Never on a Sunday: The tall tale of an Iberian Roland, Part 2

Welcome back, my sceptical friend. Let us pick up where we left off. Once upon a time, in 1918 to be more precise, an aeronautical engineer at Zeppelin-Werke Staaken Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung, a subsidiary of Luftschiffbau Zeppelin Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung, designed a giant five-engined bomber made almost entirely with aluminum alloy for the German air service, the Luftstreitkräfte. (A few moments, please, so I can catch my breath. That was a long sentence and I’m not getting any younger.) Even though the signing of the Armistice, in November, brought this revolutionary project to a close, Adolf Rohrbach (1889-1939) seemingly used the work done so far to design the world’s first multi-engined all metal airliner – well, almost all metal. The four engined Zeppelin Staaken E.4/20 flew in early October 1920. Its design and capabilities deeply impressed everyone who saw it.

Claiming that the E.4/20 could be turned into a bomber, the Inter-Allied Aeronautical Commission of Control responsible for the aerial disarming of Germany after the First World War put an end to all tests. Mind you, it could be argued that the British and, even more so, the French governments wanted to cripple, if not wipe out the German airplane industry, thus removing a major competitor in what they hoped would be a burgeoning international market for civilian aircraft. Indeed, airplane production of any kind in Germany was prohibited between May 1921 and July 1922. Regulations introduced in mid 1922 meant that German companies could only produce small airplanes with limited capabilities. Warplanes of any type were forbidden. The E.4/20 stood out like a sore thumb in that brave new world.

There was much anger in German aeronautical circles when the Inter-Allied Aeronautical Commission of Control ordered that this large airplane be scrapped, which was done in November 1922. A number of aviation chroniclers / enthusiasts have denounced this action over the past decades. Such rose tinted technophilia may be misplaced. Yes, misplaced, but here and now are not the place and time to dwell upon such matters. Yours truly hopes, dare one say intends to cook up a little something on the E.4/20 before too long. But back to our story.

In 1922, Rohrbach founded Rohrbach Metall-Flugzeugbau Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung. Unable to build large airplanes in Germany because of the aforementioned restrictions, he established a company in Denmark, Rohrbach Metal Aeroplan Company Aktieselskap, where he could work in peace. As work progressed on various projects, the situation in Germany began to change. The aforementioned restrictions were eased somewhat in 1925, and abolished altogether in 1926, for civilian airplanes only of course.

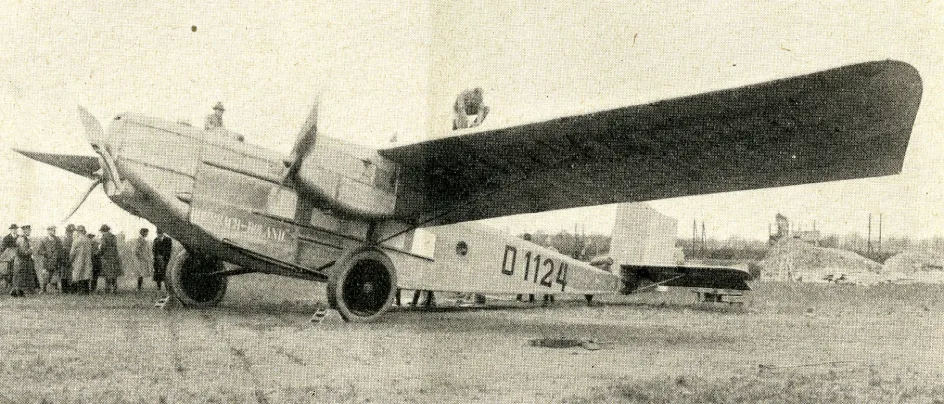

That same year, in September, Rohrbach Metall-Flugzeugbau flight tested the prototype of, you guessed it, the Ro VIII Roland (ROhrbach LANDflugzeug, or Rohrbach landplane). This 10-passenger airliner fitted with a heated and sound insulated cabin, not to mention a toilet, was loosely based on, you guessed it again, the E.4/20. Germany’s major airline, Deutsche Luft Hansa Aktiengesellschaft (DLH), accepted this airplane before the year was out. It took on strength 17 other Rolands in 1927, 1928 and 1929. Oddly enough, the pilots and co-pilots of the first six airplanes flew in the open air. Their complaints led to the installation of enclosed cockpits in Rolands built later on, and in most if not all of the ones already in service.

DLH began to operate its Rolands in 1927. As the number of airplanes in service grew, they flew to more and more important European cities, places like Amsterdam, Geneva, London, Milan and Vienna. The Roland was a solid and reliable machine with good performance. By May 1929, airplanes of this type had set no less than 22 world records (distance with load, speed with load over certain distances, etc.).

Eager to compete with a Spanish airline formed with the help of a German airplane maker, DLH chartered up to seven Rolands to Iberia, Compañía Aérea de Transportes Sociedad anónima at various times in 1927-28. These aircraft initially flew from Monday to Saturday, never on a Sunday, on a route subsidised by the German government. A passenger leaving Madrid at 8:30 AM arrived in Berlin the following day, which was pretty darn good for the time. The author of theses lines could not find the departure time of the return flight to Madrid flight. The number of weekly flights was cut to two in February 1928, just before the Spanish government took over financing of the route, but climbed back to four in April. The Madrid-Berlin route was terminated in December 1928, seemingly for lack of traffic.

As newer airliners with better performance entered service, DLH gradually began to dispose of its Rolands. A German-Soviet airline run mainly by Germans, Deutsch-Russische Luftverkehr Aktiengesellschaft, or Deruluft, got three airplanes around 1932. The last Roland operated by DLH was grounded in 1935.

You might be interested, or not, to learn that the prototype of the Roland and the airplane originally registered as M-CACA were one and the same. Soon after its return to Germany, in August 1928, this airliner was briefly and secretly / illegally converted into a military machine – presumably a bomber.

And no, yours truly has not forgotten his contention that it is possible to link von Zeppelin with Allen. You will, however, have to wait a bit more to read all about it.

More Stories by

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)