A racing airplane made in Paris by unemployed workers

Hello comrade. (Hello, CF!) I invite you today to another journey in time and the wonderful world of aviation and space. Our goal is a dead end at the end of a Paris street that you have never heard of, Angoulême Street.

Interestingly, at least for yours truly, the city of Angoulême, in the south of France, had / has among its many attractions the Festival de la Bande Dessinée d’Angoulême and the Cité internationale de la bande dessinée et de l’image. I had the great pleasure to visit the museum and library of the latter in 2010. Indeed, I must confess I am fascinated by the history of comics, one of my many faults.

Given the circumstances, you will understand how pleased I was to participate, quite modestly I must admit, in the realisation of a temporary exhibition on a comic book hero mentioned in September 2018 and March 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee. In 1994, a quarter of a century ago (!), the National Aviation Museum, today’s Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, offered Dan Cooper: Canadian Hero to its visitors. (Hello, MD!) A few other Canadian cultural institutions later presented this fascinating exhibition about the eponymous fictitious Canadian fighter pilot, made with the help of various organisations, but I digress, another of my many faults. Sorry.

This being said (typed?), would not it be interesting to design a (international?) traveling exhibition on comics and aviation and / or space? Just sayin’. Tintin, a world-famous paper hero created by Belgium’s Hergé, born Georges Prosper Remi, was / is an excellent pilot, they said / say, but I digress. Again. Darn. And yes, both Tintin and Hergé were mentioned in some issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since July 2018.

Now, the topic of this week of our blog / bulletin / thingee came from the 2 August 1939 issue of the Paris daily newspaper Ce Soir, created in March 1937 by the Section française de l’Internationale communiste. Prohibited from publication between the end of August 1939 and August 1944, this general information daily which wanted to be popular in every sense of the word has not yet been used by yours truly as part of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Our topic of the week is focused on a French aircraft designer. Max Holste saw the light of day in September 1913. His father, a pilot during the First World War, disappeared in combat when he was only 2 years old. His mother having to raise her son alone, the little family did not roll in money, far from it. A maternal uncle, his godfather in fact, brought Holste to Paris around 1925-26. Raymond Saladin, a journalist who has been interested in aviation for several years, said he was ready to help him get settled. Holste then thought of becoming a doctor. He began to become passionate about aviation around 1927-28.

Holste enlisted in the Aéronautique navale, the air force of the French Marine nationale, as the early age of 18. Once his training was over, he was assigned to an airport in the Paris region. His free time allowed him to study. Yours truly unfortunately does not know if Holste took high-level courses in any institution. Holste subsequently designed its first aircraft, a light / private 2-seat airplane. Returning to civilian life in 1934, he founded the Société des avions Max Holste and built his aircraft in the workshops of a Paris coachbuilder. Not having the funds to pay the insurance premium, he had to give up seeing his small monoplane fly.

Holste briefly worked with a Belgian aristocrat, Count Pierre Louis de Monge de Franeau, which was / is a bit curious. Indeed, a brief research revealed that this designer was then chief research engineer at Imperia Automobiles Société anonyme, a Belgian car manufacturer. Be that as it may, Holste later worked at Avions Henry, Maurice and Dick Farman, a well-known French aircraft manufacturing firm.

Around 1938, Holste found a job as a research engineer in the aeronautical division of the Société d’emboutissage et de constructions mécaniques, a firm better known as Amiot. He spent his free time designing a racing plane capable of breaking the speed records of the elegant machines of the Société des avions Caudron. In late 1938, early 1939, Holste decided to build his aircraft in order to engage it in the 1939 edition of the competition that the machines of said Caudron company won from 1934 to 1936, the Coupe Deutsch de la Meurthe. To do this, he did not hesitate to leave his job, much to the regret of his employer.

Does the name Deutsch de la Meurthe ring a bell, my reading friend? No? Let me enlighten you. Henry Deutsch de la Meurthe, born Salomon Henry Deutsch, was a French industrialist / entrepreneur, patron and composer. Passionate about technology and, especially, aviation, this oil magnate participated in the founding of the Automobile-Club de France (1895) and the Aéro-Club de France (1898). Deutsch de la Meurthe was actually president of the latter between February 1913 and November 1919.

In April 1900, Deutsch de la Meurthe offered a large sum to the first flying machine capable of making a round trip of about 10 kilometres (about 6 miles) between an area of Paris and the Eiffel Tower in less than 30 minutes, and this before October 1904. Alberto Santos Dumont, a rich and fearless Brazilian mentioned in November and December 2018 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, achieved the feat in 29 minutes and many seconds in October 1901.

In 1904, in concert with another aviation enthusiast, Deutsch de la Meurthe offered a smaller sum to the first person who would fly 1 kilometre (about 0.6 mile) in a closed circuit aboard an airplane / aeroplane. A British, yes, yes, British, subject, until 1937, who lived in Paris, Henry Farman, mentioned in an October 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, achieved the feat in January 1908. And yes, this Farman was the Farman mentioned above. Small world, isn’t it?

Would you believe that it was the Compagnie générale de navigation aérienne cofounded by Deutsch de la Meurthe in 1908 which organised the demonstration flights made in France by Wilbur Wright from August 1908 onward? And yes, Wright was mentioned a few times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since December 2017. The important thing here, however, was to note the impact of the flights of Wright, who became a hero everywhere in France and well beyond.

In 1909, Deutsch de la Meurthe created an international speed competition, the aforementioned Coupe Deutsch de la Meurthe. The 1939 edition of this competition would be held on 1 October, but back to Holste and his project.

At the end of January 1939, the Aéro-Club de France received a first commitment for the 1939 edition of said Coupe Deutsch de la Meurthe. And yes, you are quite right, my reading friend, this commitment was sent by Holste. Aeronautical circles were surprised. Indeed, virtually no one knew the young designer. Eight other registrations reached the Aéro-Club de France before the end of the commitment period. Would you believe that one of the registered aircraft, the magnificent Bugatti 100, was designed by the aforementioned Count de la Monge de Franeau? Small world, isn’t it?

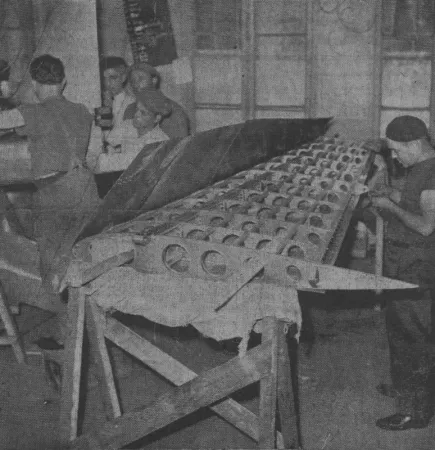

Thinking about making a wooden racing airplane, Holste contacted the École de rééducation et de perfectionnement professionnels of the Union des syndicats des travailleurs de la métallurgie de la région parisienne of the Confédération générale du travail (CGT) to see if it was able to manufacture some metal parts, such as the engine mount. This modest Parisian school, inaugurated in May 1937, gave him such a warm welcome that he finally decided to make an all-metal aircraft.

The École de rééducation et de perfectionnement professionnels offered training in various fields (adjusting, grinding, milling, planing, turning, etc.) related to the metal trades and, more particularly, to the aircraft industry to unemployed men who had successfully completed an interview and a 15-day trial period. Said training lasted from 2.5 to 4 months, at a rate of 5 days a week. A typical day consisted of 6 to 6.5 hours of manual work and 1.5 to 2 hours of theory (algebra, arithmetic, calculus, geometry, trigonometry, as well as labor law and social legislation). Each student received a small amount of money each day. The school also offered refresher courses every night and Saturday all day. By the summer of 1939, it had about 600 students ranging in age from little more than 20 to slightly more than 60 years of age. Some of these actually participated in the construction of a second workshop, which had become necessary to meet demand.

By the summer of 1939, the staff of the École de rééducation et de perfectionnement professionnels had trained about 1 100 unemployed men. As an exit bonus, all these people received the tools they had used during their training. The quality of said training being widely recognised, including within the Ministère du Travail, applications for admission increased at such a rate that the institution had to multiply the number of machine tools. The number of work shifts also went from 1 to 3.

It should be noted that France had fewer than 15 or so vocational rehabilitation centres. Only the École de rééducation et de perfectionnement professionnels owed its origins to the trade union movement. Interestingly enough, it apparently trained as many unemployed men in a year as all other vocational rehabilitation centres combined. The École de rééducation et de perfectionnement professionnels seemed to be the only rehabilitation centre that trained workers capable of working in aeronautics.

Let me underline that the enthusiastic reception given to Holste by the management of the École de rééducation et de perfectionnement professionnels was obviously not disinterested. The Union des syndicats des travailleurs de la métallurgie de la région parisienne wished to make its school, an innovative social achievement if there was one, known and to make people realise the quality of the training offered there. The construction of the MH-20 allowed school students to gain practical experience at the end of their training.

The union also hoped to highlight the many political and monetary hurdles that the government was placing in its path. If approximately 875 students managed to find a job between May 1937 and April 1939, many others were turned away, and this at a time when the French aircraft industry was trying by all means to increase its rate of production. Some aircraft manufacturers seemed to fear the militancy of workers trained at the École de rééducation et de perfectionnement professionnels. Worse still, the government did not give the school the sum of money it was entitled to as a vocational rehabilitation centre. It even dared to ask the school management to eliminate 1 of its 3 work shifts.

The Union des syndicats des travailleurs de la métallurgie de la région parisienne, finally, was not without knowing that the victory of an aircraft made by unemployed men, in a school created by the trade union movement, against aircraft manufactured by private industry, in the context of a race sponsored by a rich capitalist, would have a non-negligible symbolic, even political, impact.

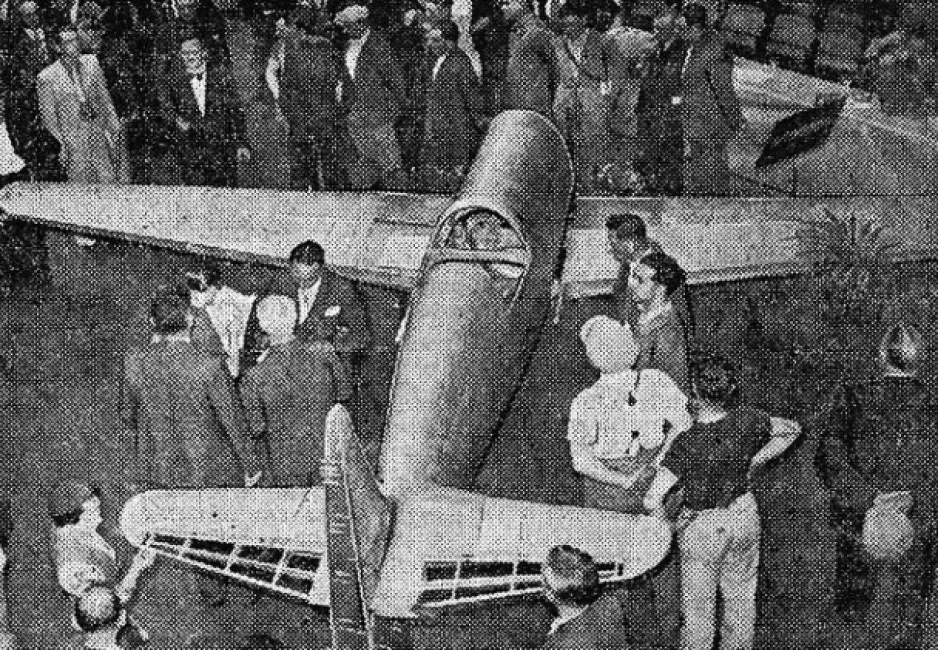

The plans of the MH-20 began to take shape in January 1939. The construction of this fine and racy aircraft began in March. At the end of July, the union invited the press, both general interest and aeronautical, to come and see the MH-20, still incomplete, at the beginning of August 1939, at the Maison du métallurgiste, a place of trade union culture and struggle which contained a library, a coop and classrooms. Many journalists, union activists and political personalities responded to the invitation. Holste answered their many questions. The enthusiasm of the young engineer and of the management of the school was contagious. Many journalists published articles on the MH-20.

The Holste MH-20 during its presentation to the press and union activists, August 1939, Paris. Anon. “Construit par les élèves de l’école de rééducation du syndicat des métaux...” L’Humanité, 3 August 1939, 1.

Representatives of the CGT took the opportunity to promote the École de rééducation et de perfectionnement professionnels and defend the Union des syndicats des travailleurs de la métallurgie de la région parisienne, attacked by newspapers and businessmen who hardly appreciate the fact that its management seemed very close to the Section française de l’Internationale communiste.

In order to take part in the Coupe Deutsch de la Meurthe, the MH-20 had to qualify before 15 September. Its pilot, presumably Marcel Finance, a monitor at an aerodrome near Paris, had to fly 500 kilometres (about 310 miles) at an average speed of 350 kilometres/hour (about 217 miles/hour). The engine ordered by the ministère de l’Air being late, Holste and his team were slightly nervous. In fact, said engine did not begin its homologation tests until August 1939.

A detail if I may be permitted. Finance should not be confused with Marcel Finance, a young pilot in the Armée de l’Air, the French air force, who served in the Forces françaises libres during the Second World War. The latter died in service in April 1943, at the age of 24. But back to our story.

Holste also thought about what his aircraft would do one after the holding of the Coupe Deutsch de la Meurthe. An actress, automobile pilot and aviatrix, Viviane Elder, born Eugénie Anne Marie Madeleine Hignette, would try to seize the speed record for female pilots then held by the American Jacqueline “Jackie” Cochran Odlum, born Bessie Lee Pittman.

I will not tell you anything you did / do not know by saying (typing?) that Cochran used a North American F-86 Saber fighter to set speed records in May and June 1953 (100 and 500 kilometres (about 62 and 310 miles) closed circuit speed; and pure speed over a distance of 15 kilometres (about 9 miles)). This being said (typed?), did you know that this aircraft was Canadian made? Yes, yes. More exactly, it was Québec made. Manufactured at Canadair Limited’s Cartierville shops, this Saber was the first aircraft powered exclusively by an Orenda turbojet, an excellent Canadian-designed engine manufactured by the Gas Turbine Division of A.V. Roe Canada Limited (Avro Canada) in Malton, Ontario. This specially modified aircraft took to the sky in October 1950. It was the direct ancestor of the Orenda powered Sabres that Canadair manufactured between 1953 and 1958. And yes, my reading friend who is fascinated by small details, the amazing collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum includes 2 Sabres.

I would like to note that Canadair and Avro Canada were subsidiaries of Electric Boat Company and Hawker-Siddeley Aircraft Company Limited / Hawker Siddeley Group Limited, respectively. As we both know, all of these companies are mentioned a few times in our blog / bulletin / thingee, and this for ages. With this digression over, let’s go back to Holste and the MH-20.

France having declared war on Germany in September 1939, following the invasion of Poland, the 1939 edition of the Coupe Deutsch de la Meurthe was canceled. Some hoped that a race would take place in 1940. The staff of the École de rééducation et de perfectionnement professionnels seemingly completed the MH-20 around September / October 1939. Very interested in the simplicity and robustness of this aircraft, the technical service of the ministère de l’Air asked Holste to present a version usable for training.

The collapse of France in June 1940 put an end to the training airplane project and to any hope of holding any race whatsoever. Holste and his team dismantled the MH-20 and stored it before the arrival of the German armed forces in Paris.

In 1941, representatives of the German air force, or Luftwaffe, proposed to various aircraft manufacturers and designers to test prototypes set aside since the defeat of France. Holste accepted this offer despite the fact that his aircraft would have to carry German identification markings. The aforementioned Finance received permission to do taxi tests, and no more.

To everyone’s surprise, he put the pedal to the metal and took to the sky. The engine of the MH-20 failed a few minutes later while Finance ran a circuit around the airfield. Too low to reach it, he had to land at high speed and from the side on a concrete runway under construction. The MH-20 stopped on the stony approach of the site. It had lost one leg of its landing gear and had a damaged wing. Finance, who did not seem to be hurt, got royally bawled by Luftwaffe observers. He was not, however, put in jail. The MH-20, on the other hand, went into a hangar. Holste was devastated.

As the Second World War continued to rage, Holste found himself involved in a rather unusual project: the production of a Henry Farman Model 1911, or Henry Farman III, used in the filming of the feature film Le Mariage de Chiffon. This comedy drama told how a teenage aristocrat who rejected the established order, Corysande de Bray, known as ‘Chiffon,” managed to marry the man she loved, the brother of her father-in-law, a ruined pioneer of aviation much older than she – a central theme that makes yours truly feel rather uncomfortable.

Said pioneer of aviation having to fly an airplane, if only through a stand in, the director of the film asked a well-known pilot of the Belle Époque, Louis Gaubert, to find a builder able to make a reproduction of said Henry Farman III. The aforementioned Saladin recommended to the latter to use his godson. Gaubert saw no objection, and neither did the director. If the lack of plans and the scarcity of the materials needed, mainly wood and fabric, caused a lot of headaches to Holste and his team, they nevertheless managed to fulfill their order.

Antoine Marie Charles de La Chapelle, an Armée de l’Air pilot who had destroyed 7 German aircraft in 1939-40, made 2 hops on the same day, in June 1942, under the watchful eye of the film crew’s cameras and the applause of extras in period costume. The aforementioned Farman was present. In fact, he got permission to sit on the pilot’s seat. Small world, is it not?

The premiere of Le Mariage de Chiffon was held in September 1942. Critics of major Paris newspapers seemed to enjoy this feature film.

The company which produced Le Mariage de Chiffon graciously donated the Henry Farman III to Holste at an indefinite date. He in turn gave the aircraft to an association that included pilots who had received their license before the start of the First World War, in August 1914, the Vieilles Tiges. Everyone involved hoped that the fragile biplane, temporarily disassembled, would fly at least once again after the end of the Second World War – a dream that did not seem to come true. Would you believe that the Association amicale de pionniers, pilotes et amis de l’aviation still existed in 2019?

Interestingly, at least for me, eccentric that I am, Le Mariage de Chiffon was / is an adaptation of the eponymous novel, published in 1894, by a well-known woman who operated a salon and a prolific novelist (about 115 largely forgotten works between 1882 and 1931) of the Belle Époque, the wife of Count Roger de Martel de Janville, born Sibylle Marie-Antoinette Gabrielle Riquetti de Mirabeau, known as “Gyp”. Le Mariage de Chiffon was / is one of the major works of this hyper-nationalist and anti-Semitic right-wing anarchist. Let us leave this sulphurous person to return to Holste and his other projects.

In June 1944, 2 bombs dropped during an Allied raid on Paris pulverised Holste’s workshop and its contents. The MH-20, a glider almost ready to fly and the fuselage of a single-engine light / private airplane, not to mention all the young designer’s records, were destroyed in the fire that followed this attack. Holste refused to let himself be defeated, however,

Once the Second World War ended, Holste began designing some single engine light / private airplanes. One of them was produced in very small numbers around 1946-47. A rustic utility aircraft, dare one say the French equivalent of the de Havilland Canada DHC-2 Beaver bushplane, flew in November 1952. Holste later worked on other projects. If you are as good as gold, my reading friend, yours truly is ready to consider the possibility of pontificating on this machine, the MH-1521 Broussard, at a later date.

If I may be permitted a brief digression, the École de rééducation et de perfectionnement professionnels, closed at an indefinite date, possibly in 1940, was reborn from its ashes in February 1945. It moved a little later and became the Centre de formation professionnelle Bernard-Jugault, a name which commemorated Bernard Léon Louis Jugault, a member of the French resistance and communist CGT militant shot in August 1944 by the Germans. Yours truly unfortunately does not know what happened to this centre.

The pioneering institution which was the École de rééducation et de perfectionnement professionnels inspired the creation, in 1949, of the Association nationale interprofessionnelle pour la formation rationnelle de la main-d’œuvre, itself predecessor of today’s Agence nationale pour la formation personnelle des adultes, a name adopted in 1966, but let’s go back to our designer.

Would you believe that Holste was in Brazil in the mid-1960s? He then worked at the Instituto de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento, one of the elements of Centro Tećnico de Aeronáutica. Better yet, he contributed to the development of the IPD-6504 twin-engine commuter airliner. How was / is this aircraft tested in October 1968 and produced until 1991 (nearly 500 examples known as EMB-110 Bandeirante used by civilian and military operators in many countries) interesting, you ask?

Know that, in August 1969, the Brazilian government founded a state company, Empresa Brasileira de Aeronáutica Sociedade Anónima (Embraer). The Bandeirante was the first aircraft it produced, but certainly not the last, as we both know. The main rival of Bombardier Aéronautique, in terms of regional airliners, for many years, Embraer ultimately seems to have prevailed over this division of the Québec industrial giant Bombardier Incorporée which, as I type(d) these words, was about to withdraw from this type of production.

In fact, Bombardier sold the CRJ jet powered regional airliner program to Japanese industrial giant Mitsubishi Jidōsha Kōgyō Kabushiki Kaisha in June 2019. That same month, de Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited, a subsidiary of Longview Aviation Capital Corporation of Saanich, British Columbia, created for this purpose, acquired the type certificates for all versions of the Dash 8 turboprop regional airliner. The last examples of these 2 aircraft could leave the factory in 2020. As we both know, Airbus Group Naamloze Vennootschap acquired 50.1% of the production program of the CSeries medium range jet-powered airliner, immediately renamed Airbus A220, in October 2017. This aircraft is expected to remain in production for several years.

It should be noted that de Havilland Aircraft of Canada had / has nothing to do with de Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited, an aircraft manufacturer founded in 1928 known worldwide for its products, which went / go from the DHC-1 Chipmunk basic training aircraft to the aforementioned Dash 8, as well as the equally aforementioned Beaver, the DHC-3 Otter, the DHC-4 Caribou, the DHC-5 Buffalo, the DHC-6 Twin Otter and the Dash 7. Would you believe that the extraordinary collection of the aforementioned Canada Aviation and Space Museum includes examples of the Chipmunk, the Beaver (prototype), the Otter, the Twin Otter (prototype) and the Dash 7 (prototype)?

I have the sad duty to inform you that Holste left this world in August 1998, at the age of 84, forgotten by all.

Be well, my reading friend. Be well.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)