A milky way from Northern Ireland to England

Greetings to you, my reading friend. It is with some trepidation that I offer you the following story of hardship and, sadly enough, tragedy. This being said (typed?), this story was also one in which brave crews did all they could to help their fellow human beings. As such, it was and is well worth telling. Having put before you these words of warning, yours truly will now set the stage for our topic of the week, found in the 7 October 1948 issue of Photo-Journal, a weekly newspaper published in Montréal, Québec.

While it was true that the United Kingdom was one of the main contributors to the Allied victory in the Second World War, the sad fact was that, by 1945, this great power was but a shadow of its prewar self. Unlike Canada and the United States, which were economically better off after the conflict than before it, the United Kingdom was pretty well bankrupt. As a result, the government was forced to keep food rationing in force until July 1954. A bad summer drought in 1947, coming on top of the terrible winter of 1946-47, hit the British people hard. So little fresh milk reached certain parts of England that local people often failed to obtain the meagre ration (about 1.4 litre/ 2.5 Imperial pints / about 3 American pints per week per person) allocated to them by the government. Worse still, the absence of refrigerated trucks and near total absence of home refrigerators meant that any milk that arrived would go bad within a couple of days.

Faced with this situation, the Ministry of Food decided upon a bold course of action, in cooperation with the Ministry of Agriculture of Northern Ireland, where there was milk aplenty. One of the larger British independent / privately-owned airlines, Skyways Limited, received a contract to transport milk by air, from Belfast, Northern Ireland, to Liverpool, England, for distribution in northwest England. The company’s 3 Avro Lancastrians, a civilian version of the famous Lancaster heavy night bomber, were to make 4 roundtrips a day with more than one hundred 45 litre (10 Imperial gallons / 12 American gallons) churns on board. The absence of mechanised loading system meant that each of these churns had to be loaded and unloaded by hand – a perfect example of backbreaking work if there was one. All in all, Skyways was to transport about 63 650 litres (14 000 Imperial gallons / about 16 800 American gallons) of milk per day. And yes, the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa, Ontario, does include a Canadian-made Lancaster.

The experimental scheme, which began in August 1947, rarely met its daily target. Bad weather often prevented Skyways’ crews from flying. Worse still, a Lancastrian crashed on take off in Northern Ireland in early October. One of the 3 crew members suffered a broken ankle. The 1947 milk airlift came to a close in early November. The already bad weather kept getting worse as winter approached and the drought in England was itself coming to a close. Even though the 1947 milk airlift proved to be a partial success, the people and departments involved had learned a lot. And yes, each litre / gallon of milk was sold to consumers at a loss.

Sadly enough, a shortage of milk affected certain parts of England during the summer of 1948. As a result, the Ministry of Food had to institute a second airlift. This 1948 scheme was much larger and better organised than its predecessor. No less than 13 airplanes provided by 7 independent airlines flew between Northern Ireland (Belfast) and England (Blackpool and Liverpool), for example. Another operator leased an airplane to one of the airlines involved. Nine of the 14 airplanes involved in said airlift were large 4-engined machines able to carry 110 churns. The other 5 were smaller airplanes, Douglas DC-3s if you must know, able to carry 56 churns. And yes, the superb collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum includes a DC-3 and a very significant one at that. Incidentally, two of the large airplanes were Consolidated Liberators, another type found in the collection of this aforementioned national museum of Canada.

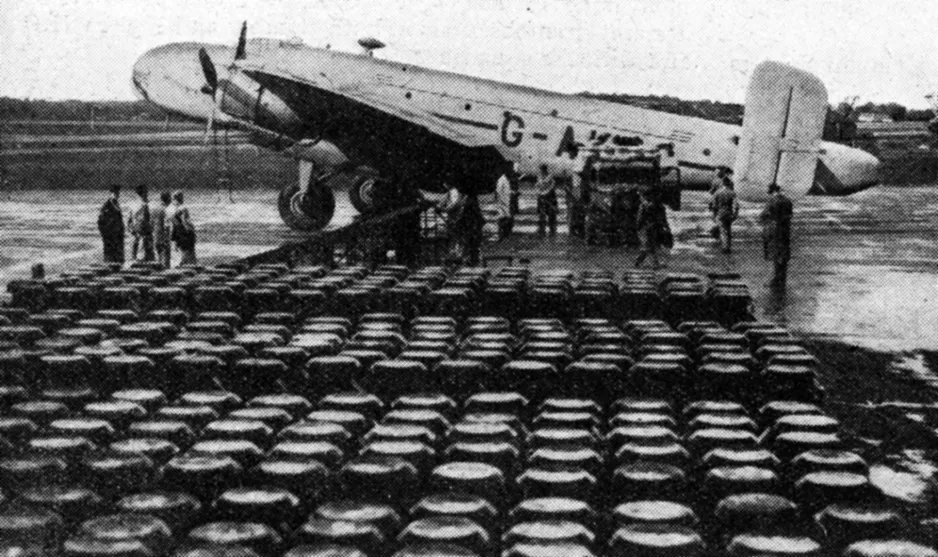

Another view of the Lancashire Aircraft Halifax transport plane we saw earlier. Many milk churns are visible in the foreground. Anon., “Here and there – Air float.” Flight, 9 September 1948, 290.

One of the airlines that took part in the airlift was, you guessed it, Lancashire Aircraft, the very company mentioned in the caption of the photo at the beginning of this article. Its contribution consisted of 2 Handley Page Halifax transport planes and … Yes, my knowledgeable reading friend, you are quite correct. Similar in appearance and capability to the aforementioned Lancaster, the Halifax is primarily known for its role as a heavy night bomber during the Second World War. This being said (typed?), one if not both of the Halifaxes provided by Lancashire Aircraft were ex-Royal Air Force transport planes.

Would you care to read a few words on the history of Lancashire Aircraft? No? Ahh, that’s too bad. This independent airline was a crown jewel of Eric Rylands Limited, a company owned by a civil aviation entrepreneur by the name of, you guessed it, Eric Rylands. Indeed, the aforementioned Skyways was acquired by Lancashire Aircraft in 1952. Interestingly enough, as certain subsidiaries of Eric Rylands ran out of aviation-related work (storing, scrapping, repairing, etc.), in the late 1940s, they began to produce bodies for used and brand new double-decker buses. You may be interested to read, or not, that a British independent airline, Silver City Airways Limited, acquired Lancashire Aircraft, in 1956. Another one, Euravia Limited, bought Skyways in 1962, but back to our story.

In order to ensure that the people in affected areas of England would receive their ration of milk, the Ministry of Food set the bar high. The crews of the 14 transport planes would have to complete 60 to 70 roundtrips a day in order to achieve their target of 227 500 litres (50 000 Imperial gallons / about 60 000 American gallons) of milk. For a brief time, the airport near Belfast was the busiest in the United Kingdom. Hoping to better manage this traffic, the British authorities installed a ground control approach radar at that airport and at the one near Liverpool. They also brought in additional air traffic controllers. It goes without saying that hundreds of men worked almost ceaselessly at Belfast, Blackpool and Liverpool to load and unload the heavy churns. And yes, each litre / gallon of milk was again sold to consumers at a loss.

The 1948 airlift began in late August. The Ministry of Food’s plan was to keep on flying until the end of October. While bad weather curtailed the number of flights on certain days, most of the milk needed by the people of England reached its destination. The success of the operation was marred by the death of the 4-man crew of an airplane on its way to England, in late September. Another airplane touched down short of a runway, in England, in mid October. Its crew seemingly walked away.

The airlift of 1948 came to a close in mid-October, earlier than expected. There were 2 main reasons for this. On the one hand, the milk shortage was no longer as critical. On the other, the transport planes were needed elsewhere – a point forcefully put forward by the British department of external / foreign / global affairs, the Foreign Office.

You see, my reading friend, back in early 1948, American, British and French governments secretly began to plan the creation of a state in the western half of Germany that they occupied. The Soviet government heard about this in March and was very displeased. When its former allies introduced a new currency in this western half of Germany, including the western part of Berlin, hoping to regain control of the economy, the Soviet government reacted by launching its own new currency in eastern Germany. It also closed all road, rail and canal access to the sectors of Berlin occupied by the United States, the United Kingdom and France.

Convinced of the need to stand fast, all 3 governments ordered their air forces to deliver the food and fuel that the population of West Berlin needed. The Berlin airlift began in June 1948, within days of the onset of the Soviet blockade. It continued until May 1949, when the Soviet government released its grip on the western half of the city. This blockade was one of the first major international crises of the post Second World War period. Worse still, tensions remained high after it ended. The Cold War was there to stay.

And no, the Royal Canadian Air Force did not take part in the Berlin airlift. The federal government chose not to become involved. This being said (typed?), some Canadian pilots did take part in the airlift.

On this, my reading friend, farewell, au revoir, auf wiedersehen and do svidaniya.

More Stories by

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)