Mind the gap: The positive impact of multi-sensory experiences

As a child, I always seemed to be on security’s radar at art galleries and museums. And so, I should’ve been. Whether it was a Group of Seven at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection or a 2,000-year-old mummy at the Royal Ontario Museum, my warm breath was just inches away — trying to get a closer look at brushstrokes and details. My 10-year-old nose and brow was always pressed up against a glass showcase, trying to make out the markings on a sarcophagus.

As a blind/low vision child, two things I loved always seemed to be just out of reach: history and art.

At the end of the day, I was just happy to be there. Any school trip to a museum, art gallery, or science centre was more dynamic than sitting in a classroom, waiting for a “large print” textbook that wouldn’t arrive until halfway through the year. Or sitting through a lesson that I couldn’t see.

As a girl with a disability, nobody was really pushing me towards science, politics, or history...even though I always had lots of questions about them. Art meant that once a week, somebody was finally interested in what I saw or how things looked from my perspective. I could touch it. It wasn’t something far away on a chalkboard, or in a book I couldn’t read. It was literally in my hands.

It was through the world of art that I found my voice. As for history and social sciences, I found myself learning about stories that I could actually relate to. Even though I didn’t have the vocabulary for discrimination, I certainly knew what it felt like. I didn’t know it at the time, but I grew up in a school system that just wasn’t ready for me (yet).

Needless to say, there is a gap in our education system when it comes to multi-sensory learning. What I love about art galleries and museums is that they help to bridge part of that gap. It’s the teachers who work with local museums to create a different experience for their students that really make a positive impact.

Many people assume that visual learning dominates the classroom because it is the sense that provides us with the most information. This is incorrect; vision is intended for providing us with the quickest overall assessment of a concept or situation. But it is by no means the only, or even the best, way of presenting new information.

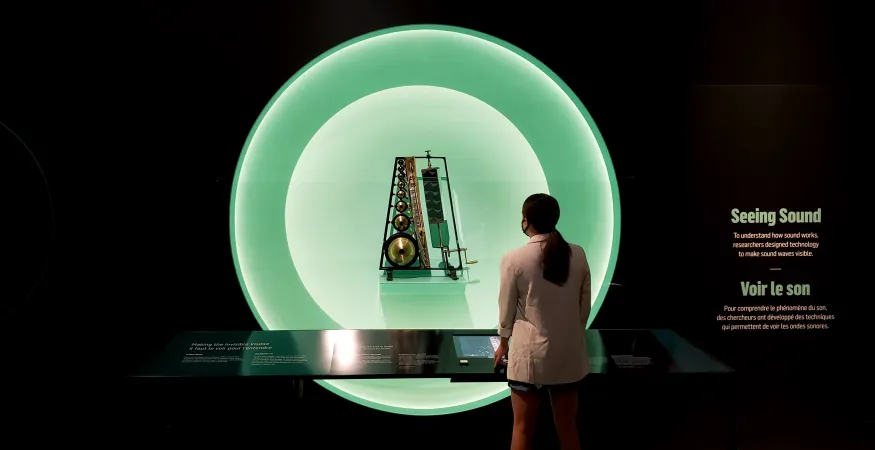

This got me thinking, how can we expect to be the best versions of ourselves if we’re only using one sense to learn and understand information? After all, we have five! Why not use a variety of them to learn? This is something that is reflected across Ingenium – Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation in Ottawa.

This past summer, I had the pleasure of working on accessibility guidelines for the creation of presentations and images with Curator of Communications Tom Everrett. We started with the basics: alt text. Alt text is what appears on a webpage in place of an image that won't load, and it’s also used as an accessibility feature. Alt text allows screen readers and software used by the blind and low-vision community to navigate images.

Writing alt text for images requires us to look at how we label people — and why. It's one thing to provide the specifics of an object, such as the make and model of an aircraft. Things like the age, race and gender of a person is another. However, these details are important — especially in a historical context. Labels scare us because we know they have a history of being used negatively. Racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism, and colonialism are just a few of the reasons why we have all grown to hate labels.

Like water, labels can give or take away life. We can drown in them, or choose to be nourished by them. Even though I would love to say living in a world without labeling could be beautiful, labels are part of our identity; they help us track progress through history. It allows us to see our mistakes and learn from them.

Alt text is simply a way of conveying the same message a visual image provides, but in an audio format rather than a visual one.

The second area of my work with Everrett focused on presentations. We examined presentations between Ingenium staff, and the idea of incorporating accessibility and multi-sensory learning from the beginning of the curatorial phase. This tied in closely with research instigated by Carla Ayukawa, a Curatorial Studies practicum student. In her research paper, “Experiences and Methodologies in Working with People with Impaired and Low-Vision to Create Content for a Virtual Exhibition,” Ayukawa explains how incorporating people with blindness or other disabilities in the early phases of curating a museum collection can make the exhibit inherently more accessible.

In no way do I have all the answers on how to make everything accessible to everyone — in the most socially conscious way. But I want to try. As time moves on, someone will look at my initial guidelines and see how they can be made better!

True innovation can’t occur without diversity. People from all walks of life are needed to create exhibitions where everyone is able to fully immerse themselves in the same experience, but in a way that’s unique to them. This will bring us a truly innovative future…a future that one day I hope to see.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!