Inventing is 1% inspiration, 99% perspiration and 10% television

Hello there, my reading friend. Television is undoubtedly one of the great inventions of the 20th century. It is the best of things, it is the worst of things, if I may paraphrase Charles John Huffam Dickens. Would you care to accompany me down memory lane to look at one of the best television show you have never heard of, a story brought to you by a photo found in the 7 October 1948 issue of Photo-Journal, a weekly newspaper published in Montréal, Québec?

Once upon a time, around September 1947 to be more precise, a thin, humorous, grey haired and bespectacled British gentleman went on holiday to the south of France. This individual, Leslie Hardern, worked for Gas Light and Coke Company, a firm nationalised in 1949 and integrated within the North Thames Gas Board. He sailed away with the last group of tourists allowed to leave the United Kingdom in 1947 without having to obtain permission from the British government, and… You seem perplexed by what you just read, my reading friend. Let me explain. At that time, the United Kingdom was facing an economic crisis. To paraphrase another October 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, by the end of the Second World War, in 1945, this great power was but a shadow of its prewar self. To be blunt, the United Kingdom was pretty well bankrupt. Spending money outside the country on something as frivolous as a vacation was therefore frowned upon, to some extent, but I digress.

As he enjoyed his time away from home, Hardern became convinced that, with the United Kingdom on the ropes, British industry desperately needed new products it could export across the globe. He conceived the idea of using a brand new medium, television, to harness the inventiveness of the British people and bring it to the attention of the business community. A televised presentation by an inventor would be far more effective than a text and / or a captioned photograph. Hardern contacted the Talks Department of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). The fact that that he seemed to have worked with this government-owned broadcaster, on one or more home design shows, may have helped him get through the bureaucracy. In any event, a few influential people at the BBC were sufficiently intrigued by Hardern’s idea to launch a monthly, 30 minute show in April 1948. This television show was called The Inventors’ Club.

How were the inventions shown to viewers to be chosen, you ask? A good question, my astute reading friend, and an important one, because this selection of the ideas worthy of presentation turned out to be the biggest problem faced by the team responsible for The Inventors’ Club. As one would expect, the number of submissions grew as more people heard about the show. At some point, the team thus had to examine 200 applications each month. All of these had to include some photos and / or drawings of the invention. Even though most of the ideas came from British subjects living in the United Kingdom, inventions proposed by foreigners were equally welcome. The applications were actually opened by people other than those responsible for The Inventors’ Club. Hardern wanted to ensure that nothing improper took place. You see, when the show first hit the airwaves, some inventors offered him hard cash or a cut of the royalties to ensure that their idea got shown on television.

All in all, 40 to 50 % of the applications were quickly eliminated for various reasons (already existing commercial contracts, unsuitability for television viewing, similarity with earlier submissions, absence of commercial prospects, lack of patent, etc.). The remaining ideas were assessed by a panel made up of experts from various fields. Individuals familiar with recent inventions in certain fields could also be consulted, as required. Half of the remaining applications fell by the wayside during that phase of the process. A further examination weeded out half of the surviving applications. The people who had submitted the 20 to 30 or so ideas left in the running were invited to London to demonstrate them to an audience of journalists, inventors and BBC officials. The team chose a handful of participants from that group. It looks as if Hardern and members of the panel of experts suggested to these happy few how their ideas could be used, improved and commercialised. Hardern ran some sort of informal advice bureau that anyone with an idea could get in touch with. Any advice given came free of charge.

The president of the panel of experts for an uncertain amount of time was the president of the Design and Industries Association, Lord Sempill, also known as the Baronet of Craigevar, born William Francis Forbes-Sempill. Given the aeronautical / aerospace orientation of our blog / bulletin / thingee, you may be pleased to hear (read?) that this impetuous and obstinate First World War pilot remained interested in aviation during the interwar years. Indeed, Sempill was president of the Royal Aeronautical Society for some years during that period. If I may digress for 1 moment or 3, yours truly remembers doing some research in the library of this august institution, the oldest surviving organisation in the world dedicated to the encouragement of aerial locomotion, in the very early 1980s.

On a much darker note, and please be warned that other aspects of Sempill’s life are very dark indeed, this person was an anti-Semite who joined several far / extreme right organisations during the 1930s, as did several other British aviation enthusiasts. If I may digress again, for a few seconds, all right, many seconds, a temporary (online?) exhibition on the links between aviation and vicious 1920s and 1930s dictatorships like Germany, Italy, Japan and the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics could be very interesting – and somewhat disturbing. Such an exhibition could / should include material on aviation’s links with extremists, primarily of the far / extreme right variety, in democracies like the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Canada.

Yes, yes, Canada. Haven’t you heard of the Club d’aviation canadien Incorporé founded in Montréal, Québec, in July 1931? It may have been a tool of the Parti national social chrétien founded by Adrien Arcand, a journalist and leading figure of the far / extreme right in Canada and Québec. The club did not prove successful and may have shut down (well?) before Arcand was arrested and his party banned, in May 1940. You may remember, my reading friend, that Arcand was mentioned in a January 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, but back to Sempill.

Would you believe that this unsavoury character sold sensitive / secret information about British aircraft and other topics to Japanese officials around 1925-26 as well as around 1939-41, in other words not too long before the Japanese attacks on American and British territories in South East Asia and the Pacific in December 1941? Even though information to that effect made its way to the highest levels of the British government, no action was taken against Sempill. Prosecuting a member of the establishment, especially in wartime, while the British armed forces were being defeated by the Japanese, would have been far too embarrassing. As well, the powers that be wanted to keep secret the fact that British code breakers were reading many / most of the messages exchanged by Japanese diplomats in London, Tokyo and elsewhere. Sempill may have betrayed his country to pay some of his debts.

Another member of the distinguished panel of experts of The Inventors’ Club was a thoroughly un-creepy individual. An electrical engineer and champion of women’s rights, Dame Caroline Harriett Haslett was a director of the Electrical Association for Women, an organisation she had helped to found. Mind you, in 1948, she was also the only female member of the British Institute of Management and the British Electricity Authority. Haslett’s primary interest throughout her fascinating and multifaceted career was to use electricity to free women from household chores, thus allowing them to leave the home and pursue their own ambitions. She was the foremost British professional woman of her generation.

Oddly enough, Haslett was not a particularly good pupil. She seemed unable to sew a buttonhole. Haslett left her village before the First World War and went to London to find work. She soon joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), to the alarm of her conservative working class parents. Outraged by the British government’s continuing refusal to pass a bill that would give women the right to vote, this quasi military organisation, headed by Emmeline Pankhurst, the leading militant suffragette of the country, increasingly turned to violence to affect change. In turn, the government did little to end police brutality against suffragettes. It even instigated an appalling and unique in the world forced feeding policy for women who went on hunger strikes while in jail.

Would you mind if I put forward the idea that the British prime minister, Herbert Henry Asquith, was a narrow minded BLANK, if not BLANK SQUARED, of the worst kind? Incidentally, Haslett’s role in the WSPU’s militant campaign of the early 1910s was quite minor.

When the First World War started, in 1914, Haslett was a clerk in a Scottish boiler making company, Cochran & Company. As many male employees left for the front, under voluntarily or as conscripts, the young woman was promoted time and again. By the end of the war, Haslett ran the company’s London office. The expertise of this woman in her early 20s astonished businessmen and career civil servants who were often old enough to be her father. Cochran & Company was so impressed by Haslett’s abilities that it gave her basic training in engineering. In 1919, she became the first secretary of the recently formed Women’s Engineering Society, as well as the first editor of its magazine. Haslett’s climb to greatness was only beginning. But back to our story.

As the months went by, The Inventors’ Club became one of the most popular television shows on the BBC. Remarkably enough, it did so with precious little publicity. By 1951, more than 500 000 people watched every episode, and this at a time when the number of television sets in the United Kingdom was relatively small but growing fast (almost 764 000 in 1951 and almost 1 450 000 in 1952). Some of the people who watched The Inventors’ Club were businessmen who often called the BBC before an episode was finished, in order to get in touch with an inventor.

Hardern hosted the show as a part time endeavour. An author and successful inventor by the name of Geoffrey Boumphrey was the show’s on-air appraiser. The Inventors’ Club may have been the only BBC television show of its time to evade criticism from the British press, which was no mean feat. Oddly enough, several / many of the inventors who sent in ideas rarely if ever watched the show. Many / most of them did not even own a television set.

As of 1955, when the show went off the air, inventors had submitted more than 7 000 ideas to the staff of The Inventors’ Club. These individuals came from all walks of life, from managing directors of companies, engineers and BBC actors to unskilled workers, salesmen, housewives and farmers. Hardern presented 580 to 600 of their ideas to his viewers. In turn, more than a quarter of these ideas caught the eye of British companies. If I may digress for a moment, the number of ideas presented seems a tad high given the number of episodes of The Inventors’ Club broadcasted over the years.

Interestingly enough, The Inventors’ Club was broadcasted from the Alexandra Palace for at least part of its history. Why is this interesting, you ask, my sceptical reading friend? Well, don’t you remember that the “Ally Pally,” as this very popular entertainment destination in London was commonly called, was a place where Samuel Franklin Cody, an individual mentioned in another October 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, performed on more than one occasions? Small world, isn’t it?

Are you ready to hear (read?) a few lines on a few inventions, my reading friend? Yes, you are. Don’t deny it. The most interesting idea aired during the first episode of The Inventors’ Club was apparently an unsinkable lifeboat that worked equally well right side up or upside down. The inventor, one H.A. Gaskin, Herbert A. Gaskin perhaps, supervised the construction of a specially equipped prototype, the Green Dolphin, seemingly completed after his time on the show, which he wanted to take across the Atlantic. Although announced in newspapers in 1948, this epic journey seemingly did not take place. The same can be said of the jump over Niagara Falls, on the Canada-United States border, which Gaskin tried to organise in 1959, via his company, H.A. Gaskin Lifeboats Limited. All in all, it looks as if the Gaskin reversible lifeboat did not proceed beyond the prototype / pre-production stage.

Interestingly enough though, an American who had spent much of his life in the United Kingdom had patented an unsinkable lifeboat that worked equally well right side up or upside down no later than 1929. His name was, wait for it, wait for it, no, not H.A. Gaskin. This individual was one Thomas Herbert Gaskin. Yours truly could not find a direct link between that individual and H.A. Gaskin but I suspect that both men were related. They may even have been father and son. In any event, the elder Gaskin began to develop his lifeboat around 1906-08. This writer cannot say if it was put in production. Somehow, I doubt it.

If yours truly may be permitted to digress for 1 minute or 3, I would like to bring to your attention a little mystery that took place in August 1920 in a quiet neighbourhood of London. No, not the one in Ontario, the one in England. Unseen miscreants began to throw smooth, rounded stones of varying size at the house / villa where the inventor of the Gaskin lifeboat, as the elder Gaskin was called in newspaper reports, had lived with his family since 1906 or so. The daily bombardments took place in the evening as the Gaskins went to bed. Many front bedroom windows were broken. Gaskin’s son was even hit by a pebble. Oddly enough, the stones were not being lobbed at the residence. They were coming straight at it, more or less horizontally, as if fired by some unseen, yet powerful launcher.

Thoroughly outraged by these attacks, numerous people conducted thorough searches of the neighbourhood, with and without the help of police officers. Even though many of these individuals climbed on roofs and trees to locate the culprits, no one could see where the stones came from. If truth be told, some people keeping watch on rooftops were hit. As news of the bombardment spread, crowds gathered near the Gaskin residence evening after evening. A few days after these uncanny events began, the thoroughly baffled police officers asked for reinforcements. As a result, one evening, more than 40 policemen stood guard in the house, in the street, on roofs or in trees. Even so, the stones kept coming. The nightly attacks on the Gaskin residence seemingly ended within 1 day or 3 of this show of strength. This being said (typed?), the Metropolitan Police Service, a renowned organisation commonly known as Scotland Yard, was unable to solve the mystery. If you asked me, it’s just too bad that Sherlock Holmes was not a real person.

To paraphrase the lead singer of the American new wave band Talking Heads, in its 1981 hit Once in a lifetime, you may ask yourself why I included this tale in this issue of our oh, so very serious and well documented blog / bulletin / thingee. Yours truly must hereby and heretofore admit to a long time interest in fortean phenomena, in other words in anomalous phenomena that seem to challenge accepted scientific knowledge. The terms fortean was created in recognition of the work done by an American writer and researcher, Charles Hoy Fort, whose books were still in print as of 2018, more than 85 years after he departed from this world. And yes, the Gaskin incident was mentioned in one of Fort’s fascinating books.

Systematically poring through newspapers and scientific periodicals, this autodidact with an encyclopaedic knowledge of the world unearthed countless examples of anomalous phenomena that scientists rejected or ignored because they could not be explained. Fort exercised a healthy scepticism in his work but he liked to poke fun at the scientific establishment and its pretensions / pomposity. And I respectfully decline, my reading friend, to answer any question about whether or not I have ever been a member of a fortean organisation. On this note, may I suggest that we return to the topic at hand?

Many ideas shown to viewers of The Inventors’ Club were turned into products that could be bought in the United Kingdom and overseas. They tended to reflect the preoccupations of the time. Household inventions were especially popular, for example. About 100 men whose wives presumably loved knitting proposed various types of wool winders, for example. Close to 100 people sent in design of cinder sifters for coal fires. On a creepier note, several individuals, almost certainly men, who else would have such ideas, proposed corporal punishment machines to cane unruly schoolboys.

Speaking of men, Hardern claimed that the only good idea sent in by a female inventor was for a steam iron with 4 small retractable legs. Yours truly doesn’t know about you, but I can’t say I like that statement a whole lot. In any event, Hardern’s comment seemingly ignored a successful invention proposed by a hotel proprietress who had devised special moulds which gave exotic shapes to carrots and potatoes as they got cooked. These moulds proved do successful that she might have sold her hotel to devote her time to the design and production and bigger and better moulds. This being said (typed?), the truth was that female inventors seemingly accounted for only 5 % of all ideas submitted to The Inventors’ Club’s team. Most of these had to do with kitchen or office equipment. On the other hand, many male inventors pointed out that the idea they sent in was suggested by their wives or sisters.

Do you have a question, my reading friend? You wish to have some aviation and space content, is that it? There will be some soon, but not now. Would you like to read a fee lines on a few inventions that were put in production instead? Say (type?) no more. Here’s a brief list:

- pants whose waist could be adjusted to any size;

- a stair elevator for people with limited mobility;

- a beer bottle top which could be flipped off with any coin;

- a safety lock for motor vehicles with 10 000 combinations;

- a luminous screw driver which could be seen, and found, in the dark;

- a metal and cardboard container, or Bickle tube, used for face creams;

- home plumbing that could be detached and repaired with a tap on a lever;

- a toothpaste tube which collapsed like an accordion as it was being emptied; and

- a pig feeding machine whose mechanism reduced food consumption by 30%.

One of the successful ideas presented at The Inventors’ Club was one which seemed / seems to come up every time inventors get together. This idea was, you guessed it, an infallible / unbeatable mousetrap. Richard Evans was an engineer who designed heating plants and gigantic boilers for his employer. In the late 1940s, he began to develop a coal pulveriser for one such boiler. Evans tested his prototype in a back garden workshop behind his house. Knowing how messy and flammable coal dust was, he tested his pulveriser with rice. As a result, benches and shelves in the workshop were soon covered with rice dust. Armies of hungry mice moved in. Evans bought traps, of course, but he soon discovered that many rodents knew how to steal the cheesy bait. He also found out how painful it was to have a trap snap on a finger. There had to be a better way, thought Evans, and this how he came to invent a better mousetrap.

Featured on The Inventors’ Club in late 1949, said trap did not go unnoticed. Several businesses contacted Evans who politely turned down their offers. He chose to form a small company which farmed out production of the trap. Within a few months, the light engineering firm Evans had signed a contract with was making 5 000 mousetraps a week. Within a year, he was considering the possibility of selling production licenses in places as far apart as the United States and New Zealand. Yours truly does not know if Evans concluded any deal. Incidentally, he kept his day job. One did / does / will not get rich making and / or selling mousetraps.

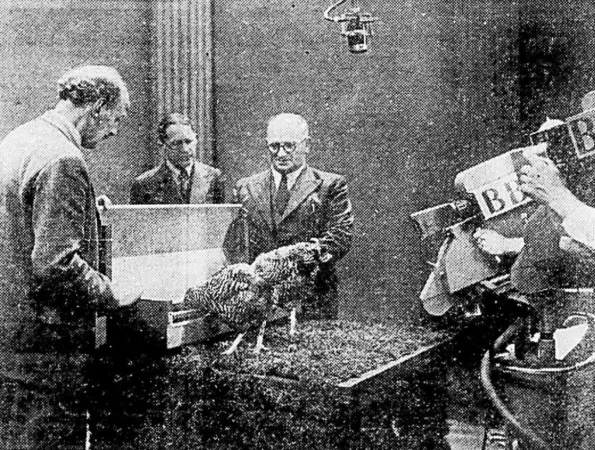

And yes, my reading friend, the chicken feeder whose image can be found at the top of this article was put in production. Designed by a poultry farmer, this wild bird and rat puzzler, as it was informally called, included a square section metal bar whose rotation so unsettled the aforementioned pests that they left the chicken’s food alone. The feeder thus paid for itself within a short period of time. Oddly enough, the rotating bar did not unsettle the chicken, as the people watching a 1948 episode of The Inventors’ Club where the feeder was demonstrated could clearly see. The strange surroundings and the television cameras did not seem to unsettle the chickens too much either. The inventor of the feeder seemingly had 1 000 of these devices made before his appearance on The Inventors’ Club, to fulfill unsolicited orders by people who had heard of his invention. His appearance on the show led to thousands of additional orders from all over the United Kingdom.

Yours truly would now like to present some of the inventions that were put though their paces during various episodes of The Inventors’ Club but failed to achieve production. In some cases, an apparently worthwhile idea failed to catch interest. In others, the invention was just, well, a tad too nutty. In any event, please find enclosed some inventions that caught my roving eye:

- an electric dog to scare away burglars;

- roller skates especially designed to roll uphill;

- hand lights for cyclists to indicate turns at night;

- an armchair which turned into a bed in 4 seconds;

- a pedal-operated electric page turner for musicians;

- a foot warmer for people allergic to hot water bottles;

- a napkin which clung to a baby without any safety pin;

- a device, known as the ionette, which ironed out face wrinkles;

- a hand cream which turned dirt into small balls that just fell off;

- a small electric car which housewives could use to do their chores;

- a yoke that automatically locked the head of a cow feeding at a trough;

- gloves with a transparent panel on a wrist, where one would wear a watch;

- a plughole which allowed the water in a bathtub to run off without gurgling;

- a trumpet silencer with an internal microphone and earphones for the player;

- a milk bottle holder which protected them from animals and careless children;

- a small motor which used the opening and closing of doors to produce energy; and

- a washing machine which could also wash and dry dishes, peel potatoes and mix dough.

Another neat idea, if I may say so, was a combined automobile and motor boat. Upon arriving at a marina in his specially-designed car, the proud owner drove his vehicle onto the deck of his boat. The steering wheel and driving axle of the automobile then coupled with the rudder and propeller of the boat. The aforementioned owner could then sail away without leaving his seat.

Interestingly enough, a combined automobile and motor boat was unveiled in January 1958 at the Mid-America Boat Show held in Cleveland, Ohio. The motor boat was developed by Seamobile Corporation of Cleveland. It was named William T. Sweeny, after a well known Great Lakes shipbuilder who had died in 1932. From the looks of it, this combined automobile and motor boat was not a commercial success. Yours truly cannot say if this vehicle was inspired by the proposal submitted to The Inventors’ Club and… What’s this? You don’t believe me? Shame on you, my doubting Thomas reading friend. Please note that this information was culled from the pages, page 2 more specifically, of the 9 November 1958 issue of L’Action catholique, a daily newspaper from Québec, Québec.

In some cases, yours truly could not determine whether or not an idea was put in production. One of these was a clothes line that did not require the use of pins. Developed by a married couple, it consisted of 2 ropes twisted together and held taut. Clothes in need of drying were simply slipped through the ropes. A foldable ironing board with a built-in seat was another idea for the home. The board could be used as a desk. Another invention was an automatic dance instructor. Students standing on a raised sheet of glass placed their feet on footprints projected by lights placed below it. The colour of the footprints varied depending on the dance step, as did the speed of their appearance. Flashing arrows warned the students that a step was about to appear.

An 8-wheel baby carriage proposed by a Czech gentleman in 1948-49 was also worth mentioning. The configuration of the 6 wheels at the rear kept the carriage horizontal in all circumstances, whether going up a flight of steps or coming down a hill. Yours truly had the pleasure of finding a photo of this baby carriage.

The baby carriage proposed by the Czech gentleman. Anon., “Moins d’efforts pour la maman.” L’Action catholique, 22 January 1949, 7.

According to the font of all knowledge, Wikipedia, the tri-star wheel configuration found on the baby carriage was developed in the United States in 1967, by 2 Lockheed Aircraft Corporation engineers. The photo published by L’Action catholique morethan 15 years before thoroughly invalidates this statement. Nowadays, one of the most common applications of the tri-star wheel configuration appears to be in stair climbing devices for people with limited mobility. The most spectacular application of this configuration was undoubtedly the Landmaster, a massive and unique amphibious vehicle designed and built for the 1977 science fiction film Damnation Alley.

A 15-year old inventor caused quite a stir in the summer of 1952. John A. Lowrie was to appear on The Inventors' Club to present a most original, dare one say revolutionary double-decker bus design. The teenager put the engine of his bus at the back, which allowed him to lower the floor and roof without reducing headroom. The British Transport Commission was so impressed that it agreed to have one of its experts question Lowrie before the cameras. It also asked one of the nationalised companies under its control, Bristol Tramways & Carriage Company, to cooperate – and that’s when the proverbial you know what hit the fan.

You see, my reading friend, engineers working for that well known and respected manufacturer located in, you guessed it, Bristol, England, had been working on a similar bus design since 1949, without too much success. They did not wish to be held up to ridicule by a teenager. As a result, the head of Bristol Tramways & Carriage refused to abide by the request of the aforementioned commission. Whether or not this individual changed his mind, voluntarily or otherwise, is unclear. Yours truly can only presume that Lowrie presented his design during a 1952 episode of The Inventors’ Club.

Would you believe that Lowrie won a national engineering prize before the age of 20? As you may have guessed by now, he became an engineer. This exceptionally gifted individual joined the staff of Nottingham City Transport in the late 1950s. A very advanced double-decker city bus he designed for this organisation proved very successful. Lowrie eventually became engineering director at Nottingham City Transport Limited, as the city’s public transit organisation was called after its privatisation in 1986. He retired in 2002 but did not remain idle. Lowrie spent some time developing diesel (and gasoline?) engine technologies with engineers and researchers in academia and industry.

Do you have a question, my reading friend? Oh, yes, aviation and space content. You are persistent, I’ll give you that. After much searching, yours truly thinks he has a little gem for you, my sometimes annoying reading friend. Arguably the most innovative and unusual idea proposed to The Inventors’ Club team came from an elderly gentleman who had invented a very special powder. Before going aloft in an airplane or helicopter, a person only needed to put some of this powder, whose ingredients were a well kept secret, in her or his pockets. If an in-flight emergency occurred, this person only had to step off the aforementioned airplane or helicopter in order to float down to earth. Thoroughly intrigued by this remarkable idea, Hardern asked the inventor if he would be willing to demonstrate it by stepping off a window on the sixth floor of a building, presumably that of the BBC. The elderly gentleman emphatically refused. And no, his invention was not shown to viewers.

The last episode of The Inventors’ Club went on the air around 1955. You may be pleased to read, or not, your choice, that this television show inspired the development of a French version. Broadcasted by Radiodiffusion-Télévision française, the Club des inventeurs was a 30-minute weekly show aired during an as yet undetermined number of years during the 1950s. Any information you could find on that Gallic gem, my reading friend, would be most welcome.

Would you believe that the idea behind The Inventors’ Club proved far more popular in Australia than in its home and native land? Produced by the government-owned Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), The Inventors hit the airwaves in 1970. Launched as an unimaginative low budget summer fill-in, this weekly half-hour show became one of the most popular television shows in the land down under. More than 60% of the hundreds of inventions presented to its viewers made it to production. The final episode of The Inventors was broadcasted in 1982. By then, a private channel, Nine Network, a subsidiary of Nine Entertainment Company, had created a competing show which superseded its rival, thanks in part to its use of members of its evaluating panel, poached for that very purpose. What’ll They Think Of Next? ran for an as yet undetermined number of years. Would you believe that a descendant of ABC, ABC1, launched The New Inventors in March 2004? This very popular weekly half-hour show lasted until August 2011. Australians do seem to like their inventors, don’t they?

Yours truly wonders why government-owned broadcasters like the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and its French language counterpart, the Société Radio-Canada, seemingly never produced a show like The Inventors’ Club.

A bit more could be said (typed?) about these French and Australian shows, the inventions and the various members of the evaluating panels but my typing fingers, all 2 of them, are tired. So, profuse apologies for this unusually long and verbose text. Would you believe that yours truly considered dropping this topic because I feared there might not be enough information available? Anyway, I wish to thank all the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, not theirs. Ta ta for now, mate.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)