‘It is all up to you!’ – The West Indian Domestic Scheme in Canada (1955–1967)

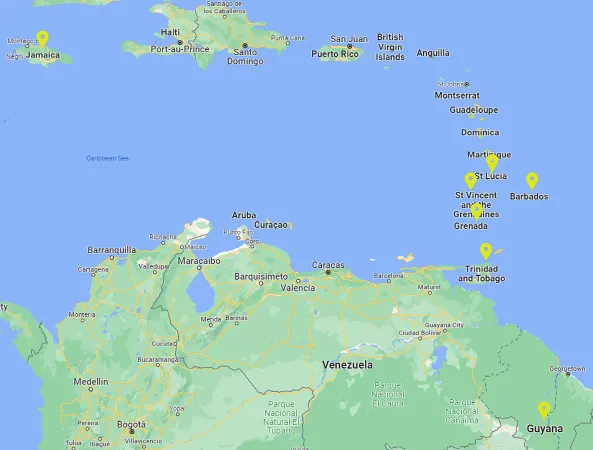

Click on map image to view larger version

Domestic labour refers to the essential work involved in maintaining a household, including cooking, cleaning, washing clothes, and caring for children and elders. The demand for domestic labour in Canada has often outpaced the supply of Canadian-born workers willing to participate in the field. As a response, the Canadian government has created various labour schemes to recruit women from Britain, America, Europe, and eventually, the Caribbean. From 1955 to 1967, the West Indian Domestic Scheme brought more than 3,000 Caribbean women, mostly from Jamaica, Barbados, Grenada, Guyana, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, St. Lucia, and Trinidad and Tobago, to perform domestic labour in Canada.

Domestic labour has long been devalued in Western culture as unskilled labour, and as a result, women who have been employed in the service have endured poor working conditions. These have included long working hours, low pay, and abuse by employers. Caribbean women emigrating as part of the West Indian Domestic Scheme faced very similar experiences, the severity of which would be influenced by their race, class, gender, and citizenship status.

This handbook given to women participating in the scheme informed them of the importance of the scheme and their intended roles and duties in Canada.

Domestic Labour Schemes in Canada

The first labour scheme for domestic workers targeted white British women in the late 19th century. Many Canadian-born women refused to enter the field because of poor working conditions, even if that meant taking lower paying jobs in more traditional fields. Rather than improve working conditions, the government decided to initiate a labour scheme. At the time, British women were the most preferred immigrants as they were considered for their potential roles as future wives and mothers of the nation (Arat-Koc, 1997). As British immigration was eventually unable to fill the labour demand as labour pools became exhausted, the government looked to other countries as sources for domestic labour.

A precursor to the West Indian Domestic Scheme occurred in 1911 when 100 women from Guadeloupe were recruited to work in Québec. The scheme was quickly cancelled by the government, mostly due to racist public outcry about the supposed physical and moral unsuitability of the women (Arat-Koc, 1997). During the recession of 1913 to 1915, and as Canadians were willing to take any work, the government deported many Caribbean domestic workers for fear that they would become dependent on government assistance.

Immigration of Caribbean domestic workers in Canada did not resume until 1955. By then, the Canadian government had been approached several times by Caribbean countries which saw labour schemes as a way to manage high levels of unemployment and underdevelopment. In Canada, demand for domestic workers increased as more white women entered the workforce outside of the home, and as European labour pools became exhausted. Canada saw the scheme as a way to fill the need for domestic labour and improve trade relations in the Caribbean. Unlike previous schemes, the West Indian Domestic Scheme was structured so that Caribbean countries took over the responsibility and cost of recruiting, training, medically testing, and transporting workers.

To qualify, women had to be unmarried, between the ages of 18 and 35, and have an 8th grade education. The women were granted permanent residency status and required to work for a period of one year before they were able to leave domestic service.

Advice to West Indian Women Recruited for Work in Canada as Household Helps

1. History of the Scheme

(a) You probably know that since 1955 the Canadian government has granted to certain territories in the West Indies a yearly quota to admit West Indian women to Canada as household helps.

(b) The continuation of this scheme has been due mainly to the good conduct and efficient service of the West Indian household helps who were sent to Canada in past years.

(c) You have a wonderful opportunity ahead, but you also have the responsibility to make good, so that in future years other West Indian women can look forward to similar opportunities. This is a comparatively new venture and you should regard yourself as missionaries who are resolved to succeed in order to help both.

Experiences in Canada

The women who participated in the scheme faced pressure from their home countries to guarantee the future success of the scheme. Women were given handbooks that provided advice on health and safety, proper attire, cultural differences, conditions of employment, proper conduct, and even personal cleanliness and grooming. They were expected to be courteous, polite, obedient, and perform duties cheerfully and efficiently.

The docility and subservience required of these women were not new ideas about Black women’s behaviour. Prior to abolition in Canada, enslaved and free Black women were most often charged with the domestic duties in the households of their enslavers and employers. Black women were believed to be naturally suited to domestic service and many Canadian born Black women were restricted to domestic service because of anti-Black racism in the workforce (Johnson, 2022 ; Maynard, 2017).

Many women who participated in the West Indian Domestic Scheme were highly educated and came to Canada for a variety of reasons, including furthering their education, seeing the world, and escaping poverty. However, their dreams of Canada did not always match their reality once they arrived. Most women arrived alone and struggled to find community or adapt to Canadian society. This was especially true for those who worked with families in cities and towns with little to no Black population. Some women were lucky to have employers who helped them navigate Canadian society and provided good working conditions while others exploited the women’s vulnerable position.

Some participants worked long hours, were intentionally underpaid, forced to share rooms with children or pets, and dealt with a high level of scrutiny and surveillance from their employers. In some cases, women were called racist slurs and experienced sexual abuse. Women feared deportation if they reported their working conditions, and some were kept intentionally misinformed about their rights by their employers. Many who left domestic service at the end of their contract experienced racial discrimination in their new career fields and in Canadian society more widely.

To help deal with isolation and loneliness, women joined churches and social groups to build community and access resources. For those who had their own rooms, small electronics like televisions and radios provided solace and entertainment. For example, saving up for a low-cost transistor radio like the one seen below offered an escape for some.

Example of a transistor radio that could have been purchased by women participating in the scheme. Thousands of transistor radios, like this one manufactured by Electra in Hong Kong, flooded Canadian markets in the 1960s to the 1980s. This radio includes a head phone jack for private listening and is easily portable with the leather case.

Conclusion

In 1967 the Canadian government introduced a points-based immigration scheme and ended the West Indian Domestic Scheme. The new system emphasized the demand for highly educated and skilled immigrants. Under the new system many domestic workers were unable to qualify as independent immigrants because domestic labour is considered unskilled. Rather than taking steps to improve the working conditions of domestic workers the government stopped granting permanent residency to many domestic workers from the region and instead issued temporary visas.

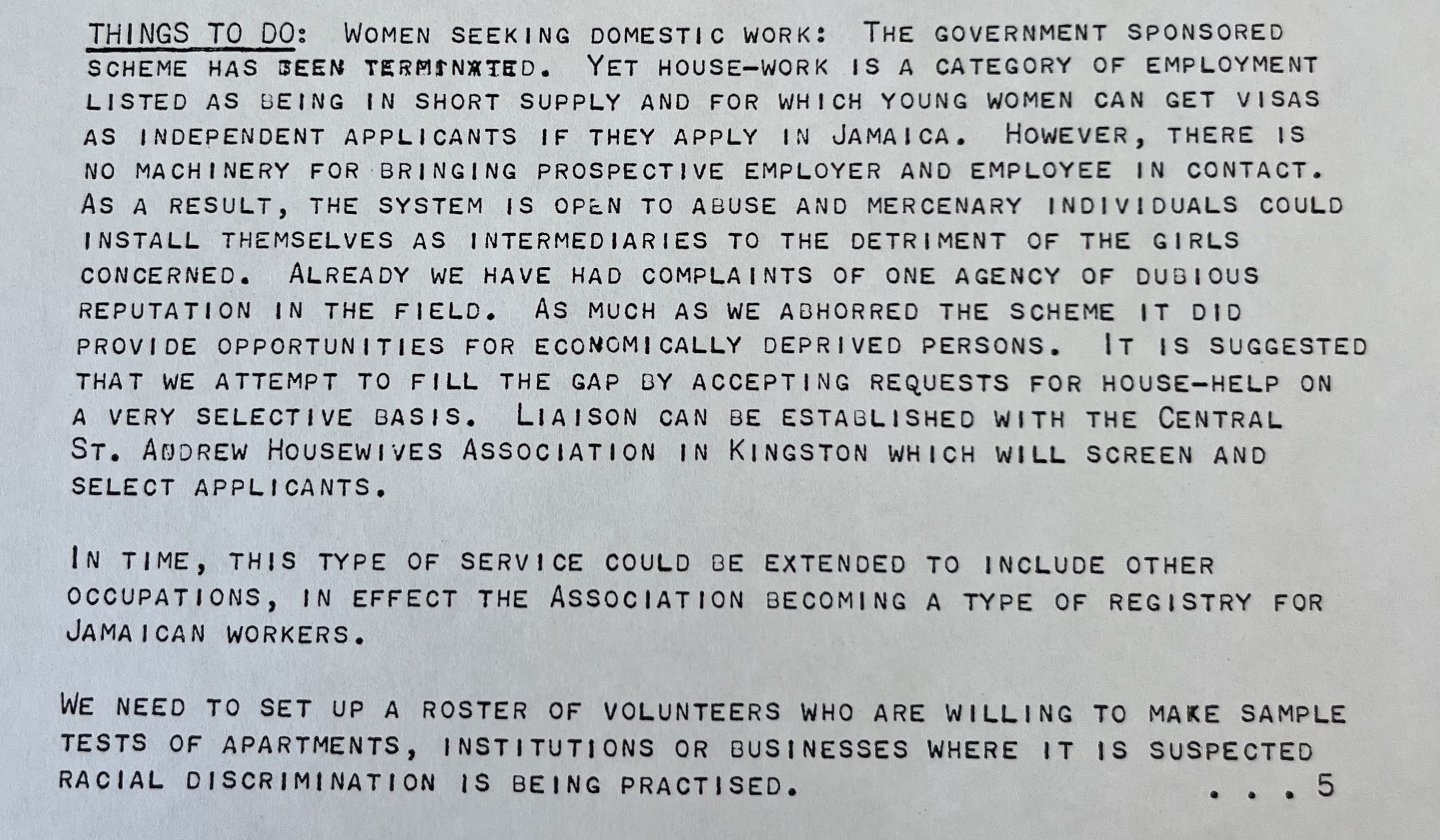

The Jamaican Canadian Association (JCA) 1968 Annual Report was given to members of the association to provide them with organizational updates and important community news. This excerpt from the report written by the president provides some insight into how the association understood the West Indian Domestic Scheme and the concerns that arose after it officially ended in 1968. The JCA continues to provide support and resources to members of the Jamaican community in Canada.

Document reads:

Things to do: Women seeking domestic work: The government sponsored scheme has been terminated. Yet house-work is a category of employment listed as being in short supply and for which young women can get visas as independent applications if they apply in Jamaica. However, there is not machinery for bringing prospective employer and employee in contact. As a result, the system is open to abuse and mercenary individuals could install themselves as intermediaries to the detriment of the girls concerned. Already we have had complaints of one agency of dubious reputation in the field. As much as we abhorred the scheme it did provide opportunities for economically deprived persons. It is suggested that we attempt to fill the gap by accepting requests for house-help on a very selective basis. Liaison can be established with the central St. Andrew Housewives Association in Kingston which will screen and select applicants.

In time, this type of service could be extended to include other occupations, in effect the association becoming a type of registry for Jamaican workers.

We need to set up a roster of volunteers who are willing to make sample tests of apartments, institutions or businesses where it is suspected racial discrimination is being practised.

Women who were a part of the West Indian Domestic Scheme helped facilitate the emigration of an entire generation of Black people to Canada. Many who left the field continued to support incoming domestic workers and fight for domestic workers rights. For example, Florence Robinson who arrived in Ottawa in the 1950s turned her home into a welcoming space for new community members, and Jean Augustine from Grenada became the first Black woman elected to the House of Commons. Many women helped with the creation and growth of several organizations that provided community, resources, and advocacy for domestic workers, including the Negro Citizenship Association, the Jamaican Canadian Association, and Domestic Workers United.

Additional Resources:

Arat-Koc, Sedef. “From ‘Mothers of the Nation’ to Migrant Workers.” In Not One of the Family :

Foreign Domestic Workers in Canada. Edited by Abigail B. (Abigail Bess) Bakan and

Daiva K. Stasiulis. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997.

Blackett, Adele. Everyday Transgressions: Domestic Workers’ Challenge to

International Labour Law. Cornell University Press, 2019.

Capital Heritage Oral History Project with West Indian Domestic Scheme participants:

Johnson, Michele A. ““...not likely to do well or to be an asset to this country”: Canadian

Restrictions of Black Caribbean Female Domestic Workers, 1910-1955.” In Unsettling

the Great White North. Edited by Michele A. Johnson and Funké Aladejebi. Toronto:

University of Toronto Press (2022): 280-309.

Maynard, Robyn. Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present.

Black Point: Fernwood Publishing, 2017.

Silvera, Makeda. Silenced: Caribbean Domestic Workers Talk With Makeda Silvera. Toronto:

Sister Vision Press, 1983.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!