine Company (engines), Peter Hooker Limited (engines), Integral Propeller Company Limited (propellers) and May, Harden & May Limited (flying boat hulls).

Interestingly, Thomas hired a brilliant engineer in 1914 to lead the Airco design team. This individual was none other than Geoffrey de Havilland, then aeronautical inspector at the Royal Aircraft Factory – a job that royally displeased him. Did you know that de Havilland had designed the B.E.2 observation airplane, an aircraft represented in the stunning collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa, Ontario? Better still, did you know that de Havilland was the cousin of Joan Fontaine, born Joan de Beauvoir de Havilland, an Anglo-American actress, mainly active between the mid-1930s and the mid-1960s, mentioned in a May 2019 issue our blog / bulletin / thingee?

And yes, the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum also includes examples of the de Havilland Moth, Puss Moth, Tiger Moth, Fox Moth and Mosquito.

In November 1918, when the guns fell silent in Europe and elsewhere following the signing of the Armistice, the group of aeronautical companies controlled by Thomas was among the largest in the world.

Airco founded a subsidiary in Montréal towards the end of the winter of 1918-19. Apparently devoid of a factory, Aircraft Manufacturing Company Limited of Canada seemingly did not function very long. This company worked with an equally ephemeral air carrier, Aircraft Transport & Travel of Canada Limited, a subsidiary of Aircraft Transport & Travel. Thomas was one of the largest shareholders of these 2 companies.

Aircraft Transport & Travel began a series of relief flights between the United Kingdom and Belgium in early 1919. This micro airlift organised at the request of the Belgian government actually used aircraft and pilots on loan from the British air force, or Royal Air Force (RAF). The flights apparently ended in Ghent, a beautiful city that I visited all too briefly more than 20 years ago.

At the end of August 1919, Aircraft Transport & Travel launched the first scheduled international air service, between the United Kingdom and France. The company offered a good service, despite the sometimes uncertain weather and limited capabilities of the aircraft of the time. These unsubsidized (?) flights ended at Le Bourget, near Paris, another beautiful city that I visited, all too briefly, a few times. Le Bourget was / is well known to aviation enthusiasts. It houses the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace – one of the most important museums of its kind in the world. And yes, yours truly visited this venerable institution a few times.

A regular service to the Netherlands, made on behalf of the national air carrier of that country, Koninklijke Luchtvaart Maatschappij Naamloze Vennootschap, began in May 1920.

In November 1919, Aircraft Transport & Travel obtained the first postal contract offered by the British General Post Office. Its aircraft, loaned by the RAF, flew from the United Kingdom to France and Germany.

Given that the growth of civil aviation in the United Kingdom and elsewhere did not reach the level imagined / hoped by Thomas, Aircraft Transport & Travel as well as Airco and its sister companies were almost bankrupt when he sold them, in February 1920, to Daimler Hire Limited, a subsidiary of Birmingham Small Arms Company Limited (BSA). Realising that their financial situation was worse than expected, the management of Daimler Hire placed almost all its new acquisitions in the hands of a liquidator. Thomas himself lost his seat on the board of BSA after just a few days.

Airco was put into liquidation towards the end of 1920. Aircraft Transport & Travel, on the other hand, continued its flights until December. With the air carrier going into liquidation in November when BSA decided not to pay off its debts, its assets were acquired by Daimler Hire, in early 1921, and integrated into a new air carrier, Daimler Airway Limited. The latter added its forces and assets to those of 3 other air carriers to give birth, in April 1924, to Imperial Airways Limited, the largest British air carrier of the interwar period.

It should be noted that Thomas provided some financial assistance to the aforementioned de Havilland, which enabled him to found, in September 1920, de Havilland Aircraft Company Limited, a world-renowned aircraft manufacturer mentioned in a February 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Retired in his country house, Thomas continued to be interested in aviation. This being said (typed?), he also bred Holstein-Friesian / Holstein / Friesian dairy cows. Does this name ring a bell, my reading friend? It should. This breed actually represented about 94% of the Canadian herd, which meant about 940 000 heads of cattle, in 2019.

Thomas died in January 1929, at the age of 60. He left behind many friends.

And that’s it for this week. Do not forget ... What is it I hear? You want to know what type of aircraft the models Yvonne and Jeannine may have flown in back in September 1919? I did not realise how much you cared about this kind of detail. As far as I can figure out, the aircraft in question was an Airco D.H.4 or D.H.9 single-engine bomber converted into an airliner capable of carrying 3 passengers or a certain volume of cargo.

Did you know that Laurentide Air Service Limited, a Québec and Canadian bush / commercial aviation pioneer, could count on, for no more than 3 weeks, in January 1925, a D.H.9 it had converted into an airliner? This aircraft was involved in a fascinating project, the first flight around the world, undertaken in May 1922 by 3 Britons and ... Another time, you say? All right, but back to our story.

The saga of the remarkable aircraft that were / are the D.H.4 and D.H.9 began in ... What is it I hear? You are not particularly interested in this kind of detail? I see. Very well. So that’s all for this week. You’re not much fun, my reading friend, but I will hail you anyway.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)