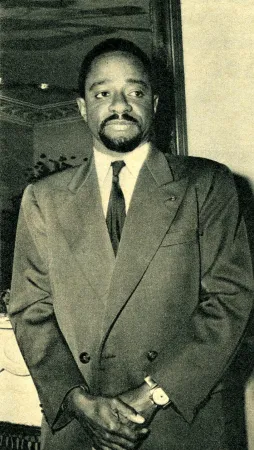

An exceptional pilot, Charles Yves Joseph Éboué

Greetings and welcome, my reading friend. Yours truly came across this week’s story quite by chance, which is not necessarily a good thing. I should have noticed it during my first look at the 1 March 1958 issue of the French bi-monthly Aviation Magazine, an excellent publication if there was one. A publication, dare I say, that allows us to approach the evolution of aviation and spaceflight from a point of view that is not American or British - or Anglo-Canadian. But back to our story.

We are in May 1924, in Afrique équatoriale française, a federation of the 4 French colonies in Equatorial Africa (Chad, Gabon, Middle-Congo and Ubangui-Shari). The wife of the subdivision chief Adolphe Sylvestre Félix Éboué, born Eugénie Tell, gave birth to a third son. This child, Charles Yves Joseph Éboué, was attracted by aviation from an early age. He started making models before he was 10, for example. A pilot who flew from Paris to Tōkyō, with a mechanic, between April and June 1924, George “Pivolo” Pelletier d’Oisy, took the boy with him in 1935. Subjugated by this first flight, Éboué declared to his parents that he wanted to become a pilot. They did not agree.

Éboué senior was a fascinating character. Appointed governor, 2nd class, in Chad, in 1938, he was the first “native,” a pejorative term if there was one, to obtain a position of governor, the highest of the French colonial administration. Éboué was both a symbol of a civilizing mission that was too rarely sincere and an agent of a colonisation that was too often brutal. In any event, he was still in office when France collapsed in June 1940, under the blows of the German armed forces. Incapable of accepting this defeat, Éboué contacted a person equally unable to accept this defeat, the founder of Free France, Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle, as early as July and rallied to him. Chad became the first territory of Free France in August. Éboué himself became governor general of Afrique équatoriale française in November.

Sent to Cairo to continue his studies, Charles Éboué obtained permission from his father to register at the Aéro Club d’Égypte, after obtaining good grades in mathematics. Increasingly fascinated by flight but aged 18, thus still a minor, he obtained permission to join the Forces aériennes françaises libres in 1942. Éboué was one of the first, if not the first African pilot in the French armed forces.

The young man began pilot training in 1943 at a Royal Air Force (RAF) elementary flying training school in the United Kingdom. He pursued it in Canada even before the end of the year, at No. 31 Elementary Flying Training School, in De Winton, Alberta. Éboué completed his training in October 1944 at No. 34 Service Flying Training School, in Medicine Hat, Alberta. These two schools were part of the very large British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, one of Canada’s major contributions to the Allied victory in the Second World War. Éboué’s success, however, was tinged with terrible news. His father died in May 1944. The young pilot later found himself in two RAF operational training units in the United Kingdom. In all likelihood, Éboué joined a combat unit, the Groupe de Chasse 1/2 “Cigognes” of the Forces aériennes françaises libres, or No. 329 Squadron of the RAF, only around July 1945, about two months after the unconditional surrender of National Socialist Germany.

Still fascinated by flight, Éboué completed a commercial pilot course at the training center of the Compagnie nationale Air France. Hired in 1948 by a private air carrier, the Société de transports aériens, he flew Douglas DC-3s used for the transport of early vegetables to various European countries (Italy, Spain, Sweden and United Kingdom). After some time spent flying in Afrique équatoriale française, Éboué joined the ranks of Société Aigle Azur in 1951. Promoted a captain, he made many flights over the Fédération indochinoise, a grouping of the 5 French territories of the region (Annam, Cambodia, Cochin China, Laos and Tonkin), then torn apart by a war of independence lost by France in 1954. The young pilot returned to France in 1952 and was assigned to long-haul flights, to Afrique équatoriale française and the Fédération indochinoise for example. And yes, my reading friend, the excellent collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, includes a DC-3.

Éboué remained in place at the time of the merger of Aigle Azur with another private airline, the Union aéromaritime de transport, in 1955. He also stayed put in 1963, when the latter merges with the Compagnie de transports aériens intercontinentaux, another private air carrier which then became the Union des transports aériens Société anonyme à participation ouvrière.

Éboué became a jet pilot around 1963. Over the years, this energetic, generous and laughing family man piloted very well-known airliners: Douglas DC-8, McDonnell Douglas DC-10 and Boeing Model 747. By then a major figure in French commercial aviation, he retired around 1984, after about 35 years of civilian flying. Charles Yves Joseph “Charly” Éboué died in France in December 2013, at the age of 89.

The author of these lines wishes to thank all the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, not theirs.

More Stories by

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)